Ulysses Grant hadn’t expected the presidency to be easy, but he didn’t think it would be this hard. He thought the hard work of forging peace with the South had been finished at Appomattox—that the generous terms he accorded General Robert E. Lee would start the nation’s healing process. But things hadn’t turned out that way. His great fear, during the final weeks of the war, had been that the Confederates would take to the hills and wage an unending guerrilla battle for their cause. It hadn’t happened then, to his considerable relief. But it was happening now.

Letters Grant received from the South soon after he took office in 1869 made the urgency of the situation clear. Robert Burns of Lexington, Ky., expressed doubt that the war was really over: “I write you to know if there is a law in this free land of ours that will protect and guarantee safety against the Rebel prowlers that infest every nook and corner, better known as K.K.K’s, who are armed and ready to take the life of any one if they do not endorse treason and rebellion.” Robert Scott, the Republican governor of South Carolina, declared the situation there beyond control. “The outrages in Spartanburg and Union Counties in this state have become so numerous, and such a reign of terror exists, that but few Republicans dare sleep in their houses at night. A number of people have been whipped and murdered.” Mrs. S.E. Lane of Chesterfield District, S.C., echoed Scott’s concerns: “Sir, we are in terror from Ku-Klux threats and outrages. There is neither law or justice in our midst. Our nearest neighbor, a prominent Republican, now lies dead, murdered by a disguised Ruffian Band, which attacked his house at midnight a few nights since. His wife also was murdered. She was buried yesterday, and a daughter is lying dangerously ill from a shot wound.”

Grant knew he must act. He also knew that he would be castigated no matter what he did. The Democrats would delight in any excuse to attack him. Many of his fellow Republicans were losing the conviction that had carried the Union to victory, and they wanted to wash their hands of the responsibility for ensuring former slaves enjoyed the rights promised them under the recently ratified 14th Amendment to the Constitution. Grant remembered the lonely moments before great battles, when everything rested on him. He recalled his mistakes—the surprise at Shiloh, the final charge at Cold Harbor—and knew that his judgment wasn’t perfect. But his instinct had always been to fight. And he prepared to fight now.

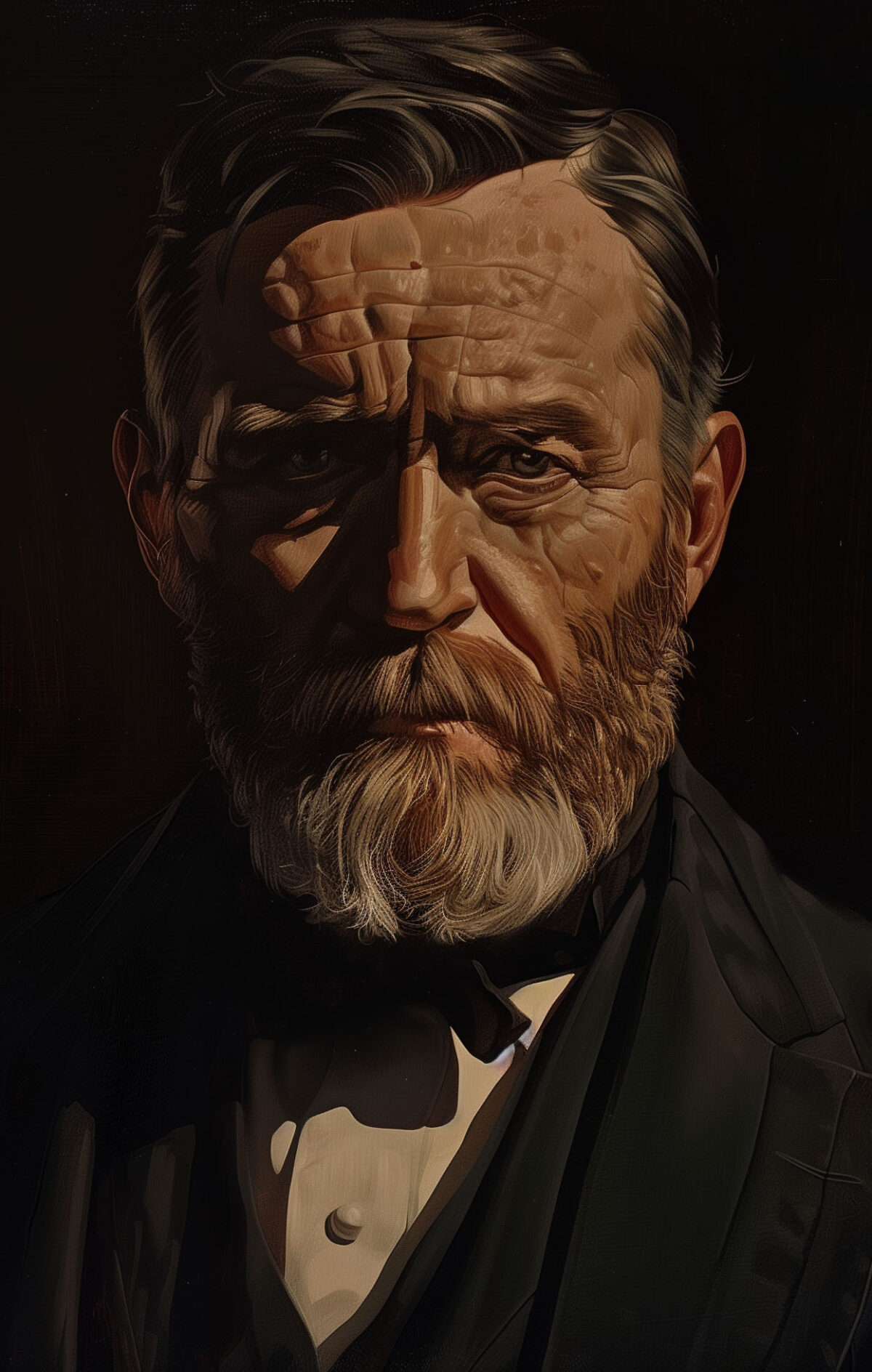

Historians have long underrated Grant’s performance as president. His administration was marred by scandals involving corrupt appointees and by an unstable economy that crashed in the Panic of 1873. Yet he deserves credit—and indeed respect—for the bold action he took at a perilous juncture in postwar Reconstruction to expand federal guarantees of racial equality and to protect freed slaves and their supporters from the terrorism of the Ku Klux Klan. Grant’s efforts to set things right in the South required moral resolve and considerable courage. It would be nearly a century before any other president demonstrated a similar commitment to civil rights.

Grant inherited an ugly mess from his immediate predecessor in the White House. Andrew Johnson, a Tennessee Democrat, had been added to Abraham Lincoln’s Republican reelection ticket in 1864, when Lincoln was desperate to keep war-weary Democrats from voting for George McClellan and a negotiated settlement with the South. When Johnson took office following Lincoln’s assassination, he publicly promised stern treatment of former Rebels but instead quietly curried the favor of his fellow Southern Democrats. He granted amnesty liberally, and soon the same people who had dominated Southern politics before the war did so again.

Grant was general of the Army of the United States during Johnson’s administration—and, not incidentally, the most popular man in the country. He wanted to be loyal to his commander in chief and supported the pardons of Southern leaders and the readmission of Confederate states to the Union. He even suffered through a blatant ploy to co-opt his popularity, reluctantly accompanying Johnson on a speaking tour aimed at bolstering public support for the president’s Reconstruction policies. But his sympathies were with the Republicans, who were appalled to see Southern lawmakers writing new “black codes” that reproduced slavery in all but name. Grant, with help from Congress, thwarted Johnson’s attempt to dump Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, a controversy that would prompt the Republicans’ Radical wing to wrest control of Reconstruction from the president, block the readmission of Southern states to the Union, impose military rule in the former Confederacy and impeach Johnson.

“Let us have peace,” Grant said on accepting the Republican nomination for president in 1868. And he emphasized peace once in office. But not peace at any price: He insisted that the South recognize the old ways were dead. Former slaves must be accepted as citizens and accorded the rights of citizens. Anything less would dishonor the memory of those many thousands who had died in the cause of Union and freedom.

Many in the South, however, held firm to the opposite viewpoint. They were virulently opposed to the idea of equal rights for blacks. The Ku Klux Klan was born in Tennessee in 1866 as a fraternal organization of Confederate veterans, but it quickly evolved from men telling war stories to men making terroristic night rides, as its members sought to enforce white supremacy and prevent the freedmen and their white Republican allies from voting or otherwise participating in the democratic process. Grant loathed the Klan for its murderous tactics and its revival of the secessionist spirit. The Klansmen seemed bent on provoking a new civil war. Yet they were nearly impossible to prosecute under existing laws. They terrorized the few state officials who might have brought charges against them, and federal law didn’t cover most local outbreaks of violence.

The only answer, Grant judged, was new federal authority. In 1871 he asked Congress to write a law allowing him to deal with the Klansmen. “A condition of affairs now exists in some of the States of the Union rendering life and property insecure and the carrying of the mails and the collection of the revenue dangerous,” he told the legislators. The reference to the mails and revenue was shrewd: Being patently within the purview of the federal government, they provided constitutional cover for action. Grant noted that “the power to correct these evils is beyond the control of the State authorities,” but it wasn’t clear, he added, that the president had power, within the limits of existing laws, to deal with emergencies like this.

So he made a pitch for extraordinary powers, embodied in a bill that would allow him to suspend habeas corpus in sections of the South. “I urgently recommend such legislation as in the judgment of Congress shall effectually secure life, liberty, and property and the enforcement of law in all parts of the United States,” he said.

Grant’s request sparked outrage from Democrats, who called it the most repugnant form of partisanship. “Many of you would rather see the President dictator today than to see the Democratic party come into power,” bellowed James Beck, a Democratic congressman from Kentucky. Beck noted that some Republicans were grumbling, for reasons of their own. “I do not know that General Grant is as bad a man as some of his leading party friends say he is,” Beck twitted. “They know him better than I. But if he was the best man on earth, if he was General Washington himself, the power this bill proposes to give should not be conferred on him.” Fernando Wood of New York reiterated the dictatorial theme. “In no portion of our history has any such power been delegated,” Wood said. “In no free government anywhere in the world has any such power been delegated by the people. Nor is there any despot for the past century who would attempt to exercise it.”

Some Republicans stood by Grant. John Hawley of Illinois, a state that claimed Grant as a favorite son, called the charges of dictatorship ludicrous. “Sir, why shall we say this great chieftain, who marched at the head of more than a million men, will seek for a pretext to call out the militia in one or two or more states in order to subvert the liberties of the American people, when we know there was a day when he stood at the head of an army composed of a million veteran soldiers, and yet at the behest of the civil power this great army melted away like the dew before the morning sun?”

Still, other Republicans were uneasy. “I do not think that Congress ought to take the initiative in thrusting upon the Executive more tools when there is no evidence from him that he needs them,” James Garfield of Ohio wrote to Jacob Cox, Grant’s former interior secretary. Garfield was unmoved by the tales of violence against Southern blacks and Republicans, which he considered exaggerated. And he feared that the extraordinary powers requested by Grant would indeed make him an autocrat or something close, saying: “It seems to me that this will virtually empower the President to abolish state governments.” Garfield also thought the move would ruin the Republican Party.

Yet Grant held his party together sufficiently to get his bill, and in April 1871 Congress approved what was formally named “An Act to Enforce the Provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment” but informally dubbed the Ku Klux Klan Act. The measure allowed persons deprived of their rights under the Constitution to bring suit in federal courts (rather than state courts). It defined conspiracy to deprive citizens of the equal protection of the laws or prevent citizens from voting, and it permitted the prosecution of such conspiracies in federal courts. It also declared that when the denial of rights was so organized and egregious that it overawed state authorities, or when state authorities connived in the denial, such combinations “shall be deemed a rebellion against the government of the United States.” The president was then authorized “to suspend the privileges of the writ of habeas corpus, to the end that such rebellion may be overthrown.”

The law gave Grant the power he sought, but it was up to him to use it. “It is my earnest wish that peace and cheerful obedience to law may prevail throughout the land and that all traces of our late unhappy civil strife may be speedily removed,” the president proclaimed after its passage. Yet neither Grant’s words nor the legislation did anything to sway Southern racists.

Within days came more pleas from Southern blacks and Republicans for presidential protection. “There is a Ku Klux organization in this county, who have recently closed a colored school and are now taking steps to close others,” the editor of a paper called Equal Rights wrote from Pontotoc, Miss. “I am threatened with personal violence.” The town was an outpost of loyalty to the Union, but Republicans there were at grave danger from Democrats evidently determined to avenge the defeat of the rebellion. “All the hopes of the loyal people are fixed on you,” the editor wrote. Two weeks later, another desperate message arrived from Pontotoc. “The Ku Klux attacked us Friday night,” two survivors of an assault telegraphed. “They threaten to return and burn the town. Can we have troops?”

Grant shifted some troops from Kentucky to Mississippi, but he focused his attention on South Carolina. The Palmetto State had special significance, since it had been the first to secede and the first to fire on Union forces. It was also the epicenter of Klan activity in the early 1870s. Grant sent Amos Akerman, the attorney general, to South Carolina to document the depredations there; upon receiving Akerman’s report, he ordered those responsible to disperse, retire to their homes and surrender “all arms, ammunition, uniforms, disguises and other means and implements” used in the unlawful violence. He gave them five days.

The Klansmen ignored him, as Grant expected they would. So in October 1871, he cracked down. Employing his special powers, he suspended habeas corpus in nine counties of South Carolina most seriously affected by Klan violence and sent in federal marshals and federal troops. The purpose of the habeas suspension was to let the marshals and troops round up suspected terrorists without concern about producing legal justification before a judge. Several hundred marauders were quickly arrested while other suspects fled the counties and the state to avoid detention. The assault disrupted Klan networks and instilled the fear of federal power in many South Carolinians who had supplied tacit support to the organization. The sweep stopped the civil unrest and demonstrated the resolve of the federal government to defend the rights of the freedmen.

The trials, months later, proved anticlimactic. Akerman accepted plea bargains from many defendants in exchange for information that further undermined the Klan. Mostly moderate sentences were handed down—sometimes by black-majority juries. But the Klan had been crippled. Political violence in South Carolina and across the South declined dramatically, and soon the KKK virtually disappeared from Southern life, not to be seen again until the 20th century, when it would rear up in the South and other parts of the country. “The law on the side of freedom is of great advantage only where there is power to make that law respected,” observed Frederick Douglass, the former slave and abolitionist. Grant had acquired and exercised the necessary power, and had compelled rebel resisters to respect the law.

Yet in doing so he won few friends. The Democrats assailed him more vehemently than ever, and a whole wing of Republicans who wanted to let the freedmen fend for themselves abandoned Grant for a new party, the Liberal Republicans, ahead of the 1872 election.

Grant never repented, even as he appreciated that his bold stroke couldn’t be repeated. The Klan had been crushed, but the majority of Southern whites remained unreconciled to black equality, and their views couldn’t be ignored indefinitely without irreparable damage to democracy. Grant couldn’t hold the line for equality by himself.

During the following years and decades, the line gradually gave way. In one state after another, the white majorities reclaimed political control and, by less violent means than the Klan had employed, disenfranchised the freedmen. Not until Lyndon Johnson occupied the White House in the 1960s would another U.S. president push for black equality.

Those for whom Grant fought didn’t forget him. When Grant died, African-American churches across the country prayed for his soul. A group of black Union veterans wished him Godspeed on his final journey. “In General Grant’s death,” they resolved, “the colored people of this and all other countries, and the oppressed everywhere, irrespective of complexion, have lost a preeminently true and faithful defender.”

H.W. Brands’ current book is The Man Who Saved the Union: Ulysses Grant in War and Peace.

Originally published in the December 2012 issue of American History. To subscribe, click here.