Korean War ace Robbie Risner emerged as a POW leader during the seven years he spent in North Vietnam’s infamous Hanoi Hilton.

James Robinson “Robbie” Risner, whose military career spanned more than 30 years, was among the most remarkable pilots of his generation. His flying exploits were notable for both triumphs and bitter tragedies.

Born in 1925, Risner enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Forces in 1943 and earned his wings in 1944. He trained on several aircraft early in his career, including the P-38 Lightning, P-39 Airacobra and P-40 Warhawk. During World War II he was assigned to the 30th Fighter Squadron, based in Panama. The posting was a disappointment for Risner, who very much wanted to get into combat. His time in Panama was marked by extensive flying and hell-raising, in about equal measures. Following the war, Risner pursued a variety of jobs, including working as an auto mechanic and running a gas station, none of which he liked.

Eager to return to the air, Risner joined the Oklahoma Air National Guard. He trained on the F-51 Mustang and flew regularly, though not always on authorized missions. On one notable occasion, Risner took off in an F-51 for Padre Island, Texas, on the Gulf Coast to acquire copious quantities of shrimp for a party. During the flight he ran into foul weather and flew above the clouds, navigating by dead reckoning. But when he descended, he realized he had miscalculated his position and was lost. Landing on a dry lakebed, he endured a night spent under his parachute, battered by a hurricane.

The next day Risner discovered that he had landed in Mexico. After hitching a ride to Tampico, he informed officials at the U.S. embassy that an American warplane was sitting in foreign territory. Upon returning to the U.S. Risner was reprimanded for the flight and learned that his wife Kathleen had miscarried during his time out of the country (they would go on to have five boys).

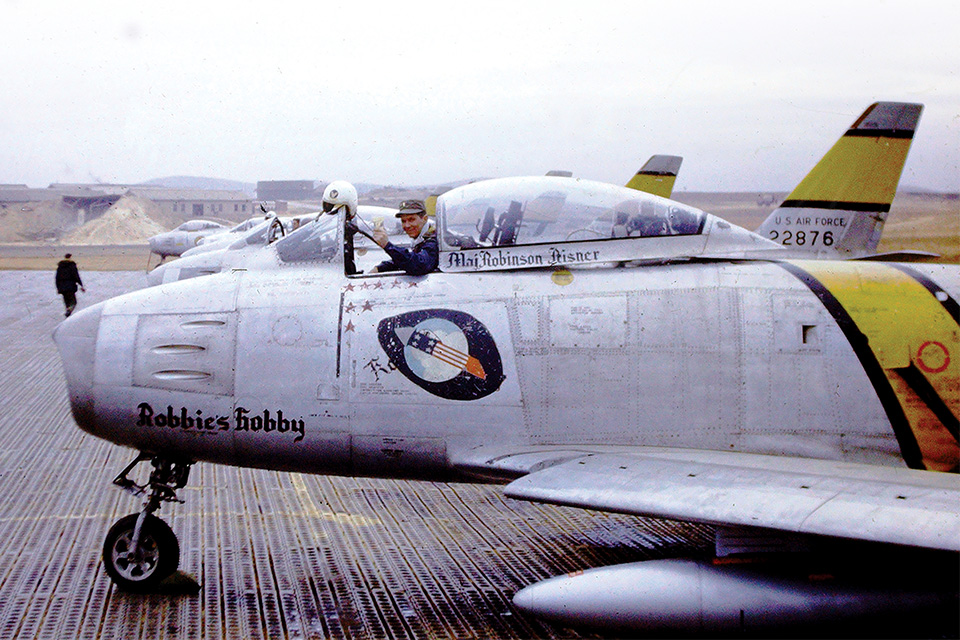

Risner’s life took a dramatic turn when he was recalled to active duty early in 1951. He transitioned to flying jets, including the F-80 Shooting Star and, in Korea, the F-86 Sabre. So strong was his desire to be assigned to a combat squadron that, in a move reminiscent of Chuck Yeager hiding his broken ribs so he could take the Bell X-1 supersonic, Risner concealed a broken hand (incurred falling from a horse, also like Yeager) lest he be disqualified.

While in Korea, Risner shot down eight MiG-15s, becoming the 20th American jet ace. His Korea War service is most widely remembered for two incidents that occurred during the same mission on September 15, 1952. Risner and wingman Joe Logan were flying F-86s in MiG Alley—along the Yalu River near the airstrip at Antung, China—on a mission escorting F-84 Thunderjet fighter-bombers. During the flight Risner fought a MiG in a wild, twisting, low-level chase, shooting off its canopy before sending it down in flames. The MiG crashed into a line of other MiGs parked on the airstrip, destroying them. “You just took out the whole Chinese air force!” Logan called out.

On that mission, Logan’s Sabre was struck by groundfire, badly damaged and rapidly leaking fuel. Fearing that his wingman would have to eject over enemy territory, Risner came up with a novel idea: He instructed Logan to shut down his engine and inserted the nose of his own F-86 into Logan’s tailpipe. Risner hoped to push Logan as close as possible to American-held Cho-do Island, where he could eject and be rescued by Air Force personnel.

Risner’s scheme worked, though his canopy became coated with fuel and oil leaking from Logan’s plane, seriously compromising his visibility. The jets also had to constantly reconnect due to turbulence. As they approached Cho-do, Risner pulled away and Logan radioed, “I’ll see you at the base tonight.” Logan ejected near the shore, but during the helicopter rescue he became entangled in his parachute cords and drowned. Risner met the rescue helicopter when it landed, but there was nobody to greet.

More than a decade later, Risner was a squadron commander flying the F-105 Thunderchief in Vietnam. He led missions during the Rolling Thunder bombing campaign and also personally took part in some of the famous raids on the Thanh Hoa Bridge. On March 22, 1965, he was rescued after ejecting over the Gulf of Tonkin, but his luck would soon run out.

On September 16, during a so-called Iron Hand mission (targeting surface-to-air missile sites), Risner’s “Thud” was damaged by groundfire, and he was again forced to eject. This time Risner was captured in short order by enemy troops and imprisoned at the dreaded Hoa Lo Prison, known as the “Hanoi Hilton.” He was interrogated and tortured, ultimately spending seven years as a prisoner of war—three of them in solitary confinement.

Risner and U.S. Navy Commander James Stockdale were widely credited by the POWs for their inspirational leadership. Risner advised the men to “resist until you are tortured but do not take torture to the point where you lose the permanent use of your limbs.” He prayed frequently during his captivity, later crediting it with helping him get through the ordeal. Released in February 1973, he learned that his brother and mother had both died during his captivity. Regarding anti-war protesters, Risner said: “I was very resentful at first. However, I soon realized that these people were using the very freedom for which I had been fighting. So, I really have no criticism.” He soon returned to the cockpit, becoming proficient in flying the F-4 Phantom. Risner retired from the Air Force in 1976 and died in 2013 following a stroke.

In his honor, a nine-foot-tall statue of Risner stands on the U.S. Air Force Academy grounds in Colorado Springs. The height is symbolic and refers to Risner’s response on hearing his men in the Hanoi Hilton singing the “Star-Spangled Banner” and “God Bless America” in defiance of their captors. Said Risner of the occasion, “I felt like I was nine feet tall and could go bear hunting with a switch.”

This article originally appeared in the July 2020 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here!