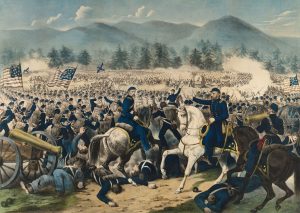

Although only minor National Park Service signage alerts you to the boundaries of the vast Gettysburg battlefield at its outer edges bleeding into neighboring counties, it’s almost impossible not to know by instinct when you’ve crossed the threshold onto its hallowed, historic ground. It just feels different. You have to wonder if the area’s residents feel the same. It’s little doubt those of 1863 felt it, too, as many bore the burden of the battle while it raged and, likely, for the rest of their lives after.

When the battle broke out in this county seat on July 1, 1863, college classes were interrupted, business stopped, and a bustling railroad town was stilled. If residents hadn’t fled for safety elsewhere, they shuttered themselves in basements and attics, biding their time in terror as the sounds of war erupted around them.

Of the battle’s first-day glimpse of what was to come, 15-year-old Tillie Pierce wrote in her now famously published diary, “Soon the booming of cannon was heard, then great clouds of smoke were seen rising beyond the ridge. The sound became louder and louder and was now incessant. The troops passing us moved faster, the men had now become excited and urged on their horses. The battle was waging. This was my first terrible experience.” It was not her last.

There are many ways to experience a visit to Gettysburg, and often a trip revolves around sites related to the fighting or the soldier stories and personalities popularized by modern culture. The civilian story is lesser told…but certainly not less engaging, or less poignant. The town’s homes and mainstays became lookouts, hideouts, and the command centers of the armies’ top generals. A tour of some of the most iconic spots on the battlefield today encompasses the civilian story, as do several museums and interpretive centers in town, many marked with Civil War Trails signs. It’s an experience you won’t forget.

Meade’s Headquarters

Taneytown Road and Hunt Ave.

Maj. Gen. George Meade made Lydia Leister’s simple frame home his headquarters, holding a council of war there the night of July 2 to decide if the army should stay to fight another day. The widow returned after the battle to find her food stores and two tons of hay gone; the wheat she had planted destroyed; and her barn siding removed for firewood and grave markers. Also gone were her horse and cow, and 17 dead Union horses scattered across her fields and near her spring had fouled the water, rendering it unusable. Despite the challenge ahead, she never backed down. By 1868, she had begun adding onto her modest property.

Seminary Ridge Museum and Education Center

61 Seminary Ridge

The Seminary Ridge Museum and Education Center is housed in the oldest building on the United Lutheran Seminary campus, where all study and worship came to an abrupt halt July 1, as troops from both sides occupied the building and its cupola (used as a lookout post by Brig. Gen. John Buford). Hundreds of wounded soldiers found themselves here, as it served as one of the largest field hospitals in Gettysburg until September 16, 1863. Classes resumed mere days later. For information on tours and programs, visit seminaryridgemuseum.org.

‘The Hero of Gettysburg’

Stone Avenue south ofChambersburg Road

No Gettysburg citizen story is more famous than that of John Burns. A War of 1812 veteran, the 70-year-old resident grabbed his musket and fought alongside Union soldiers west of town—and was wounded—on July 1. Those soldiers were forced to leave him behind, but he convinced Confederates he was a noncombatant after crawling away from his rifle and burying his ammunition. Soon a national celebrity, he would receive personal thanks from Abraham Lincoln, and Congress passed a special act granting him a pension. On July 1, 1903, a monument to Burns was dedicated on McPherson’s Ridge.

Train Depot

35 Carlisle St.

As the fighting raged, this bustling station was not immune to the burden of war. In fact, even before the battle began, Union General John Buford established a hospital here for his sick cavalrymen. Iron Brigade surgeon Jacob Ebersole served here, including for weeks after the battle while the hub facilitated the transport of relief supplies and removal of Federal dead and wounded. On November 18, 1863, an evening train chugged into town bringing President Abraham Lincoln, who delivered his Gettysburg Address the next day at the new national cemetery. Using immersive VR technology, the depot’s Ticket to the Past Museum allows visitors to journey back to 1863.

Shriver House and Museum

309 Baltimore Street

When Hettie Shriver and her children returned to their home in downtown Gettysburg on July 7, they found it had been used as a hospital and Confederates had set up a sharpshooter nest in the attic. All of the Shrivers’ food, clothing, blankets, linens, tools, and any “booty” such as money, silver, or liquor, had been confiscated. Five months after the Battle of Gettysburg, George Shriver was granted a four-day furlough giving him the opportunity to spend Christmas with Hettie and their daughters, Sadie and Mollie. He had been away from home for more than two years. In 1864, he was taken prisoner and sent to Andersonville Prison. He died in August of that year. The Shriver house and saloon have been restored and now operate as a museum, with several rooms depicting the tragic condition the Shrivers found their home in battle’s aftermath.

Beyond the Battle Museum

368 Springs Ave.

In April 2023, the Adams County Historical Society opened a new 29,000-square-foot complex just north of the Gettysburg battlefield, which showcases civilian accounts from the Battle of Gettysburg and Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. The Beyond the Battle Museum features some of Gettysburg’s rarest artifacts and uses media and special effects technology to take visitors on a journey through time. Caught in the Crossfire, a 360-degree re-creation of a home trapped between Union and Confederate lines, uses light projections, surround-sound speakers, and special effects to transport visitors back to the battle and the civilian experience. Guests enter a family’s home shortly after their rush to safety in the cellar below, hear their hushed conversations, split-second decisions, and life-or-death encounters with Union and Confederate troops.

The Cashtown Inn

1325 Old Rte. 30, Orrtanna

Built in 1797 as a stagecoach stop, the Inn served as temporary headquarters for many Confederate officers during the Gettysburg Campaign. Today, the Inn is still a bustling stop just west of Gettysburg hosting guests for overnight stays and special dinners.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2024 issue of America’s Civil War magazine.