It has been more than 50 years since the aircraft carrier USS Guadalcanal‘s hunter-killer group captured the German submarine U-505 off Cape Blanco in French West Africa, but for former crewman Hans Goebeler the memories are as fresh as ever. The 74-year-old retiree still bristles at any suggestion that U-505, the first ship captured on the high seas by the U.S. Navy since the War of 1812, was an unlucky ship.

‘There’s no reason to say that the U-505 was a hard-luck ship,’ says Goebeler. ‘No matter what happened to her, she always brought us back. She wouldn’t even let anything happen to the Americans who boarded her. Those other so-called lucky ships, well, you might have shaved with them yesterday because they are all scrap now. But U-505 is on display in Chicago [at the Museum of Science and Industry] as a monument to the boys on both sides who died in the war. I think our boat was the luckiest ship in World War II.’ Goebeler should know; more that 50 years ago, in the warm ocean waters off the West African coast, it was he who ‘pulled the plug’ to scuttle U-505 — the U-boat that wouldn’t die.

Goebeler was born in 1923 in the small Hessian farming community of Frankenburg, about 75 miles northeast of Frankfurt. His father was an official in the German Reichsbahn railway system and raised his son with a firm belief in the value of hard work, self-reliance and patriotism. ‘My father was a soldier in the First World War,’ Goebeler says. ‘He fought in the East but was captured by the Russians. He saw horrible, unspeakable things done by the Bolsheviks during the revolution. They did these things to their own people in the name of communism! I swore I would work to make Germany strong and to never let the Communists take over my country.’

Even as a youngster, Goebeler displayed the kind of abilities that the German navy required for its elite U-boat arm. He joined the Deutsches Jungvolk, the branch of the Hitler Youth organization for boys between the ages of 8 and 14. Exhibiting a precocious intelligence and charisma that still shines today, he quickly rose in rank to become the youngest DJ leader in the country. On rare occasions, Goebeler can be coaxed into showing his special Hitler Youth Leader identity booklet and an accompanying photograph showing him in uniform, surrounded by his much older and taller unit members.

Goebeler was 15 years old when Europe was plunged into World War II, and he immediately attempted to volunteer for the Germany navy. Rejected by the navy because of his youth and a mistaken diagnosis of colorblindness, he turned his energies toward schoolwork. Goebeler excelled in his studies, showing a special aptitude for mechanical engineering. By the time he was 17, he had earned a driver’s license and completed the four-year apprenticeship for master motor mechanic in half the usual time. Ten days after he received his master’s certificate, however, he was finally accepted by the German navy.

Although Goebeler and his fellow recruits did not realize it at the time, they were being very carefully watched and evaluated during basic training. To his immense pride and satisfaction, Goebeler learned that he had been chosen for service in the navy’s elite submarine corps. ‘At first our training was mostly infantry combat related,’ he remembers. ‘Later, we got transferred to submarine school and had to learn every valve and line in a submarine. I was already trained as a motor mechanic, but the navy made me take submarine electrician classes. That way, they got two for the price of one; I could work on either the diesel engines or the electric motors on a U-boat.’

Early in the war, new crewmen were usually sent from submarine school to the shipyards to watch the final construction of the submarines in which they would serve, in order to better familiarize themselves with the technical details. Goebeler’s mastery of the material, however, allowed him to be posted directly to an operational unit, the 2nd U-boat Flotilla, stationed in Lorient on France’s Atlantic coast.

U-505‘s keel was laid by the Deutsche Werft shipyard in Hamburg on June 12, 1940, just as French resistance was crumbling before the onslaught of Germany’s blitzkrieg. By the time she was completed in August of the next year, more than 8 million tons of Allied shipping had been sunk, and U-boats had replaced the Luftwaffe as the gravest threat to Britain’s survival. The situation in the Atlantic had reached such a critical stage that the United States, technically still neutral, was providing escort ships for Allied convoys to England; the escorts reported or attacked any U-boats they encountered. It was during this decisive phase of the war that U-505 was officially commissioned into the German navy on August 26, 1941.

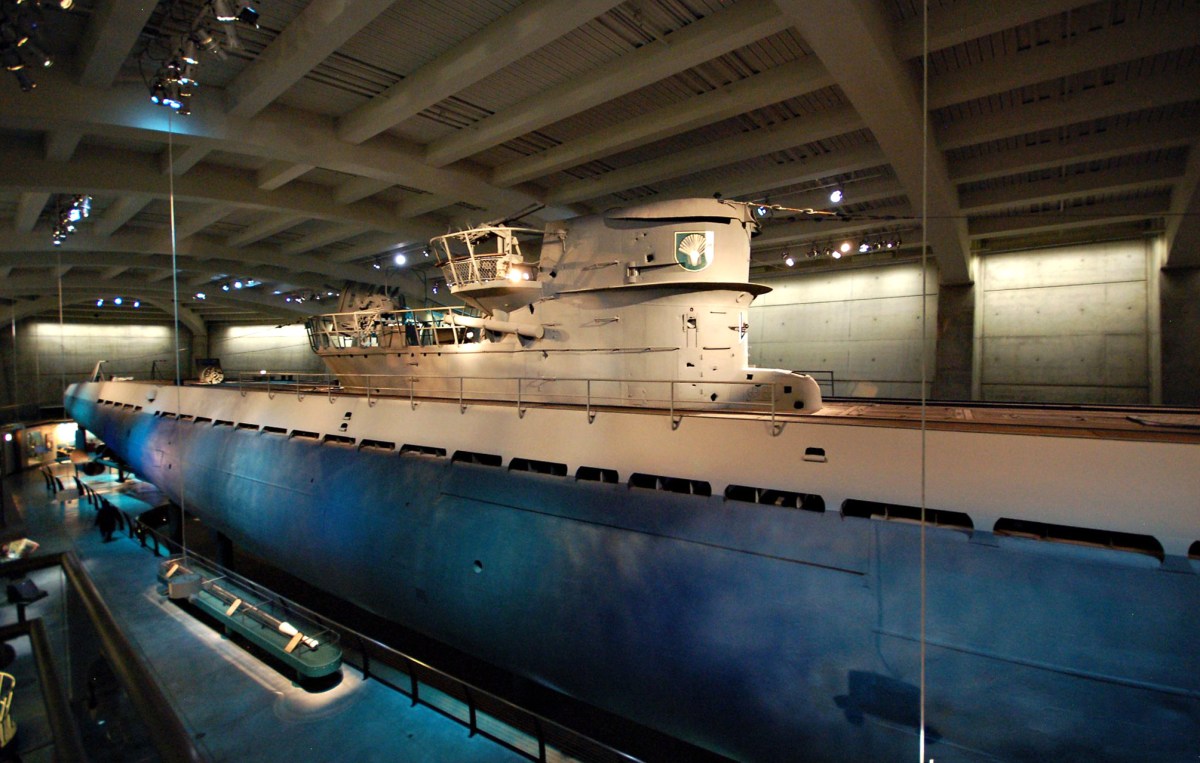

U-505 was a type IXc submarine, one of the larger, long-range boats that U-boat fleet commander Admiral Karl Donitz intended to use on the periphery of the Atlantic. More than 252 feet long and displacing 1,232 tons when fully loaded, she was designed to operate most of the time on the surface, diving only when necessary for attack or escape. Her battery-driven electric motors could propel her at only 7 knots while submerged, though her diesel engines could make over 18 knots on the surface. She was armed with a 105mm deck gun located forward of the conning tower and a maximum of 22 torpedoes. Later in the war, when Allied planes began making surface attacks on German submarines, with devastating effect, her deck gun was removed and replaced with anti-aircraft weapons.

The first commander assigned to U-505 was Captain Axel Loewe, a thoroughly trained professional whose self-assured manner inspired immediate trust and confidence in the green crew of four officers and 56 men. The captain’s name, which means ‘Lion’ in German, provided the inspiration for the first insignia of U-505 — a rampaging lion holding an ax. A large shield bearing the ship’s new emblem was proudly painted on both sides of the conning tower, symbolizing the imprint Loewe’s forceful personality would have on his crew.

By the end of November 1941, after several training and shakedown cruises in the Baltic Sea, U-505 and her crew passed their final operational readiness tests. Live torpedoes were loaded on board, and the sub was pronounced ready for deployment to the war zone.

U-505‘s first operational mission was its trip from the Kiel naval base to the submarine pens of the 2nd U-boat Flotilla at Lorient, France. Lorient, on the Bay of Biscay, was one of the primary sally ports for the German U-boats that were attempting to strangle England and prevent supplies from reaching her.

Following standard procedure, U-505 avoided the shorter but far more dangerous route from Kiel through the English Channel. She instead sailed north around Scotland and Ireland, then south and east to the Bay of Biscay. Although the boat encountered several British destroyers, extremely rough weather made it impossible for either side to launch an attack. Loewe had to content himself with spending the two-week cruise performing practice drills. By mid-February 1942, U-505 had been loaded with provisions and was ready to sail out of Lorient on her first real war patrol.

Goebeler arrived at Lorient two weeks before the boat. His original assignment was to U-105, but when a slot opened up on U-505, he eagerly accepted the reassignment. Reporting for duty in his brand-new uniform, Goebeler was surprised to learn that Loewe had selected him to be a control room operator rather than a mechanic, as he had been trained to be. ‘The Kapitän didn’t pay much attention to a person’s rank or education,’ Goebeler remembers. ‘On a U-boat you only cared about how well a man did his job. Some of the boys had even been in trouble with the police. But Loewe said: `Well, you’ve got to have brains and skills to get through tough situations. If they use those skills to keep my boat alive, I will be happy to have them!’ I was only a Machine Gefreiter [mechanic first class], but he assigned me to the control room of U-505 after we had a talk in his cabin.’

Although he had missed her maiden voyage, Goebeler accompanied U-505 on every subsequent war patrol she made, right up to the grand finale on June 4, 1944, when he would risk his life to sink his own ship.

Goebeler’s first war patrol not only severely tested his nerves but also sorely tested his physical endurance. Smaller and younger than most of his mates, Goebeler had to work twice as hard to match the performance of the more seasoned members of the crew. ‘I hadn’t gained my `sea legs’ yet and needed to adjust to seasickness,’ Goebeler explains. ‘On that first mission, we went through very heavy weather. But no matter how sick someone was, he had to do his duty without mistakes in the control room. Even if everything was rolling 30 degrees from side to side, he must do things perfectly, or he could sink the boat. In a way, I was lucky the weather was so heavy because when you start things the hard way, it’s easier for you later on. Even so, some men never adjusted. One petty officer returned to duty on destroyers because he never got used to the motions of a submarine.’

That first war patrol, which lasted from February 11 to May 7, 1942, took U-505 to the West African coast near Freetown. There she operated as a lone wolf, crisscrossing the sea lanes in search of ships supplying the Allied forces fighting Field Marshal Erwin Rommel in North Africa. At that time, the pickings were still easy for German submarines, and the crew of U-505 was eager to return to Lorient with a conning tower full of victory pennants, as an answer to the good-natured teasing they had received from veteran crews. They did not have to wait long. On the evening of May 5, they spotted the 6,000-ton British freighter Ben Mohr heading for Freetown without escort. Firing three torpedoes, U-505 made her first kill. Over the next few weeks, Loewe used his remaining torpedoes to send two more freighters and a tanker to the bottom of the sea, for a total of 26,000 tons sunk.

The patrol was not without its moments of danger for U-505. The submarine was constantly harassed by Allied aircraft and escort ships, and the crew endured several bombing and depth-charge attacks. At one point, a technical failure caused the relief valve on diving tank No. 7 to stick in the closed position. The resultant imbalance of weight caused the U-boat to float on the surface with its stern sticking up into the air at a 40-degree angle. The crew experienced several anxious moments before Loewe could get the boat on an even keel and dive to escape an approaching British Short Sunderland flying boat. Loewe’s handling of the incident impressed Goebeler. ‘This was one time when a Kapitän would have been justified for yelling, but he remained cool and calm,’ Goebeler recalls. ‘We had a lot of respect for the Kapitän‘s self-control, even though our boat looked like an ostrich, with our head buried in the water and our tail up in the air!’

In another incident illustrating his leadership, Loewe sailed U-505 across the equator during a lull in the mission, allowing the men to perform the time-honored initiation rituals of Neptune. By the time U-505 reached its base in Lorient, the 50 men on board were a proud and professional crew. Shared dangers, pride in their successful run and confidence in their captain had all combined to produce the kind of team spirit that would be needed to survive the terrifying events to come.

U-505‘s safe return to base was a cause for celebration in Lorient. But there was also a deep sense of relief because the Bay of Biscay, patrolled by growing numbers of prowling Allied bombers, was rapidly becoming known as ‘the graveyard of the U-boats.’

To keep morale high in the face of mounting losses, the naval high command ensured that U-boat crews enjoyed luxuries unavailable to fighting men in the other branches of the German armed forces. Goebeler remembers his days in Lorient with nostalgic satisfaction: ‘The navy really treated us first class. They had a band there to greet us, and we had lots of time to relax. Of course, we had constant training to learn about new equipment, but we were free during many evenings to enjoy the town. There was a soldiers’ theater where we could see German movies, and they made sure we had plenty of fresh fruits, white bread, sausages and beer. And not the ersatz beer that everyone else drank; we had the real thing! And there were women, too. There was a place soldiers could go where the women were inspected regularly so that they wouldn’t get…sick. But there were so many French girls that I never had to go there. The French treated us U-boat men very well, even after the British started bombing the place.’

The weeks passed quickly as U-505‘s engines were overhauled and a fresh supply of torpedoes loaded on board. The crew, proud of their sub’s successful maiden voyage, was eager for more action. Admiral Donitz himself had visited U-505 upon her return and written in her war diary, ‘First mission of Captain with new boat, well and thoughtfully carried out.’ But he had also felt compelled to add, ‘Despite long time in operations area, lack of traffic did not permit greater success.’

For the next war patrol of U-505, lack of traffic was not expected to be a problem; Donitz had decided to send the boat to the fertile hunting grounds of the Caribbean. On June 7, 1942, exactly one month after her return from her first patrol, U-505 slipped out of port, bound for American waters. Loewe raced across the Atlantic, running almost the entire trip on the surface, using the diesel engines. Allied escort carriers had not been deployed yet, and the crew felt safe enough to lounge topside, sunning themselves. At one point they even set up a mess table on deck and enjoyed lunch alfresco.

As they approached the Caribbean, however, the war once again intruded. On June 28, the crew’s afternoon sunbathing was interrupted by the sighting of a large American freighter. Loewe maneuvered in front of the zigzagging 6,900-ton ship and fired two torpedoes into her. It was typical of Loewe’s sense of honor and humanity that he waited a full hour, to allow the ship’s crew to board lifeboats, before sinking her with a third torpedo. U-505‘s luck continued the next day — the crew sighted another American freighter, the 7,400-ton Thomas McKean. Once again, Loewe fired a double shot of torpedoes to stop the ship and allowed the crew to escape before finishing her off, this time with deck-gun fire.

For Goebeler, the attack on Thomas McKean remains one of the incidents of the war that he remembers with great emotion. ‘Some of the freighter’s crew were hurt, so we gave them medicine and directions where to row to safety,’ Goebeler recalls. ‘A lot of people think German U-boat men sank ships without mercy, but if we had a chance, we always tried to help their crews. After all, they are humans, too. It was only later in the war, when the airplanes were attacking, that we couldn’t wait around after firing torpedoes. Since the end of the war, I’ve attended some reunions with former enemies. We all cried and hugged each other like brothers. We never hated the Americans; we were just doing our duty, just like the boys on the ships hunting us.’

U-505‘s double success seemed to have frightened away all other shipping in the area. For the next month, the sub spotted nothing but Allied aircraft. She had to crash-dive an average of more than once per day to avoid attack. Then, on July 22, a seemingly insignificant incident spelled the end of Axel Loewe’s tenure as captain of U-505. ‘We spotted a three-masted schooner flying no flag that was making violent zigzags back and forth,’ Goebeler remembers. ‘Not the kind of zigzags a sailing ship makes to move across the wind, but the kind a ship makes to avoid torpedoes. This made us suspicious, so we surfaced, and the Kapitän ordered a shot to be fired across her bow. Well, the deck officer must have misunderstood his order because the first shot took off the ship’s mainmast, and that ship wasn’t a sailing ship any more! We couldn’t leave the evidence floating around, so we sank her with the deck gun.

‘The boat turned out to be the property of a Colombian diplomat, and the incident caused Colombia to declare war against Germany! Well, at that point in the war, having Colombia declare war against Germany was like a dog howling at the moon; it doesn’t matter to the moon at all. But Kapitän Loewe blamed himself. We finally had to stop our patrol and return to Lorient earlier than planned. Loewe was having very bad trouble with his appendix, but I think his worry over the sailing ship was the main problem.’

Admiral Donitz’s comment in U-505‘s war diary was that the sinking of the schooner ‘had better been left undone.’ Loewe was relieved of his command and assigned to shore duty as a member of Donitz’s staff. U-505‘s second war patrol, which had begun so auspiciously, had ended in frustration.

Captain Peter Zschech came to U-505 with a very high reputation. As first watch officer of U-124, he had been trained by Jochen Mohr, skipper of a crew that had sunk more than 100,000 tons of Allied shipping. However, being commander of a submarine is a different matter. Although he chose a new emblem for U-505 that graciously incorporated the ax symbol of Loewe’s command, it was clear that Zschech was very sensitive on the issue of who the captain was now. Over time, the crew’s natural goodwill and respect for their new commander began to erode.

On October 4, 1942, U-505 sailed on her third war patrol, operating once again as a lone wolf in the area around Trinidad. Relations between captain and crew worsened as Zschech’s bullying personality became more pronounced. Even the crew’s continuing success against Allied shipping did not help improve morale. On November 7, U-505 sank a 5,500-ton freighter, but other targets escaped when the engineering officer raised the periscope too far, alerting the intended victims.

The last straw came at noon on November 10. Planes from the British air base on Trinidad had been constantly harassing the boat for weeks, and the second watch officer, noting the cloudy conditions that Captain Loewe used to call ‘perfect air surprise weather,’ suggested to Zschech that the lookouts be doubled. Zschech responded angrily to the implied comparison between himself and the former captain.

Goebeler remembers clearly what happened next: ‘A lookout suddenly shouted the alarm, and a second later there was a gigantic explosion. We had suffered a direct hit by a bomb that nearly tore the boat in half. The airplane that dropped the bomb was itself destroyed by the blast, and it crashed into the ocean next to us. The body of one of the pilots was lying on a part of a wing that was floating nearby, but we didn’t have time to think of him. The Kapitän gave the order to abandon ship, but the chief petty officer said, `Well, you can do what you want to do, but the technical crew is staying on board to keep her afloat.’

‘Other boats with the same damage might have sunk, but our crew knew what to do, and we did keep her afloat. That lucky boat, U-505, was the most heavily damaged German submarine to ever get back to base during World War II. Two days after the bombing was my birthday, so now I celebrate my birthday on both days because it is a miracle we survived.’ It took six months of intensive repairs before U-505 was ready for action again. On July 3, 1943, she set sail on her fourth war patrol, but after only four days a series of serious malfunctions forced her to return to base. Back in Lorient, it was discovered that shipyard workers had sabotaged U-505.

The next two missions were also aborted due to shipyard sabotage. One often-used trick was to undermine the integrity of the hull by packing ropes into welding seams. Another ingenious trick involved drilling a small, pencil-sized hole in the fuel tank that caused U-505 to trail a line of diesel oil, which could be spotted miles away by Allied aircraft. At one point, Goebeler himself was instrumental in the arrest of a saboteur whom he had overheard gloating to his friends in a tavern.

The damage to U-505 was minimal compared to the corrosive effect recent events were having on Zschech’s morale. During the time U-505 was in the dockyards for repairs, several of Zschech’s closest friends were killed in action. Ugly rumors circulated among officers and men alike regarding his competence and bravery, exacerbating his depression. When U-505 sailed on her sixth war patrol, Zschech finally cracked. Goebeler was there when it happened. ‘We were being depth-charged very closely by some destroyers,’ he recalls. ‘All the lights were out, and we had been knocked off our feet by the explosions. I looked over and noticed the Kapitän and saw him slowly begin to lean over. The radio petty officer came out of the radio room and carried him to his bunk. When the lights came on, I saw the blood and found out he had shot himself in the head with his pistol during the depth charge attack. The depth-charges were so loud I never noticed the sound of the pistol.’

Quick thinking by first watch officer Meyer enabled U-505 to escape the destroyers. The crew was informed of the captain’s death, but only those in the control room knew exactly how he had died. A few hours later, Captain Zschech’s body was buried at sea, and U-505 turned back toward Lorient.

The third and final captain of U-505 was Lieutenant Harold Lange, an older, almost fatherly reserve officer who was hand-picked by U-boat headquarters to take over. The new commander desperately needed a morale booster for the crew, and an opportunity presented itself almost immediately.

Sailing from Lorient on December 20, 1943, U-505 was in the middle of the Bay of Biscay when the crew heard the sounds of gunfire. Sixty nautical miles away, a battle between British cruisers and a small force of German destroyers and torpedo boats was taking place. Realizing that survivors would not last long in the frigid winter waters, Donitz ordered Lange to race U-505 to the battle area on the surface. As dawn broke, the crew rescued 34 survivors from torpedo boat T-25, including the captain. The rescue of the sailors made the crewmen of U-505 heroes.

Mechanical problems continued to plague U-505, however, and the crew was stranded in the submarine base at Brest for 10 weeks while her diving planes were repaired. On March 16, 1944, the boat left Brest Harbor to prowl her old hunting grounds off Freetown, West Africa. It was to be her last patrol of the war.

Allied shipping had moved away from Freetown to the Mediterranean, leaving U-505 to her fruitless search for targets. As Lange steered back to Lorient, American aircraft buzzed the boat almost constantly. Aircraft and coastal radar alerts were so frequent that the sub could not even stay surfaced long enough to charge her batteries. As Lange suspected, the U-boat was being hounded by a carrier task group — one that had sunk two of U-505‘s sister boats from Lorient only a few weeks earlier.

The carrier in question was the escort carrier USS Guadalcanal, which, in conjunction with four destroyers, formed hunter-killer Task Group 22.3. The group was commanded by Captain Daniel V. Gallery, one of the most talented and determined American sub-hunting skippers of the war. On April 9, the task force had forced U-515 to the surface and destroyed her with gunfire. The enormous amount of firepower the boat endured before she finally sank gave Gallery the idea that it might be possible to capture a U-boat before she was sunk or scuttled. Plans were drawn up, and men were trained for such an opportunity. On June 4, 1944, Gallery’s men got their chance.

On that day, shortly after 11 a.m., U-505‘s faulty sound detection equipment picked up faint propeller noises. When Lange rose to periscope depth to investigate, the sight he saw made his blood run cold. U-505 was in the midst of a carrier task group and about to be attacked by three destroyers and several aircraft. The boat immediately dived, but freakish water conditions allowed the aircraft to see the sub and use bursts from its .50-caliber machine guns to mark her submerged position for the destroyers.

‘They really gave it to us!’ Goebeler remembers. ‘They fired hedgehogs and about 64 depth charges at us. The explosions were the biggest I ever heard. One depth charge was so close it damaged torpedoes stored in the upper deck. Other depth charges jammed our main rudder and diving planes. Lange managed to fire one torpedo, but soon there was nothing for us to do but surface and abandon ship before she sank for good. When we reached the surface, Lange opened the hatch but was wounded right away by the gunfire. Men started jumping overboard, but I stayed in the control room to make sure the boat sank. It was the chief engineer’s job to set the demolition charges and scuttle her, but he was already in the water, trying to save his own neck. The boat wasn’t sinking because she was hanging on the air bubble in diving tank No. 7. We tried by hand and by air pressure to open the relief valve for the tank, but it wouldn’t budge because the relief valve shaft had been bent from a depth charge explosion.

‘I went behind the periscope housing and took off the cover of the sea strainer. This let an 11-inch stream of water into the boat and I thought, `This will do it!’ I climbed topside and helped four other men get a big life raft loose. The destroyers and planes were giving us hell, firing anti-aircraft, anti-personnel and high-explosive weapons at our boat. We swam away from the sub as quickly as possible. The planes were shooting the water between us and the boat, chasing us away from U-505 like a cat playing with mice. But none of us was crazy enough to want to go back to that boat because she was sinking fast! Only the very front of the boat and the top of the conning tower was still above the water. Well, the American skipper must have had some men who were very brave, or very crazy, because they boarded the sub, found the sea strainer cover and closed it. They somehow kept the boat afloat and took it in tow.

‘We were picked up by destroyers and brought to the carrier, where they locked us in a cage just below the flight deck. The heat from the carrier’s engines was so terrible that we lost 20 or 30 pounds during those weeks from sweating. They brought us to the Bermudas for about six weeks, where we gained some weight and began looking human again.

‘We were transported to Louisiana and sent to a special prisoner-of-war camp for anti-Nazis. You see, that particular camp wasn’t covered by the Geneva Convention. The Americans didn’t want the Red Cross to interview us and let our navy know that a U-boat had been captured. We worked there in Louisiana on farms and in logging camps until 1945, when we were transferred to Great Britain. We were confined there until December of 1947, when we were finally released.’

Through an incredible series of events, U-505 survives today, on display at Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry. More than half a million visitors a year tour the boat’s decks and gaze at her battle-damaged conning tower.

Hans Goebeler lives in semiretirement in central Florida with his wife and daughter. He makes a modest living selling coffee mugs emblazoned with pictures of famous U-boat captains and other German war heroes, and his eyes still sparkle with life when telling about his days aboard the U-505 — the U-boat that wouldn’t die.

This article was written by John P. Vanzo and originally appeared in the July 1997 issue of World War II magazine.