Götterdämmerung—“Twilight of the Gods”—Adolf Hitler’s parting legacy to Europe. Nothing was to be left for the victorious Allies. Where there had been cities, they would find rubble. Where there had been cultivated fields, they would find wilderness. The Führer and his henchmen came close to achieving this goal. Agricultural production had ground to a halt, while in urban centers millions had been bombed out of their homes and were living on the edge of starvation. Distribution of the limited stockpiles of food was severely constrained by the smashed state of Central Europe’s rail and transport infrastructure. To the west the population was swelling daily as an estimated 12 to 14.5 million fled Russian-occupied territory. Survivors of the Nazi slave labor and death camps were in desperate need of aid, as were thousands of newly released Allied POWs. The Western Allies and Soviets were forced to make some tough choices concerning German and Axis prisoners of war.

Under the 1929 Geneva Convention, POWs were entitled to a diet equivalent to that of the occupying troops. Given the circumstances in Europe at the end of the war, however, a 2,000-calorie diet, the recommended daily minimum, would have been impossible to maintain. The bulk of Allied shipping was now earmarked for the Pacific theater; only when the war had been won would supplies be diverted to Europe.

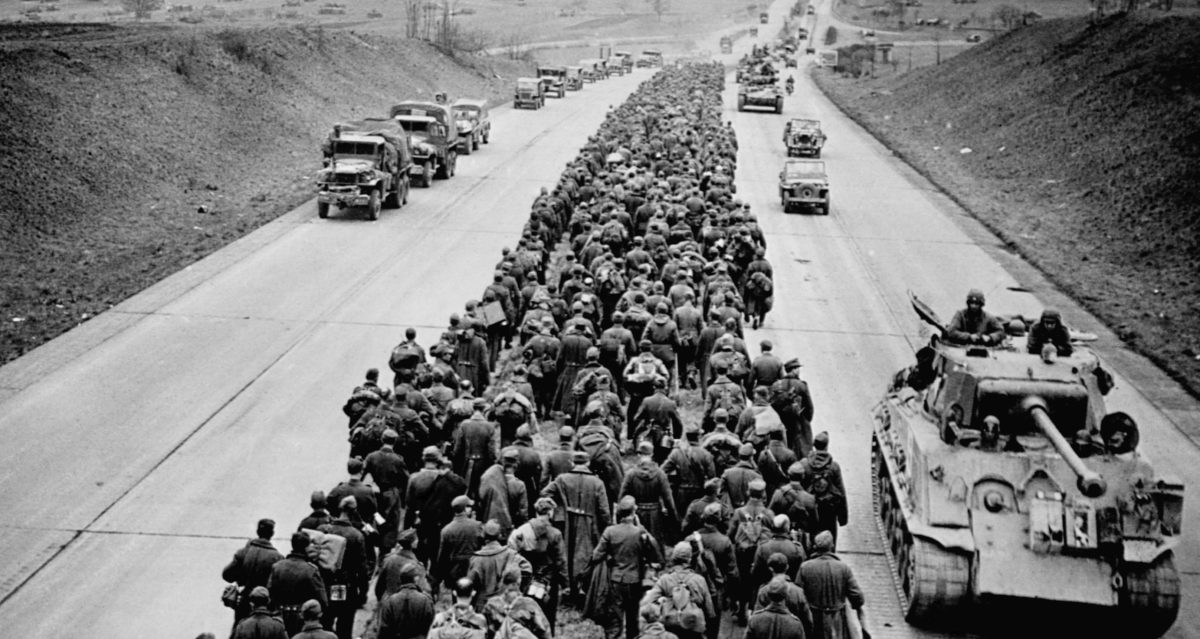

In early April 1945, the United States was responsible for 313,000 prisoners in Europe; by month’s end this total had shot up to 2.1 million. After the fall of the Third Reich, the number rose to a staggering 5 million German and Axis POWs. Of those, an estimated 56,000, or about 1 percent, died—roughly equal to the mortality rate American POWs suffered in German hands.

Those held in Soviet-occupied territory fared far worse. Officially, the Soviet Union took 2,388,000 Germans and 1,097,000 combatants from other European nations as prisoners during and just after the war. More than a million of the German captives died. The immense suffering Germany and her Axis partners had caused surely played a key role in the treatment of enemy POWs. “In 1945, in Soviet eyes it was time to pay,” wrote British military historian Max Arthur. “For most Russian soldiers, any instinct for pity or mercy had died somewhere on a hundred battlefields between Moscow and Warsaw.”

Josef Stalin’s regime was ill equipped to deal with prisoners: In 1943 as more enemy units fell into Soviet hands, death rates among POWs lingered around 60 percent. Roughly 570,000 German and Axis prisoners had already died in captivity. By March 1944, conditions began to improve, but for economic reasons: As its manpower was swallowed up in the war effort, the USSR turned to POWs as a surrogate work force. While POWs were not technically part of the gulag system, the lines were often blurred. Camps and detainment centers often comprised poorly constructed huts that offered scant protection from bitter Russian winter winds. The Soviet Union repatriated prisoners at irregular intervals, sometimes in large numbers. As late as 1953, however, at least 20,000 German POWs remained in Russia. After Stalin’s death, those men were finally sent home.

As a young teen in 1939, Milan Lorman witnessed the Nazi dismemberment of Czechoslovakia and the creation of Slovakia as a satellite state of the Third Reich. Lorman’s father, a poor country teacher, diligently traced the family’s Germanic roots to claim entitlements offered by the Third Reich to those of German origin. But there was a cost for such subsidies: In 1943 a letter arrived asking Lorman’s father why his son, now 18, had not volunteered for the SS. The letter alluded to the cessation of entitlements should the teenager fail to join. Under great pressure, young Lorman accepted his fate and volunteered for the Waffen SS.

Following basic training, Lorman’s unit of field engineers was sent to Greece, then on to the Eastern Front. There, in early 1945, as the Red Army advanced, he was promoted to NCO and joined roughly 1,000 men in an intensive training program. But with news of a Russian breakthrough at nearby Poznan, the trainees were rushed to the front. Casualties were high. By April 18, 1945, just 60 remained in Lorman’s unit, fighting desperately alongside a canal between the Oder and Neisse rivers. By that afternoon, only 17 men were left, so a surviving sergeant gathered the men and ordered them to make for headquarters—wherever that might be.

Emerging from the forest, a relieved Lorman stumbled toward a group of 10 or so men, thinking they were a detachment from a Hungarian unit that had been stationed on Lorman’s left. He was wrong. They were Red Army troops, and they beckoned him on. The Russians were amazed to find they had bagged a Slovak in the SS, and a White Russian to boot. Whites were considered traitors and could expect a long confinement in the worst of the gulags—or a bullet.

Asked whether he had any cigarettes, Lorman handed over his stash and was pleased to see they gave some back. “I began to hope that I shall survive this experience,” he recalled. “Surely they would not bother handing back those cigarettes to a man they were about to kill.”

The smoke break was cut short, however, by incoming fire from the woods. A Russian NCO ordered Lorman to stand up and call for the shooters to surrender. Lorman realized the danger he faced: Stand up and get shot, or refuse the order and get shot, but at close range. He jumped up, called out and received a burst of gunfire in reply. Only one bullet hit him, passing through his thigh. Following that action, the Russian NCO had Lorman patched up and sent to an aid station. That night Lorman slept in a goat sty with other POWs.

“There are honorable soldiers in all armies,” Lorman said, “and I was fortunate enough to fall into the hands of some of them.” Those feelings wouldn’t last.

The next morning Lorman watched as a Red Army soldier frolicked with a golden duckling in the spring sunshine. When called to report to a nearby house, the man suddenly dashed the bird to the floor and crushed it dead under his boot heel. For Lorman, it was a terrifying moment. “I don’t want to believe that the central actor in this story was really a Russian,” he recalled. “I cannot describe my feelings at the time. Later when the initial shock wore off, I told myself to be very wary of these people. From that day on I was determined to humor them and to avoid the fate suffered by the beautiful duckling.”

Lorman was sent to a hospital in Swiebodzin to recover from his wounds. The facility sheltered about 120 prisoners. “All of us were wounded or sick,” he said, “but with each new day more and more of us were recovering.” The nurses put the German and Axis POWs to work as orderlies, helping the wounded to the operating theater, cleaning the grounds and burying the dead.

As Lorman realized the hospital was a comparative oasis of calm, perhaps vital to his chances for survival, he improved his language skills and became a translator. “I didn’t miss a single opportunity to strike up a conversation with one or another of the Russians,” he said.

Others were less willing to cooperate. One evening a German officer and his men refused to clean the hospital yard, claiming it was against the Geneva Convention to work after the last meal of the day. Lorman and others broke ranks and started to clean up, while those who had protested, including the officer, were whisked away—to the gulag.

Ironically, that deportation improved conditions at the hospital: “With the number of prisoners now down to less than 40,” said Lorman, “our lives took on an even more peaceful character. We had good food and enough of it, soft enough beds and warm enough blankets, even plenty of books to read.”

In October 1945, a Russian major at the hospital told Lorman his group was to be repatriated. The major then asked coolly whether he should allow the SS men among the group to return. “Why not?” replied Lorman. “They also have homes to go to.” The major knew well enough Lorman had been SS and was just toying with him. On October 13, 1945, he was given his discharge papers.

Traveling with a friend, Lorman headed west, hoping to reach his family’s last known address, a house in the Austrian province of Steiermark. On October 18, the two arrived in the ravaged remains of Berlin and headed for the French sector. Lorman’s friend was a French national from Alsace-Lorraine, and to continue on their journey, they would need proper documentation. They headed to a French military police station to file the necessary paperwork. Instead, both men were handcuffed and detained.

On discovering their detainees were former Waffen SS soldiers, the French authorities threw Lorman into solitary confinement in Tegel Prison while taking the man from Alsace-Lorraine for questioning elsewhere.

Stuck in a cell measuring 6 by 12 feet, Lorman now had to contend with loneliness and lack of exercise. “I didn’t have any contact with the occupant of the neighboring cell,” he said. “All I did see day after endless day was the same cramped cell.”

“The food we were given was not quite enough for survival, only for gradual dying,” said Lorman. “But to be fair, few people outside the prison gates were eating much better. By the end of the first nine months of this existence my weight was down to 103 pounds (I was 6 feet tall), and my morale was lower than the proverbial snake’s belly.”

In desperation, Lorman hatched a plan to gain his warders’ attention. Complaining of sporadic headaches, he managed to hoard about a dozen aspirin, which he hid in his cell. When they found his stash during the next cell inspection, the guards asked Lorman for an explanation. “I intend to kill myself,” he cried out. “Just look at me!”

The ploy worked, and the French authorities granted Lorman contact with other prisoners and even a job in the cookhouse. “Even though after each day’s work I still had to return to my single cell,” he said, “both my spirit and my body soon recovered.”

Lorman was finally released on February 19, 1947, when he was 23. “I was set free into the chaotic postwar world to fend for myself,” he recalled. But it would be years before Lorman and his family would be reunited.

Rudi Janssen experienced detention at the hands of the British. A country lad, he volunteered for service a year early at 17 in the first months of 1943 and was later called up to the Waffen SS. Trained as a signalman, he eventually arrived on the Eastern Front with a panzer unit in 1944. In early 1945 the Red Army started its drive into Nazi territory. One branch of its offensive swung north and cut off some German units in the east—including Janssen’s—from the rest of the Reich.

Pushed back to positions near the Bay of Danzig, Janssen and his comrades endured a heavy artillery barrage that lasted several days while higher command attempted to evacuate the unit. “Now there was a real feeling of defeat,” he said, “a resignation that it was the end.”

Those lucky enough to be evacuated were taken to positions on a nearby peninsula, though still within range of the Red Army guns. Wounded in the leg by shrapnel during the bombardment, Janssen was later evacuated to Rostock by fast boat.

“After a few days convalescing, a doctor came round to our ward and told those of us who were ‘walking wounded’ that the Russians would be arriving soon,” he recalled. “And that those who wanted to move out should do so now.”

Janssen and five comrades went to a nearby station and jumped on a westbound freight train. When the train stopped seemingly in the middle of nowhere, Janssen and a comrade traveled on by foot until they arrived at Travemünde, near Lübeck, on May 3.

Janssen’s wound wasn’t healing properly, so he went to the hospital, where he was told to stay in the waiting room. He decided to head back to the Trave River and dispose of his pistol and paybook. Returning to the hospital, he soon heard the approach of military vehicles. The British were coming.

After being searched for weapons, the German troops in the hospital were told to await further instructions. “That evening a British officer arrived and in very good German informed us that there was no room in the hospital, and that the British would try and accommodate us somehow,” he said. “Later that night, the British came back. They had pulled a train of cattle trucks into the station. They had straw on the floor of the trucks, and we were put into the trucks and locked up. Guards were placed on the platform.This was my first night of captivity.” On the next day they were moved into a hotel.

After a few days, the British separated the SS men from the rest of the prisoners and sent them, including Janssen, to a newly liberated concentration camp near Hamburg. “Here our lives as prisoners really started. It was pretty rough and still a little cold, as it was mid-May. There were no blankets, and we slept on concrete and were questioned frequently, although not every day….None of us could speak English, and none of our guards could speak German, so there was no way of making conversation.”

After 10 days or so, they were moved to a large bordered-off zone in the Schleswig-Holstein region where again there was no accommodation. “We slept in farm buildings and in hay,” Janssen recalled, adding “some had made temporary holes in the ground, with a roof made of sticks and brush and covered with sods of turf. We were left to our own devices. As far as food was concerned, we had to grab what we could. A lot of stealing was going on—we grabbed potatoes from the fields. Ears of corn were stripped off around the cornfields. Most survived.”

One day a batch of British soldiers arrived and announced they were looking for volunteers from among the POWs. Janssen put his name forward and soon found himself working as a clerk processing repatriation papers. Tellingly, those prioritized for return worked in agriculture or food production.

In early 1946, his job as a clerk over, Janssen was put onto a train of cattle trucks that was locked up and then started to roll. “We had no idea where we were going and how long the journey would take,” he said. “Finally coming to a halt, we discovered that we had arrived in Belgium. All of us from the train were taken to a camp that I believe was at a place called Berchan. This camp was split into ‘cages,’ with up to roughly 6,000 POWs in each one. The camp population, I believe, was close to 36,000 POWs.The situation here was pretty rough, and we often went hungry.”

On April 6 Janssen joined a detachment sent to England. The men were given hearty rations at a transit camp. “[It was] almost like a holiday camp to us,” he recalled. “We could eat as much as we liked, which was fantastic, as by this stage we were quite undernourished.”

Performing various jobs for the British army, Janssen found the conditions not only acceptable but almost comfortable. “Specific skills were needed in different camps at different times,” he said, “and if you had a skill you found yourself moving about quite a bit. If you spoke good English, you would be used as a squad leader and, importantly, an interpreter—a skill much in demand.”

In 1948, his last year of captivity, Janssen took up a British offer to extend his time in England as a farm laborer in return for regular pay and the opportunity to wear civilian clothes. Living in rural Surrey and by then fluent in English, Janssen felt himself integrated with the local community. When he returned to Germany on Christmas 1948, he took up another offer for former POWs to go back to Britain and continue working as agricultural laborers. Soon after he returned in 1949, he married. For Janssen, despite some tough times at the start, being a POW had led to the happiest of conclusions.

For further reading, Simon Rees recommends Eisenhower and the German POWs: Facts Against Falsehood, by Günter Bischof and Stephen E. Ambrose.

This article was written by Simon Rees and originally published in the May 2007 issue of Military History Magazine. For more great articles, subscribe to Military History magazine today!