Forged in the furnace of the Civil War, the 7th Regiment Iowa Volunteer Cavalry fought the same warrior tribes as the 7th U.S. Cavalry under Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer, with victories and defeats and a record that was sometimes reputable and sometimes controversial but never as dire as what happened to Custer’s men on the Little Bighorn in Montana Territory a decade later. The 7th Iowa was perhaps typical of the Volunteer regiments that fought Plains Indians during the waning days of the war and in the months after Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s April 1865 surrender in Virginia at Appomattox Court House.

Samuel W. Summers and Herman H. Heath took the lead in forming the 7th Iowa in Davenport through the latter half of 1862, and in late April 1863 the regiment consolidated, two companies mustering in on April 27, two on April 28, two on June 3, one on June 16, and one more on July 13. The U.S. War Department then transferred in the three companies of the disbanded 41st Iowa Volunteer Infantry—presumably men who knew something about horses—and a company of municipal cavalry from Sioux City. Summers, a Virginia-born attorney and man of property from Ottumwa, was appointed colonel of the 7th Iowa. Canadian-born John Pattee—Iowa’s onetime state auditor, formerly of the 41st Infantry—was appointed lieutenant colonel, and Heath served as one of the regiment’s three majors.

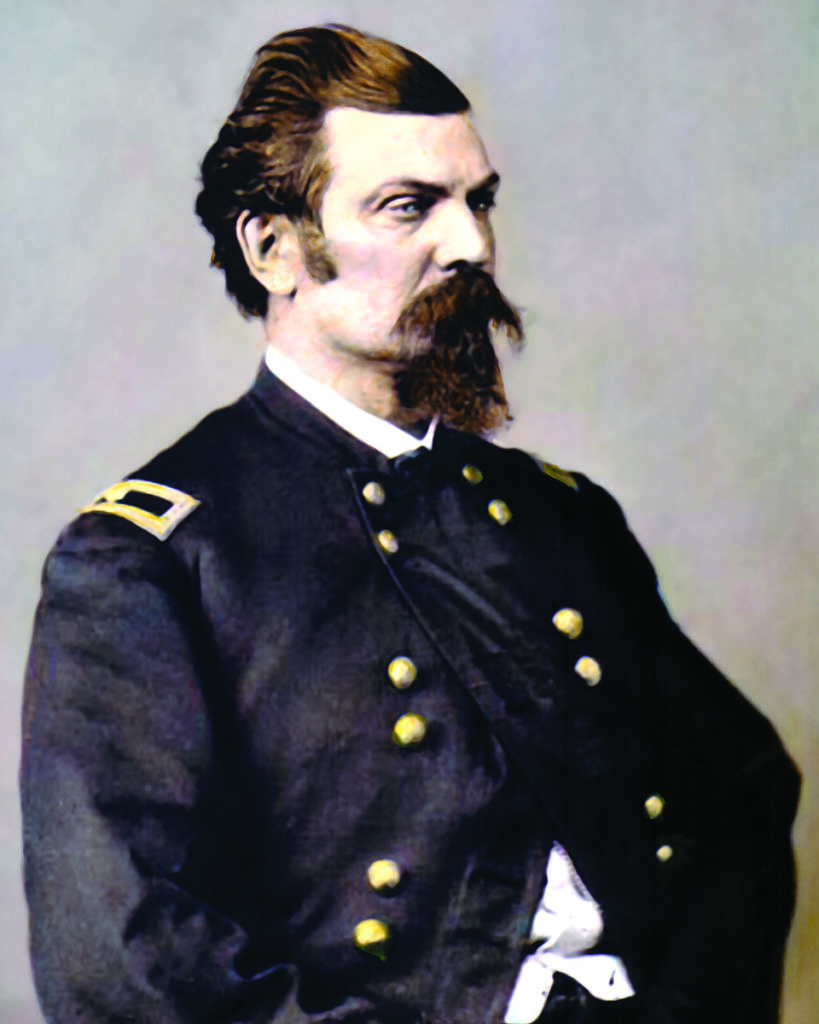

Heath, born in New York in 1823, was a postmaster in Dubuque at the outset of the war and had been elected a first lieutenant in the 1st Regiment Iowa Volunteer Cavalry. He was soon promoted to captain. On Aug. 2, 1862, Heath was wounded leading the 75 men of his company in an attack against several hundred concealed Confederate guerrillas at Clear Creek near Taberville, Mo., reportedly “running a flank along a double line of shotguns and Minié muskets at 30 yards.”

Even before the completion of recruiting, Major Heath led six companies of the 7th Iowa west to Omaha, Nebraska Territory. There he reported to Brig. Gen. Thomas J. McKean, commanding the military subdistrict, who dispersed the individual companies to various posts in the territory. Colonel Summers led out the remaining companies that fall, establishing the regimental headquarters at Omaha. After more than a year spent escorting emigrant wagon trains and guarding telegraph lines and travel routes, the 7th Iowa would be tested in battle.

In the aftermath of the massacre of peaceful Cheyennes and Arapahos at Sand Creek, Colorado Territory, by Volunteers under Colonel John Chivington on Nov. 29, 1864, the 7th Iowa by necessity turned to defending settlers against reprisal attacks by vengeful Indians.

In the regiment’s first major action in January 1865, Captain Nicholas J. O’Brien led out Company F after Indians attacked a wagon train near Julesburg, in far northeastern Colorado Territory, a stagecoach relay station, express/telegraph office and general store about a mile from the Army’s newly constructed Fort Rankin (later Fort Sedgwick). The Indians, numbering upward of 1,000 warriors, included Cheyenne Dog Soldiers presumably led by Roman Nose, Northern Arapahos, Brulé Lakotas under Spotted Tail and Oglala Lakotas under Pawnee Killer. On January 7 a party of 10 warriors feigned an attack on Fort Rankin and then fled, hoping to lure soldiers into an ambush. Captain O’Brien obligingly gave chase with the 60 troopers of F Company and a handful of civilian volunteers. When the sortie had gotten about 300 yards from the fort, excited young warriors fired prematurely from concealment, tipping the ambush. O’Brien and his men promptly turned tail back toward Fort Rankin, the Indians at their heels.

Colonel Summers, who had ridden out with Company F, was cut off and besieged with a group of troopers and civilians at a ranch. The siege continued until O’Brien, who’d managed to reach the fort, rolled out artillery and dispersed the Indians with the one weapon they couldn’t match or withstand. According to the after-action report, Company F suffered 14 enlisted men killed, while the Indians lost 55 warriors. Summers himself was said to have shot the principal chief and looted his regalia. George Bent, a half-blood Cheyenne who’d lost friends at Sand Creek and participated in the ambush at Julesburg, later claimed the Indians hadn’t lost a single warrior. Whatever the truth, the Indians plundered the abandoned buildings at Julesburg and carried off enough loot to offset any disappointment over the failed ambush. Summers was quietly mustered out of the Volunteer service later that month.

Brigadier Gen. Robert Mitchell responded to the attack on Julesburg by mustering a force of 640 cavalrymen, a battery of howitzers and 200 supply wagons and moving against what he thought would be the war party’s next camp, on Cherry Creek. He found it on January 19, but the Indians had already vamoosed. The only contact with the Indians came when a raiding party rode through Mitchell’s camp one night firing into the soldiers’ tents. Meanwhile, the bitter cold sidelined 50 men with frostbite. Mitchell gave up the pursuit.

The war party of Lakotas, Cheyennes and Arapahos had returned north to the Black Hills and Powder River country for the winter, raiding stagecoach stations and ranches along the way. The Lakotas struck east of Julesburg, the Cheyennes to the west and the Arapahos in-between. Bent described a raid in which the Cheyennes captured 500 head of cattle and skirmished with a detachment of troopers. But the attackers went mostly unopposed. Bent reported the war party killed nine white civilians they recognized as having participated in the Sand Creek massacre. The warriors mutilated their corpses.

On April 2 the Indians again attacked Julesburg, stealing all remaining supplies and setting fire to the buildings while some 15 soldiers and 50 civilians sheltered within Fort Rankin. Captain O’Brien and 14 troopers who’d been on patrol circled back under cover of the smoke and lobbed a field howitzer round into the Indians. Those within the fort fired a second round, and the Indians gave way, enabling O’Brien and his men to rejoin the garrison. The action may have inspired the captain’s Lakota nickname, O-zak-e-tanka (“Big Soldier”).

But the Indians were hardly done.

On April 3, the Indians burned a telegraph station on Lodgepole Creek. The next day an advance party of Lakotas appeared at the stagecoach station and telegraph office at Mud Springs. The nine soldiers and five civilians sheltered within its sod and log walls settled in for a siege, and both sides blazed away, mostly with seven-shot Spencer carbines, though some warriors also used single-shot trade muskets and bows and arrows. As the Indians ran off 18 horses and a herd of cattle, the telegraph operator got off a message to Fort Mitchell, 45 miles to the northwest, and Fort Laramie, another 45 miles up the line.

Riding all night from Fort Mitchell, Lieutenant William Ellsworth and three dozen troopers reached Mud Springs around the same time as the main body of Indians, estimated at 1,000 warriors. Ellsworth sent a 16-man detachment to a nearby bluff to protect the approaches to the station, but the warriors spotted the move, killing one man and driving the survivors back to the station. The beleaguered soldiers resorted to a stratagem, releasing the remaining corralled horses at the station, which a number of Indians promptly chased, hoping to secure fresh mounts. The others withdrew to their camp, some 10 miles east.

At 2 a.m. on April 6, Colonel William O. Collins reached Mud Springs with an escort of two dozen of his best troopers, and at dawn the rest of his command, another 120 men, caught up. The garrison at the station now numbered some 170 soldiers. To protect his horses, Collins corralled four wagons and placed the animals inside. When the Indians renewed their attack that morning, some dropped arrows down into the corral, killing or wounding several of the mounts. The colonel responded by sending two detachments in a limited attack to drive the Indians out of bow range. That night Lieutenant William Brown reached Mud Springs with another 50 soldiers and a 12-pound howitzer. Collins resolved to attack the Indians in force on April 7, but by then they had drifted away. The Army lost one man killed and a handful wounded compared to an estimated 30 Indian casualties. Bent again claimed the Indians hadn’t lost a man, though he admitted three warriors had been killed in a separate attack on a wagon train.

On April 8, Colonel Collins and 185 of his troopers caught up with the Indians on Rush Creek. The young men and women in camp had spent the previous night dancing, with husbands and fathers drumming and wives cooking, and most were sleeping it off. At 2 p.m. a lone Lakota sentinel spotted the approaching soldiers. The warriors promptly mounted and rode out to engage the troops. Collins had his men employ the howitzer to keep the Indians at bay, though some of the shells turned out to be duds. When a group of Indians moved into effective rifle range, Lieutenant Robert Patton of the 11th Ohio Cavalry asked Collins’ permission to charge out with 20 select men and disperse them. The Indians countercharged in larger numbers than expected, forcing the soldiers to retreat. Two soldiers were killed in the exchange. In the aftermath soldiers found the body of Private William H. Hartshorn riddled with 97 arrows. That afternoon the warriors kept the troopers at bay while their women and children fled north. On April 10 Collins headed back to Fort Laramie after 10 days, 400 miles of travel and two indecisive battles.

Drawing on interviews with Bent, historian George Hyde reflected on the campaign years later from the Indian perspective:

These Indians had moved 400 miles during the worst weather of a severe winter through open, desolate plains taking with them their women and children, lodges and household property, their vast herds of ponies, and the herds of captured cattle, horses and mules. On the way they had killed more whites than the number of Cheyennes killed at Sand Creek and had completely destroyed 100 miles of the Overland Stage Line.

A tragedy of good intentions befell the 7th Iowa in late June 1865, after the end of the Civil War in the East. Captain William D. Fouts and 138 men drawn from his and other companies were ordered to escort friendly Lakotas from the vicinity of Fort Laramie the 300 miles east to Fort Kearny (on the site of future Nebraska City, Neb.). Fouts, a prewar Methodist minister and circuit rider, was so certain of the Lakotas’ peaceful nature, and equally determined to prevent any accidents, that he had refused to issue cartridges to troopers in the rearguard. He brought along his wife and two younger children, as well as the family of a fellow officer. Also part of the group were Lucinda Eubanks and son Willie, ransomed captives who’d been taken by a Cheyenne raiding party and traded to the friendly Lakotas. Three days out from Laramie the Indians refused to saddle up, reportedly objecting to the plan to resettle them so close to the Pawnees, their traditional enemies. When Fouts persisted, the Lakotas shot the captain and four enlisted men from their saddles. After killing four of their own number who objected, warriors split the skull of the fallen captain with a pickax. The rest of the troopers fled, pursued by Lakotas reinforced by infiltrating hostiles. Captain John Wilcox, Fouts’ top subordinate, reported the subsequent action to headquarters:

The Indians had fled two or three miles to the Platte, the squaws and papooses were swimming the river on ponies, and the warriors, on their war horses, were circling and maneuvering in hostile array. Supposing that a part of the Indians were really friendly and would join us in subduing the rest, I charged on after them. We overtook and passed a few squaws and papooses, whom I forbade my men to injure or molest.

Wilcox formed a skirmish line and watched as the Indians shouted their defiance and then charged the troopers. “In the fight,” the captain reported, “a very few enlisted men I cannot name acted badly, but most of them behaved nobly and some with daring bravery. The officers under my command behaved well. After interring our dead…and repairing the telegraph line broken by the Indians during the engagement, we took up our line of march and arrived at Fort Mitchell after midnight.”

The Battle of Horse Creek went down as a Lakota outrage. “It was very evident,” the Iowa Adjutant General’s Office reflected, “that Captain Fouts was the victim of misplaced confidence in the good faith of the Indians in his charge, and that his death was the first result of their treachery. This trait of character was, perhaps, most notable in the tribe of Sioux Indians.” The Lakotas claimed they, too, had feared treachery—by the soldiers and their Pawnee allies.

That spring Heath, who in Summers’ wake had been commissioned as colonel of the 7th Iowa, had been brevetted brigadier general. He headquartered his command on the Platte River at Fort Kearny. In the summer of 1865 newspapers reported that Indians had attacked a wagon train in the vicinity of Alkali (present-day Paxton, Neb.), some 125 miles to the west along the South Platte. Determined to stop the Indians once and for all, Maj. Gen. Grenville Dodge, commanding the Department of the Missouri, ordered a punitive campaign.

“The citizens of Nebraska and especially those living on and interested in the great overland road,” a period journal wrote in flattering praise of Heath, “may congratulate themselves upon having a military commander who thoroughly understands the mode of Indian warfare, and who is willing to march against them, and to endure the same privations and fatigue that his men do, sharing his rations with them; whose home in the field is in the saddle, and whose movements are as rapid as those of his wily foe.”

Yet according to official Army reports, Heath was not involved in the forthcoming campaign. It was Brig. Gen. Patrick Connor who launched the three-pronged Powder River Expedition against the hostiles who’d sought to avenge Sand Creek or forestall anything similar. Marching with the Western prong was Captain O’Brien of the 7th Iowa, who had lost 14 men and had almost been killed himself during the attack on Julesburg and Fort Rankin. This time the Irish-born captain fielded 100 troopers and two mountain howitzers.

When Jim Bridger, the famed civilian scout, sighted an Indian village in late August, General Connor led out O’Brien’s F Company and another 100 troopers with 40 Omaha scouts and 30 Pawnee scouts. The general had earlier set the tone of the expedition when he’d issued orders not to accept surrender but to “kill every male Indian over 12 years of age.” Arriving at the sleeping Arapaho camp around 8 a.m. on August 29, Conner was able to achieve complete surprise. O’Brien’s artillerymen rained down shells on the camp with the mountain howitzers just before the troopers and scouts charged in shooting. Many of the Arapaho warriors were away raiding the U.S.-allied Crows. In the attack, the Army lost two soldiers dead and a half-dozen wounded, while the Arapahos lost 63 dead (men, women and children) and eight women and 13 children taken prisoner. The soldiers burned the 250 abandoned lodges and captured 500 ponies. Connor released the women and children the next day—much to the disappointment of his allied scouts—with a stern warning for their men to surrender. It fell on deaf ears.

Three days later on Alkali Creek some 300 Hunkpapa, Sans Arc and Minneconjou Lakotas (not part of the original alliance formed in the wake of Sand Creek) went after Connor’s horse herd. Four Indians and three soldiers were killed in the resulting clash. After three more engagements with the main body of Indians—including Cheyennes, Arapahos and all of the Lakota bands—Connor withdrew, first to newly established Fort Connor on the Powder River and then to Forts Laramie and Leavenworth, where most of the Volunteer units were mustered out of service.

The 7th Iowa remained in service until June 22, 1866. In the meantime, its officers and men gradually mustered out.

Discharged on May 17, 1866, Heath, the onetime postmaster turned brigadier general, ventured south to New Mexico Territory. Harboring political ambitions, he was appointed territorial secretary of state by President Andrew Johnson in 1867. But three years later when President Ulysses S. Grant nominated Heath to be U.S. marshal of the territory, detractors made public a letter the general had written to Jefferson Davis in 1861, offering his services to the Confederacy. Grant withdrew the nomination, and the disgraced Heath fled to Peru, where he died on Nov. 14, 1874.

Captain O’Brien—who’d escaped Ireland’s Great Famine as a boy and was steps from being killed in the ambush attack outside Fort Rankin—had a happier postwar outcome. In 1865 he’d married Emily E. Boynton, daughter of a prominent family in Clayton County, Iowa. When the dust settled on the Powder River campaign, the couple moved to Nebraska and settled in Julesburg, where the captain was elected mayor. He later served in Wyoming as a deputy U.S. marshal and the sheriff of Laramie County. The O’Briens eventually settled in Denver, Colo., where Nicholas worked with the U.S. Land Department until his death on July 29, 1916.

The 7th Iowa had enrolled 1,592 men during its three years of service. Of those, 53 were killed in action and 18 were wounded, two later dying of their wounds. Disease claimed the lives of far more troopers—92 in all—while 267 others were discharged due to disease or injury. None were reported captured. Of course, the tribes they were fighting never took adult male prisoners, particularly after Sand Creek.

A side-by-side comparison with the famed 7th U.S. Cavalry, organized just after the Civil War in 1866, is instructive. While the 7th Iowa never achieved a decisive victory over the very tribes Colonel Custer fought, neither did the Volunteer regiment suffer a catastrophic defeat. Its worst loss was 14 men in the failed Indian ambush and subsequent attack on Julesburg and Fort Rankin—a foreshadowing of the Dec. 21, 1866, Fetterman Fight, in which Indian ambushers slew 79 Regulars and two armed settlers. The Little Bighorn, of course, was not an ambush but a surprise attack that backfired because the Indians failed to panic and were heavily armed with repeating rifles and breechloaders. Both 7th regiments killed women and children as collateral casualties, but neither force aimed at Indian extermination. The spectacular death of Custer and the loss of his immediate command on the Little Bighorn was perhaps the only major distinction between them.

Wild West special contributor John Koster, a New Jersey–based freelance writer, is the author of Custer Survivor and Custer’s Lost Scout. For further reading, he also suggests The Indian War of 1864, by Eugene F. Ware, and Iowa and the Rebellion, by Lurton Dunham Ingersoll.