The harsh realities on the ground dictated a big unit strategy to push back the main force so the guerrilla insurgent could be stamped out.

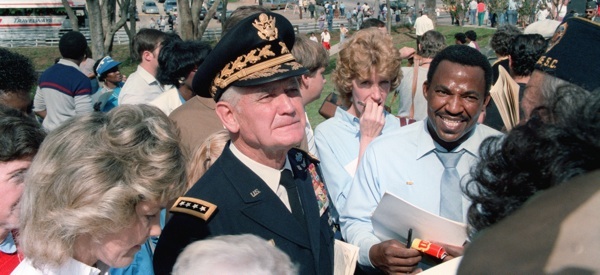

See Sidebar, Westmoreland’s Last Interview.

For better or for worse, the Vietnam War continues to cast a long shadow over how the United States fights wars. It is the standard everyone wants to avoid. “No more Vietnams” has been the mantra for a generation of military planners, policymakers and pundits. Scores of articles and editorials in the past few years have warned against repeating the “mistakes” of Vietnam in Iraq and Afghanistan. For example, military analyst Max Boot has written “The biggest error the armed forces made in Vietnam was trying to fight a guerrilla foe the same way they had fought the Wehrmacht.” While the image of a big army stumbling around after agile guerrillas has come to represent the predominate “lesson” learned from Vietnam, this is in fact a misleading caricature.

Since the United States lost the Vietnam War, historians have rightly concentrated on what went wrong and who was to blame. Two basic schools of thought developed, both arguing that the United States failed to identify the true nature of the war. One side argued that the real center of gravity was in Hanoi, and that the war was really an invasion by North Vietnam, and the guerrillas were largely a sideshow.

The leading proponent of this point of view was Colonel Harry Summers, whose book On Strategy: A Critical Analysis of the Vietnam War argued that the Viet Cong guerrillas provided a distraction so “North Vietnamese regular forces could reach a decision in conventional battles.”

Others believed just the opposite—that the war was fought by a conventionally minded U.S. military that ignored counterinsurgency. Andrew Krepinevich, in The Army and Vietnam, argued that “In focusing on attrition of enemy forces . . . MACV [Military Assistance Command, Vietnam] missed whatever opportunity it had to deal the insurgents a crippling blow at a low enough cost to permit a continued U.S. military presence in Vietnam in the event of external, overt aggression.”

But the reality was that the Communists were able to simultaneously employ both main forces and a potent guerrilla structure throughout South Vietnam, and any strategy that ignored one or the other was doomed to failure. A deeply rooted political infrastructure formed a permanent presence in South Vietnam’s villages while increasingly large military formations could challenge South Vietnamese forces on their own terms.

It was an ideal insurgency, yet this is ignored by most historians. Instead, Summers and Krepinevich are compelling because they argue that there was a simple strategic “choice”—a right way and a wrong way to fight—and the wrong choice was made.

General William C. Westmoreland, the MACV commander, usually gets the blame for making that wrong choice. A leading proponent of this view is Lewis Sorley, who wrote in A Better War: The Unexamined Victories and Final Tragedy of America’s Last Years in Vietnam, that Westmoreland foolishly used a search-and-destroy strategy that could not possibly catch guerrillas dispersed throughout the countryside. Sorley contends that Westmoreland’s successor, General Creighton W. Abrams, switched to counterinsurgency to thwart the guerrillas in the villages rather than continue to fruitlessly chase them in the jungle. “Abrams brought to the post a markedly different outlook on the conflict and how it ought to be conducted,” argued Sorley, switching from “search and destroy” to “clear and hold.”

Indeed, the current belief about strategy in Vietnam is apparent: counterinsurgency will be more successful if it embraces the strategy used by Abrams and rejects that employed by Westmoreland. But this interpretation falls short for two reasons. First, most histories fail to examine what the Vietnamese Communists were actually thinking and doing. Second, many authors assume that Westmoreland misunderstood the enemy he faced and as a result made poor choices in how to fight. Therefore, it is argued, had things been done differently early on, the war might have been won.

The popular conception of the enemy in Vietnam is that it was a grassroots insurgency sprung from the peoples’ discontent with an illegitimate government in Saigon and the presence of a foreign invader. South Vietnam was certainly plagued by an insurgency, and there was popular support for it, but the key ingredient throughout the entire war was North Vietnam. Hanoi controlled the insurgency’s leadership, Hanoi mustered the bulk of the main force units, and Hanoi sent the supplies south to keep the war going.

Following the 1954 partition of Vietnam, the Communists spread their roots in the south, forming the National Liberation Front (popularly called the Viet Cong) in 1960 to control and cultivate the insurgency. Within three years the guerrillas were a serious threat, defeating South Vietnamese Army units in several battles.

Three other important factors benefited the Communists. The first was military support from China and later from the Soviet Union. Chinese sources reveal that between 1964 and 1975 Hanoi received more than 1.9 million “guns” (small arms) and almost 64,000 artillery pieces, ammunition, almost 600 tanks and 200 aircraft.

The second factor was the secure base areas in North Vietnam as well as neighboring Laos and Cambodia that gave the Communists the ability to move troops and supplies to the southern battlefield with virtual impunity—and to do so with little fear of having to fight on their own home ground.

Finally, Hanoi began moving its own troops into South Vietnam in the spring of 1963. According to an official Communist history, a battalion from the 312th Division was sent south, followed by more units over the next year, including the entire 325th Division in the spring of 1964. These units would form the core of a burgeoning North Vietnamese presence in the South.

The insertion of these main forces was at the heart of Hanoi’s strategy from the beginning. According to one Communist analysis, North Vietnam intended to “send individual regular main force units (battalions and regiments) from the North into South Vietnam and to form large main force armies on the battlefields of South Vietnam.” The use of these “very large and powerful military forces [would] create a fundamental change in the balance of forces between ourselves and the enemy.” The Communist leaders were particularly anxious “to completely defeat the puppet army before the U.S. armed forces had time to intervene.” Clearly, “classic” guerrilla war was not to be the Communists’ main vehicle for victory.

The Communist emphasis on main force combat changed everything in South Vietnam. Therefore, General Westmoreland, who took command of MACV in June 1964, would have been foolish to view the situation as purely an insurgency. As he wrote in his memoirs, “The enemy had committed big units and I ignored them at my peril.”

The Communist emphasis on main force combat changed everything in South Vietnam. Therefore, General Westmoreland, who took command of MACV in June 1964, would have been foolish to view the situation as purely an insurgency. As he wrote in his memoirs, “The enemy had committed big units and I ignored them at my peril.”

Westmoreland did understand the dual nature of the threat he faced, yet he believed that the enemy main forces were the most immediate problem. By way of analogy, he referred to them as “bully boys with crowbars” who were trying to tear down the house that was South Vietnam. The guerrillas and political cadre—which he called “termites”—could also destroy everything, but it would take them much longer to do it. So his attention turned first to the “bully boys,” whom he wanted to drive away from the “house.”

This thinking did not stem from a “conventional mindset” on the part of Westmoreland, but rather from his observations of the situation on the ground. On March 6, 1965, two days before the first U.S. Marines landed near Da Nang, Westmoreland sent a report to the Joint Chiefs of Staff warning that in some parts of South Vietnam “the Viet Cong hold the initiative” and the “deterioration process must be regarded as critical.” On the other hand, South Vietnamese forces were “on the defensive and pacification efforts have stopped.”

The only solution, he contended, was increased American intervention in order to stave off South Vietnam’s defeat. Westmoreland asked for more forces, and by the end of 1965 there were 184,300 U.S. troops in country. Although Westmoreland believed that he could “reestablish the military balance,” he cautioned the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, General Earle G. Wheeler, that reaching Washington’s objective of “convincing the DRV/VC they cannot win” was out of the question. The Communists are “too deeply committed to be influenced by anything but application of overpowering force.”

Despite the obvious need for immediate action to correct the dangerous course of events, Westmoreland understood that he faced a new kind of conflict. “There is no doubt whatsoever that the insurgency in South Vietnam must eventually be defeated among the people in the hamlets and towns,” he wrote in one of his planning documents. “However, in order to defeat the insurgency among the people, they must be provided security.”

This became the accepted course of action at the highest levels. During a meeting in Saigon in July 1965, the allies established the division of labor: The Americans would “stop and destroy units coming from DRV into South Vietnam,” while the South Vietnamese Army’s job was “to engage in pacification programs and to protect the population.”

It remains difficult to see why this plan has come to be regarded as controversial. Those who argue that there was a choice between two approaches—one that first sought to neutralize the enemy main forces, and one that would have instead emphasized counterinsurgency—ignore the stark realities on the ground. South Vietnam was on the verge of outright defeat. It was logical to place the strongest forces—the Americans—in a position to tackle enemy main force units, while the South Vietnamese—who had failed to deal with those very same main forces—turned their attention instead toward securing a population with whom they shared language and culture.

By many accounts, pacification—a term used in Vietnam for counterinsurgency—was all but ignored under Westmoreland’s command. The reality, however, was that it was Westmoreland who implemented many pacification programs and presided over ultimate reform in the effort. In September 1965, at the beginning of the U.S. troop buildup, Westmoreland wrote in a key directive that “the war in Vietnam is a political as well as a military war. . . . [T]he ultimate goal is to regain the loyalty and cooperation of the people, and to create conditions which permit the people to go about their normal lives in peace and security. . . .” The trick was to find a way to do this—and accomplish it in the face of increasing pressure from enemy main forces.

With considerable personal support from Westmoreland, the basic building block of the pacification program—the Civil Operations and Rural Development Support (CORDS) organization—was formed in May 1967. Under MACV, the military would take over what had been a divided and ineffective program run by civilian agencies in Saigon. While CORDS did not make great strides until the Communists’ hold over much of the countryside was lost after the 1968 Tet Offensive , all of the programs then used to good effect were begun under Westmoreland.

During 1965 and 1966 the Communists fought the Americans toe to toe, making little effort to act like guerrillas. Those years saw the largest percentage of attacks by battalion-size enemy units or larger—even greater than in the years of the two biggest enemy offensives of the war, 1968 and 1972. By spring 1967, the consensus among the Communist leadership was that the high-intensity main force campaign was unsuccessful, and thus the North Vietnamese shifted to a stand-off strategy. The enemy now rarely sought out battles with the Americans, and main force units either split up or faded into the jungles to await new developments. According to U.S. statistics for 1967, attacks by “small units”—usually defined as company size or smaller—totaled 1,484, a jump of more than 80 percent over the previous year.

Westmoreland’s strategy had worked in the sense that it pushed the enemy main forces away from the populated areas and temporarily took the initiative from the Communists. South Vietnam was preserved in the short term, though there was much more to be done. Yet despite early successes against the enemy, Westmoreland did not see that he had, in a way, been lucky. For almost two years the North Vietnamese followed a strategy that played to the American advantages of technology, mobility, and firepower. Once Hanoi backed away from main force attacks, its efforts were more successful. The main forces were still there, of course, and the Communists would use them again when the time was right.

But the ultimate symbol of American strategic failure, the Tet Offensive, was still to come. In late January 1968, the Communists attacked almost every major city and town; and, though all were pushed back and as many as 50,000 VC and NVA were killed, the offensive proved to be a huge political victory for the Communists. Despite more than two years of fighting, Westmoreland had failed to take and hold the initiative, and now the United States was running out of time.

In June 1968 General Creighton Abrams, Westmoreland’s deputy, took command of MACV. Historian Sorley argues that Abrams “brought to the post a radically different understanding of the nature of the war and how it ought to be prosecuted” and that he executed a “dramatic shift in concept of the nature and conduct” of operations, which Abrams called “one war.” Sorley ignores the heavy enemy losses suffered during the Tet Offensive, which allowed Abrams to operate with much less resistance than had been the case only a few months earlier. In October, Abrams reported, “There’s more freedom of movement throughout Vietnam today than there’s been since the start of the U.S. build up.” He attributed this to the weakened state of the enemy and predicted “This situation presents an opportunity for further offensive operations.”

Abrams moved the 1st Cavalry Division to the region west of Saigon, using the unit’s airmobility to run constant offensive operations along the border where it would “be in a good posture for pouncing on any new units coming over from Cambodia.” In I Corps he used the 101st Airborne Division in the A Shau Valley campaign in an attempt to prevent the North Vietnamese from moving men and materiel to the populated coastal regions. In the Central Highlands, the 4th Infantry Division continued its wide-ranging operations aimed at keeping the enemy back over the border. Indeed, many of Abrams’ operations could be called “search and destroy”—such as the large-unit sweep in May 1969 that included the controversial battle on “Hamburger Hill” in the A Shau Valley.

These operations paid off. “The enemy has made a major decision to shift his emphasis from the military to the political,” Abrams reported in November. “This decision was forced upon him by the enemy’s own recognition of his rapidly deteriorating military posture. . . .” The enemy’s “reduced military capabilities” gave the allies the perfect chance to “pull the rug” from under Communist attempts to reassert control over the population.

Indeed, Communist main forces were at such low ebb that in November Abrams launched the Accelerated Pacification Campaign, a three-month blitz to regain control of many of the villages lost during Tet. Such a plan, had it been tried in 1966, would have been impossible in the face of enemy main forces; but by late 1968 the Communists were hobbled enough that Abrams needed to use only a small percentage of his forces as a screen against large enemy attacks, putting the rest work supporting pacification.

When the Accelerated Pacification Campaign wound down at the end of January 1969, Communist control throughout South Vietnam had fallen from 17 to 12 percent. But in the end Abrams—just as Westmoreland—could not prevent the enemy main forces from returning, and no amount of pacification could change that.

As a new president entered the White House in January 1969, Richard M. Nixon brought with him new priorities, in particular a promise to extricate the nation from Vietnam. Negotiations with Hanoi were ongoing—if not productive—and the new administration placed a priority on training the South Vietnamese Army to stand alone while preparing to withdraw U.S. troops.

As Abrams adapted to the realities of fighting a war with diminishing manpower, he altered his tactics. Sorley contends that this represented a sea change in the war. “Tactically, the large-scale operations that typified earlier years now gave way to numerous smaller operations,” he writes.

In reality, U.S. operations differed little between Westmoreland and Abrams. Under both commanders the basic operating unit was the battalion, which was split into companies and platoons to patrol and search, coming together when contact with the enemy was made. For example, during the last quarter of 1965, the 1st Infantry Division, operating north and west of Saigon, conducted 2,919 operations with units smaller than a battalion and only 59 with larger forces.

Most other units recorded similar statistics. One study showed that between 1966 and 1968 there were “nearly 2 million Allied small unit operations” nationwide. Yet the preponderance of small patrols made no significant difference in the enemy’s overall ability to operate freely. Concluded the study: “Three-fourths of the battles are at the enemy’s choice of time, place, and duration.” That was true for Abrams as well as Westmoreland.

In the final analysis, the biggest difference Abrams faced was Vietnamization. Under the Nixon administration, the war was to be turned over to the South Vietnamese—to win or lose on their own. However, it was difficult to see how Saigon could maintain a steady emphasis on pacification and take on the mission of fighting Communist main forces. This was the same problem that had confronted the United States in 1964 on the eve of its entrance into the ground war, and it remained largely unresolved five years later.

Unfortunately, as the United States was withdrawing from Vietnam, the North Vietnamese were rebuilding. In early 1970, concluding that a pure guerrilla strategy would not achieve victory, Hanoi increased the combat power of North Vietnamese infantry divisions. Heavy artillery and armor was added, and by the end of 1971 the North Vietnamese Army had an overall strength of 433,000 men—up from about 390,000 in 1968.

As always, the Communists relied on their across-the-border base areas, but President Nixon was a much different war leader than his predecessor, and in 1970 he agreed to allow U.S. troops to invade the enemy sanctuaries in Cambodia—something for which both Westmoreland and Abrams had argued. In late April 1970, MACV received permission to launch a limited incursion into Cambodia, which brought about the razing of the North Vietnamese sanctuary.

A less successful incursion into Laos followed in February 1971. This time the South Vietnamese—without U.S. advisers—struck deep into the base areas and were ultimately driven out by North Vietnamese forces. While it was not a complete failure, the images of soldiers clinging to the skids of American helicopters gave the U.S. public an impression of defeat.

In the spring of 1972 Hanoi launched its biggest offensive of the war, a conventional combined arms assault against several targets throughout South Vietnam. More than nine divisions of infantry and armor attacked major South Vietnamese cities from the Demilitarized Zone southward to Saigon. Backed by U.S. air support, the South Vietnamese held.

General Abrams left Vietnam in June 1972, following his old boss General Westmoreland into the job of Army chief of staff. Both commanders had faced very different challenges and circumstances, but both had failed in the end.

America’s failure in Vietnam was partly a consequence of policy decisions—in particular allowing the enemy to maintain base areas in Laos and Cambodia (not to mention North Vietnam itself)—and South Vietnam’s ultimate flaws. But much of it stemmed from the Communists’ ability to hold the military and political initiative throughout most of the war. The strategy conducted by the North Vietnamese was arguably like no other in history: a combination of large main force units, a well-entrenched guerrilla movement with deep roots and the support of two powerful sponsors—China and the Soviet Union. All of this, combined with the ability to repeatedly attack South Vietnam with no threat of a serious retaliation, offered an unprecedented advantage.

Therefore, to simply argue that the U.S. military ignored counterinsurgency is unsatisfactory. Both Westmoreland and Abrams found themselves in a quandary: unless a significant part of their forces sought out the enemy main forces, there could be no security in South Vietnam. Therefore, the key to either general’s plan had to be the ability to keep the main forces away from the population; whether the operational method was called “search and destroy” or “one war” made little difference. Judged by that standard, both generals failed. Despite the progress made by pacification in the years 1967 through 1972, it made no significant difference in the end.

Indeed, both MACV commanders were caught on the horns of the same dilemma. While Westmoreland concentrated on the main forces and failed to prevent a guerrilla offensive in 1968, Abrams placed great emphasis on pacification and failed to prevent a conventional buildup in 1972. In the end neither commander had the resources or the opportunity to handle both threats simultaneously.

Even as the Vietnam War fades further into history, it continues to influence the U.S. military. General David H. Petraeus, the current chief of the Central Command and the former commander in Iraq, wrote in his doctoral dissertation, “The American Military and the Lessons of Vietnam,” that the war “planted in the minds of many in the military doubts about the ability of U.S. forces to conduct successful large-scale counterinsurgencies.”

But that is exactly what the United States again finds itself fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the comparison with Vietnam is inevitable. Unfortunately, the decades old debate over that war has only muddied the historical waters at a time when clarity is very much needed. Taking the wrong lessons from Vietnam will surely color how we wage counterinsurgency in the future.

Dale Andrade is a senior historian at the U.S. Army Center of Military History, where he is writing the Army’s official account of the Vietnam War between 1969 and 1973. The foregoing, which represents the author’s own opinions and not those of the U.S. government, is adapted from a journal article in the June 2008 Small Wars and Insurgencies. Andrade’s books include America’s Last Vietnam Battle: Halting Hanoi’s 1972 Easter Offensive, and, with Kenneth Conboy, Spies and Commandos: How America Lost the Secret War Against North Vietnam.