An ill-prepared British crew set out in 1922 on the first-ever attempt to fly around the world.

In August 1922, the crew of a steam launch plucked two exhausted and half-starved British airmen from the Bay of Bengal. The fliers had endured two interminable days clinging to the upturned floats of their capsized floatplane, which had been kept from sinking only by the air trapped in its empty fuel tanks. This minor epic of survival marked the untimely end of the first attempt to fly around the world—with only the first of four planned stages completed.

The flight was the brainchild of former World War I infantryman Major Wilfred T. Blake, who secured sponsorship from Britain’s Daily News and other backers. The patriotic Blake had heard a rumor that the Americans were planning a round-the-world flight and was determined to beat them to it. Ironically, his chance of being first had been improved by the tragic death of Australian aviator Ross Smith on April 13, 1922, while flight-testing the Vickers Viking amphibian in which he and his crew planned to attempt a circumnavigation. (Smith had already set the gold standard for contemporary long-distance flights in late 1919 by flying from Britain to Australia in a Vickers Vimy in 28 days—see “Off to Oz,” November 2009 issue.)

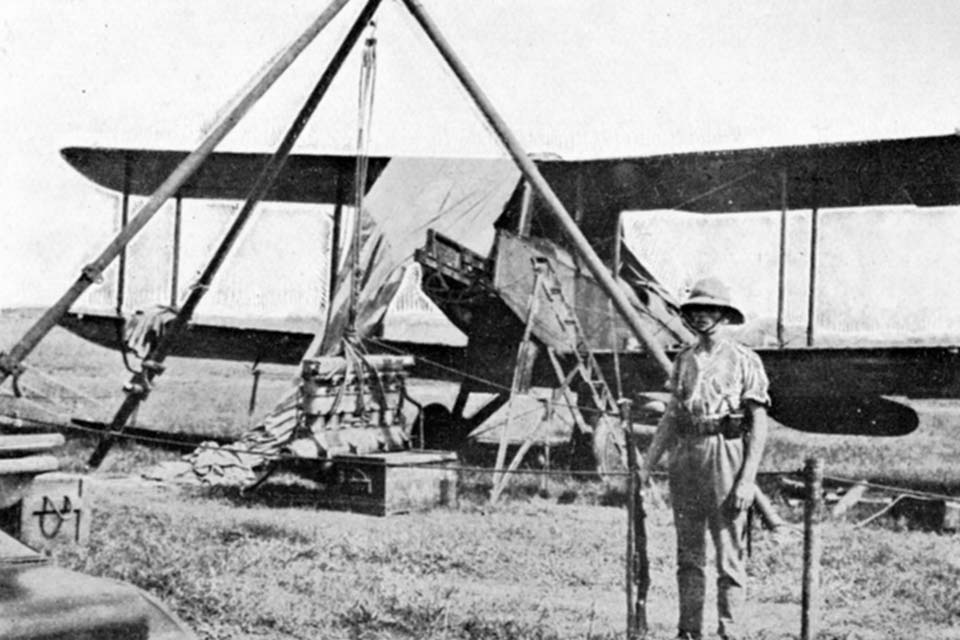

As his pilot, Blake recruited Captain Norman Macmillan, a test pilot and decorated nine-victory WWI fighter ace. A Far East expert, Lt. Col. L.E. Broome, and later Geoffrey Malins were to photograph the flight. Blake’s highly ambitious plan was to use a war-surplus Airco D.H.9 bought from the Aircraft Disposal Company (ADC), converted from two to three seats, for the London to Calcutta stage. A Fairey IIIC floatplane would undertake the demanding Calcutta to Vancouver stage, and then another D.H.9 would fly the long overland Vancouver to Montreal haul. After which, if all went according to plan, a Felixstowe F.3 flying boat would be used for the final stretch across Labrador, Greenland and Iceland to Britain. In total they aimed to fly 23,690 miles over the four stages.

Blake’s insistence on sticking to the announced departure date from London’s Croydon airport of May 24 meant that Macmillan had no opportunity to flight test the much-modified D.H.9 G-EBDE in fully loaded configuration with its enlarged fuel capacity. Indeed the ADC’s single flight test took place the evening before departure, and only then was the final coat of paint applied. Macmillan had particular concerns about G-EBDE’s all-up weight, not least because, as he said, “Broome weighs twice as much as Blake and I together.” There were also worries about the D.H.9’s 230-hp Siddeley Puma engine, which had proved unreliable in RAF service.

With good wishes from King George V, the trio departed Croydon on the afternoon of May 24, The New York Times reporting that “they hope to complete the journey in about ninety days, reaching Croydon on Sept. 7.” Moreover, Blake told a reporter that they “hoped to be on [North] American soil early in August.” But to many of those watching their departure, the D.H.9 “was extremely small and frail for such an ambitious flight.”

Once on course for the English Channel and France, Macmillan found that G-EBDE was tail-heavy, no doubt partly due to the heavyweight Broome in the rear cockpit. The pilot recalled, “I wound the control right back, but her tail still sagged in the air.” Three exhausting hours later, with muscles aching, he brought the D.H.9 into Le Bourget in Paris. Blake immediately telephoned the ADC to send over a mechanic to rectify the problem.

The delay cost them a day before they were airborne again, heading across the Alps to Turin. But clouds over the mountains and the overloaded G-EBDE’s lack of climbing power forced them to divert to Lyons and an unscheduled overnight stay. Weather conditions proving no better the next day, Macmillan headed for Nice, on the French Riviera, flying down the Rhône valley past Avignon. Running short of fuel, and with the Puma engine sounding ragged, he changed course for Marseille. Unable to locate the airfield, he force-landed the D.H.9 north of the city on the Parc Borely racecourse, damaging the undercarriage and smashing the propeller.

Next day the D.H.9 suffered further damage at the hands of careless French air force mechanics sent to dismantle and transport it to the Istres military flying school for repairs. Several frustrating weeks followed, during which efforts to restore G-EBDE to flying condition proved unsuccessful. Blake finally gave up and ordered another D.H.9 to be sent from England. To ensure photographic continuity, a dash of paint swiftly transformed the replacement G-EBDF into G-EBDE. On June 22, now well behind schedule, the flight resumed. By that time photographer Malins had replaced Broome, who departed to finalize arrangements in the Far East.

Their subsequent progress across France and Italy was beguilingly trouble-free. After an overnight stop in Rome, they flew past Naples and over the crater of Mount Vesuvius, where “Sulphur fumes stank in our nostrils.” To Blake’s alarm, the plane shot up 400 feet in the warm air and then dropped 600 feet. They continued on eastward, across the turbulent Apennines to Brindisi aerodrome, where another calamity awaited them. “A deep ditch, completely hidden in the long grass, tripped us up at the very end of the landing run and damaged the undercarriage and airscrew,” Macmillan recorded. Ten more days were lost waiting for a new prop to be sent from England, while the undercarriage was repaired with parts taken from an old Caproni. Meanwhile, Macmillan injured a foot in an automobile accident, so he had to fly the next stage wearing a carpet slipper.

After reaching Athens on July 6, the pilot needed to rest his injured foot for two days. Before the airmen departed, Queen Sophia of Greece presented them with provisions for the flight. They set a course across the Mediterranean for Crete and then Africa, settling down for what would prove to be their longest flight over water, landing 4½ hours later at the British military airstrip at Sollum, Egypt. Next day, after a slight delay due to a collapsed tailskid shock absorber, they flew along the Libyan Desert coastline to the RAF station at Aboukir, near Alexandria, arriving at dusk.

In the same casually optimistic spirit in which the whole flight had been undertaken, the trio had intended to fly from Aboukir into British-mandated Palestine and then, alone and unsupported, across the vast Syrian Desert to Baghdad. This route involved traversing more than 500 largely unmapped miles of an arid plateau rising up to 2,000 feet, with areas of dried-up wadis, mudflats and harsh basalt. The RAF would have none of it, however, stressing it was highly inadvisable for any civilian aircraft to fly that route unescorted. Moreover, they would be required to take food and water for five days, equivalent to the weight of an extra crew member. Instead the RAF obligingly arranged for them to travel to Baghdad in company with a radio-equipped Vickers Vernon transport, which would also carry their water. They were provided with desert sun helmets and rudimentary maps of the route, the navigation of which largely involved following the track made across the otherwise featureless desert by RAF armored cars in 1921, much easier said than done.

Predictably, G-EBDE’s eastward desert transit was far from incident-free. On July 11, having crossed Palestine, the crewmen joined their Vernon escort at Ziza, on the desert’s threshold. Flying low to keep the track in sight, they faced difficult flying conditions caused by the searing heat and intense glare from the ground. Stopping to refuel at RAF emergency landing grounds en route, they set out on their own after the Vernon developed engine trouble, eventually arriving parched and exhausted in Baghdad two days later. Along the way they had encountered friendly tribesmen who offered them goat’s milk to fill their radiator, as well as some others, less welcoming, who shot at them as they flew over. In the final stages of the desert crossing, the D.H.9 was so low on fuel that they force-landed and spent two hours transferring the last drops of petrol from the supplementary tanks to the main tank using a water bottle.

After two days’ rest in Baghdad, during which G-EBDE was thoroughly serviced by the RAF, the airmen flew south for three hours to RAF Shaibah, near Basra. There, in anticipation of even higher temperatures to come, the RAF soldered an additional cooling surface onto the D.H.9’s radiator. When they were airborne again on July 17, the engine remained cool, even if Macmillan did not. “Flying in the heat was hard work and I ran with perspiration,” he noted.

Heading southeast along the western shore of the Persian Gulf, the crew crossed the Persian frontier to touch down at Bushire. After refueling, G-EBDE set off again to fly the 400 miles to Bandar Abbas. Running out of daylight, Macmillan made a difficult forced landing on a sandy foreshore, where they dined on tinned lobster provided by Queen Sofia.

Arriving at Bandar Abbas early the next morning, they flew on to Chabar, their last airfield in Persia before reaching British imperial India. On July 19, after a five-hour flight along the coast, they were over Karachi, where Macmillan found “The green of the gardens and parks was a delight after arid lands.” For G-EBDE’s crew, it had been a relatively incident-free leg, in stark contrast to what was to follow, not least because their successive delays meant they had arrived in the monsoon season.

Their intended course across the Indian subcontinent had been via Nasirabad to Delhi and then south to Calcutta, where the Fairey IIIC floatplane G-EBDI awaited them for the transpacific stage. But since monsoon rains had flooded all the airfields along their planned route and an alternate route suggested by the RAF was soon ruled out by the overflowing Indus River, the crew decided to stage north through Jacobabad, or alternately Sibi. After that they would head northeast to Lahore, a diversion that would add many troublesome miles to their route.

Leaving Karachi on July 22, a four-hour flight along the Indus valley brought them to Jacobabad, where they had intended to refuel and then fly the 420 miles direct to Lahore. Unfortunately no fuel was available in Jacobabad, and so began yet another chapter of time-consuming misfortunes. Flying to Sibi, on the edge of the scorching Sind Desert, the airmen obtained a meager 12 gallons. They pressed on the next day to RAF Quetta, located on a high plateau 100 miles away, but found their route through the mountainous Bolan Pass shrouded in mist. Returning to Sibi, they damaged the tail skid and undercarriage on landing. Yet again the RAF came to the rescue, sending air and road parties to repair G-EBDE. Airborne once more on July 25, the trio had to turn back almost immediately with a fuel pump impeller malfunction. When the problem turned out to be beyond local repair, they had to fly to RAF Quetta, which they managed to reach only through the muscular efforts of Blake, laboring continuously on the emergency hand pump.

Three more days elapsed before they set off again for Lahore, stopping after five hours at Montgomery to refuel. Takeoff was delayed when a monsoon downpour turned the airfield into a quagmire, but somehow Macmillan managed to get G-EBDE unstuck, swerving between trees as the D.H.9 struggled to gain airspeed. “I felt the hot breath of the exhaust as we skidded under the leaves…,” he recalled. “That take-off was the most dangerous I have ever made….The skidding double bank at stalling speed brought her as near spinning as an aeroplane can get without crashing from such a low height.”

At Lahore, RAF mechanics repaired extensive broken stitching along the lower wing and fixed the mud-damaged prop. Heading next for Ambala, their course marked G-EBDE’s closest approach to the mighty Himalayas. In Ambala the RAF handed Blake a substantial bill for fuel and maintenance charges.

After further delays caused by contaminated fuel, and a forced landing on the Delhi racecourse, the airmen flew over the Taj Mahal to arrive in Agra on August 1. Originally on track for Allahabad, they had found their route blocked by a huge mushroom-shaped cloud and so force-landed at Agra, though only after flying through “a rush of water, like a waterfall.” On the ground the saturated fliers discovered that the D.H.9’s engine was beyond repair, with damaged pistons.

As the RAF had no Puma engines in India, it seemed like journey’s end. For once, however, luck was with them. They discovered that the air-minded maharajah of a nearby princely state had a private air force, known locally as the Bharatpur Flying Corps, that owned several war-surplus D.H.9s complete with spare engines. The amiable potentate instantly agreed to help, offering them one of his engines and all necessary technical support. It was nine days before Macmillan and Malins set off again in the refurbished D.H.9 on the final stage of its flight, transiting through Cawnpore, Allahabad and Gaya to Calcutta. Blake was no longer with them at that point; an attack of severe abdominal pain had forced him to travel by rail.

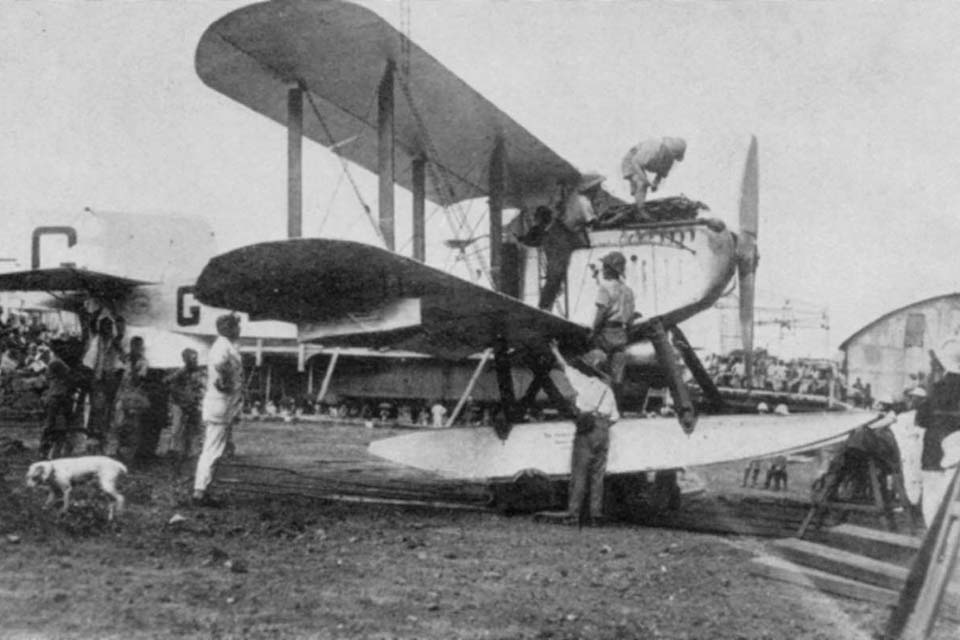

The three fliers were briefly reunited in Calcutta on August 12 before Blake entered the hospital with appendicitis. Meanwhile, G-EBDE was auctioned for 2,500 rupees to a Calcutta businessman. Macmillan and Malins set about inspecting and flight-testing the Fairey floatplane, which the RAF had reassembled after its shipment from England as deck cargo. Unfortunately, prolonged exposure to the elements had buckled the starboard float’s plywood covering. Additionally, the internal bulkheads of both floats were warped and rotten. Replacement floats were needed, but waiting for them to be sent from England would have meant postponing the flight until the following year, due to the impossibility of flying the difficult transpacific stage, via the Aleutians and Alaska to Vancouver, in winter. Refusing to give up, the two airmen improvised repairs using pitch, tar and caulking.

On August 19, braving atrocious monsoon weather, they took off from the Hugli River, intending to fly 320 miles southeast across the Bay of Bengal to Akyab, Burma. Defeated by 50-mph headwinds, they altered course to Chittagong, only to be forced down by an airlock in the fuel system. Taxiing to the island of Lukhidia Char, the two airmen spent a cramped night in the floatplane. The next morning they used teacups to bail out the waterlogged starboard float. By then a gale was blowing and they had to postpone taking off until the next day. Another uncomfortable night followed, curled up inside the airplane, with only a little food provided by locals. They awoke to 60-mph winds and rough seas, which meant spending a third night at Lukhidia Char.

Meanwhile, through an English-speaking local, they had managed to send a cable to Calcutta, giving their position and asking Chittagong to look out for them. Unfortunately, as events would show, it failed to convey a sufficient sense of urgency when read by the hospitalized Blake, who informed the Calcutta Statesman newspaper of the message but sent only an abridged version to Chittagong. As an angry Macmillan later recorded, it was couched “in words as nonchalant as if two airmen (who had been missing for four days) might be taking the London tube from Richmond to Victoria.”

Airborne once more on August 22, the fliers were quickly forced down again due to water in the fuel system, and an attempt to taxi to Chittagong was abandoned after their fuel ran out. Soon the defective float again became waterlogged, this time with disastrous consequences. The Fairey capsized, remaining afloat only through the air trapped in its empty fuel tanks.

Summoning up their last reserves, Macmillan and Malins clung to the floats for two long days and nights before they were rescued by Chittagong’s harbormaster, Commander J.C. Cumming, in the steam launch Dorothea. Cumming had read the full account of Macmillan’s cable in the Calcutta Statesman and, comprehending the urgency of the situation, organized an immediate search. The harbormaster later recalled of the airmen, “They were in a very bad state and almost exhausted, tongues swollen and skins turned black by the sun and their feet so badly swollen from contact with salt water that they could scarcely walk, and both had high fever.” An attempt to tow the floatplane soon had to be abandoned due to heavy seas.

Taken to the hospital in Chittagong, Macmillan and Malins spent the next few days recovering. In the 91 days since departing Croydon they had, through the flight’s numerous diversions and technical problems, covered many hundreds more miles than Blake’s anticipated 6,352 miles for the first stage. Yet G-EBDE was not even the first single-engine aircraft to fly from England across the Indian subcontinent, a distinction that belonged to Australians Ray Purer and John McIntosh for their epic 206-day flight in a D.H.9 to Australia in 1920.

Aeroplane magazine, which ran a satirical cartoon on the flight’s early stages, scoffed at their efforts: “It was foredoomed to failure, and for that reason this paper from the beginning refused to take it seriously.” Of course, the magazine was not alone in that view. But while Aeroplane and other doomsayers were proved right, and the flight had been unquestionably ill-conceived and logistically haphazard, the airmen deserved great credit for their unflinching determination in battling the worst that the weather and the mechanical quirkiness of early aircraft could hand them.

Years later, Macmillan indulged in some wishful hindsight when he wrote, “Cumming saved our lives, but the delay in his receiving our full message lost us the floatplane and ended our attempt to be the first to fly round the world.” Given the generally poor condition of the Fairey IIIC at the start of its flight and the additional harm done to the floats and engine in the Bay of Bengal, it is hard to imagine that, even if the floatplane had been taken securely in tow before it capsized, it could have been restored to flying condition for the arduous transpacific stage before winter set in. Blake’s original plan had envisaged reaching North America in early August.

Blake and Macmillan’s heavy reliance on the RAF for crucial technical support during the Middle Eastern and Indian legs was not forgotten by Air Ministry officials. When in 1924 Squadron Leader Archibald MacLaren proposed flying around the world in a Vickers Vulture amphibian, he was cautioned: “A world flight in which the Air Ministry is in any way involved must succeed, or a tremendous loss of prestige will result….The recent attempt of Blake did immense harm to the cause of aviation in India and the East, and we cannot risk another failure.” (See “All in the Game,” September 2010.)

It would remain for a team of U.S. Army Air Service aviators, flying in purpose-built Douglas World Cruisers, to finally complete the first aerial circumnavigation during 1924. But that’s another story.

RAF veteran Derek O’Connor, who writes from Amersham, Bucks, UK, is a frequent contributor on British aviation topics. For further reading, he recommends: Freelance Pilot and Wings of Fate, both by Norman Macmillan; and Flying Round the World, by Major W.T. Blake.

This feature originally appeared in the January 2014 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.