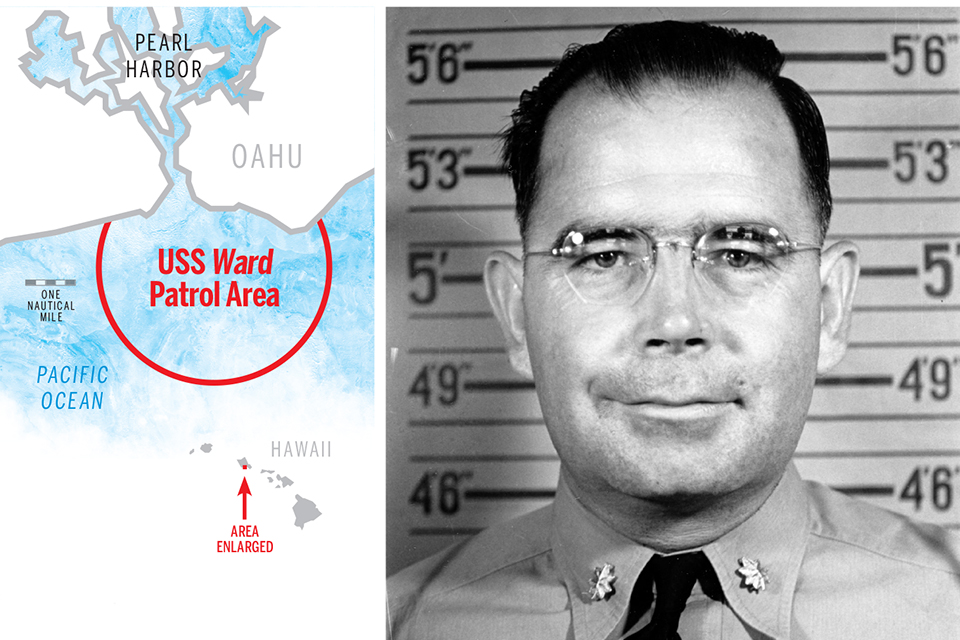

With the dawn of December 6, 1941—the 8,426th consecutive day of peace in America—the venerable USS Ward took in its lines and began slipping through the sedate waters of Pearl Harbor, bound for the channel and, unknowingly, history. The ship had been given an unglamorous duty, a destroyer’s lot. It was to carve lazy laps offshore, east to west and back, not even out of sight of Oahu, a sentinel primed to challenge any unknown vessel on or below the surface that inched toward the den of the U.S. Pacific Fleet.

However prosaic the mission, the Ward’s leader could hardly have been happier. Stuck as a number two serving a captain he loathed on another destroyer, the Cummings, a week before, Lieutenant William W. Outerbridge had taken command of his new assignment less than a day earlier. “These boys on here don’t know how strange it is to me to be called ‘captain,’” the lieutenant wrote to his wife, Grace, “but it is music to my ears.”

Outerbridge’s successor, as executive officer of the Cummings, had not only been named, but reported for his new assignment sooner than expected. Outerbridge was free at last, in time to take the Ward on a scheduled patrol. “December is my lucky month,” he continued. “I got a good ship, and the best wife in the world.”

In another letter he said he hoped to measure up as a destroyer captain.

He would, very shortly.

Just a week prior, Outerbridge’s overriding goal was to find any way to get transferred off the Cummings and be done forever with his captain, the “nasty, suspicious” Lieutenant Commander George Dudley Cooper, or “Dud,” as Outerbridge called him. Dud was “a small person,” he told Grace earlier that month. Dud was “an ass.” Dud was “the devil.” His rules were arbitrary, his paranoia great.

With a slight build, glasses, and big ears, Outerbridge, 35, was hardly a prepossessing figure. In a photo of a group of officers taken some time later, he appears in the front row, knees and feet jammed together, hands tucked between thighs, shoulders pulled in, the absolute model of diffidence. It is as if a shy history teacher is not sure he belongs in the navy. But Outerbridge had backbone enough to relentlessly argue with Cooper. His contempt for him was so sizable and obvious that Outerbridge was actually looking forward to getting his tonsils out, which had become a medical necessity. “It would tickle me if the ship got under way while I was in the Hosp.,” he wrote his wife.

The best solution to the Cooper problem would be a shore assignment, anywhere. And Outerbridge was trying. “Hope someone in the [personnel] bureau decides that we have had enough sea duty and also that we should be promoted,” he wrote on November 18. A billet at a naval base would mean family reunification. Outerbridge missed his three little boys back on Jackdaw Street in San Diego. “I wish I could be there to raise them more personally, as I feel they have the makings of good men,” he wrote. He missed Grace. He felt that the two of them seemed to be entering a good phase of life—older and wiser. “I only wish that we could be together more,” he told her, “but our time will come.”

As a military family, they had a military family’s financial worries. Outerbridge made $356 a month, which meant that the recent but necessary purchases of a new car and a washing machine in San Diego had drained so much from their bank account that they would have to hold back on any further large expenditures.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

He had made sure, however, that Grace and the boys would be all right financially without him, and he explained why. “If I am killed, you will get immediately by wire $1,500 from Navy Mutual Aid and $1,500 from the Treasury Dept. as gratuity, 6 mos. pay,” he told Grace. “I have made provisions for the amount of the policy of Mutual Life, N.Y. ($5,000.00) to be held in reserve for emergency or education of the children. It will be payable on demand.” He outlined some other smaller payments she would get as well. “This is all in case I die this year.”

Death was certainly possible. Outerbridge was only a junior officer on a small ship in a fleet that contained more than 100 vessels, and he was not privy to top-level correspondence or included in meetings with the commander in chief. And he was unaware that on November 27 the navy had issued a “war warning,” sparked by knowledge of Japanese forces on the move. But Outerbridge read the newspapers. He listened to local radio. He heard the talk. A clash with Japan seemed so close now, he thought, that it might interfere with his tonsillectomy. That evening, he wrote Grace that if nothing big happened, he would head to the hospital on Monday, December 1. “I wonder what the Japs are going to do now,” he said.

Then, soon after—without the slightest hint or hope that he would be free of the detestable Captain Cooper so beautifully soon—Outerbridge’s crusade to get off the Cummings ended in victory. Someone, somewhere, in the navy bureaucracy read his request for a transfer and decided Outerbridge was ready to immediately command a ship, specifically the destroyer Ward. His tonsils had a stay of execution. They would not come out on December 1, as he had planned. There was too much to do.

The Ward was hardly a prized stallion. Its hull had first touched the water on June 1, 1918, at the Mare Island Naval Shipyard near San Francisco. Because Outerbridge had served aboard two of its identical four-smokestack sisters, Ward’s silhouette, size, and passageways were as familiar to him as old shoes. “Being on one of these old cans seems like old times,” he said.

“I was particularly impressed with the spirit of the crew,” Outerbridge wrote. “They are almost all reserves, but are very much alive and full of pep. They seem to be much above average.” He added: “Hope I can have a happy, hard working, and efficient ship. I can’t tell you much about how it feels to be captain, but so far it is very fine.”

His new home was not assigned to the Pacific Fleet but to Oahu’s 14th Naval District, for close-in submarine patrol around the island. His days of extremely long cruises on the rollicking, open seas were over for now, which was fine by him. His stomach never did get used to the choppy waters, which were a part of being a career naval officer. The new job entitled him to quarters ashore.

It might even be a brand-new dwelling, given how much building was under way in and around Pearl, he thought. Grace and the three boys could come out. They would be a family again. Outerbridge assured her that any house would be near a school, as well as “near the commissary, near the gas station, near the ships service store, near the hospital and not far from town,” he stated, as if trying to convince his wife that Oahu was modern and American, and not some misty, primitive isle of the sort found in National Geographic.

“The mess of moving and getting settled is something, but I am sure that you will enjoy living out here,” he told her. “It is expensive but everyone enjoys the climate, and I feel that we will be happy.” If she got lucky with a booking, she and the boys could arrive aboard a Matson liner after Christmas. He had already shipped holiday packages with gifts, he said. “If Japan just stays quiet, we shall have a very happy sojourn on the island.”

Twenty-four hours into his first patrol, Outerbridge fell asleep on a cot in the chart room near the Ward’s bridge. The night had been fitful. Shortly before 4:00 a.m., a navy minesweeper, the Condor, had reported a periscope seen off the harbor entrance. The Ward had gone to inspect, but had found nothing and resumed its back-and-forth patrol. Now, at 6:37 a.m., a cry penetrated Outerbridge’s unconsciousness—“Captain, come on the bridge!” It was a summons he knew heralded something out of the ordinary.

The sun was 10 minutes up. December 7 was going to be mild and partly cloudy.

Slipping on his glasses and robe—a kimono—Outerbridge reached the bridge to find the helmsman and several other men staring at a black object barely poking out of the water, approximately 700 yards ahead. Off to port was a navy cargo ship, the Antares, towing a barge on a long line and headed into the harbor. The moving object appeared to be sneaking between the Antares and its tow, as if hoping to draft in the wake of the hauler.

A conning tower.

And not shaped like an American one.

Outerbridge was new to his job, but he knew exactly what to do. “One look he gave,” the helmsman, H. E. Raenbig, later said, “and [he] called General Quarters.” Gun crews galloped toward their mounts, the crew sealed doors and hatches, a demand for ahead-full descended to the engine room, and the Ward shot forward, climbing from five knots to 25, setting a course to get between the Antares and the intruder—a near ramming speed.

The submarine, which bore no markings, was oblivious to the destroyer’s rapid closure. It was a mere 80 feet long, Outerbridge estimated, a miniature version of the norm—a rusted, mossy oval plagued by barnacles, both its bow and stern awash as it plowed ahead. The sub appeared to have no deck guns. The crew of the Ward was unaware they were bearing down on one of a handful of tiny submarines the Imperial Navy hoped to sneak into the harbor.

A less confident captain would have doubted this really could be the Japanese in the waters near Oahu and the end of peace. Outerbridge told his boys to fire away. At 100 yards, as the Ward cut across the enemy’s path, the forward four-inch gun spit, the shell roaring over the little vessel and into the sea beyond. At 50 yards, with the midget sub directly to starboard, the Ward’s number three four-inch gun amidships fired, punching a hole in the conning tower at the water line. The mini recoiled. As the Ward’s momentum took it past the sub, it “appeared to slow and sink,” Outerbridge said, the Japanese vessel submerging through the destroyer’s wake. Four depth charges rolled off the Ward’s stern were set to explode at 100 feet, and they did. “My opinion is that the submarine waded directly into our first charge,” said W. C. Maskzawilz, the enlisted man who dropped the explosives.

The destroyer came about and retraced its path. An oil slick bloomed on the sea. Sound detection equipment heard nothing from below.

Only a few minutes had slipped by. The Ward had fired the first shots of the American war in the Pacific. Quickly Outerbridge wrote, encoded, and radioed a message to Pearl: “We have dropped depth charges upon subs operating in defensive sea area.” Then he reconsidered. The phrasing might suggest they had responded only to vague, underwater sound contacts, when they had seen an actual submarine on the surface. They had shelled it and hit it. It was there. There was oil on the water. Two minutes later, Outerbridge sent a second message, more precise and more alarming. “We have attacked, fired upon, and dropped depth charges on a submarine operating in defensive sea area.”

Fired upon.

Outerbridge wanted to be absolutely certain he was clearly heard and understood.

“Did you get that last message?” he radioed.

His report left the ship at 6:54 a.m. Outerbridge had been sent out to be on guard, and he had been. The new captain and the old Ward had just provided Pearl with a chance.

Outerbridge’s message crawled up the chains of two navy commands, the 14th Naval District and Pacific Fleet. On the District side, to which the Ward belonged, there was skepticism. The chief of staff, Captain John B. Earle, had the impression “it was just another one of these false reports which had been coming in, off and on.” He called Admiral Claude C. Bloch, the District commandant, who asked, “Is it a correct report, or is it another false report? Because we had got them before.” Earle ordered the on-call destroyer, the Monaghan, to head out and join the Ward, just in case.

Commander Vincent R. Murphy, the fleet’s duty officer, learned second-hand of the Ward’s report at about 7:20 a.m. as he was getting dressed at home. He wanted details, such as whether there had been some sort of chase before the destroyer fired, but the telephone line to the officer who had taken Outerbridge’s message was busy. Murphy went to fleet headquarters, where his regular job was assistant war plans officer, and where he finally got through to the man who had Outerbridge’s initial report. Murphy then called Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, commander in chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. The time was approximately 7:40 a.m., almost 46 minutes after Outerbridge had radioed that the Ward had opened fire.

Kimmel told Murphy he was coming to the office, but he issued no orders. “I was not at all certain that this was a real attack,” Kimmel said of Outerbridge’s report. A few minutes later, the duty officer called the admiral back to say the Ward filed a second message about having detained a sampan.

Suddenly a yeoman burst into Murphy’s office: “There’s a message from the signal tower saying the Japanese are attacking Pearl Harbor, and this is no drill.”

Murphy related this to Kimmel on the phone. It was just before 8:00 a.m.

In the days following the attack, perhaps the happiest man on Oahu was Lieutenant William W. Outerbridge. “Joined the ship Friday, got under way Saturday morning, and started the war on Sunday,” he said to his wife, Grace, in a letter that would not reach her in San Diego for days. “The Ward has a fine reputation now.” The destroyer was being called the “Watchdog of Pearl Harbor,” he said, even if its vigilance had turned out to be only another “what if” in the painful saga. “Have had the time of my life,” Outerbridge wrote, somewhat insensitively considering what had happened. “This life has its compensations.”

Outerbridge did not realize Grace had no idea whether he was still alive. In the naval community of San Diego, many wives were not immediately made aware of their spouse’s fate.

“Really, the atmosphere around here is ghastly,” Grace wrote to her husband, hoping he would receive the letter. The next day, she wrote, “Don’t know how much longer I can stand it.” Shortly after, the casualty lists came out. “I haven’t been notified,” Grace wrote him, “so I’m sure you must be alright.” But even that hard data did not douse her anxiety. “Would give anything to know where you are, and what you’re doing.” Nearly a week after the attack, a telegram finally arrived, and Grace hesitated for several moments before opening it only to find five words.

Well and happy, William Outerbridge.

“I was so relieved, I sat down and bawled,” Grace wrote back, “and then I fixed myself a drink, and drank it while I sat at the phone and called up all the folks who have been inquiring about you.”

Outerbridge and the Ward parted company in 1942, only to be reunited later in the war in surreal fashion. While the Ward was escorting a convoy near the Philippines, Japanese bombers set upon it, one of them crashing into its starboard side at the water line and exploding. With fires raging, and having no water pressure with which to fight them, the crew abandoned ship. Rather than leave a hulk adrift, the nearby destroyer O’Brien was ordered to sink the Ward with gunfire. The old destroyer went down on the morning of December 7, 1944—three years to the day after it had warned Pearl Harbor.

The captain of the O’Brien was Commander William W. Outerbridge. ✯

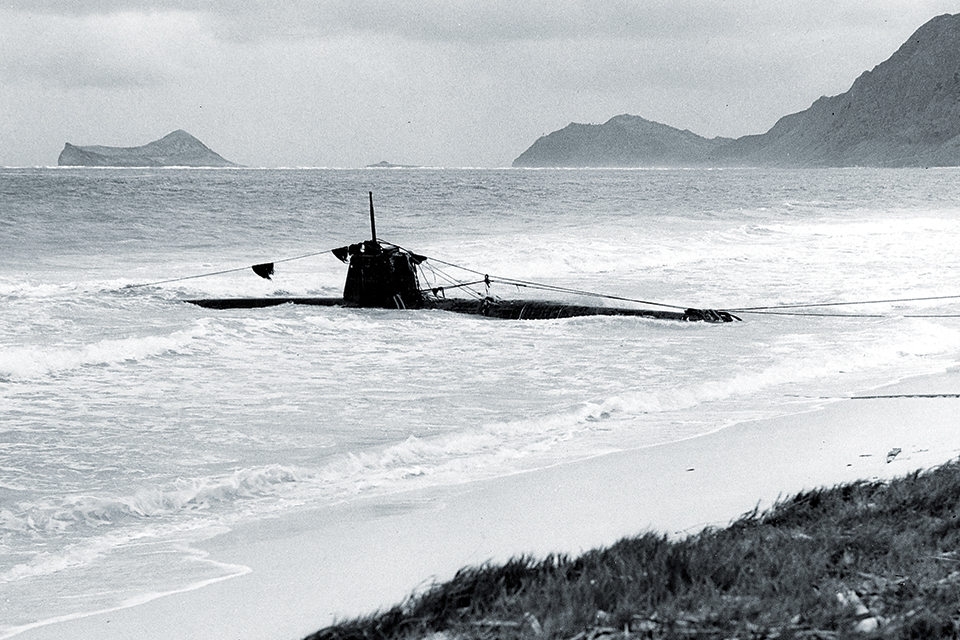

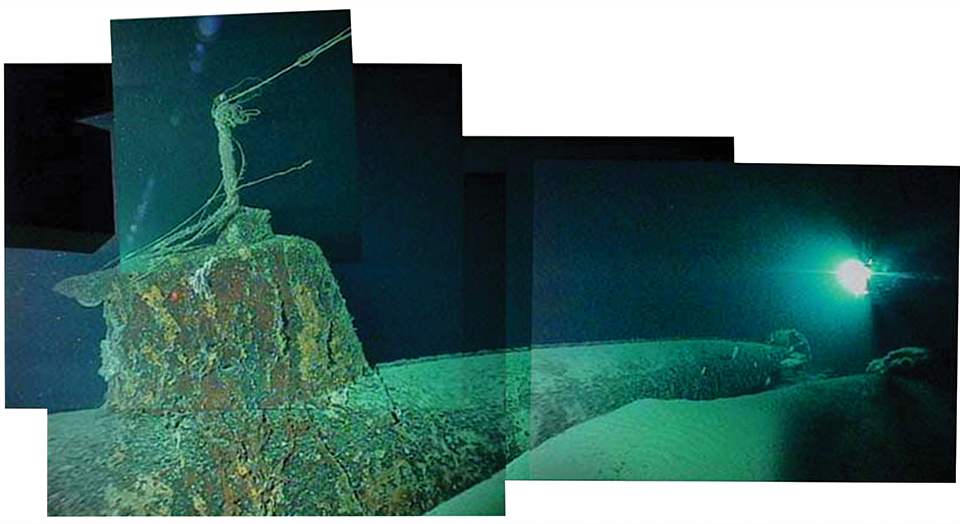

Proof Positive

For more than 60 years after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the USS Ward’s crew had their doubters. If they had sunk a Japanese sub, where was it? Even famed undersea explorer Robert Ballard came up empty in a 2000 search. Then in 2002 a team of scientists on a routine mission in two submersibles discovered the midget sub 1,200 feet underwater, some three miles south of the harbor. Its hatch was closed, its two torpedoes retained—and its conning tower had a shell hole. Terry Kerby, pilot of one of the submersibles, called it a “sobering moment, realizing that was the shot that started the Pacific War.” ✯