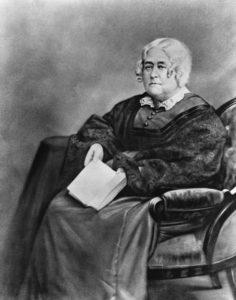

Boston spinster who introduced kindergarten was an editor, publisher, and literary gadfly

IN HIS 1886 novel, The Bostonians, Henry James describes one character, Miss Birdseye, an elderly reformer, as having “a dingy, loosely-habited air, as if she had worn her clothes for many years and yet was even now imperfectly acquainted with them; a large, benignant face, caged in by the glass of her spectacles, which seemed to cover it almost equally everywhere, and a fat, rusty satchel, which hung low at her side, as if it wearied her to carry it.” Many historically minded readers believe that James based Miss Birdseye on Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, who made a name for herself as what one scholar called a “practical intellectual.” Known as a teacher, writer, publisher, editor, bookstore proprietor, and activist, Peabody is often remembered less for what she did than for who she knew. And she seemed to know everyone who was anyone.

No image remains of slight, blue-eyed Elizabeth Peabody as a young adult, when she was pioneering her unusual brand of celebrity in 1820s Boston literary circles. Peabody in 1830 was the first

to hold salons for women; first to translate portions of the Buddhist text Lotus Sutra from French into English, in 1843; first to publish, in 1849, her friend Henry David Thoreau’s essay “On Civil Disobedience”; and, in 1860, the first proprietor in Boston of kindergartens, which quickly became a nationwide phenomenon.

Acquaintances sometimes described Peabody, the oldest of eight children, as disheveled or disorganized, pouring her prodigious energy into understanding herself and the world. In 1813, Elizabeth, age nine, became enthralled with William Channing, an unprepossessing minister who gave homilies so riveting he made Unitarianism fashionable. She subsequently served for nine years, unpaid, as Channing’s secretary. At age 13, intent on persuading her parents that she could make up her own mind on religious matters, Peabody read the New Testament 30 times in the course of a summer. Later, with friends, she created a reading circle in which she challenged arguments made by Martin Luther and William Penn.

Her father was a physician whose income was irregular. By 17, his eldest child was running a school for younger girls, and by 22 had relocated five times around New England to teach. Each time, Elizabeth improved her situation—out of necessity, since she now often was shouldering much of the responsibility for sustaining her family.

In 19th-century America, teaching school was the default occupation for a literate single woman, and Peabody, who burned with passion for learning, had grown up with a mother who taught—not only a role model but a mentor. Able to read half a dozen languages, Peabody tutored students in what amounted to a private school. Her intellect brought her friendships with philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson, educator Bronson Alcott, legislator and educator Horace Mann, writer Nathaniel Hawthorne, and other kindred spirits. Her sisters Mary and Sophia won the hearts of suitors initially drawn to their older sibling. Mary married Horace Mann, and invalid artist Sophia wed the beautiful Hawthorne, whose writings Elizabeth championed.

Their circle’s tangled emotions power Megan Marshall’s 2005 The Peabody Sisters, a bestselling biography. Peabody knew talent and served friends as an encouraging critic, but her greatest legacy is her popularization in the United States of kindergarten, an early childhood teaching method adopted from the work of a German scholar. But that undertaking would come late in a long life of loving books and ideas.

Deeply religious, Peabody hung out with Emersonian Transcendentalists, exploring Christianity and the nature of individual freedom and authority. She was a quester whose interest in historical events ran in tandem with her literary and religious interests. Wanting to reach beyond rote learning—and keenly aware of the power of story to interest students—she incorporated biography into her educational technique. In 1830, by organizing “reading parties” for women in which she directed conversations about history, Peabody broke ground as the first woman lecturer. She published history texts aimed at female readers. Scholars at Harvard relied on her for translations of historical works, which she delivered at no charge. Her translation of writings by French philosopher Baron Joseph-Marie de Gérando influenced Emerson’s 1841 essay, “Self-Reliance.”

In 1839, Peabody stepped out of the classroom and opened West Street Bookstore near Boston Common. She and family members lived upstairs. The store drew local intelligentsia, such as pioneering feminist critic Margaret Fuller and author Thomas Wentworth Higginson. Peabody briefly was publisher of The Dial, a Transcendentalist periodical. Aesthetics, a volume she edited, introduced Henry David Thoreau’s “On Civil Disobedience.”

Whether due to uneven employment or her brothers’ unstable fortunes, Peabody’s finances were always precarious. In the late 1840s, ever enterprising, she worked up a salable educational product: an early form of interactive learning. The idea was to have students chart centuries of history, indicating countries by color and events by shape. The result had a quilt-like vibrancy. Peabody spent a few years peddling her method to educators nationwide. She also incorporated it into an 1856 book, Chronological History of the United States, but the color-coded charting technique never caught on.

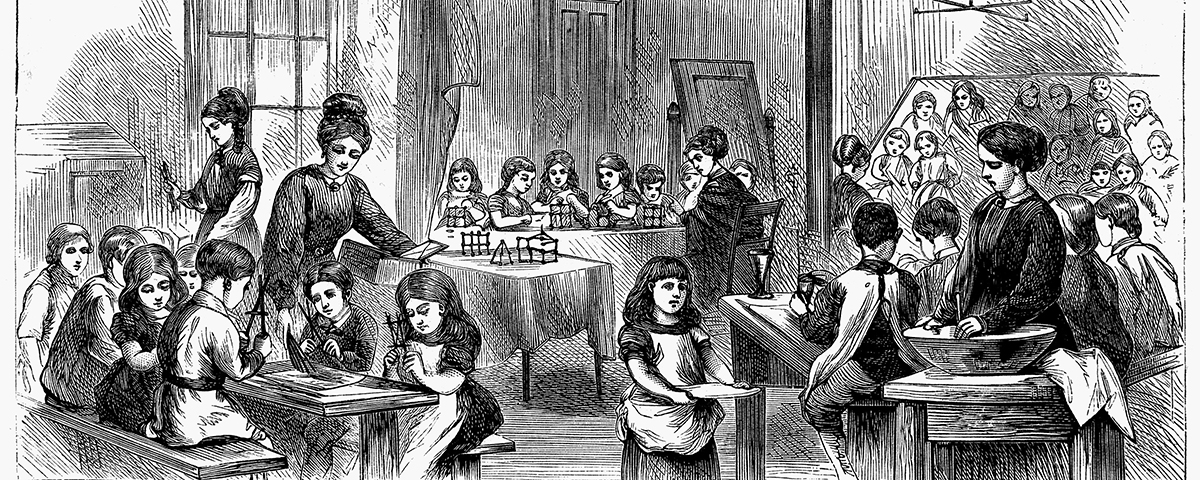

Peabody shifted professional direction in 1859 when she met an adherent of Friedrich Froebel, a German educator who combined the German words for “children” and “garden” to name his method of early childhood instruction Kindergarten. In Watertown, Wisconsin, Margarethe Schurz had established a German-speaking kindergarten. Intrigued, Peabody adapted the approach to English and in Boston began a new chapter in American education: the cultivation of young minds in a setting that promoted creative play. She even traveled to Germany in 1867 to learn more and encouraged teachers trained under Froebel to come to America.

Peabody earned her greatest fame as a champion of realizing children’s potential through organized play, founding the monthly journal Kindergarten Messenger in 1873. However, that devotion had a cost, literary acquaintance Moncure Conway said: “She had a larger circle of friends than any other one person, and she should write of ‘The Men and Women I have Known’: it would be a literary history of her time, unsurpassed in interest. Instead, she is spending her energy and time in going about speaking for the kindergarten. It is a loss to literature.”

But Peabody picked her own projects, including ardently supporting in the 1880s Sarah Winnemucca, a Paiute committed to educating her tribe in ways respectful of tradition. Peabody drew barbs for unrelenting advocacy on behalf of the disadvantaged, but T.W. Higginson saw his friend in a wider context, calling Peabody “desultory, dreamy, but insatiable in her love for knowledge and for helping others to it.” Her gravestone at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Concord, Massachusetts, notes: Every humane cause had her sympathy, and many her direct aid.

Peabody never married; late in life she and widowed sister Mary shared a home described as “high thinking and plain living,” with a backyard tent village housing poor immigrants and others down on their luck. After her death in 1894, friends established Boston’s Peabody House, a center for educating needy immigrants and children that celebrated its 121st anniversary in 2017 at its location in Somerville, Massachusetts.