In the 140 years since the Lincoln assassination, innumerable myths, legends and astonishing statements have been circulated about the ‘crime of the century.’ One of the latter featured the type of clever word game that Americans have long relished: Booth saved Lincoln’s life. The statement is true, but the incident to which it refers did not involve President Abraham Lincoln and his assassin, John Wilkes Booth. Instead it refers to Edwin Booth, John Wilkes’ older brother, and Robert Todd Lincoln, the president’s only child to reach maturity. Just as intriguing as the suggestion imbedded in the word game, however, is the episode’s transformation as it appeared in publications from 1893 to 1979.

Robert Todd Lincoln was the eldest of Abraham and Mary Lincoln’s four sons. A 17-year-old student at Harvard when the Civil War began, he spent the majority of the war years at college. Much to the embarrassment of the president, his mother refused to allow him to enlist. In February 1865, Robert joined General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant’s staff as a captain and assistant adjutant general of volunteers. He stayed with Grant until the end of the war, accompanying him to Washington on April 13, 1865. The next day he spent two hours with his father, telling him of his experiences in the army, which included witnessing Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House. That night, he chose not to accompany his parents to Ford’s Theatre to watch a production of Our American Cousin. It was a decision he soon came to regret.

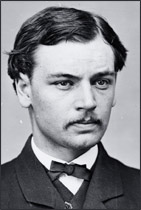

Edwin Booth, born in 1833, was the second oldest of Junius Brutus Booth’s three sons. Junius was considered by many to be among the finest Shakespearean actors of his day. While John Wilkes was a competent actor who played to good reviews, Edwin was also regarded as one of the 19th century’s great Shakespearean actors. His most famous part was Hamlet, which he portrayed more often than any other actor before or since, including a run of 100 consecutive nights. In 1862 Edwin became manager of the Winter Garden Theatre in New York City, where he presented highly acclaimed Shakespearean productions.

|

| Robert Todd Lincoln, the first child born to President Abraham Lincoln and Mary Todd Lincoln, spent most of the war years at Harvard College but joined General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant’s staff early in 1865. (Library of Congress) |

But Edwin and his brother John were not close, chiefly because Edwin was a Unionist and Lincoln supporter while John was a rabid secessionist. Edwin once wrote of his brother: That he was insane on that one point [secession] no one who knew him well can doubt. When I told him that I had voted for Lincoln’s reelection he expressed deep regret, and declared his belief that Lincoln would be made king of America; and this, I believe, drove him beyond the limits of reason.

Fate brought Lincoln and Booth together in a train station in Jersey City, N.J., in the midst of the Civil War. At the time Robert was on a holiday from Harvard, traveling from New York to Washington, D.C., while Booth was on his way to Richmond, Va., with his friend, John T. Ford (owner of Ford’s Theatre in Washington). The exact date of the encounter is unknown, although Robert consistently recalled it as having occurred in 1863 or 1864.

Robert Lincoln wrote the most succinct account of the incident in a 1909 letter to Richard Watson Gilder, editor of The Century Magazine, who asked him to verify that the episode actually took place:

The incident occurred while a group of passengers were late at night purchasing their sleeping car places from the conductor who stood on the station platform at the entrance of the car. The platform was about the height of the car floor, and there was of course a narrow space between the platform and the car body. There was some crowding, and I happened to be pressed by it against the car body while waiting my turn. In this situation the train began to move, and by the motion I was twisted off my feet, and had dropped somewhat, with feet downward, into the open space, and was personally helpless, when my coat collar was vigorously seized and I was quickly pulled up and out to a secure footing on the platform. Upon turning to thank my rescuer I saw it was Edwin Booth, whose face was of course well known to me, and I expressed my gratitude to him, and in doing so, called him by name.

Months after the incident, in 1865, Booth received a letter from a friend, Colonel Adam Badeau, then serving as an officer on Grant’s staff. Lincoln had related the story of the rescue to Badeau while they were stationed at City Point, Va., and Badeau supposedly offered Booth his compliments for having performed such a deed.

According to one Booth biographer, Robert’s superior, Ulysses S. Grant, also wrote to Booth to congratulate him on his heroism. Grant not only praised Booth’s quick actions but also said that if he could ever serve Edwin, he would gladly do so. Edwin reportedly replied that when Grant was in Richmond, the actor would perform for him there.

While the rescue clearly seemed significant to Robert at the time, there is no existing evidence that he ever told his parents about it. This may not be too surprising, given that he and his father were not particularly close. The president, Robert may have assumed, had enough worries.

|

| Edwin Booth, older brother of John Wilkes Booth and son of actor Junius Brutus Booth, was considered one of the great American Shakespearean actors of the 19th century. (Library of Congress) |

Perhaps the eldest son also feared his mother’s reaction to the story. Mary Lincoln was a fragile, even unstable, woman, especially after the death of the Lincolns’ third son, Willie, in 1862. In fact, Mary had some hysterical episodes even when Robert was little. When the boy was about 3 years old, he went out to the family privy and put some lime in his mouth. Mary, terrified, ran out into the street screaming, Bobbie will die! Bobbie will die! Neighbors came to the rescue and soon washed out the boy’s mouth.

On the evening of Good Friday, April 14, 1865, Robert was at the White House visiting with his friend John Hay, the president’s private secretary. When Robert heard that his father had been shot, he rushed to the Peterson house, where his father had been carried, and remained until the president died.

Robert Lincoln’s life was apparently forever darkened by that night, not only by the loss but also by the belief that he might have saved his father’s life if he had attended the play. His close friend in later years, Nicholas Murray Butler, recounted in his memoir that the president’s son never forgave himself for his absence. As the youngest member of the presidential party, Robert would have sat at the back of the box, closest to the door. He reportedly told Butler that, had he been present, Booth would have had to deal with him before he could have shot the president.

|

| Edwin Booth as Hamlet circa 1870. (Library of Congress) |

As for Edwin Booth, the assassination almost destroyed him. In one foul instant he lost his younger brother, the prestige of his family name and his president. The day after the assassination, Edwin wrote to Adam Badeau and wrung out his feelings on recent events, lamenting the beautiful plans he had had for the future, all blasted now.

In a letter written the same day to Henry C. Jarrett, manager of the Boston Theater, Booth called that April 15 the most distressing day of his life and added, The news of the morning has made me wretched indeed, not only because I have received the unhappy tidings of the suspicions of a brother’s crime, but because a good man and a most justly honored and patriotic ruler has fallen in an hour of national joy by the hand of an assassin.

According to Booth’s friend William Bispham, the events of that 1865 Good Friday brought Edwin Booth stricken to the ground, and it was only the love of his friends that saved him from madness. Bispham and another Booth friend, Thomas Aldritch, took turns staying close to the brooding actor, afraid that if he did not go insane he might resume drinking liquor, which he had given up in 1863.

There were only two things that gave Edwin Booth comfort and helped him persevere through that terrible time: writing his autobiography, which he began in the form of letters to his daughter Edwina, and, as he told Bispham, the knowledge that he had saved the slain president’s son from severe injury or death on that train station platform.

While Edwin eventually recovered from the shock of the assassination, the Booth name was to some extent indelibly tainted by the youngest brother’s deed. Bispham related that one New York newspaper predicted none of the Booth clan would ever be permitted to perform on any American stage again. For a time Edwin feared to leave his house during the daytime. The assassination, as well as the universal vilification of his family, led Edwin to retire from acting for nearly a year.

The story of Robert’s rescue by Booth seemed such an ironic coincidence that a number of people who heard the tale decided to record it for posterity — with varying degrees of factuality. While Booth himself never actually wrote about the incident, Robert Lincoln penned at least three separate narratives of the episode and spoke of it at least twice.

|

| Robert Todd Lincoln at dedication ceremonies for the Lincoln Memorial in Washington in 1922. (Library of Congress) |

Lincoln first told the story to Badeau when they were both serving on Grant’s staff. Badeau subsequently corresponded with Booth about the incident. Two 19th-century accounts of the rescue were written in 1893, the year of Booth’s death.

An article in the Boston Morning Journal, reporting on Booth’s funeral, contains the first known printed narrative of the rescue: At Bowling Green, Ky., it happened that Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Booth were waiting for a train. Neither was aware of the other’s presence. Mr. Lincoln had strayed on a switching track. An engine came along, and he would have undoubtedly been struck and probably killed had not Mr. Booth, with a quick movement, pushed him out of harm’s way.

The article, which does not reveal its source, is grossly inaccurate. It would, however, serve not only as the first recorded narrative of the event but also as the basis for a much later narrative, written in 1919, that would be even more fictitious and absurd.

The second 1893 narrative was Bispham’s, in the November issue of The Century Magazine. While the general events—when checked against Lincoln’s narrative—are correct, there are some minor inaccuracies that can easily be explained as mistaken recollections 30 years after the event.

Between 1865 and 1908, only the two narratives of the incident were published, both focusing on Booth. Between 1909 and 1979 there were 11 narratives of the incident published, all of them centered on the fact that the man saved was the son of Abraham Lincoln. This increased interest and shift of focus occurred because Lincoln’s place in American memory changed.

From 1875 to 1908, Lincoln stood second to George Washington in terms of presidential greatness. But a turning point in Lincoln’s historical reputation came during the centennial year of his birth, 1909. The centennial rites, coupled with the fading numbers of the Civil War generation, many of whom had hated Lincoln and his vigorous nationalism, boosted Lincoln to the top of the presidential list. The resulting glorification of Lincoln was reflected in the voluminous writings about him, his family, his friends and his enemies.

In 1909 the quintessential narrative of Booth’s rescue of Robert Lincoln was published in The Century Magazine. The article, titled Edwin Booth and Lincoln, focused on Edwin Booth’s reaction to the news of the assassination and quoted his letter to Badeau in which he lamented his blasted plans. The story included a synopsis of Bispham’s 1893 reminiscence and also included excerpts of Robert Lincoln’s letter to Richard Watson Gilder explaining the incident.

In 1917 Abraham Lincoln biographer Isaac Markens, with whom Robert had a continuing correspondence, asked Robert to verify the Booth incident. Unfortunately, there is no indication of where Markens heard or read about the story. Lincoln responded that it was true and said the letter recounting it as published in the The Century Magazine in 1909 was exactly correct, for I remember writing it.

The following year, Commodore E.C. Benedict, a friend and traveling companion of Booth’s, corresponded with Robert Lincoln and asked for verification of the rescue story as told to him by Booth. Benedict wrote about the incident in Valentine’s Manual of Old New York in 1922.

Lincoln’s response to Benedict’s letter, dated February 17, 1918, is the most comprehensive narrative of the incident that the reticent Lincoln ever wrote. The description of the actual incident is very similar to the Gilder letter, but here the president’s son clarified the level of actual danger he had faced when he fell. After Booth pulled him to his feet on the platform, Lincoln wrote, The motion of the train had stopped, for it was only a movement of a few feet and not for a start on its journey. This makes it clear that Robert was neither facing an oncoming train nor about to be crushed by a moving locomotive. Instead, he was in momentary jeopardy while the stationary train moved a few feet. This is not the danger of horrible and imminent death that the legends surrounding the story have come to convey. Robert wrote to Benedict that he was probably saved by [Booth] from a very bad injury if not something more.

One year after Benedict’s correspondence with Lincoln, in 1919 the Harrodsburg (Ky.) Democrat printed an article that purported to recite the rescue story. The reporter quoted the story firsthand from a member of a group of gossips, who maintained that he was on the platform in Bowling Green, Ky., when the incident occurred. The gossip said he saw a distinguished looking and heavy-set man pacing back and forth on the track as if in deep meditation. The train then approached, unnoticed by the man, and that’s when Booth jumped from the platform and jerked him by the collar off the track. The two men rolled down the slight embankment and landed in a mud puddle. The great actor was none too soon, for a moment after they rolled from the track the wheels passed over the spot where the unconscious stranger had stood. The gossip wondered if Robert T. Lincoln, the secretary of war, was ever aware that it was Edwin Booth who saved him.

This version of the tale is so flagrantly fictional that anyone who knows the true story can’t help but laugh — anyone except perhaps Robert Lincoln. When his aunt, Emilie Todd Helm, with whom Robert corresponded nearly his entire adult life, saw the article, she mailed it to him and asked if it were true. Robert responded: The headline states a fact.

Every clause in the article is an untruthful invention….The teller of the story as an eyewitness is simply a liar, who had in some way heard of an event which justified the headline and wished to make himself interesting on some occasion.Two days after Robert’s death in 1926, an Albany, N.Y., newspaper published the final account Robert Lincoln gave of his rescue by Booth. The story quotes the head of the manuscript department at the Library of Congress, Charles A. Moore, who disclosed yesterday the Robert Lincoln-Edwin Booth incident based on the first-hand information given him by Robert Todd Lincoln during their many conferences on the library’s acquiring Abraham Lincoln’s papers from Robert.

Over the next 20 years, three Booth biographers — Richard Lockridge, Stanley Kimmel and Eleanor Ruggles — mentioned the rescue, all adding their individual exaggerations, mostly hyperbole about Booth’s derring-do as rescuer. The Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society debuted its Lincolniana section in 1948 with a brief description of the Robert Lincoln-Edwin Booth incident, while the lone book-length biography of Robert Todd Lincoln, originally published in 1969, briefly mentions the incident and quotes Lincoln’s 1909 description of it.

In 1957 a popular periodical titled Coronet repeated the story as action-adventure, full of suspense and drama, but failed to mention it was based on fact. That story begins with Edwin Booth living in seclusion, shocked and sickened by the assassination with his only consolation in this, his darkest hour…a letter he clutched in his hand. The story then describes the rescue fairly accurately, but with little dashes of drama. In this account, Booth rushed onto the platform to catch the train. The train started with a jolt. Edwin Booth, momentarily thrown off balance…recovered himself to see with horror that a well-dressed young man had lost his footing and fallen between the station platform and the moving train. Holding to a handrail, Booth reached down, grabbed him by the collar and pulled him back to safety.

The letter of consolation clutched in Booth’s hand is revealed in the end to be the one written by Badeau, informing Booth of the identity of the man he had saved. Booth forgot about the letter and the incident until the night of the assassination. For, while a Booth had taken a Lincoln life, it revealed that another Booth had saved one. The young man had been Robert Todd Lincoln — the President’s son.

The final published narrative of the incident, in a 1979 issue of American History Illustrated, is an amalgamation of previous narratives, with nothing new added.

The assassination of Abraham Lincoln by John Wilkes Booth only briefly halted Edwin Booth’s acting career. He retired from the stage for eight months, returning on January 3, 1866, in the role of Hamlet at the Winter Garden Theatre. Reviews of his return performance were unanimous, not only in their praise of his acting but also in the descriptions of the audience’s ecstatic reaction. The New York Times said that when Booth appeared on stage during Act 1, Scene 2, the applause extended from the parquet to the dome. There was not a solitary dissentient voice to the manly welcome which every decent person knew ought to be extended to him. The New York World concurred, reporting that when Booth appeared on stage, The men stamped, clapped their hands, and hurrahed continuously; the ladies rose in their seats and waved a thousand handkerchiefs; and for a full five minutes a scene of wild excitement forbade the progress of the play.

Ironically, two weeks before that triumphant return to the public eye, Booth had written to his friend Emma Carey that public sympathy notwithstanding, he would have renounced acting altogether were it not for his huge debts and my sudden resolve to abandon the heavy, aching gloom of my little red room, where I have sat so long chewing my heart in solitude.

In 1868-69 Booth built his own theater — Booth’s Theater — at the corner of 23rd Street and Fifth Avenue in New York and organized a company that produced Shakespearean plays with great success for a time. After going bankrupt and losing his theater in 1874, he rebounded and helped form the Players’ Club, a gathering place for actors and other eminent men at his residence in Grammercy Park, N.Y., in 1888. He died in 1893.

Robert Todd Lincoln, while generally regarded as having lived forever in his father’s shadow, achieved much in his own right. He served as secretary of war under President James A. Garfield, minister to England under President Benjamin Harrison and president of the Pullman Car Company. Republican Party leaders often mentioned the martyred president’s son as a potential presidential candidate.

Lincoln and Booth never corresponded about the incident at the train station, yet neither ever forgot it. Booth frequently mentioned the event to friends, some of whom — as we have seen — wrote about it. Lincoln himself wrote and spoke about the incident numerous times, including his 1918 letter to Benedict, in which he wrote, I never again met Mr. Booth personally, but I have always had most grateful recollection of his prompt action on my behalf.

This article was written by Jason Emerson and originally published in the April 2005 issue of Civil War Times. Jason Emerson is a former National Park Service park ranger/historical interpreter who has published articles in a variety of periodicals.