It’s Christmas Eve 1958 at 4 p.m. I am visiting home outside Boston after working in New Mexico for several months following college graduation in May. The phone rings and I’m the only one in the house, so I answer and the caller asks for me. He says he is calling from Navy Air recruiting and they have a class date for me to begin pilot training in Pensacola, Fla., on January 10. Am I interested?

Yes, I am interested! Exhilarated, elated, euphoric, overjoyed because I have dreamed of flying as long as I can remember. And because I’m not necessarily a strong candidate—English major, lousy GPA, no athletic track record. But they have a class to fill, so I guess the first one to answer the phone gets the slot. Merry Christmas!

I drive into Boston and propose to my girlfriend Fran. We marry seven days later and on January 10 I report to the preflight school at Naval Air Station Pensacola. (Fran and I celebrated our 62nd anniversary this year.)

Preflight is four months of academics, physical training, swimming and military indoctrination. Our class has 22 guys from all over the country and we settle in for the training. Our first test is PT and I fail. I go back the next evening and pass, barely, but that obviates the need for any extra PT, which would reduce the time for studying. And I’m going to need that time.

We are given a course curriculum with books and a slide rule. Really? Do they expect English majors to know how to use a slide rule? The answer is a definite yes. Use every scale on the slide rule or fail the math course and be eliminated. I move into a room with C.J. and George, both engineering majors, and spend weeks mastering that tool with their help.

Then there is swimming, which is another of my weak points. In eight weeks of half days in the pool we will swim above and below and around, including a mile swim with our clothes on, and experience the “Dilbert Dunker” survival trainer. PT includes all the normal activities plus parachute training and trampoline and an obstacle course. Academics focus on navigation, aerodynamics, engines and weather, which the Navy then calls aerology.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

The four-month preflight school concludes with three days in the Eglin swamps on a survival training exercise. We survive three days of pouring rain and eat a black snake. Memorable!

After a whirlwind four months we graduate as “nuggets”—newly commissioned ensigns—and are free to live off base. Following the ceremony, we are expected to give a silver dollar to the first enlisted guy who salutes us, and amazingly there is a chief petty officer standing at the exit to collect his booty. He has done this before.

Next stop is Saufley Field, about 10 miles away, where we will start flying the Beechcraft T-34 Mentor. My first day at Saufley I follow a flatbed truck carrying a crumpled T-34 back from an accident site where two had died. Sobering!

My instructor is a likeable guy named Ron Baker who is a “plowback,” meaning that following his graduation from flight training he was immediately sent back as an instructor. After 12 flights I am cleared to fly solo and continue with Baker as he trains me through an aerobatic curriculum for another 30 hours. We do multiple upsets and spins. Straight up and straight down, inverted flight, loops, Immelmanns, chandelles and countless landings. It is wonderful basic airmanship training that will stick with me for my entire career. Amazingly, I seem to do OK while nearly half my preflight class washes out. Studying poetry is apparently an advantage.

After two months and 43 hours in that little bird the next stop is North Whiting Field northeast of Pensacola, where we transition to the North American T-28 Trojan, a rugged beast with 1,500 hp and the performance of an early World War II fighter. The T-28 is actually a very nice airplane but I flunk my pre-solo check after enduring six hours with a screamer. No serious instruction, just verbal eruptions over any mistake.

Getting a check ride “down” is serious because a repeat would mean elimination and transfer to navigator training with no chance of ever returning to pilot training. My new instructor, Lieutenant Martin, is a natural teacher. One of my brain locks is to forget to move the mixture control to “rich” for climbs and descents, but Martin has an ingenious solution. During a cookout at his home he takes my wife Fran aside and instructs her to whisper “mixture rich” in my ear every night as we lie in bed, which she does. I pass my next pre-solo check and we move on. Now more than 60 years later I still occasionally hear that whisper, “mixture rich.”

At North Whiting the curriculum is precision and aerobatics—loops, Immelmanns, barrel rolls, Cuban eights and spins. The Navy loves spins, left and right, over and over. And every conceivable form of upset, including torque rolls. The T-28 has enough torque that a sudden application of takeoff power when in the landing configuration at approach speed will roll the airplane inverted with no control movement. All of it is truly great training in basic airmanship. This phase takes another two months and 42 flying hours and we then move to South Whiting Field.

South Whiting training begins with a short course in basic instruments and the rest is formation and gunnery. The formation curriculum is challenging and the attrition rate is high. We begin with two-plane formation, break-ups and rendezvous, learning to follow and to lead. It is great fun but there is little forgiveness in this phase. Several friends wash out at this point and I have a close call.

On my fourth formation flight, immediately preceding the solo check ride, my instructor tells me that although the flight was OK he is going to do me a favor. He is giving me a down so that I will get two extra instructional rides before the check ride. A favor? Are you serious? With that down on my record one small error on the check ride and I am eliminated. I am so angry I can barely contain myself, but inflicting bodily harm on a fellow officer will only make this worse, much worse. And especially since on the very first “extra time” flight the new instructor says, “This is a shame, because it would have been a good check ride.”

The actual check ride is with a little Marine major I have never seen before. My wingman for this check takes off before me and is supposed to begin a shallow right turn—15 degrees of bank or less—to accommodate my join-up but he immediately rolls into a 30-degree bank, which greatly complicates any attempt to catch him and join up. My angry response is to break ground and immediately turn so steeply that I have to watch the wingtip clearance with the runway as I initiate the turn and raise the gear. I am at 40 degrees of bank, 20 feet off the ground but I am determined to catch my lead. It is a risky maneuver because it is overly aggressive and I don’t know how that major in the back seat will respond. But I catch the lead, join up and the flight goes well. When we return I am apprehensive about how this will go down but the major is all Marine and loves the aggression. Semper Fi!

We move on to four-plane formation and cross-country flights and then a short course in aerial gunnery. We fly out over the Gulf and shoot at a sleeve towed by another T-28. Wonderful fun.

Next we will be assigned to a “pipeline”—specific training for fighters, multiengine, blimps (yes, still part of the Navy) or helicopters. When I meet with the detail officer he first makes it clear that he doesn’t care about my preference but then says the only pipelines currently open are multiengine or helicopters. Since I have heard that nuggets sent to ME squadrons spend a year or two on the navigator table, I ask for helicopters. Helicopters are relatively new everywhere in 1959 and maybe that will mean a good job market when I am discharged.

I am assigned to helicopter training at Ellyson Field, which is within commuting distance, a good deal for me because Fran is pregnant and that will save at least one move. But in the Navy’s deep wisdom we are sent to multiengine training first in the Beechcraft SNB (C-45), back at North Whiting.

The SNB course is a combination of multiengine and instrument training. It is a great curriculum because I can check off the multi box when I apply for a civilian license, and it is serious instrument training, although somewhat dated. The Navy does not use ILS (instrument landing system) radio navigation, so we do not train for that, but we do train for LFR (low frequency radio range) approaches, which were established in 1928 for airmail pilots. It is primitive but reasonably effective. We also train in MDF (manual direction finder) approaches, another anachronism that amounted to an ADF (automatic direction finder) but without the automation, so the signal antenna had to be tuned manually. These are challenging and archaic technologies but they’re excellent for developing our fundamental instrument flying skills while drilling the humid, turbulent spring skies of Florida.

Cross-country training takes us to Minot, N.D., because that’s where the instructor’s family lives. En route we stop at NAS Olathe, Kan., but make a short hop into Kansas City for the evening. The instructor drinks too much so fellow trainee Vito Cutrone and I fly the airplane back to Olathe while Lieutenant Instructor is unconscious in the back and we have a “get out of jail free” card for any infractions on this trip.

I leave North Whiting with 203 hours of total time. After that it is on to helicopter training at Ellyson Field.

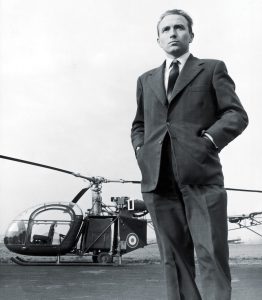

We start with ground training on helicopter weirdness, which is vast—the weirdness, that is. Our initial rotary trainer is the Bell HTL-6 Sioux, that bubble-canopy helicopter you can see on any episode of “M*A*S*H.” Training begins in the middle of a 10-acre grass field when the instructor gives me control and tells me to hover but just stay within the 10 acres. And for the first hour or so that’s about all as I can do. But, like riding a bicycle, it suddenly clicks and we move on to other maneuvers.

Midway through the helo training at morning muster we hear a long list of names called out, followed by the announcement that those named are hereby eliminated from flight training and that the rest of us will be graduated only as needed. The pressure is on.

Advanced helo training is in the much larger Sikorsky HO4S (H-19) Chickasaw and repeats the curriculum from the smaller helo. During this time I meet a fellow student who has just failed his final check ride after 18 months and is eliminated, never to return. More pressure.

My final check ride is a nail-biter because everything depends on it. The check pilot is another little Marine major named Pulaski, a quiet man. I start up, taxi and take off. Major Pulaski says, “Just fly up to the paper mill,” which is about 15 miles north. Then, “Fly around the mill.” Then, “OK, let’s go back.”

Go back? Really? Have I performed so poorly that this is over? What about those multiple required maneuvers for any check ride? Is my aviation career over?

We return to Ellyson, shut down and Major P. says, “Congratulations! Have a nice career.” It’s over, in a good way.

Two days later, on June 30, 1960, Fran pins on my gold Navy wings and I am free to: “Slip the surly bonds of Earth / And dance the skies on laughter-silvered wings; / Put out my hand and touch the face of God.”

Dan Manningham served for five years in the U.S. Navy flying helicopters, followed by a 33-year career with United Airlines. He wrote about his experiences in Helicopter Anti-Submarine Squadron 5 (HS-5) in the March 2020 issue’s “The Night Dippers.”

This feature originally appeared in the May 2021 issue of Aviation History. For more great reading, subscribe today!