Admiral William Leahy was the acting commander in chief as the president’s health failed

“Bill, I’m going to promote you to a higher rank.”

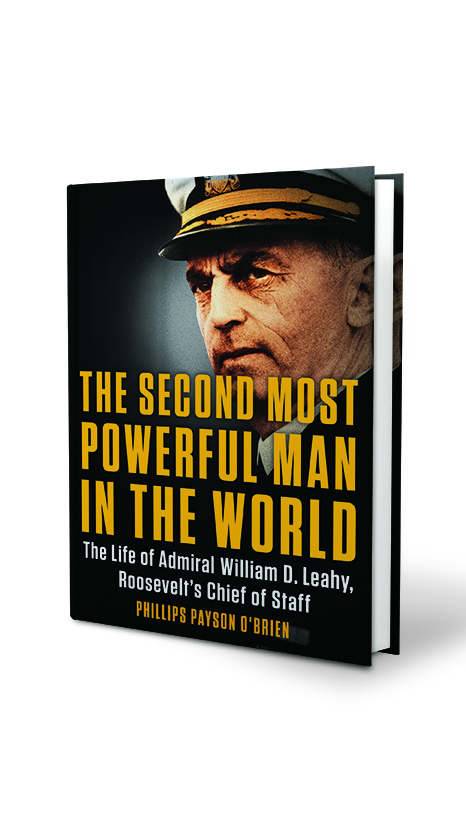

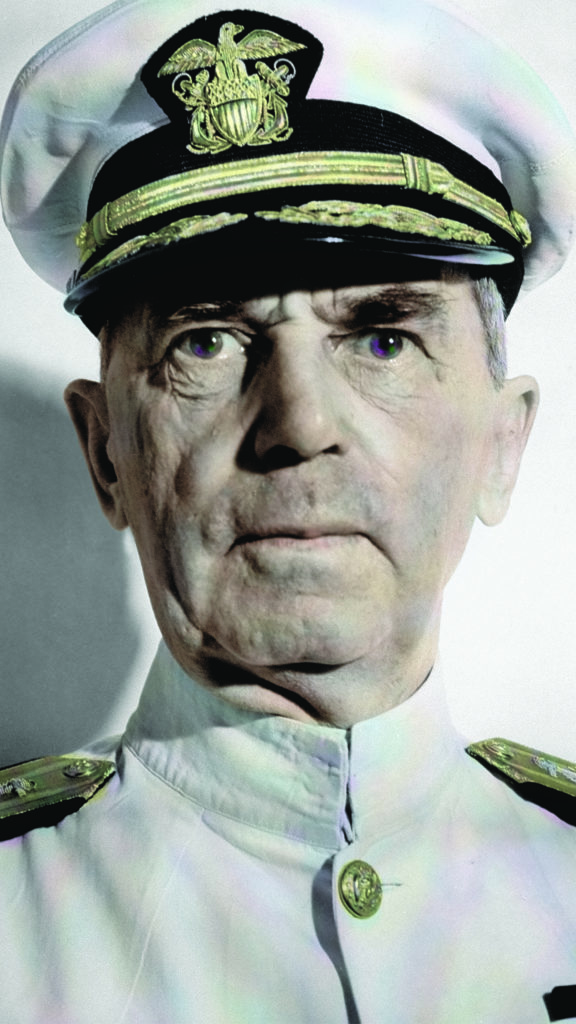

In early January 1944, an increasingly weak President Franklin Roosevelt turned to William Leahy in the White House and told his longtime friend that he wanted to make Leahy, since 1942 the president’s chief of staff, America’s only serving five-star military officer. FDR said nothing about promoting Army Chief of Staff George Marshall, Chief of Naval Operations Ernest King, or General of the Air Force Henry Arnold, but Leahy was adamant that the other Joint Chiefs of Staff be advanced as well, and the president relented. Leahy quickly moved on Roosevelt’s plan, meeting with Representative Carl Vinson (D-Georgia), chairman of the House Naval Affairs Committee and a longtime Leahy friend. The plan entered the congressional pipeline.

Roosevelt and Leahy went back more than 30 years. In 1912, Roosevelt, 30, was a rising Democratic politician and assistant secretary of the Navy. Leahy, 39, was a U.S. Navy captain. His specialty was gunnery, a skill he had brought to bear on a recent American incursion into Nicaragua. His performance there, and his reputation for political savvy, had led to Leahy’s appointment as the Navy’s assistant director of target practice, bringing him into Roosevelt’s orbit. Each enjoyed the other’s company, and the men became friends, fixtures in their respective Washington circles, and powerful figures. In 1937 President Roosevelt named Admiral Leahy U.S. chief of naval operations. The two collaborated to enlarge the Navy for what seemed destined to be a two-ocean war. Upon Leahy’s retirement from the Navy in 1939, Roosevelt named him governor of Puerto Rico, a civilian position with a strong martial component. In 1940, he made Leahy ambassador to Vichy France. In April 1942, an embolism claimed Louise Leahy. That June, accompanying her coffin, William Leahy sailed home. He buried his wife at Arlington National Cemetery. His president had a new job for him: he was to be the first chief of staff to the commander in chief, Army and Navy of the United States, presiding over the Joint Chiefs of Staff and serving as FDR’s most senior military adviser. William Leahy was to have, as the saying goes, a very good war.

Leahy was at the height of his power when he got those five stars. He was FDR’s most important strategic advisor and more than comfortable as chairman of the Joint Chiefs. He had grafted his vision of how the war would be won in both Europe and the Pacific onto the American war effort. The Allies would invade France in the spring, with the Italian campaign resuming secondary status, and, for all the fine words about Germany-first, the war in the Pacific would receive a huge American effort. The war was progressing well, Leahy thought; he hoped the Allies might beat Germany by the end of 1944 and, by the end of 1945, force the Japanese to capitulate. Leahy’s biggest worry was not the war—it was Roosevelt’s health. The president had returned from a December 1943 conference with Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin in Tehran, Iran, in a state of exhaustion. Roosevelt and Leahy continued their daily briefings when the president was well enough, but as Roosevelt slept more the start times were pushed later and later into the morning.

In his 1950 memoir, I Was There, Leahy trod a fine line in discussing Roosevelt’s decline. “The terrific burden of being in effect Commander-in-Chief of the greatest war yet recorded in global history began to tell on Franklin Roosevelt in 1944,” he wrote. “He required more rest and it took him longer to shake off the effect of a simple cold or of the bronchitis to which he was vulnerable.” In truth, Roosevelt was dying. His heart was deteriorating, and his arteries were narrowing; his blood pressure could soar, putting him at constant risk of heart failure or stroke. His appearance could shock those who had not seen him for a while. He steadily lost weight, his cheeks hollowing and his skin taking on a grayish hue. His hands shook, and he often slumped back in his wheelchair, seeming exhausted or disinterested. He barely was able to work. In January he took two weeks completely off, and more than a week each in February and March, spending much of the time at his home in Hyde Park, New York. Americans, however, were being deceived. FDR’s personal physician, Admiral Ross McIntire, stated that Roosevelt, who was only 62, was in fine condition for his age. McIntire later destroyed some of Roosevelt’s medical files to keep the truth from emerging.

Leahy knew the truth, but never said anything. At the time and later, he was torn between writing about what he was seeing in his friend and his desire to protect first the man and then the legacy of Franklin Roosevelt.

Worried constantly about Roosevelt’s health, he was covering for the president, who was skipping whole workdays and -weeks. When these absences came up, Leahy usually described the president’s health issues through outward explanations such as bronchitis or influenza, never admitting the underlying concerns, such as hypertension or heart failure.

To make matters worse, Harry Hopkins’s health was even worse. On New Year’s Day, Hopkins, Roosevelt’s longtime political counselor, collapsed. His health had been precarious for years, and recently he had undergone cancer surgery to remove 75 percent of his stomach. Three days later he checked himself into the hospital for emergency care. His weight had dropped to 126 lbs., and the malnutrition brought on by his compromised digestive system had left him perilously weak. Hopkins began months of shuttling in and out of treatment, including more surgeries, often at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. His physical separation from Roosevelt accentuated an emotional distance growing between him and the president.

These developments meant that in the period between January 1944 and Roosevelt’s death in April 1945 Leahy was controlling much of American strategic and foreign policy. FDR, understanding the extent to which he had grown to rely on the admiral, began involving Leahy even more in his political and private life. Leahy became more forward with his own policy preferences—a noticeable shift, as if he was aware that his influence was growing.

Leahy, who always was protective of Roosevelt, started acting even more ruthlessly as a gatekeeper. A range of people, from the other Joint Chiefs to industrialists to representatives of Allied nations and even major American political figures, had to go through Leahy to get issues brought to the president’s attention. Leahy often became the voice of the president. He drafted many, maybe even most, of the telegrams transmitted that year to Winston Churchill and to Josef Stalin, one of the reasons that Roosevelt’s messages during this period were particularly dull.

In Roosevelt’s stead, Leahy also became the court of appeals on even the most sensitive policy questions. On January 22, when Roosevelt was in Hyde Park, Assistant Secretary of War John McCloy came to Leahy to get approval, following D-Day, for General Dwight Eisenhower to turn over to the Gaullist French Committee of National Liberation civil administration of areas of liberated France. Leahy replied that if it was all right with the State Department, it was all right with him. On February 4, determined to see the British live up to their end of agreements, he drafted and sent to Churchill a formal telegram urging the British to turn over some captured Italian naval assets to the Soviets. On February 23, with Roosevelt again resting at Hyde Park, Leahy worked with the new undersecretary of state, Edward Stettinius Jr., to clarify U.S. policy toward oil-producing regions of the Middle East. Leahy spent much of March on economic issues, such as efforts by Electric Boat Company, the largest American submarine manufacturer, to protect the draft deferments of 300 of its specialists in Groton, Connecticut. Also in March, with Roosevelt just back from yet another Hyde Park stay, Leahy lunched with Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau to discuss when the U.S. should offer its allies a new wartime loan—the beginning of regular lunchtime meetings between the men.

Roosevelt’s health did not improve. In late March, Leahy admitted that even after a week of total rest the president’s “bronchitis” was persisting. FDR needed a long break, somewhere warm and completely isolated.

On April 8, the president’s train again pulled out of Washington late at night, this time heading south for Hobcaw Barony, an estate in coastal South Carolina owned by financier Bernard Baruch. There is something touching, if melancholy, about Leahy and Roosevelt during this holiday. For a month, Leahy had to be both the president’s close friend and his sole link to serious war work. Hobcaw’s 20,000 acres of pine forest, streams, and swamps was a perfect place for a “recuperative vacation” during which Roosevelt planned to sleep 12 hours a day. Except for the incessant insects, which particularly seemed to irritate Leahy, the estate was an oasis of quiet and privacy. Baruch’s daughter Belle, who resided on a neighboring property, was a tall lesbian who lived openly with a number of lovers—or, as Leahy quaintly termed them, “women friends.” He found Belle educated and entertaining and marveled in his diary that on one afternoon hunt she had been the only one to shoot an alligator. A bond of friendship formed, and Belle would even visit the admiral when she passed through Washington.

At Hobcaw Leahy did everything possible to protect Roosevelt. To those in the know, he was practically running the war. White House naval aide William Rigdon, who tracked all the in- and outgoing information from the White House Map Room, noted how Leahy was in control:

“My Hobcaw log, and all other logs, show that Admiral Leahy was always close to the President. He was not only the President’s chief

planning officer, head of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the highest-ranking American officer on military duty—he held ‘five-star’ commission number one—but he was also the President’s confidant and adviser on matters other than the military. FDR trusted him completely.”

The routine at Hobcaw showed how weak Roosevelt had become and how much he had grown to rely on Leahy. After an early breakfast, Leahy would review all top-secret dispatches sent to the president. He would answer some on his own, disregard others, and decide which needed to be discussed personally with Roosevelt. The president rose late and was unable to work until noon, at which point he and Leahy went through the messages Leahy had selected. For about an hour they would make decisions and plan responses before Roosevelt’s workday was done and lunch was served.

The president rested again until about four o’clock when his party—including presidential appointments secretary Edwin “Pa” Watson and other intimates—usually went for an excursion. Car rides and alligator hunts were options, but mostly the choice was a fishing trip along a snakelike system of creeks and inlets that carved up marshland or led into the Atlantic. The fishing was terrible, mostly slow trolling as the president let his line dangle limply in the water. Leahy usually sat next to Roosevelt, at the president’s insistence. Back on land, they would enjoy an early dinner, sometimes with jokes at Pa Watson’s expense, followed by a movie or a game of cards. Roosevelt typically retired to bed not long after dinner.

Slowly Roosevelt’s health began to improve, albeit marginally. More than a week after they arrived, Leahy wrote to his aide in Washington that he still had no idea when the party would return to the capital. On April 28, Navy Secretary Frank Knox died suddenly of a heart attack. The president, keeping Leahy beside him, sent Watson to attend the funeral in his place.

Official visitors were kept to an absolute minimum; Roosevelt wanted only trusted friends around. Perhaps Roosevelt’s favorite visitor was the woman who had once nearly ended his marriage. Lucy Mercer had been serving as Eleanor Roosevelt’s social secretary in 1916 when she embarked on an affair with her boss’s husband. When Eleanor discovered the relationship in 1918, Franklin almost left her, but was forcefully persuaded by his mother to stay married and avoid scandal. He continued to have contact with Lucy Mercer Rutherfurd for decades, and during World War II began to spend time with her when he and Eleanor were apart. During his stay at Hobcaw, Eleanor was allowed to visit only once.

When it came to Lucy Rutherfurd, Leahy was at his most discreet. During the Hobcaw stay, she lodged in a nearby house and visited Roosevelt frequently. Elliott Roosevelt, the president’s son, claimed she came by almost daily. Given Leahy’s near-constant presence with the president, he would have regularly dined and chatted with Rutherfurd, yet he never mentioned it in his diary or to interviewers.

Another favored visitor was Margaret Suckley, an old confidante and distant cousin of Roosevelt’s. She arrived in May and found him still “thin & drawn & not a bit well.” “Everyone conspires to keep the atmosphere light,” she wrote. Suckley found that Roosevelt, having sensed that his doctors were not being honest with him, was now better informed about the seriousness of his medical condition.” Roosevelt must have been aware at times that his health was failing. At other times, he undoubtedly tried to forget this reality and press on.

Leahy, long comfortable with Suckley, confided in her that, to protect the president’s health, he had been rigorously controlling the information shown to FDR and described his dilemma, inadvertently admitting to the immense power he was wielding. Every morning, he confessed, he had to sort through a pile of the president’s confidential correspondence, “analyze it, pass judgment,” and make a recommendation to the Pres. [sic] Half the time it is almost a question of ‘tossing a coin’ to decide one way or the other.”

On May 6 the president finally returned to the White House, his health only marginally better. Leahy wrote optimistically to an aide that “the Boss is in good shape at the end of his vacation.” Admiral McIntire reported to Leahy that the president had returned to his “normal condition” of health. Yet McIntire understood just how weak Roosevelt was; “normal” was hardly a ringing endorsement.

On his first two days back in Washington, Leahy chaired a meeting of the Joint Chiefs, met with newspaper columnist Constantine Brown for the latest Washington gossip, and conferred or dined with a wide variety of influential men, including diplomats Stettinius and Averell Harriman, Navy Undersecretary James Forrestal, War Department Undersecretary Robert Patterson, and Admiral Ernest King. He also hosted the naval representatives of the Dutch and Free French governments.

Spring 1944 marked the start of one of the most intensely political periods in Leahy’s life. With a wartime election fast approaching, he had constant opportunities to dabble in the political and public side of Roosevelt’s existence. Within days of returning, the president confided, “Bill, I just hate to run again for election. Perhaps the war will by that time have progressed to a point that it will make it unnecessary for me to be a candidate.” Yet when Roosevelt announced a few weeks later that he was running, Leahy was not surprised.

The day after Roosevelt’s announcement, Harry Hopkins, just back to work after another long break at the Mayo Clinic, stopped by Leahy’s office to discuss politics—specifically, the vice presidency. Vice President Henry Wallace was at the far left of the Democratic Party, and no favorite of Leahy’s. Hopkins felt he could use Leahy to influence the president and push Jimmy Byrnes, a Roosevelt ally who had represented South Carolina in the U.S. Senate and served on the U.S. Supreme Court, a sinecure he had given up at FDR’s request to head the Office of War Mobilization, for the second spot. Leahy also thought Byrnes the best person to be vice president. Leahy had worked closely with Byrnes on war production and manpower policy, and subtly had been lobbying Roosevelt to put him on the ticket in 1944. But the more closely Roosevelt worked with Byrnes the more he soured on the South Carolinian, recognizing in him a streak of extreme self-importance.

That Harry Hopkins now needed Leahy’s support on issues like Roosevelt’s VP had,

perhaps strangely, led to Hopkins’s relationship with Leahy arriving at its most trusting point. When Hopkins was well enough to work, he and Leahy together drafted important telegrams, particularly on politically sensitive topics. At other times they collaborated to control the Joint Chiefs. One, when Hopkins felt Ernest King, a committed Anglophobe, had given a deliberately antagonistic order to the American naval

commander in the Mediterranean to forbid the use of American equipment to a British-led operation, he hurried to Leahy to get the order countermanded. Leahy agreed with Hopkins and advised the chief of naval operations that it would be sensible if he backed down—which King dutifully did.

Even vital questions such as aid to the Soviet Union, which were extremely important to Hopkins and which he had tried to dominate earlier in the war, now often were referred to Leahy in the hope that the admiral would obtain the preferred decision from the president.

Some of the most powerful people in the United States wanted to take advantage of Leahy’s influence with Roosevelt.

Not long after Roosevelt and Leahy left Hobcaw, their host, Bernard Baruch, hoping for a position in government, wrote to the admiral, “You are just tops. You are a good sailor, a fine statesman, and a splendid friend.”

Leahy kept a copy of the letter in his diary, but he was one of the least self-interested people among the powerful names of American history. He never used his post for financial gain and had little in the way of possessions or property. He was scrupulous about not using his influence to benefit himself or his family.

In early 1944, one of his brothers asked if Leahy could prevent the transfer of his son, a Navy man based in Chicago, Illinois, but recently ordered to Newport, Rhode Island—and presumably from there into action.

Leahy refused. In the only example that can be found of Leahy asking a favor for a relative, he wrote in late 1944 to David Sarnoff, boss of RCA and NBC, with a “personal request” that Sarnoff employ his niece in NBC’s new television division. Sarnoff immediately sent back a handwritten note saying he would be delighted to help in any way that he could.

Leahy’s increased authority after Hobcaw also shows in his direct dealing with cabinet members. One of the first things that Leahy asked Roosevelt to do after they returned from the South was to appoint James Forrestal secretary of the Navy. Leahy had excellent relations with Forrestal and believed that they could work closely together. Roosevelt quickly made the appointment.

Leahy began lunching with Morgenthau even more regularly; he used the Treasury secretary to keep tabs on issues that mattered to him. One was lend-lease, announced by FDR in 1940 as a way to aid Britain after the fall of France and to provide both Britain and the Soviet Union with massive economic and military support. Leahy, by nature inclined to isolationism, wanted lend-lease to end when the war was over. Learning that Roosevelt was going to appoint Morgenthau chairman of a committee to oversee the future of lend-lease, Leahy scheduled a lunch with the Treasury secretary to get a full update on his plans.

Leahy’s already strong links with the State Department became more intimate, partly for institutional reasons and partly for personal reasons. In late 1943, after Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles’s forced resignation resulting from his scandalous behavior involving solicitation of men for sex, the State Department started addressing formal inquiries for the Joint Chiefs of Staff directly to Leahy, who scrutinized and signed the responses to those queries. In 1944, H. Freeman Matthews, who had worked for Leahy when he was ambassador to Vichy, became State’s deputy director for the Office of European Affairs, working with the admiral to improve the flow of crucial documents between the military and the diplomats. Matthews would call Leahy if he needed special information or to get the Joint Chiefs’ approval for State Department directives. Secretary of State Cordell Hull’s declining health made him an even more peripheral figure in Leahy’s life. In the summer of 1944 Hull was such an outsider that he often was left to communicate with Roosevelt through Leahy, and even then could not be sure of getting an answer. By November, Hull was in such poor condition that he had to resign and was replaced by Stettinius.

This story appeared in the February 2020 issue of American History.