As his Swordfish biplane, Q for Queenie, clattered noisily through the humid night sky, Royal Navy pilot Charles Lamb peered out from his open cockpit at an incredible scene spread before him. A nightmare of blazing flak, flashing tracer bullets, and explosions illuminated the Italian port of Taranto, home to Benito Mussolini’s battlefleet. Swordfish from the British carriers Indomitable and Eagle weaved just over the water, dodging swaying barrage balloons and slipping through masses of antiaircraft fire so thick and bright that, though camouflaged, the attacking airplanes appeared a “gleaming white.”

The antiaircraft fire also lit the target of the Royal Navy’s attentions: nearly thirty moored warships in Taranto’s inner and outer harbor. The prize was a mix of five battleships and fourteen cruisers, all now firing furiously at the biplanes attempting to lance them with deadly torpedoes. Assigned to drop illuminating flares from a relatively safe height, it occurred to Lamb that although he had never been in less danger himself, his fellow airmen “were flying into the jaws of hell”; he felt certain none could survive. It was November 11, 1940, one of the most memorable and portentous nights in the history of naval aviation.

On June 10, 1940, Mussolini had attacked France, introducing a new and particularly threatening dimension to the Second World War. Britain depended heavily on the Middle East for its trade and oil, and the Royal Navy could not brook any interference with the Empire’s sea lines of communication. It was a staggering challenge: at war’s outbreak Italy’s powerful fleet, the Regia Marina, consisted of more than 250 warships and submarines. With two battleships, the Conte di Cavour and the Giulio Cesare (four other battleships were undergoing modernization or completion), and nineteen cruisers, as well as a robust and well-equipped air force that had, in the interwar years, ranged all across the Mediterranean, the Regia Marina packed a powerful punch. Britain, already heavily engaged in Western Europe, now faced an equally broad war across the Mediterranean, fighting a regional power whose air-minded Duce possessively called the Mediterranean Mare Nostrum—“Our Sea.” The strength of the Italian fleet continued to grow over the summer of 1940, when two new battleships, Littorio and Vittorio Veneto, each armed with nine fifteen-inch cannons, joined the Fascist fleet.

One of Britain’s key assets was a new and powerful aircraft carrier, Illustrious, fitted with a four-inch-thick armored flight deck, and operating one squadron of fighters and two squadrons of torpedo planes. Commissioned in May 1940, the 23,000-ton carrier could attain thirty-one knots, propelled by three turbine-driven screws. Illustrious entered the Mediterranean on August 30, 1940. Time was critical: British forces fighting in the Western Desert were rapidly exhausting available supplies, Malta was endangered, and Prime Minister Winston Churchill and the Admiralty worried incessantly that the Wehrmacht would soon enter the Mediterranean war. Striking a blow against the Italian navy made eminent sense. And striking at its heart made the greatest sense of all.

That heart was the port of Taranto, nestled at the apex of a broad gulf constituting the arched sole of the Italian boot. The port itself was shaped like a lopsided figure eight, with two separate anchorages, an inner and an outer. The inner anchorage, the Mar Piccolo, lay separated from the outer anchorage by a constricted passage permitting transit of smaller vessels; larger warships typically anchored in the outer Mar Grande, framed by the headlands of Cape Rondinella to the northwest and Cape San Vito to the south, with two small harbor islands guarding its mouth. Added to these natural defenses were man-made ones yet unknown to Royal Navy planners—Adm. Arturo Riccardi had ringed the anchorage with barrage balloons to frustrate low-flying airplanes and antitorpedo nets designed to prematurely detonate shallow-running torpedoes.

No surface fleet would survive if it attempted a long-range gun duel against the heavily defended Italian coast. Furthermore, unless protected by its own fighters, it risked a fatal counterattack by Mussolini’s Regia Aeronautica. Thus Taranto demanded a night carrier air attack, something the Royal Navy already did well. Even more remarkably, a Taranto attack plan already existed, drawn up in 1935 as a precautionary response to Mussolini’s aggression against Ethiopia and quietly circulated among Britain’s senior commanders. One of them, Rear Adm. Arthur Lumley St. George Lyster, had served at Taranto during the Great War. He recognized the plan’s brilliance, and used his personal knowledge to refine it further.

Many officers never see the fruits of their labor or enjoy the opportunity to execute something that they have planned. But Lumley Lyster was uniquely positioned to do both. In the fall of 1940 he was a rear admiral, commanding the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean-based aircraft carriers from his flagship, Illustrious. Now he moved to change the plan into reality. In a meeting with Adm. Andrew Browne Cunningham, the Mediterranean fleet commander, Lumley Lyster recommended attacking Taranto, and Cunningham immediately assented.

Key to the success of this plan would be an airplane that looked positively archaic. The Fairey Swordfish biplane, a “TSR” design intended for torpedo, gunfire spotting, and maritime reconnaissance missions, first flew in 1933. It was powered by a 750 hp Bristol Pegasus radial piston engine driving a three-bladed fixed-pitch propeller, and the fabric cover over its large metal structure earned it the affectionate nickname “Stringbag.” The Swordfish carried a three-man crew—pilot, navigator, and gunner—in open cockpits, and either a single 1,610 lb torpedo or 1,500 lb of bombs. With a range of almost 550 miles with a normal fuel load, it had a maximum speed of 138 mph—barely faster than a Great War biplane. Its armament—a single Vickers .303-caliber machine gun firing through the propeller, and another operated by a rear gunner—was actually less than what many World War I warplanes carried. At the outbreak of World War II, Swordfish equipped thirteen Fleet Air Arm squadrons.

To strike at Taranto, a special sixty-gallon long-range fuel tank needed to be installed, taking the place of one of the crew. Fortunately for the British, Illustrious had arrived in the Med with the tanks, and, as mechanics worked to install them, Lumley Lyster set to work training his crews. He aimed for a tentative target date of October 21, Trafalgar Day, and gave the plan the name Operation Judgment.

The training program and operational experience soon produced some valuable and sobering lessons. On the night of October 13–14, Swordfish from Eagle and Illustrious raided the Dodecanese islands, plastering the airfield at Leros with more than one hundred bombs. It was encouraging practice, but the loss of four of Eagle’s Swordfish and their crews in a daytime attack on Rhodes on September 4 demonstrated the aircraft’s great vulnerability to modern fighters and the absolute necessity of using surprise and night. Taranto was known to be the most heavily defended port in the world, and Lumley Lyster’s planners needed precise, up-to-date intelligence on the location of the Italian fleet and the state of Taranto’s defenses.

Fortunately for Lumley Lyster, the Royal Air Force had just the right tool to furnish him with the information he needed: the American-built Martin Model 167F Maryland, a light twin-engine attack bomber. Ordered by France before the war, few had been delivered before Hitler’s Blitzkrieg ended the Third Republic in ignominy and defeat. Providentially, the RAF secured seventy-five of the undelivered aircraft, sending them to the Middle East. Eschewing bombs for cameras and carrying a long-range fuel tank, the 167F had a range of 1,900 miles and an endurance of ten hours; more important, it had a dash speed of nearly 300 mph, sufficient to outrun most intercepting Italian fighters (particularly if it surprised them), and surprising agility, enabling it to evade them if necessary. Simply referred to as “Glenn Martins,” the Marylands of 431 Flight began overflying Taranto out of Luqa on Malta in September, while RAF Sunderlands from Coastal Command’s Malta-based 228 Squadron patrolled the sea lanes, keeping track of Italian ship movements.

Chance now intervened, with further bad news. An Italian air attack had seriously damaged Eagle, contaminating its fuel supply (discovered when several Swordfish crashed) and forcing Lumley Lyster to transfer some of its Swordfish to Illustrious. Then, as mechanics worked to install the long-range tanks, sparks ignited fuel vapors, killing several sailors and briefly endangering all the aircraft in Illustrious’s hangar deck. Fortunately, the carrier’s firefighters and its saltwater quenching system suppressed the blaze and only two aircraft were lost.

It had been a close call; even so, the result impacted the Taranto raid, for five other airplanes had been drenched in salt brine. Because the planes were constructed of aluminum, they had to be cleaned with fresh water, and their engines and radio equipment thoroughly examined to prevent corrosion; these procedures necessitated postponement of Operation Judgment. Trafalgar Day was out; planners decided to slip the attack to November 11 to take advantage of a three-quarter moon. But worse than the delay was the reduction in size of the planned strike package. Together, Illustrious’s fire and Eagle’s fuel contamination problems reduced the attack force by a third, from a maximum of thirty airplanes down to twenty-one.

On November 10 The Sardine Tin, an RAF Martin skippered by twenty-two-year-old Pilot Officer Adrian “Warby”Warburton, returned the penultimate prestrike photos of Taranto. Warburton, the son of a naval officer, had already established a reputation as a daring airman, shooting down an Italian bomber with his Martin on an earlier sortie and surviving encounters with multiple Italian fighters, one of which had resulted in his being briefly knocked unconscious by a spent round. He lived up to his daredevil reputation during the November 10 sortie: low, thick cloud blanketed Malta, forcing Warburton and his crew to fly an extremely low-level mission, right into Taranto harbor itself. Warburton was able to get two full passes around the harbor before its surprised defenders began firing, and he cheekily carried out a third and final pass before exiting for home, hotly pursued by a Fiat fighter. The Martin handily outpaced the biplane Fiat over the next twenty minutes, and the images Warburton brought back revealed that Taranto’s anchorages brimmed with five battleships, fourteen cruisers, and twenty-seven destroyers.

He and his crew had also captured fuzzy images of the harbor’s defenses, including lines of barrage balloons and antitorpedo nets picked off the prints by two keen-eyed photo interpreters, RAF Flight Lt. R. Idris Jones and Fleet Air Arm reservist Lt. David Pollack. Planners took account of the balloon lines, adjusting the attack’s anticipated approach into the harbor accordingly.

The nets were more difficult to confront, but here technology lent a hand. A torpedo net was intended to catch and possibly detonate a torpedo before it reached a ship, under the assumption that a torpedo traveling deep enough to pass under the net would likewise pass too deep to impact a ship. However, Illustrious had a new type of torpedo detonator, a “Duplex” fuze, that would explode the warhead either by direct contact or by magnetic influence. The Duplex fuze enabled the Swordfish to drop deep-running fish that would pass under the nets and then detonate as they passed below the hull of their targets. The compression caused by a torpedo explosion below the hull could cause a ship to break its back. But such an approach also risked the torpedo grounding in shallow water, and it required tremendous skill on the part of the Swordfish crews, who would have to drop their torpedoes from no more than thirty feet lest the missile dive too deep and bury itself in the bottom.

Illustrious, nestled amid a screen of four battleships and numerous cruisers and destroyers, had sortied from Alexandria on November 6, and by midday on November 11 was less than three hundred miles southwest of Taranto. That day the RAF flew two final recce missions over Taranto and found that a sixth battleship had arrived at the harbor: all of Mussolini’s battlewagons now lay at anchor within the Mar Grande, a rare prize. A Swordfish flew out the last prestrike photographs to the fleet planners and final strike preparations got underway.

Though the planners had hoped for surprise, the intensive reconnaissance had tipped the strong level of British interest in Taranto and, further, the activities of offshore patrol planes had not gone unnoticed. Thus when Illustrious launched the first of two attack waves from 170 miles southeast of Taranto at 8:35 p.m., Italian coastal defenses were on high alert.

The first wave of Swordfish, led by Lt. Comdr. Kenneth Williamson, consisted of twelve aircraft: six torpedo planes, four bombers, and two bombers acting as flare dispensers. They climbed through low cloud before breaking out at 7,500 feet in bright moonlight—all except one plane which, unable to locate the formation and fearful of a collision in-cloud, prudently stayed below the cloud deck and made its own way to Taranto, ironically arriving a full fifteen minutes ahead of schedule.

Taranto’s defenders lacked any sort of radar, but they did have multiple diaphonic listening posts, and, though these generally were almost useless, on this night they registered first a Sunderland flying boat offshore, the low-flying and early arriving Swordfish, and, finally, Williamson’s strike package. The noise of their arrival triggered an immediate response. The night erupted in tracers, gun flashes, and wildly swinging searchlights.“There suddenly appeared ahead the most magnificent firework display I had ever seen,” Williamson recalled. “The whole area was full of red and blue bullets. They appeared to approach very slowly until they were just short of the aircraft, then suddenly accelerated and whistled past.”

Here was where crew training, discipline, and the detailed recce photographs proved their worth. As planned, Williamson and two others dived from westward to water level, jinking around to throw off the aim of gunners, threading their way through the balloon barrage. Under intense fire from two destroyers—preraid analysis had predicted that at least 50 percent of all attackers would be shot down at ranges of threequarters of a mile—Williamson released his torpedo, which scored a hit on the battleship Conte di Cavour. Seconds later, its controls shot away, his Swordfish plunged into the water, its crew able to swim to shore and swift captivity. His two wingmen dropped on the Cavour, but missed.

The second flight of the first wave attacked from the northwest, striking through “a hail of red, white, and green balls,” as pilot Lt. M. R. Maund described it, a scene that left him thinking, “This is the end—we cannot get away with the maelstrom around us.” But they did, even managing to score hits with two of their three torpedoes on the battleship Littorio. Over the Mar Piccolo, the four bombers were causing their own havoc, bombing a seaplane base and dock areas. Then the surviving Swordfish made their way out to sea.

Now it was the second wave’s turn. Consisting of nine Swordfish (five torpedo planes, two bombers, and two bomb and flare droppers) led by Lt. Comdr. J. W. Hale, it got off to a bad start when two planes snagged their wings with one another on deck. The second wave, now reduced to seven, launched beginning at 9:23 p.m., though one had to turn back when its long-range fuel tank came adrift, falling into the sea. Briefly it seemed the second wave would be reduced to just six attackers, but one of the two airplanes involved in the collision on deck had been inspected and cleared for flight, and so it took off late on its own. The second wave climbed to eight thousand feet, and saw, far ahead of them, the bright color of antiaircraft fire dotting the sky over Taranto.

It was an amazing sight, at once spectacular and sobering. Again the flare droppers separated to do their illumination, and the five torpedo bombers dived in from the northwest, jinking in their descent to throw off the gunners. They skimmed the water, two picking the Littorio for their torpedoes, a third the battleship Caio Duilio, and a fourth the new Vittorio Veneto. The first two sustained hits, but at a price: Lts. G. W. Bayley and H. J. Slaughter, an Eagle crew detached to Illustrious, disappeared with their Swordfish, shot down over the harbor, and another Swordfish crew experienced an extremely close call, their Stringbag shivering with “a bloody great shudder and bang” as its fixed landing gear hit the sea (fortunately, the pilot retained control and flew safely off).

As earlier, the bombers and flare-droppers caused their own mischief, again keeping much of the antiaircraft fire directed upwards at the moth-like biplanes that flitted annoyingly in and out of the dancing beams. The last of the Swordfish departed Italian airspace shortly after midnight and made their way toward the recovery point, the first landing aboard at 1:20 a.m., and the last following at 1:55. The next morning, Illustrious and its consorts rejoined the main body of the British fleet, welcomed by a special flag signal that Cunningham ordered flown from his flagship: “Illustrious maneuver well executed.”

For a brief while, Cunningham considered a return raid that night, but deteriorating weather, concerns over the alerted defenses, and the tired state of the aircrews led to a sensible decision to withdraw and savor the success that had been achieved. Taranto was history.

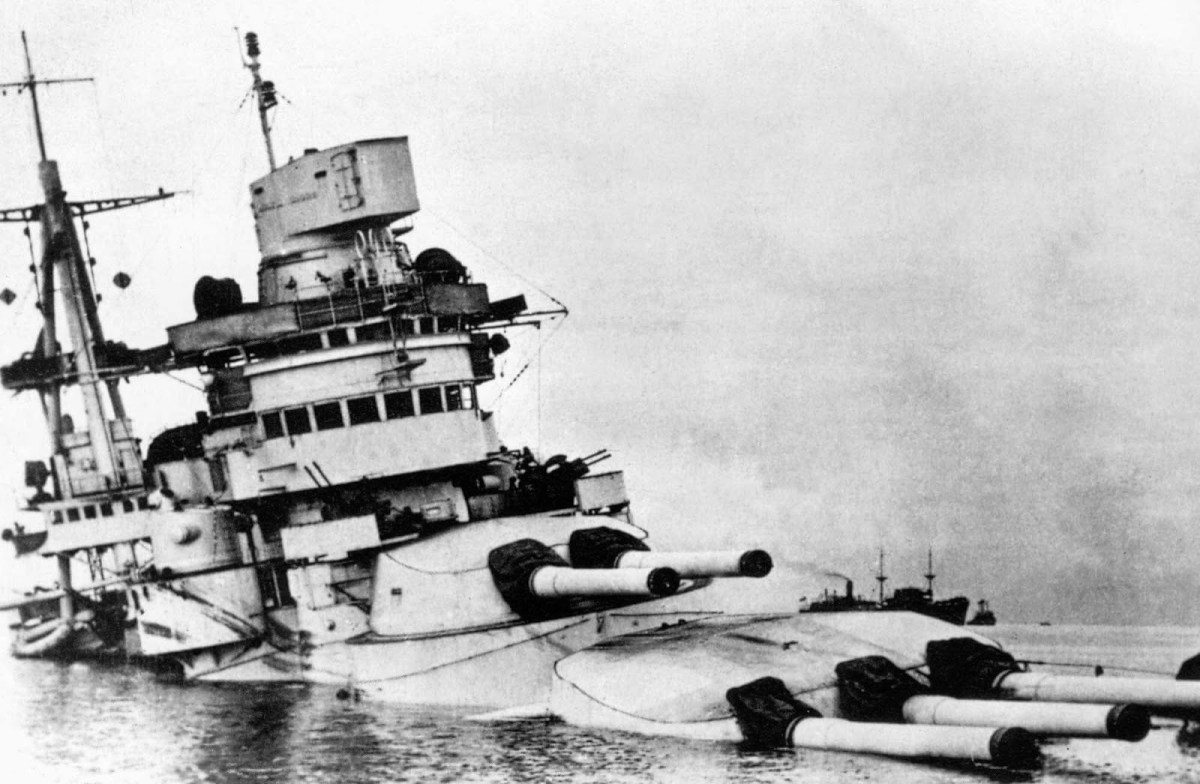

Historians debate the significance of Taranto, but certainly at the time it was perceived as a stunning accomplishment. In the Operations Room of the Supermarina, the Italian naval headquarters, Adm. Marc’Antonio Bragadin took the initial reports of Taranto as the raid unfolded, recalling that the news “grew more and more serious and surprising.…It seemed that a great naval battle had been lost, and no one yet knew if and when it would be possible to recover from the grave consequences of it.” In the morning, Warburton again raced in from Malta, his photographs revealing that three battleships— Littorio, Cavour, and Duilio—had been sunk or beached to prevent sinking, and a cruiser and two destroyers damaged.“More damage,” Cunningham recalled a decade later, “than was inflicted upon the German High Seas Fleet in the daylight action at the Battle of Jutland…the crippling of half the Italian battle-fleet at a blow at Taranto had a profound effect on the naval strategical situation in the Mediterranean.”

Subsequently, the Supermarina issued orders prohibiting mention of the raid. In London, Prime Minister Churchill rose in the House of Commons to praise the “glorious episode,” the “electrified House” responding with “enthusiastic cheers” at “the wonderful Nelsonian news.”

Taranto offered many lessons, not least of which was that the aircraft carrier had succeeded the battleship as the arbiter of naval power. It was something that Brig. Gen. Billy Mitchell, Adm. William Sims, Adm. Jackie Fisher, and others had predicted, but that few maritime traditionalists had believed possible. Even after Taranto, zealots remained unconvinced until the Japanese navy savaged the U.S. Pacific Fleet one December morning at Pearl Harbor, and another bleak day off the Malayan coast when Japanese bombers sank British battleships Prince of Wales and Repulse.

Little about the Taranto raid is more controversial and uncertain than the possible connection between Taranto and Pearl Harbor. In 1936 a young Japanese naval aviator, Minoru Genda, had argued before the Japanese Naval War College that the future of maritime attack belonged to torpedo planes and dive-bombers, statements that caused listeners to question his mental soundness. In 1940, by then a lieutenant commander, he had witnessed firsthand the onset of the Battle of Britain while serving as assistant air attaché at the Japanese Embassy in London. Genda had returned to Japan at its height, convinced Germany would lose. Two months later, Cunningham’s airmen raided Taranto. A zealous advocate of air power in the mold of a naval Billy Mitchell, Genda would formulate his own air assault—the attack on Pearl Harbor—within a year as the principal planner of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s air arm. However, Genda subsequently insisted to naval historian Norman Polmar that Taranto differed so considerably from Pearl Harbor in the manner and style of attack as to be irrelevant to it.

But there can be no doubt that Taranto was discussed by the Japanese, and that if Genda was unmoved by it, others were not so blasé. Just days after Taranto, the assistant air attaché for the Japanese embassy in Berlin, Lt. Comdr. Takeshi Naito, journeyed to the stricken port to study the damage. A larger Japanese military delegation followed in the late spring and early summer of 1941, again visiting the port and asking extensive questions about the raid. In late October 1941, now back in Japan, Naito met with an old friend, Comdr. Mitsuo Fuchida—who would soon lead the Pearl Harbor raid—recalling that Fuchida quizzed him closely on Taranto. For his part, Fuchida recalled years later that “the most difficult problem [at Pearl Harbor] was launching torpedoes in shallow water. The British Navy attacked the Italian fleet at Taranto, and I owe very much for this lesson in shallow-water launching.”

Of the greatest lesson there is no doubt: carrier aviation had at last come of age.

Originally published in the December 2007 issue of World War II Magazine. To subscribe, click here.