Fifty years after the war in Vietnam, Americans are still debating the morality of U.S. involvement there—the reasons the government went in and the way it got out. Political scientist Eric Patterson has compiled a checklist of sorts that provides one way of judging the justness of the war-making strategies pursued by four presidents.

In Just American Wars: Ethical Dilemmas in U.S. Military History, Patterson, a professor at the Robertson School of Government at Regent University and a research fellow at Georgetown University’s Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs, lays out eight principles that serve as the basis for ethical, moral conduct in war. He traces those principles to writings of philosophers such as Cicero in ancient Rome and St. Augustine in the early years of Christianity.

The eight principles of ethical warfare are legitimate authority, just cause, right intent, likelihood of success, proportionality of ends, last resort, proportionality in conduct of the war, and discrimination in conduct of the war.

Patterson, a lieutenant colonel in the Air National Guard, uses those principles to look at ethical dilemmas in various aspects of American wars from the Revolution to the post-9/11 world. In the Vietnam chapter, he focuses on the war aims of U.S. presidents and whether those aims were pursued for legitimate reasons (just cause) and with honorable motivations (right intent).

Reflecting on the French debacle at Dien Bien Phu in 1954, when French forces trying maintain their colonial rule in Vietnam lost a war against a communist-led independence movement, President Dwight D. Eisenhower observed, “You have a row of dominoes set up. You knock over the first one, and what will happen to the last one is the certainty that it will go over very quickly.” Eisenhower had not only Indochina in mind, but the recent war in Korea and “loss” of China to Mao Zedong’s communists in 1949.

Sixteen years later, Eisenhower’s vice president, Richard Nixon, was president and affirmed the “domino theory” at a press conference: “Now I know there are those who say the domino theory is obsolete. They haven’t talked to the dominoes. They should talk to the Thais, to the Malaysians, to the Singaporeans, to the Indonesians, to the Filipinos, to the Japanese, and the rest. And if the United States leaves Vietnam in a way that we are humiliated or defeated… this will be immensely discouraging to the 300 million people from Japan clear around to Thailand in free Asia; and even more important it will be ominously encouraging to the leaders of Communist China and the Soviet Union who are supporting the North Vietnamese.”

In President John F. Kennedy’s 1961 inaugural address, he warned, “Our security may be lost piece by piece, country by country.” President Lyndon B. Johnson put it this way: “If you let a bully come into your front yard one day, the next day he’ll be up on your porch and the day after that he’ll rape your wife in your own bed.”

The domino theory emerged from the experiences of these men, and their advisers, during World War II. There was a shared understanding among their generation that the appeasement at Munich in 1938, which allowed Adolf Hitler to annex part of Czechoslovakia, had emboldened him, and more dominoes began to fall: all of Czechoslovakia and Poland.

The domino theory is really shorthand for a larger set of assumptions that informed U.S. “war aims”—the desired outcomes, stated and unstated, of a political-military strategy—with regard to Vietnam and its neighborhood from the 1950s through the 1970s.

In 1956, Kennedy, then a U.S. senator, claimed that Vietnam was “the cornerstone of the Free World in Southeast Asia, the keystone in the arch, the finger in the dike, and should the red tide of Communism pour into it … much of Asia would be threatened.”

The domino theory demanded active national security and foreign policies from successive presidential administrations. At least five major war aims were used to justify supporting the South Vietnamese government and continuing to fight the Vietnam War:

• Contain communism

• Spread democracy, or at least hold it in places where it already existed

• Demonstrate resolve to various foreign audiences

• Vindicate national honor

• Protect the personal reputation and credibility of the president

The first U.S. war aim was to contain communism. In the early years of the Cold War the United States had to decide on a policy to deal with the apparently insatiable, ubiquitous assault of the Soviet Union and global communism. Some argued that the U.S. should return to its prewar isolationist policy. Even if more European governments fell to Stalin’s Soviet Union, the U.S. was largely safe in North America. Other people, although concerned about the “Red Menace,” felt that it was time for Americans to care for their own. At the other end of the spectrum were those who believed the U.S. should not only stand up to this latest aggressor but consider pushing back if the Soviet Union was going to play hardball.

The U.S. ended up taking a middle road that became known as “containment,” a concept associated with State Department official George Kennan and his “X Article,” published in Foreign Affairs in 1947.

Kennan wrote: “The main element of any United States policy toward the Soviet Union must be that of a long-term, patient but firm and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies … Soviet pressure against the free institutions of the Western world [should be countered] through the adroit and vigilant application of counter-force at a series of constantly shifting geographical and political points, corresponding to the shifts and maneuvers of Soviet policy … [to] promote tendencies which must eventually find their outlet in either the break-up or the gradual mellowing of Soviet power. “

As containment developed as a political-military strategy during Harry S. Truman’s presidency, policies and institutions were established, such as the Truman Doctrine (to support democracies everywhere) and NATO. U.S. leaders saw the defense of a quasi-democratic, Western-oriented South Vietnam (and neutral Laos and Cambodia) as consistent with the containment policy. A NATO sibling was established, the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization, or SEATO.

Eisenhower embraced Truman’s containment policy and its application to Far Eastern “dominoes.” In a 1959 speech, he said, “The loss of South Vietnam would set in motion a crumbling process that could, as it progressed, have grave consequences for us and for freedom.”

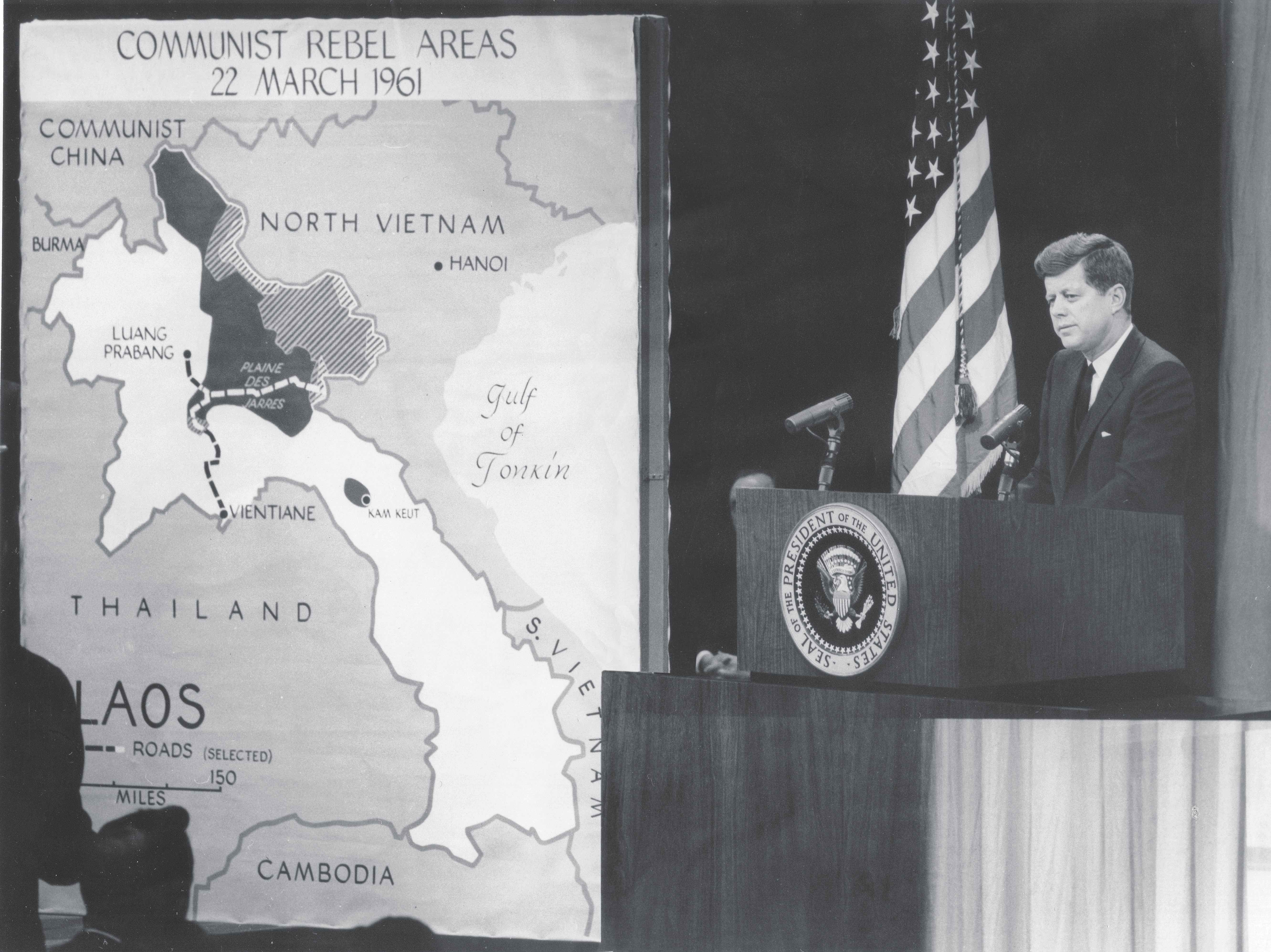

Kennedy had to deal with communist destabilization of Vietnam and Laos from his first days in office. In a March 1961 press conference, he called out communist activity in Laos. A national security memorandum on May 11, 1961, succinctly laid out a policy of containment:

The U.S. objective and concept of operations stated in the report are approved: to prevent Communist domination of South Vietnam; to create in that country a viable and increasingly democratic society, and to initiate, on an accelerated basis, a series of mutually supporting actions of a military, political, economic, psychological and covert character designed to achieve this objective.

Johnson, in an address in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1966, said, “South Vietnam is important to the security of the rest of all of Asia.” He added that the fighting in Vietnam “is buying time not only for South Vietnam, but it is buying time for a new and a vital, growing Asia to emerge and develop additional strength. If South Vietnam were to collapse under Communist pressure from the North, the progress in the rest of Asia would be greatly endangered. And don’t you forget that!”

The second foreign policy principle that became a war aim in Vietnam was the promotion of democracy. In the immediate aftermath of World War II, the Western allies were frustrated by the many promises broken by Soviet leader Josef Stalin, from lingering military detachments in Iran to the lack of free elections in Poland.

In Vietnam, the U.S. goal was to buttress the feeble but existing governing institutions left behind as the French withdrew after the Dien Bien Phu defeat and the 1954 Geneva Conference. The conference agreement temporarily partitioned Vietnam into a communist North and democratic South and provided for an election in 1956 to unify the country.

Washington was keenly aware of just how fragile new democracies, especially in poor countries, could be. The Defense Department estimated that $28.5 billion was spent on democracy and development activities during the most active phase of U.S. involvement in Vietnam. By the end 1956, the trajectories of Saigon and Hanoi were on a collision course. South Vietnam and the U.S. no longer had any immediate expectation of a democratic consensus taking hold over the entire region. They anticipated a divided Vietnam, like Korea, with the South shielded by the U.S. and its allies for years to come.

In Kennedy’s budget message to Congress for fiscal 1964, he wrote: “We are steadfast in our determination to promote the security of the free world, not only through our commitment to join in the defense of freedom, but also through our pledge to contribute to the economic and social development of less privileged, independent peoples.”

In 1965 Johnson, whose focus on empowering the poor was both a domestic and an international policy goal, told an audience at Johns Hopkins University:

The first step is for the countries of Southeast Asia to associate themselves in a greatly expanded cooperative effort for development … I will ask the Congress to join in a billion dollar American investment in this effort… The task is nothing less than to enrich the hopes and existence of more than a hundred million people.

Johnson, like his predecessor, believed that only a modernizing Vietnam could develop rooted democratic institutions and meet the needs of its populace.

Nixon was committed to a policy of “Vietnamization”—developing, as quickly as possible, stable South Vietnamese government and military institutions while ruthlessly forcing the North Vietnamese to the negotiating table by powerful U.S. military intervention. This was an exit strategy with development and democratization elements, rather than a moral commitment to some sort of democratic ideal.

A third U.S. war aim was to demonstrate U.S. resolve. It was a communist maxim that Western governments were weak and effeminate, lacking the staying power to counter the scientific fact of communist progress.

The U.S. government felt that it had to demonstrate to both the communists and America’s allies the credibility of its security guarantees. The U.S. did not want to appear as if it was vacillating in Vietnam because that could signal to countries such as the Philippines or those in Latin America or Europe that the U.S. lacked the will to come to their aid if they were challenged by communism.

Eisenhower reflected in his memoir, “I pointed out that in Korea, Indochina, Formosa, Greece, and elsewhere, the Communists had been stopped in aggressive action only by the interposition of Western resolution and force.”

Kennedy trumpeted in his inaugural address, “Let every nation know, whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty.”

When Kennedy responded two months later to the Laos crisis, he told the world that “no one should doubt our resolution on this point.”

Johnson also emphasized the importance of demonstrating U.S. resolve. In a 1965 speech, he said: “Around the globe, from Berlin to Thailand, are people whose well-being rests, in part, on the belief that they can count on us if they are attacked. To leave Vietnam to its fate would shake the confidence of all these people in the value of American commitment, the value of America’s word. The result would be increased unrest and instability, and even wider war.”

Nixon told the American people in 1973: “For the future of peace, precipitate withdrawal would thus be a disaster of immense magnitude. … Our defeat and humiliation in South Vietnam without question would promote recklessness in the councils of those great powers who have not yet abandoned their goals of world conquest. … Ultimately, this would cost more lives.”

A fourth war aim, one that developed as the war was being fought, was the sanctity of national honor. The moment blood is spilt, war takes on a sacred character.

While running for president, Nixon promised, “I pledge to you that we shall have an honorable end to the war in Vietnam.” And on Jan. 23, 1973, in a televised address on the successful outcome of the Paris peace conference, Nixon repeatedly used the phrase “peace with honor.” He also said, “Let us be proud of the 2½ million young Americans who served in Vietnam, who served with honor and distinction in one of the most selfless enterprises in the history of nations. And let us be proud of those who sacrificed, who gave their lives so that the people of South Vietnam might live in freedom and so that the world might live in peace.”

Kennedy spoke in a very personal way about the sacrifice of the fallen in response to a letter from Mrs. Bobbie Lou Pendergass, whose brother died in a helicopter crash in South Vietnam during January 1963. She asked if her brother’s death had any meaning. The president assured her in a March 1963 letter that “he had not died in vain … earn[ing] the eternal devotion of this Nation and other free men around the world.”

Johnson, in his 1965 Johns Hopkins speech, said:

We are there because we have a promise to keep. Since 1954 every American President has offered support to the people of South Vietnam. We have helped to build, and we have helped to defend. Thus, over many years, we have made a national pledge to help South Vietnam defend its independence. And I intend to keep our promise. To dishonor that pledge, to abandon this small and brave nation to its enemy, and to the terror that must follow, would be an unforgivable wrong.

Similarly, Nixon said in his 1973 speech on the Paris agreement, “A nation cannot remain great if it betrays it allies and lets down its friends.

Honor is not necessarily victory, but an honorable peace is certainly not surrender. Key to that notion of honor was getting the North Vietnamese to go through the rituals of international diplomacy, such as publicly signing an agreement, promises (even if they were not believed) of a cease-fire, assurances that the ultimate reunification of Vietnam would occur through democratic means, and the like.

A fifth war aim, unspoken, was the preserving the president’s personal reputation for toughness. During the hottest phase of the Cold War as American presidents countered communist aggression in Korea, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia and elsewhere in Southeast Asia, none wanted to be on duty during another “loss,” like the fall of China during the Truman administration. A number of scholars have made the persuasive claim that vindicating the personal credibility, toughness and leadership of individual presidents was a driver for continuing the war.

The Democratic Party was stained with the loss of China, and Kennedy and Johnson did not want to be seen as soft. They felt their credibility as tough leaders and negotiators was crucial in maintaining the global balance of power. Nixon wanted to maintain his reputation for toughness, extending back to his days as an anti-communist in Congress, because he believed it was crucial for getting an honorable deal on Vietnam.

One thing that drove Kennedy’s policies was his perception of his relationship with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev. From the beginning, Kennedy felt he had to portray toughness: “I have to show him that we can be just as tough as he is. I’ll sit down with him and let him see who he’s dealing with.”

Johnson biographer and former staffer, Doris Kearns Goodwin, writes:

I knew from the start, Johnson told me in 1970, describing the early weeks of 1965, that I was bound to be crucified either way I moved. If I left the woman I really loved—the Great Society—in order to get involved in that bitch of a war … I would lose everything. All my programs. All my hopes to feed the hungry and shelter the homeless … if I left the war and let the Communists take over South Vietnam, then I would be seen as a coward and my nation would be seen as an appeaser.

With Nixon, there are multiple elements at play, including his many years of public service in a changing political landscape, his grievances with the media, his symbiotic relationship with that tower of self-assurance Henry Kissinger, his psychology and ego, and his calculated strategy to appear a loose cannon in order to force Hanoi and its patrons in Moscow and Beijing to negotiate.

He told aide H.R. Haldeman: “I call it the Madman Theory, Bob. I want the North Vietnamese to believe I’ve reached the point where I might do anything to stop the war. We’ll just slip the word to them that, for God’s sake, you know Nixon is obsessed about Communism. We can’t restrain him when he’s angry—and he has had his hand on the nuclear button—and Ho Chi Minh himself will be in Paris in two days begging for peace.”

Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon, influenced by the domino theory, believed they were acting with just cause by supporting the self-defense of South Vietnam as well as the neutrality of Cambodia and Laos in the context of superpower rivalry and communist insurgency.

Three of the war aims they shared—contain communism, spread democracy and demonstrate resolve to foreign audiences—are limited, yet robust national security objectives with moral credibility.

What about national honor? No one wants to think that our sons, husbands, brothers and fathers died in vain at Hue, Khe Sanh and Hamburger Hill.

The U.S. did not go to war to vindicate its national honor; honor became a war aim that prolonged the war. Regardless of its psychological and emotional power, the concept of national honor is morally perilous because it suggests additional cost and sacrifice not in pursuit of victory, but to simply continue the fight: “no cost too great.” The extreme view of national honor does not accord with the individualistic, democratic sentiments of the U.S. because it can become the voice of Hitler and the kamikazes.

Nonetheless, a focus on honor can become a factor restraining other war aims. We want presidents and generals to say: We will fight hard to win. We’ll give your sons and daughters in uniform every tool to be successful. We’ll care for them while in uniform and after they come home. And, we promise you, that if the calculus for fighting this war changes in some way, we will honor their service and your sacrifice by changing course. We won’t dishonor the dead by needlessly adding more to their numbers. That is a formula for peace with honor.

Finally, the fifth aim. A leader’s concern for glory does not mean that other war aims are necessarily tainted, but personal ego can have harmful effects on decisions by damaging the relationships among senior leaders (elected officials not trusting military commanders), limiting the possibilities for diplomacy and distorting the policy possibilities.

During the Vietnam era, the conditions Truman faced in Southeast Asia in the early 1950s evolved dynamically to the moments when President Gerald R. Ford watched the abandonment of the U.S. Embassy in Saigon on his television set in 1975. The decisions made across presidencies to fight and prolong the war had some sound strategic and ethical foundations, and yet there are morally troubling aspects to the war.

Just War Criteria

Jus ad bellum (moral justifications for going to war, why a war is fought)

1. Legitimate authority: Supreme political authorities are morally responsible for the security of their constituents and therefore are obligated to make decisions about war and peace.

2. Just cause: Self-defense of citizens’ lives, livelihoods and way of life are typically just causes; more generally speaking, the cause is just if it rights a past wrong, punishes wrongdoers or prevents further injury.

3. Right intent: Political motivations are subject to ethical scrutiny; violence intended for the purpose of order, justice and ultimate conciliation is just, whereas violence of hatred, revenge and destruction is not just.

4. Likelihood of success: Political leaders should consider whether or not their actions will make a difference in real-world outcomes. This principle is subject to context and judgment because it may be appropriate to act despite a low likelihood of success (e.g. against local genocide). Conversely, it may be inappropriate to act due to low efficacy despite the compelling nature of the case.

5. Proportionality of ends: Does the preferred outcome justify, in terms of the cost in lives and material resources, this course of action?

6. Last resort: Have traditional diplomatic and other efforts been reasonably employed in order to avoid outright bloodshed? Jus in bello (moral conduct during war, how a war is fought)

7. Proportionality: Are the battlefield tools and tactics employed proportionate to battlefield objectives?

8. Discrimination: Has care been taken to reasonably protect the lives and property of legitimate noncombatants?