George Armstrong Custer’s 1873 clashes along the Yellowstone River with Sioux warriors under Sitting Bull were harbingers of the disastrous 1876 fight on the Little Bighorn—except for the casualties.

Custer estimated his 7th U.S. Cavalry killed more than 40 American Indians, though the Indians themselves claimed only three wounded and none killed. Custer lost a half-dozen enlisted men killed, a handful wounded and one officer crippled for life. Also killed were two civilians who had accompanied the expedition.

The murders of regimental veterinarian John Honsinger and sutler Augustus Baliran sparked bitter enmity between confessed killer Lakota warrior Rain-in-the-Face and the Custer brothers—especially Tom Custer.

RESPECTED VETERINARIAN

Born in Germany around 1818, John Honsinger had served as a veterinarian with Union forces during the Civil War and, according to Samuel J. Barrows, a New-York Tribune journalist embedded with the 1873 expedition, “was greatly esteemed by officers and men for his personal and professional qualities.”

In wartime he received the pay of a first lieutenant—$75 a month. Honsinger was living as a civilian in Adrian, Mich., with wife and children, when on May 14, 1869, he accepted a post as senior veterinary surgeon of the 7th Cavalry at $100 a month.

In February 1873 the Army transferred the 7th Cavalry from Reconstruction duty in the deep South to the northern Plains. Honsinger traveled with the 10 companies under Lt. Col. George Custer to Yankton, Dakota Territory, where after a severe winter the outfit was ordered north that June to Fort Rice to join Colonel David Stanley’s Yellowstone Expedition, escorting surveyors for the Northern Pacific Railroad westward along the river. Barrows rode alongside Honsinger, describing him as “a fine-looking, portly man, about 55 years of age, dressed in a blue coat and buckskin pantaloons, mounted on his fine-blooded horse.”

A description of Augustus Baliran surfaced in an 1896 letter written by Captain Frederick Benteen to fellow 7th Cavalry veteran and Little Bighorn survivor Private Theodore Goldin:

“At Memphis, Tenn., Baliran was a proprietor of a restaurant and gaming establishment, doing a good business, and a gambler by profession.…[As Baliran had] some money, Custer induced him to come with the 7th Cavalry as sutler, telling him the officers of the regiment were high players, and he could make a big thing, ‘catch them coming and going.’ Baliran told all this to [Lt. Charles] DeRudio on ’73 trip, and DeRudio told me Custer had put in 0 but had drawn out to that time $1,000. A few weeks thereafter Baliran and old veterinarian Honsinger were killed. What became of the effects of the firm I never heard.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

While Benteen was certainly no fan of Custer, the letter begs an intriguing question: After 1870 the War Department had limited each post to one sutler, appointed and licensed by Secretary of War William Belknap, an arrangement that prompted a notorious kickback scheme. But who had brought Baliran to Belknap’s attention?

Benteen also told Goldin of an episode involving Baliran that exposed friction between Stanley, an alcoholic, and his upstart junior officer Custer, a teetotaler. In late July, after Stanley went on a three-day bender, his loyal officers decided to destroy Baliran’s supply. Appreciating the potential cost to the sutler, Lt. Col. Frederick Grant—eldest son of President Ulysses S. Grant, who had been detailed to join the expedition—moved Baliran’s stock into the regimental grain wagons and the grain into the sutler’s wagons.

Custer was oblivious. But Stanley’s men kept searching, found Baliran’s cache and reportedly “split the good red liquor on the alkaline soil of Montana.” When Baliran complained, an enraged Custer pointed the finger at Stanley, who was equally oblivious and indignant. For his part, Benteen managed to furtively snatch up a bottle.

As the column entered Yellowstone country, one wonders whether Dr. Honsinger and sutler Baliran appreciated the danger. The Hunkpapa Lakotas—aka “Sitting Bull Sioux”—regarded the land under survey as theirs by right of the Sioux Treaty of 1868, signed at Fort Laramie in the wake of Red Cloud’s War. They were prepared to fight for it.

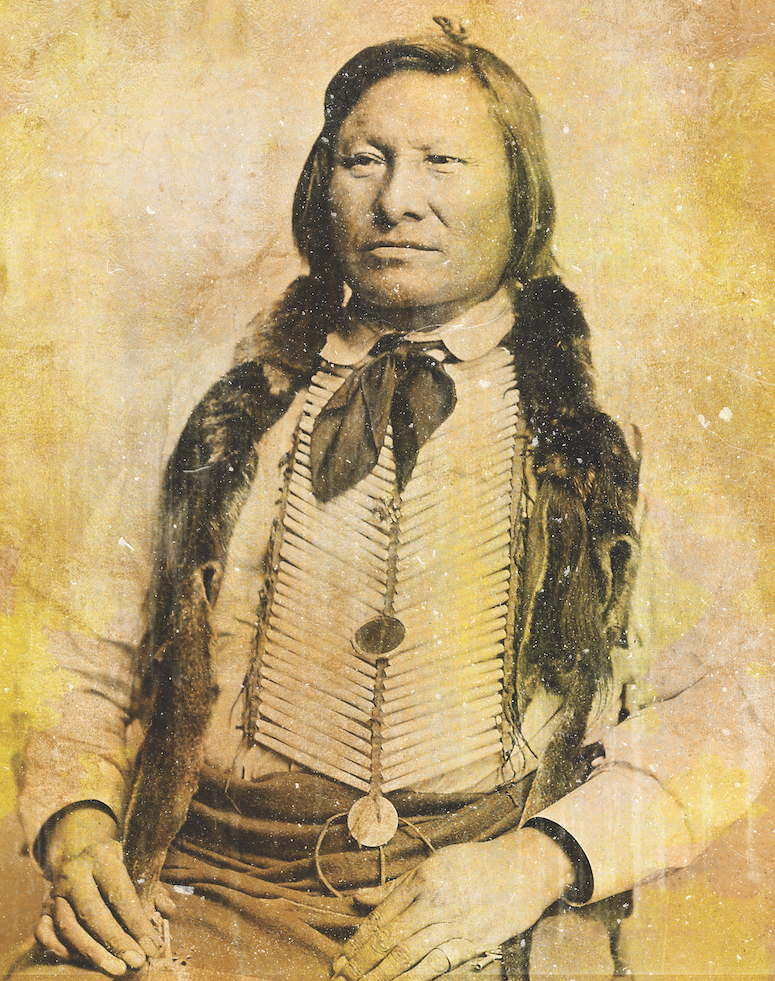

Rain-in-the-Face had secondary, more drastically romantic motives for wanting to kill soldiers. He described the circumstances in an impromptu 1894 interview with writer W. Kent Thomas at Coney Island, N.Y.:

“I was a great fellow with the girls. They used to tease me to get me mad—when I got mad I knew no reason; I wanted to fight. One night a girl dared me to go up to Fort [Abraham] Lincoln and kill a white man. I told her it was too risky.…She said: ‘A brave man fears nothing. If you are a coward, don’t go. I’ll ask some other young man who isn’t afraid.’

…The other girls laughed, but the young men who heard it didn’t. They feared me. I would have killed them for laughing. I went to my lodge and painted sapa [black, the death color], took my gun, my bow, my pony. Sitting Bull had forbidden anyone to leave camp without his permission. I skipped off under cover of darkness and went up to Fort Lincoln. I hung around for two days, watching for a chance.…I wanted to carry back the brass buttons of a long sword to the girl who laughed at me.”

RAIN BIDING HIS TIME

Rain missed his chance at the fort. But he bided his time. On Aug. 4, 1873, as Stanley’s column of 1,300 soldiers and 27 scouts made its way west along the river in Montana Territory (near present-day Miles City), it unwittingly approached a camp of some 500 Sioux and Cheyenne warriors under Sitting Bull and Gall. Riding several miles ahead of the column was an advance command of 86 soldiers under Custer, with Captain Myles Moylan as subordinate commander.

Custer’s brother, 1st Lt. Thomas Custer, led one company of men, 2nd Lt. Charles Varnum another. Rounding out the officers was 1st Lt. James Calhoun, the Custers’ brother-in-law.

Halting his men at a cottonwood grove beside the river, Custer had them picket their horses and rest as they waited for the column. They roused from their slumber when a half-dozen American Indians threatened to run off their horses.

Custer himself had set out in a wary pursuit when some 250 Sioux broke from the woods, turning the hunter into the hunted. Following on his brother’s heels, Tom Custer came to the rescue, his 20 men dismounting to form a skirmish line that held off the Indians as Moylan brought up the stragglers. The troopers then backed into the protective grove and fought the Indians with long-range fire for about three hours in 110-degree heat.

Meanwhile, back in Stanley’s main column, Honsinger and Baliran sauntered off toward the river, apparently to water their horses. “No man in the regiment took more care of his horse than [Honsinger],” recalled Barrows. “It was an extra-professional care—a love of the horse for his own sake, without which no man ought to be a cavalryman, much less a veterinary surgeon.

He had taken the horse at Yankton, in the spring, from one of the cavalry troops—a gaunt-looking steed then, but under his fostering care he had grown fat and sleek.” Spotting distant riders, a keen-eyed Arikara scout with the Stanley column grabbed Honsinger’s bridle and warned the veterinarian, “Indians, Indians.”

“No, no,” Honsinger answered, “they are cavalry, cavalry.” Waving off the scout, he and Baliran, who was mounted on a tough little Mexican pony, rode on.

A VIOLENT AMBUSH

Private Benjamin Brown and other troopers had independently ridden ahead of the column to fill canteens in the Yellowstone. Honsinger and Baliran had arrived just upriver when shots broke the bucolic peace. Brown later recounted his memory of events:

“I saw Mr. Baliran, the regimental sutler, and Mr. Honsinger, the veterinary surgeon, ride up to a large grove a short distance up the river from where I was.…I thought I would wait until the wagon train came in sight, so laid down near my horse and must have dropped into a light sleep, when suddenly I was startled by yells from the large grove above.

I jumped up and went out a few steps to where I could see, when I was horrified to see a number of Indians killing Mr. Baliran and Mr. Honsinger. Mr. Baliran was running on foot, and two Indians were shooting arrows into his back; Mr. Honsinger, also on foot, was running, and a big Indian rode up and struck him over the head with the stock of his gun.”

“One morning I saw the sutler and a horse medicine man go out to a spring,” Rain-in-the-Face recalled for Thomas two decades later. “I rushed up and shot the sutler and brained the horse medicine man with my war club; then I shot them full of arrows and cut off some buttons.”

Pvt. John H. Ball, mounted on his horse and leading another up from the river, rode for his life, but other warriors quickly chased him down and shot him from the saddle. (Soldiers didn’t find his body until their return that September. By then it had been picked to the bone.)

Brown leaped on his horse bareback and galloped full tilt back to the column, shouting, “All down there are killed!”

Stanley heard the shots and Brown’s hysterics and ordered his troopers in pursuit of the Indians. Second Lt. Charles Braden led the advance unit. Cresting the steep bluff overlooking the river, Braden and his troopers had to dismount and lead their horses down. As they did, Rain-in-the-Face and a half-dozen other Lakotas passed 100 yards in front of them.

Rain, who mistook the approaching officer for Custer, made good his escape. “I didn’t have time to scalp the men I got,” he later said. “I jumped on my pony and yelled at them to catch me.” He claimed the soldiers chased him some 25 miles before they gave up. In their haste, the fleeing Sioux shot all of their spare horses, including Honsinger’s prized thoroughbred, once restored to health under the veterinarian’s skilled and loving care. “[Honsinger] had died a victim to his devotion to that noble horse,” Barrows eulogized.

DEAD WITH EYES OPEN

“When Mr. Baliran was found, there was an arrow run clear through his body and into the ground, and he had hold of it with his right hand, his eyes open,” Brown recalled. “Honsinger’s left hand was at his head as he fell, and [he] was brought into camp in that way.” The Lakotas had rifled the dead men’s pockets, taking the sutler’s money and the doctor’s pocket watch. As for the buttons Rain had cut from their coats, the warrior later claimed, “[The girl] sewed them onto her shawl.”

That evening, after sewing the bodies into canvas sleeves, soldiers buried them at the base of the bluff later named for Honsinger. The men then picketed their horses on the site to erase all signs of the grave.

After another skirmish—during which Braden took a crippling gunshot wound to the thigh before the column drove the Indians from the field—the Yellowstone Expedition fell apart, not through any failure of Colonel Custer’s, but because the Northern Pacific had gone bankrupt in the deepening financial Panic of 1873.

Meanwhile, Col. Stanley heard from a man who had bought Dr. Honsinger’s saddle from Rain-in-the-Face and urged headquarters to have him arrested. No action was forthcoming.

In December 1874 Custer learned from scout “Lonesome” Charlie Reynolds that Rain was strutting about the Standing Rock Agency trading post, boasting of having killed the horse doctor and the sutler.

The colonel resolved to take matters into his own hands. Under the ruse of tracking down troublesome horse thieves, Custer dispatched brother Tom and Capt. George Yates to Standing Rock with 100 men to arrest Rain. Arriving at the trading post, Lt. Custer and five picked men strode through the door and approached Rain. As the Lakota lowered a blanket from around his ears in the intense cold, Tom sprang forward, wrapped his arms around Rain and threw him to the floor. The arrest may not have been exactly clean.

“I saw Tom Custer kick and slap Rain while troopers held him a prisoner,” recalled Frank Huston, a notorious ex-Confederate squaw man. “I got out of the post trader’s before they came back to get me.”

“Little Hair [Tom Custer] had 30 long swords there,” Rain-in-the-Face told Thomas. “He slipped up behind me like a squaw when my back was turned. They all piled on me at once; they threw me in a sick wagon [ambulance] and held me down till they got me to the guardroom at Lincoln.”

Back at the fort Colonel Custer interviewed the captured Lakota through an interpreter. Elizabeth Custer wrote a presumably secondhand account of Rain’s interrogation:

“[The colonel] spent hours trying to induce the Indian to acknowledge his crime. The culprit’s face finally lost its impervious look, and he showed some agitation. He gave a brief account of the murder and the next day made a full confession before all the officers. He said neither of the white men was armed when attacked. He had shot the old man [Honsinger], but he did not die instantly, riding a short distance before falling from his horse. He then went to him and with his stone mallet beat out the last breath left.

Before leaving him, he shot his body full of arrows. The younger man [Baliran] signaled to them from among the bushes, and they knew that the manner in which he held up his hand was an overture of peace. When he reached him, the white man gave him his hat as another and further petition for mercy, but he shot him at once, first with his gun and then with arrows. One of the latter entering his back, the dying man struggled to pull it through. Neither man was scalped, as the elder was bald, and the younger had closely cropped hair.”

RAIN IN CHAINS

Iron Horse, one of Rain’s six brothers, soon arrived at the fort to bid farewell. Libbie Custer picked up the story:

“[The colonel] sent again for Rain-in-the-Face. He came into the room with clanking chains and with the guard at his heels. He was dressed in mourning. His leggings were black and, and his sable blanket was belted by a band of white beads. One black feather stood erect on his head. Iron Horse supposed that he was to be hanged at once, and that this would be the final interview.”

Ten days later Iron Horse returned at the head of a large, fully armed party of warriors, who soon packed into the post headquarters, seeking a council. Custer invited his wife and other ladies of the post to the lounge to look them over.

“The Indians,” Libbie recalled, “turned a surprised, rather scornful glance into the ‘ladies gallery.’ In return for this we did not hesitate to criticize their toilets [appearance]. They were gorgeous in full dress…simply superb.”

A manacled Rain soon shuffled in, and Iron Horse launched into a speech, beseeching Custer to spare his brother’s life. Two young warriors then asked permission to join Rain in the guardhouse, which they did.

“I could not help recalling what someone had told me in the East,” Libbie reflected, “that women sometimes go to the state prison at Sing Sing and importune to be allowed to share the imprisonment of their husbands or brothers. But no instance is found in the history of that great institution where a man has asked to divide with a friend or relative the sufferings of his sentence.”

‘I WOULD CUT HIS HEART OUT’

After the young warriors returned to the reservation, Rain had another visitor: Tom “Little Hair” Custer. In retrospect, his rage against the Lakota seems out of proportion to what was ostensibly an act of war. Perhaps Tom, an alcoholic unlike brother George the teetotaler, missed the liquor Baliran had slipped him on the sly whenever the family urged him to quit drinking.

“I was treated like a squaw, not a chief,” Rain told Thomas. “They put me in a room, chained me, gave me only one blanket. The snow blew through the cracks and onto me all winter. It was cold. Once Little Hair let me out, and the long swords told me to run. I told Little Hair that I would get away sometime.…When I did, I would cut his heart out and eat it.”

Then Rain-in-the-Face did get free. “I was chained to a white man,” he recalled. “One night we got away. They fired at us, but we ran and hid on the bank of Hart River in the brush. The white man cut the chains with a knife [file]. They caught him next day.”

“I was one of the bunch that helped Rain escape from the guardhouse,” Frank Huston wrote Custer historian W.A. Graham, who found the squaw man credible. Rain told writer Charles Eastman that a sympathetic guard, “an old soldier,” had set them free, indicating he would fire into the air as they ran for it.

A DEATHBED CONFESSION

That “old soldier” may have been Cpl. William Teeman, who had served in the Royal Danish Army prior to immigrating. Teeman’s partially scalped body was found after the Battle at the Little Bighorn. The connection came to light in a letter from an anonymous 6th Infantry sergeant, published in the Aug. 1, 1876, New York Herald:

“Everybody was scalped and otherwise mutilated, excepting General Custer and Corporal Tiemann [sic], whose scalp was partly off, and who had the sleeve of his blouse with the chevron uplaid over it in a peculiar manner. This enabled a good many men of the 7th Cavalry…to detect one of the participants on the Indians’ side in the presence of Rain-in-the-Face, who was in the guardhouse last winter and chained to a corporal, also a prisoner at the time.

In confessing to having killed Honsinger and Baliran, Rain supplied details similar to those of eyewitness Pvt. Brown and consistent with the descriptions of both bodies. Indeed, he never denied it. He long denied having killed George Armstrong Custer at the Little Bighorn, likely out of respect for Libbie.

But after converting to Christianity, he made a deathbed confession to Congregational Church missionary Mary Collins: “Yes, I killed him,” he said. “I was so close that the powder burnt his face.” The forensic evidence suggested otherwise, as George Custer’s face bore no powder burns.

When Collins asked whether Rain had killed Tom Custer, who died alongside George at the Little Bighorn, Rain denied having even seen him. But perhaps the elderly Lakota had confused the Custer brothers. According to Lieutenant Charles Roe, who helped bury bodies after the battle, someone had cut out Tom’s heart.

Collins asked Rain if he’d done that. “No,” he answered, “I did not have time. I was busy killing, and when we had killed all, we ran away.” After the battle soldiers scouring the Indian village reportedly found a human heart tied to a lariat. While the Lakotas mutilated enemy dead, they were never known to be cannibals.

John Koster, who writes from northern New Jersey, is the author of Custer Survivor and wrote “Right as Rain-in-the-Face,” in the June 2014 issue of Wild West. Recommended for further reading: “Indian Fights and Fighters,” by Cyrus Townsend Brady, and “The Custer Myth,” by W.A. Graham.

This article originally appeared in the April 2017 print edition of Wild West.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.