America’s burgeoning industrial capacity inspired numerous military inventions

The United States was on the cusp of becoming an industrial giant when the Civil War burst into flame in 1861. The local, cottage-industry system was already on its way out as railroads, canals, and steamboats brought goods manufactured in industrial centers to remote parts of the country. Take the steamboat Arabia that hit a snag and sank in the Missouri River near Kansas City, Mo., in 1856. Her cargo, headed for the frontier and preserved in a museum in the same city, was an Amazon-like potpourri of just about everything a settler would need, hardware, tools, food, and clothes, the list could go on. No need to weave cloth or forge a hammer. Just get to work. In such an industrially charged atmosphere, it’s no surprise that the war inspired many to get to work designing military items that provided comfort or killing power. What is surprising is the varied background of the designers, and the wide range of items they produced. Some succeeded, and others underwhelmed. The following is a small sample of the designs of war.

[hr]

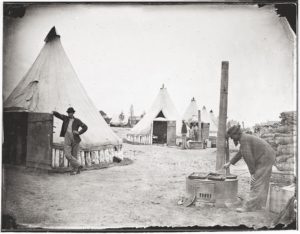

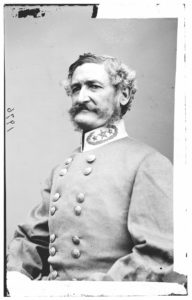

Forfeited Fortune

In 1856, Henry Hopkins Sibley designed a teepee-like canvas tent for use in the field by the U.S. Army. His design differed from other bell tents in that its center pole was secured by a supporting tripod, eliminating the need for easily tangled guy ropes and pegs. The collapsible tripod system made the canvas tent and its components easier to store and transport than its predecessors. The conical tent stood about 12-feet high and 18-feet in diameter and could comfortably house about a dozen men, and the U.S. Army used the tent during the winter of 1857–58 Utah Expedition. Sibley later designed a similarly conical-shaped metal stove that could be used to heat the tent and for cooking. The easy-to-use and transport Sibley tent and its corresponding stove were an economical choice for the Army when it suddenly found itself with tens of thousands of men to house at the outset of the Civil War. Nearly 44,000 of the pair were ordered for use during the conflict. In 1858, Sibley had patented both inventions as a member of the U.S. Army and was contracted to receive a $5 royalty for each item produced. His would-be fortune was forfeited, however, in 1861 when he resigned to fight for the Confederacy.

In 1856, Henry Hopkins Sibley designed a teepee-like canvas tent for use in the field by the U.S. Army. His design differed from other bell tents in that its center pole was secured by a supporting tripod, eliminating the need for easily tangled guy ropes and pegs. The collapsible tripod system made the canvas tent and its components easier to store and transport than its predecessors. The conical tent stood about 12-feet high and 18-feet in diameter and could comfortably house about a dozen men, and the U.S. Army used the tent during the winter of 1857–58 Utah Expedition. Sibley later designed a similarly conical-shaped metal stove that could be used to heat the tent and for cooking. The easy-to-use and transport Sibley tent and its corresponding stove were an economical choice for the Army when it suddenly found itself with tens of thousands of men to house at the outset of the Civil War. Nearly 44,000 of the pair were ordered for use during the conflict. In 1858, Sibley had patented both inventions as a member of the U.S. Army and was contracted to receive a $5 royalty for each item produced. His would-be fortune was forfeited, however, in 1861 when he resigned to fight for the Confederacy.

[hr]

It Bombed

The Ketchum Grenade looks like it was designed by a cartoonist. The actual inventor, however, was William Ketchum, a former mayor of Buffalo, N.Y., from 1844 to 1845. His weapon consisted of a conical iron body with a plunger, and a stick with fins inserted into the opposite end of the body to provide aerodynamics. To arm the grenade, which came in 1-, 3-, and 5-pound versions, the user pulled out the plunger, inserted a percussion cap into the body, and replaced the plunger. Black powder was poured into the hole of the base, and the fin stick was firmly shoved in to seal the hole. The grenade was then ready to lob at the enemy. If things went well, the plunger hit a hard surface and the bomb detonated. But things often didn’t go well. Just arming the grenade was a cumbersome process, and it often landed on its side and failed to explode. Nonetheless, Ketchum’s grenade, patented on August 10,

1861, was used by the Union Army at Vicksburg, Petersburg, and other sieges with mixed success. During a Union charge on the Confederate works at Port Hudson, La., in July 1863, Southern troops softly caught the grenades in their blankets and tossed them back at their attackers.

[hr]

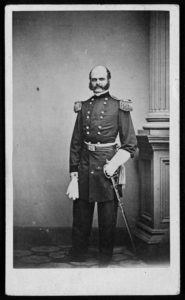

Burnside’s Breechloader

In the mid-1850s, well before his stint as the commander of the Army of the Potomac, Ambrose E. Burnside designed and patented the .54-caliber Burnside Carbine. The breechloader was designed to give mounted troops a light and quick-loading weapon. When a latch connected to the trigger guard was pressed down, the breech block dropped open and allowed the user to insert a cartridge, which was also unique and invented by Burnside. The conical cartridge, containing powder and a

bullet, was dropped base first into the breechblock. The trigger guard was then raised, forcing the bullet into the breech of the barrel. A raised brass ring on the cartridge sealed the breach and eliminated the tendency to leak hot gas that most breechloading guns suffered from. When the trigger was pulled, a conventional percussion cap was used to create a spark that burned through a hole in the base of the cartridge. The U.S. government didn’t show much interest in the gun at first, but orders exploded with the onset of the Civil War. More than 55,000 were ordered for use by Union cavalrymen. It was the second most popular carbine used during the war, and saw action in all theaters. The Burnside Carbine was manufactured in Rhode Island by the Bristol Firearms Company and later, the Burnside Rifle Company, from about 1857 to 1865.

[hr]

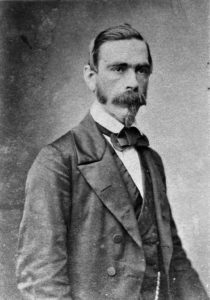

The Burton Ball

Henry Burton’s redesign for a French captain’s bullet occurred just in time for the Civil War, and his mass-produced version of the “Minié Ball” maimed thousands of Americans and put thousands more in their graves. Burton was the acting master armorer of the Federal Arsenal in Harpers Ferry, Va., during the 1850s when he rethought the slug developed by French Captain Claude-E’tienne Minié in 1849. The French officer’s bullet was conical instead of round, and made slightly smaller than the diameter of a musket’s barrel with a hollow base that could expand when the gun was fired to catch the rifling. For the first time Minié’s bullet allowed for the rapid loading of rifled weapons that formerly had been so slow to load that only special riflemen could use them while the rank and file carried smoothbores. But the French version required a small metal plug that was forced up into the bullet upon firing, an extra step that slowed production. Burton’s concept, adopted by the U.S. Army in 1855, omitted the plug, which allowed the bullets to be swaged in mass quantities. Burton also thinned out the base, which was encircled by three rings meant to hold a lubricant to ease loading and also catch the rifling.

[hr]

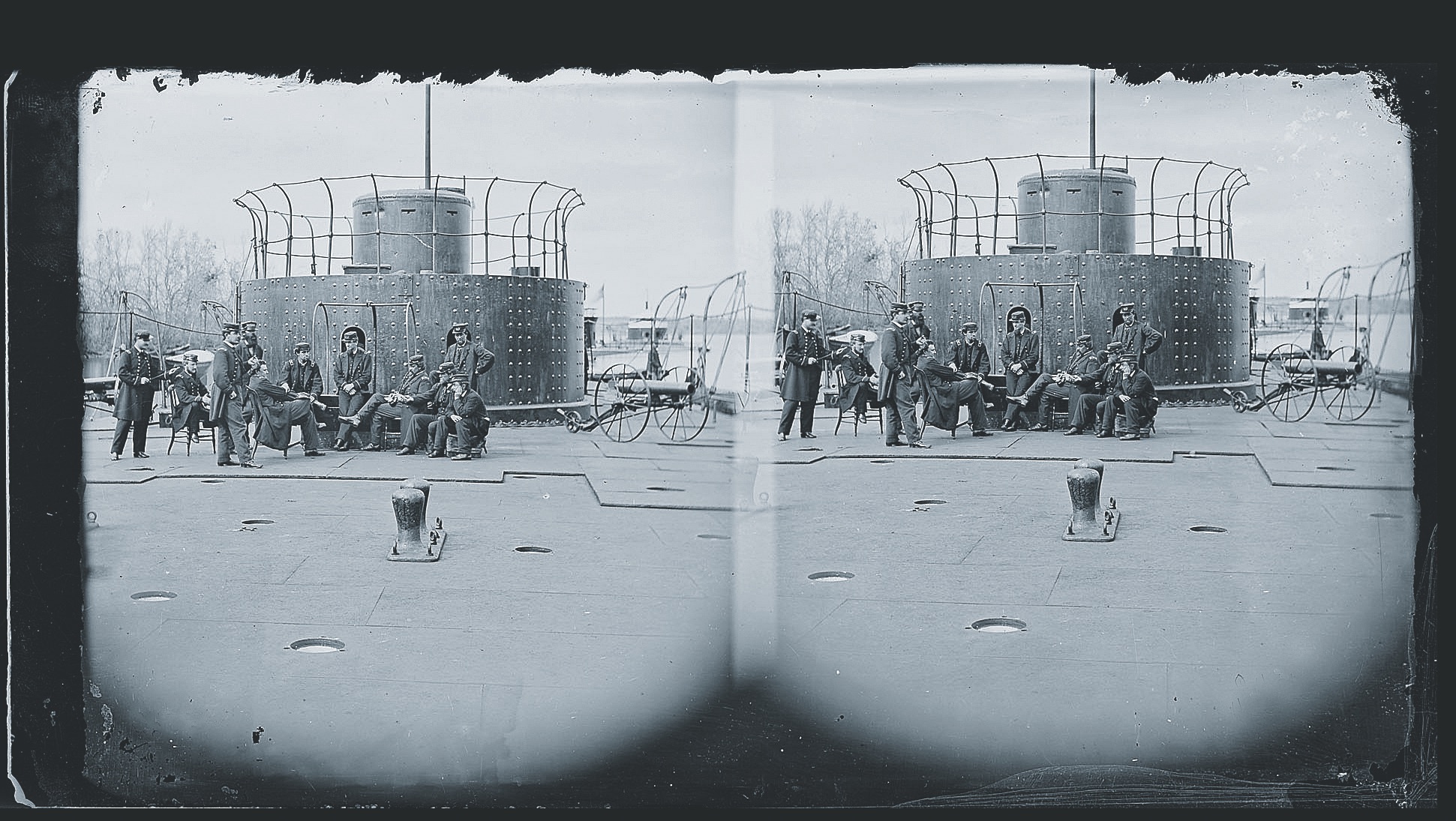

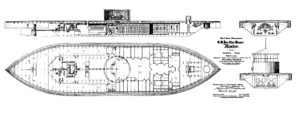

Cheesebox on a Raft

Monitor, published in 1862, shows the ship’s inboard profile and hull cross sections through the engine and boiler spaces. (U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command)

When the Federal high command caught wind in mid-1861 that Confederates were converting the captured USS Merrimack to an ironclad, the Union’s desire to have armored vessels on the water became urgent. Swedish-born inventor John Ericsson firmly believed that victory in the Civil War “will rest upon the side which holds possession of the seas.” On August 29, 1861, he submitted to President Abraham Lincoln his plan for a “subaquatic ironclad vessel with a gun turret.” The ship’s unique design, distinguished most notably by its revolving turret, garnered many snickers and doubts from concerned government officials, but on October 4, 1861, a contract was issued to Ericsson for “an ironclad, shot-proof steam battery.” It specified that the vessel must be provided with masts and sails and that it should make 6 knots under sail and 8 knots under steam. It was also agreed ‘that said vessel and equipment in all respects shall be completed and ready for sea in 100 days from the date of this indenture.’ Ericsson did not disappoint. The USS Monitor was launched on January 30, 1862, from the Continental Iron Works in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, N.Y. On March 9, 1862, it came head to head with the Virginia and the world took note. Even decades later, in 1937, Winston Churchill wrote, “The combat of the Merrimac and the Monitor made the greatest change in sea-fighting since cannon fire by gunpowder had been mounted on ships about four hundred years before.”—D.B.S. and M.A.W

This story appeared in the June issue of Civil War Times.