In the early morning hours of June 6, 1944, U.S. Army Technician 5th Grade John Joseph “Joe” Pinder Jr. rode on a rough sea toward the Normandy coast in a landing craft, trying to keep his footing on the slippery metal deck. It was a strange place for the dark-haired Pennsylvanian to spend his 32nd birthday, but Pinder’s life had already taken plenty of turns. Just a few years earlier he’d been a minor-league baseball pitcher with a decent fastball and a deft curve, plying his trade in small-town ballparks in Florida and Alabama and Georgia in hopes of earning a shot at the majors. Now, he was headed for the place code-named Omaha Beach, where he and thousands of other American soldiers were about to descend into a cold, wet, man-made hell of buried mines, barbed wire, spike-studded barriers, and machine-gun fire.

Pinder had other things on his mind as well. Back in Greenville, Alabama, where he’d pitched, his fiancée, Ruby, was waiting for him. And in his wallet he carried a photograph of his younger brother, Harold. On January 29, 1944, Hal had been shot down as he flew a B-24 over Belgium, and he was listed as missing in action. Pinder had written to his parents that he remained hopeful that Hal was still alive, even if he was languishing in a Nazi POW camp. If the Allies could win the war, Hal would be freed. Now, though, Pinder and the other GIs had to take Omaha Beach. Pinder’s job in the initial wave of the invasion force was to set up the radio equipment that would help successive waves of troops land on the beach and overwhelm the German defenses.

But first they had to get ashore. As the landing craft approached the beach, where the Germans had planted Czech hedgehogs as a defensive measure, the boat suddenly came under heavy enemy gunfire. Bullets pierced its thin hull and ricocheted inside, tearing into soldiers’ bodies. Just as the craft reached the surf breaking onto the beach, a German shell punched a hole in the side of the craft, the impact almost causing it to flip over. Ice-cold water gushed in.

Just then, the landing ramp opened, and soldiers jumped into the waist-deep water, dragging the wounded men with them. In the terror and confusion, some dropped their weapons and their backpacks, and the unit’s bulky ship-to-shore radios—crucial to the invasion—were left behind.

Except for one set. Pinder somehow managed to hoist his SCR-284 radio set—at 55 pounds, about the size of a small air-conditioner—onto his shoulder and balance it as he staggered forward and climbed down into the water. The shore was a football field away. He’d only gotten a few yards from the landing craft when a hunk of shrapnel tore into the left side of his face. Head down, he put one foot in front of the other and waded on.

More than 500 major league baseball players served in the U.S. military during World War II, including such stars as pitcher Warren Spahn, who left the Boston Braves in 1942 to enlist in the army and fought in the Battle of the Bulge and the Battle of Remagen. Many were deliberately kept away from the fighting, assigned instead to play exhibition games to entertain troops headed for the battlefield. At the same time, countless minor league players ended up in combat. In some ways, they may have been better prepared for war, because the perseverance and determination they needed to nurture their big-league dreams became immensely useful attributes in the life-and-death contest in which they were now competing.

Joe Pinder was the epitome of that sort of ballplayer—an athlete who spent most of his playing career in Class D, the lowest level of the professional hierarchy, where as a right-handed pitcher he was a solid performer who showed occasional flashes of greatness. He was born in 1912 in McKees Rocks, a town along the Ohio River near Pittsburgh, to steelworker John Pinder and his wife, Laura. The Pinder family later moved about 40 miles away to the town of Butler, where Joe grew up, graduating from Butler High School in 1931 as the valedictorian of his class.

But Pinder’s real love was baseball, and he spent a few years after graduation pitching for amateur sandlot teams. Then, in 1935, he signed a contract with the Butler Indians, a new Class D minor-league team. In his first season, he took the mound in eight games, posting a 3–2 record with a 3.33 earned-run average, according to an article by baseball historian Gary Bedingfield, the author of two books on players who fought in World War II.

The following season, the Butler Indians joined the New York Yankees farm system. Pinder got to pitch in an exhibition game against the Negro League’s Pittsburgh Crawfords, whose lineup included hard-hitting catcher Josh Gibson. The Crawfords won the game in a rout, but in what was probably one of Pinder’s proudest achievements as an athlete, he twice retired Gibson, once on a fly ball and once on a grounder. Despite that impressive performance, the Butler team released him a few weeks later.

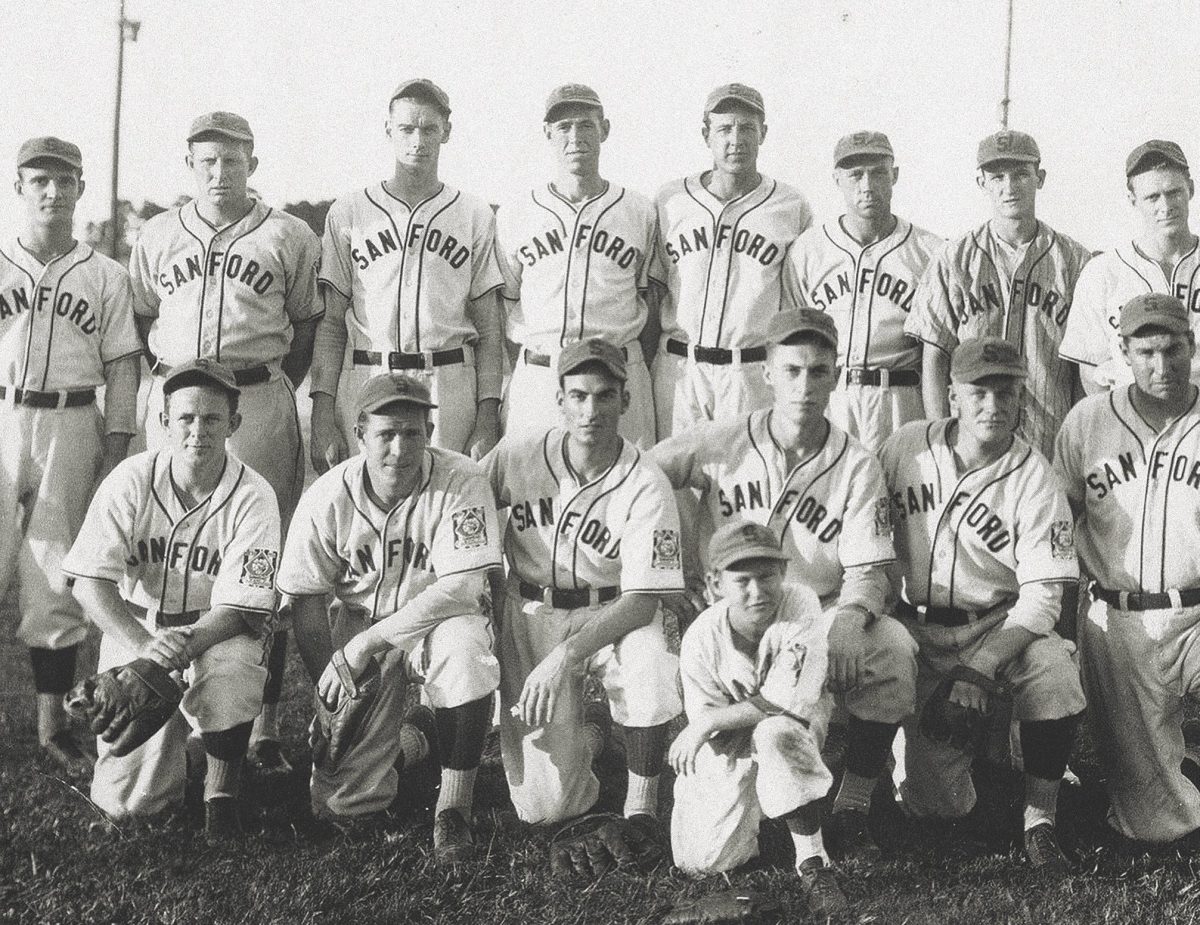

Two years later, in 1938, Pinder tried out for the Sanford Lookouts, a Class D team in Florida affiliated with the Chicago White Sox, and made its roster. His record that season with the cellar-dwelling team was a woeful 9 wins against 18 losses, but he had a few bright moments, including pitching a pair of one-hit games. A local sportswriter praised his curve and fastball and wrote that he had the heart to make it to the majors.

Pinder again played for the Lookouts in 1939, and this time had the best season of his brief baseball career, with 17 wins against seven losses, and a 3.92 ERA. The following season, 1940, he started with Sanford but then moved up for a brief time to the Macon (Georgia) Peaches, a Class B team, before he returned to Florida to play for another Class D team, the Fort Pierce Bombers.

“His ambition is to become a major league player,” a local sportswriter observed, “and without any flowery ado he will tell you that his whole life is based on reaching the top in pro ball.” That year Pinder had 11 wins and nine losses and then was optioned by the Greenville Lions, a Class D team in Alabama, where he went 6–2 and achieved the unusual distinction of starting both games of a doubleheader, according to baseball historian Dick Thompson. In his final game he led his team to a 7–1 win over the Tallahassee Indians.

It was the last time Pinder would pitch in the minors. In January he was inducted into the army, about the same time his younger brother, Harold, enlisted in the Army Air Force.

As a member of the storied 1st Infantry Division, better known as The Big Red One, Pinder saw action in North Africa and Sicily. In July 1943, near Gangi, Sicily, he showed his courage by remaining at an exposed observation post that was under artillery and mortar attack so that he could keep transmitting information to the regimental command post. His Bronze Star citation for that action noted that “his heroic devotion to duty was instrumental in the capture of an important objective.”

In the fall of 1943, Pinder was sent to England, where preparations were underway for the Allied invasion of France. There he was able, for the first time in two years, to reunite with Harold, a first lieutenant in the 6th Squadron, 44th Bombardment Group (Heavy), at Shipdham. It would be their last meeting. A few months later, Harold Pinder, in his 10th bombing mission, flew the B-24H Sky Queen over Frankfurt, Germany. In the skies above Belgium, a German Focke-Wulf 190 shot him down.

According to Bedingfield, the younger Pinder survived the crash, managed to hook up with Belgian resistance fighters, and evaded capture for more than two months. But that April, two months before the D-Day invasion, Harold was holed up in the cellar of a Belgian farmhouse when he heard the thud of a German grenade hit the floor, followed by a second one. Fortunately, neither went off. But Harold knew that his luck had run out, and German soldiers soon found him. He was sent to a prisoner of war camp.

Back in England, Joe Pinder knew only that his brother was missing in action. He went to his brother’s base and asked the other airmen if they knew anything about what had happened that day. They could only tell him that they’d seen the Sky Queen vanish in the clouds. Pinder wrote to his widowed father, expressing hope that Hal had been captured and was still alive. But the uncertainty about his brother’s fate still weighed on Pinder the morning of June 6, as he headed toward Omaha Beach.

When he was hit, Pinder stumbled and almost fell into the water. “The side of his face was left hanging and he could only see from one eye,” Sergeant Robert Michaud later recalled. “He held his hanging flesh with one hand and gripped the radio and dragged it to shore.”

Somehow he reached a pile of stones on the beach, where other members of his unit lay in the sand, gasping as they tried to catch their breath. Finally, Pinder was able to set down the precious radio set. Someone tried to get him to seek help from a medic, but he refused.

It was an astonishing feat just to make it to the beach with the radio in his condition. But Pinder must have known that wouldn’t be enough. The officers needed the rest of the equipment on the landing craft to set up a headquarters; without it the resulting chaos might cost more lives.

Before anyone could stop him, Pinder turned and ran back into the water. Wading out to the half-sunk craft, he picked up a second radio and other equipment and turned to wade back. With machine-gun fire whizzing around him, he staggered to shore again.

Pinder turned back once more. He got to the landing craft, grabbed more equipment and the code books, and plunged into the water again. This time a German gunner spotted him and took aim, firing a string of bullets. Water spouted around Pinder as the shots missed. But then a burst of fire caught him and tore into his leg. After falling into the water, Pinder struggled to his feet and staggered once again to the beach.

When he reached the soldiers in his unit, they saw his weakened condition and tried to help him. Pinder waved them off. He didn’t want a medic. Instead, he was focused on getting the radios set up and operational. He started hooking up the equipment, in the process exposing himself to more enemy fire. “He would not stop for rest or medical attention,” Captain Stephen Ralph, his company commander, later recalled. As Pinder kept working, another bullet hit him.

Although Joe Pinder did not survive the morning on Omaha Beach, his heroism helped make the invasion a success. With the equipment he retrieved from the landing craft, radio operators were able to communicate with the men in the navy destroyers’ gun turrets, talk to commanders offshore, and help guide successive waves of soldiers onto the beach. Ralph later cited Pinder’s “superhuman efforts” in his medal recommendation.

Six days later, Pinder’s father received the tragic news in the form of a terse, typewritten letter from the War Department that included no mention of Pinder’s heroism that day. But three months later, he received some consolation when he learned that Hal was still alive, in a German POW camp. “Joe died worrying about Hal,” Pinder’s father later told a reporter for the Pittsburgh Press. “Every letter home, he kept asking for him.”

But now the elder Pinder had to write to his youngest son and let him know that Joe had died. In a 1996 interview, Harold Pinder recalled that when he got the news in August 1944, he took it hard. Joe had been a good big brother to him, teaching him how to hunt and fish and play ball. “We could walk around a barbed-wire enclosure for exercise,” he recalled. “When I got the letter, I walked for a couple of hours.”

Joe Pinder was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor in a ceremony at a regimental armory in Baltimore on January 4, 1945, becoming one of a dozen Americans who earned the medal at Normandy. Pinder’s father attended the event and received the award from Major General Philip Hayes.

Harold Pinder, who on his liberation in 1945 was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross with Bronze Star, returned to the Pittsburgh area. He married and then briefly moved to Florida to work as a cargo pilot before he went back to Pennsylvania and embarked on a long career as a draftsman. He died at age 86 in 2008.

Joe Pinder’s body was eventually returned from France, and he was buried in a cemetery in Florence, Pennsylvania, where in 2000 a monument was dedicated in his honor. His family donated his medal to the Soldiers & Sailors Memorial Hall & Museum in Pittsburgh, along with some of his personal items—including Pinder’s wallet, which was recovered from Omaha Beach that day, with his brother’s picture inside. Those mementos serve as a reminder of an athlete who died young, but not before putting on his greatest, bravest performance.

Patrick J. Kiger is an award-winning journalist who has written for GQ, the Los Angeles Times Magazine, Mother Jones, Urban Land, and other publications.

This article appears in the Winter 2020 issue (Vol. 32, No. 2) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: War Stories | D-Day’s Most Valuable Player

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!