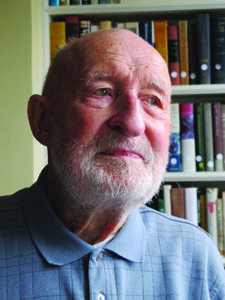

Albert J. Schmidt, 91, lives in Washington, DC. A retired history professor, he still publishes scholarly papers and reviews. Schmidt grew up in Louisville, Kentucky, where he and best friend Wilbert Block delivered the Courier-Journal and the Times. Besides distributing the papers, Schmidt read them closely, especially after war began in 1939. At 17, he volunteered for the U.S. Army Air Forces, figuring he would be drafted after graduating from high school in 1943. In the meantime, he applied to DePauw University. The war interrupted his college education at DePauw with experiences that put young Schmidt face-to-face with history.

How much college did you squeeze in?

I expected to be called up when I turned 18 in August 1943. I decided to go to a summer session at DePauw, which was starting a navy V-12 program. The session turned into a full semester that lasted until October. I still hadn’t been called up, so I finished a second semester, which ended in February 1944. I was about to start a third semester when I got the call.

What was your progress in uniform?

I spent most of 1944 at radio operator school in Scott Field, Illinois. My barracks was alongside runways where the B-29s landed and took off. Then, in 1945, I transferred to MacDill Field, Florida, until I got an overseas assignment. On the day the dignitaries met in San Francisco to formalize the United Nations, April 25, 1945, I shipped out for the South Pacific aboard the SS Lurline. I felt very humbled as I passed under the Golden Gate Bridge.

How was your voyage west?

We sailed unescorted, zigzagging. We learned about V-E Day from the ship’s newspaper. The Lurline took about three weeks to reach Finschhafen, New Guinea, our first stop. We spent several days at Manila, where we were told victory in Europe had nothing to do with our getting back soon. I wandered that war-torn city, hearing artillery in the distance and seeing dead Japanese, but by and large the conflict had gone beyond the area. I was then assigned to Nadzab, New Guinea, by way of Morotai and Biak—places that a few years before had been the scenes of fighting. Finally, I arrived there at a supply and training base, where I was assigned to the Thirteenth Air Force.

What was the mood in Nadzab?

The war clearly was winding down in our favor. In July 1945 we broke camp and our huge flotilla returned to Manila by LST. On the way, I was intrigued to see volcanoes erupt. The Manila Harbor was so congested, we had to wait days to unload. We went to Camp Dow, a staging area, and then headed over to the huge U.S. base at Clark Field. That’s where I was when the A-bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

A big relief.

Yes—and I found Will Block, my boyhood friend, who was assigned to General MacArthur’s headquarters. I knew Will was there from the grapevine. We celebrated our reunion by going to the largest post exchange in the Pacific and devouring delicious hamburgers—like nothing I had tasted for quite a long time. We saw General MacArthur outside his headquarters and when he was out of sight we kicked the tires of his limousine for luck. Will even gave me packets of photos of the Japanese emissaries who had arrived in the Philippines to arrange for the surrender aboard the battleship Missouri. We’re still friends.

What were your duties?

I operated air/sea rescue, but I had lots of free time. I heard that the authorities were going to try two Japanese generals for war crimes: Masaharu Homma, who had commanded Japanese troops in the Bataan Death March, and Tomoyuki Yamashita, who had commanded Imperial troops in the Philippines in early 1945. I knew that Yamashita had won fame by conquering Singapore in 1942. The trials were to take place at the Philippine president’s palace in Manila, 60 miles away. I decided to attend.

How did you manage that?

I had made sergeant, and was the ranking noncommissioned officer in radio communications at Clark. It was easy to catch a ride to Manila in a jeep or transport plane.

Set the scene.

The trials took place in a large hall. The defendants, staff, and prosecutors sat in front. Yamashita seemed very intent, listening to the prosecution make its case. He was emotionless yet very dignified, and in military uniform. Homma dressed in civilian clothes. He, too, was very dignified. I was impressed by both men, considering how high the feeling was against the Japanese. Years later, in Allan Ryan’s book about the trial, Yamashita’s Ghost, I found myself in a photo of the audience. I recognized the back of my head—which at the time still had hair on it.

What was the atmosphere?

Businesslike. For Yamashita, the question was one of command responsibility. After he had assumed command of Japanese forces in Manila later in the war, there were horrible atrocities and destruction. He was charged with failing to exercise command responsibility; in retrospect, I think it questionable whether he was as irresponsible as the charges made out, because historians feel General MacArthur was determined to wreak vengeance on him. At the trial’s conclusion, Yamashita was very polite. He read a statement thanking his defense attorneys. Then he was dishonored—his rank and decorations torn from his uniform—and sentenced to hang, instead of the more honorable death by firing squad—Homma’s fate. The Yamashita proceedings went on a month or so. Homma was tried shortly thereafter, also in a businesslike way. MacArthur seemed to have less interest in Homma than in Yamashita.

You returned home in May 1946. What then?

I reenrolled at DePauw. I thought I would be a big shot but instead I was a lowly sophomore. Two roommates and I lived in a cubbyhole. I majored in history, thinking I would teach high school. I took education courses but concluded this was not my calling. I wanted to be a college professor.

After DePauw, I still had enough GI Bill money to take me through a doctorate program at the University of Pennsylvania. I taught until 1960, then applied for a National Defense Education Act fellowship to go to Indiana

University’s Russian and Eastern European Institute. After that I became dean and vice president at the University of Bridgeport in Connecticut.

I concluded my academic career by attending New York University Law School, which led me into a decade of teaching topics in legal history. One of the courses I taught focused on the trial of Tomoyuki Yamashita.