Editor’s Note: No doubt that Pat Garrett strayed from the truth at times in his 1882 biography of Billy the Kid, but should we discount the generally accepted fact that Garrett killed the Kid on July 14, 1881? The traditional account of the famous shooting has been reported in Wild West and elsewhere many times. The story that follows challenges many of those assumptions, and we leave it to you to decide its merit. Let us know what you think.

During the past 50 years, there has been a growing interest in research that points out the flawed and suspect nature of much of the prevailing history relating to the outlaw Billy the Kid and the Lincoln County War.

Among the principal reasons for the increased critical examination of the Kid and the war are the revelations of a quiet, enigmatic man who died in Hico, Texas, in 1950.

Recommended for you

Although he denied it at first, William Henry Roberts later claimed to be Billy the Kid, the same man allegedly shot down by Sheriff Pat Garrett in Fort Sumner, New Mexico Territory, around midnight on July 14, 1881.

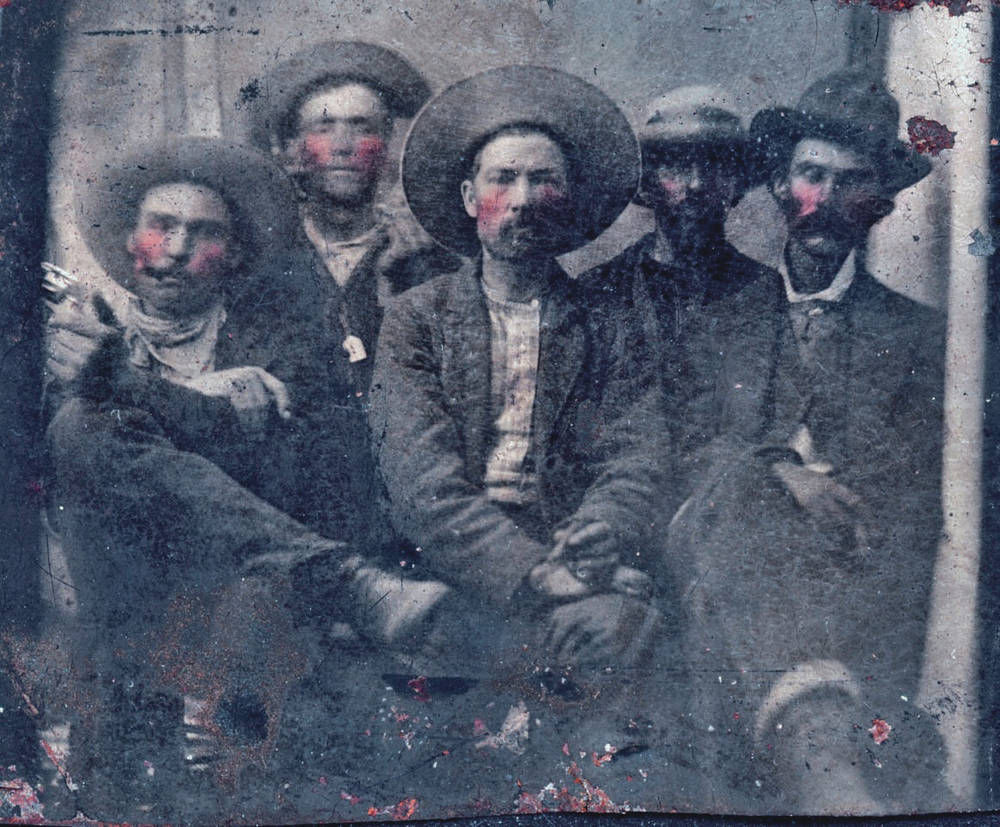

Roberts, who picked up the nickname “Brushy Bill” while riding scout for a stagecoach line in the Black Hills of Idaho, had the look, the size, the eyes and even, according to those who knew the outlaw, the same laugh as Billy the Kid. A Roberts–Billy the Kid photo comparison conducted by the University of Texas at Austin and validated by the FBI showed Roberts and the Kid to be the same person (detailed in the 2005 book Billy the Kid: Beyond the Grave, Taylor Trade Publishing). Just as important, when Roberts was interviewed about his background, it was clear he knew more about the people, places, events and aspects of Billy the Kid during late-1870s and early-1880s New Mexico Territory than the so-called scholars of the day.

Roberts’ revelations caused many to reexamine and reevaluate the existing published history, a great deal of which was derived from Garrett’s book (ghostwritten by Marshall Ashmun “Ash” Upson), The Authentic Life of Billy, the Kid, and parroted by a number of self-styled historians. What was found was, according to writer Frederick Nolan, “a farrago of nonsense” that “has been responsible for every single one of the myths perpetuated about Billy the Kid” and for “many inaccuracies, evasions, and even untruths.” Most serious historians today denounce this book as little more than a collection of misinformation and fabrication. Garrett, it turns out, could not be trusted to tell the truth.

By contrast, Roberts’ credibility grows with each passing investigation into his past and his recorded statements. In addition to the aforementioned photo-comparison study and Roberts’ stunning revelations regarding the history and geography of the time and place, a genealogy found in a Bible among Roberts’ possessions showed family members with the names Bonney, McCarty and Antrim, all known aliases of the outlaw.

Those people who insist on preserving the historical status quo offer various criticisms: Billy the Kid was right-handed while Roberts was left-handed; the Kid spoke fluent Spanish and Roberts did not; Deputies John Poe and Thomas “Kip” McKinney concurred with Pat Garrett that the man shot and killed on July 14, 1881, was Billy the Kid, and Poe’s published narrative agrees with Garrett’s; finally, according to Roberts’ niece, William Henry Roberts was actually Oliver P. Roberts, whose life is documented and shows he could not have been the famous outlaw.

The truth is that Roberts was ambidextrous; Roberts spoke fluent Spanish; at various times in their lives deputies Poe and McKinney both stated Sheriff Garrett did not kill Billy the Kid, and Poe’s narrative contradicts Garrett’s on several major points; William Henry Roberts had no nieces and often used the alias Oliver L. Roberts, never Oliver P. Roberts, who was a cousin and a man often misidentified as William Henry by careless researchers.

Chief among the historical contradictions and confusions are the issues related to the inquests and the burial of the man Garrett claimed was the outlaw Billy the Kid.

Inquests into Billy’s death

According to published history, Postmaster Milnor Rudolph was summoned to Fort Sumner from his residence six miles away early on the morning of July 15, 1881, to conduct an inquest on the death of a man Sheriff Garrett insisted was the Kid. Rudolph found the townspeople excited, confused and hostile. Garrett, Poe and McKinney were barricaded in the bedroom of rancher Pete Maxwell, concerned that they might be attacked by an angry mob sympathetic to the Kid and resentful of the lawmen. Inside that room, Rudolph soon learned, lay the body of a young man Garrett had shot hours earlier.

Rudolph was placed in charge of a coroner’s jury and told to assemble witnesses. He enlisted five men and held a meeting in Maxwell’s bedroom, where the body still lay on the floor. However, in the book later written by Garrett and Upson, the sheriff claimed the body had been carried to a carpenter’s shop shortly after the shooting, where it was allegedly laid out for a wake. It is unlikely that the body was reclaimed from the wake and repositioned on the floor of Maxwell’s room. This was to be the first of several contradictions relating to the inquest of the man Garrett shot and killed.

Rudolph and the five-man jury listened as Garrett and Maxwell recounted the events of a few hours earlier. History records that Rudolph then wrote out a report that was signed by the jurors. Those who could not write made their mark. The inquest concluded that “William Bonney was killed by a shot in the left breast, in the region of the heart, fired from a pistol in the hand of Patrick F. Garrett, and our verdict is that the act of the said Garrett was justifiable homicide, and we are unanimous in the opinion that the gratitude of the whole community is due to the said Garrett for his act and that he deserves to be rewarded.”

For reasons that have never been explained, this coroner’s report was never entered into the official records of San Miguel County. Furthermore, Fort Sumner Justice Alejandro Segura never made an entry regarding this report in his own books. Even more perplexing is the fact that the Rudolph inquest was the second one conducted that day.

Like the shooting, the inquests of the man Garrett killed have remained shrouded in confusion and mystery, and the speed with which they were processed was peculiar and suspicious. “Lawmen of the day,” wrote Frank Richard Prassel in The Great American Outlaw, “normally went to considerable effort to verify the deaths of fugitives for two good reasons: To foreclose a later charge of killing an innocent party and to facilitate the collection of rewards.”

Some believe that the Rudolph report was dictated by Garrett himself and that the sheriff displayed uncommon haste in processing the inquest, as well as in getting the dead man buried. Garrett did not have the body of one of the Southwest’s most wanted badmen placed on display, a common practice of the time. Furthermore, Garrett did not take the time to pose for a photograph with the body, another accepted custom of the day. Garrett was, above all, a politician who aspired to greater office, and a photograph of him alongside the body of the most famous outlaw in the territory would have assured him a lot of votes—unless, of course the dead man was not Billy the Kid.

According to some versions of the incident, Garrett kept the body of the deceased locked in Maxwell’s bedroom throughout the night and allowed only a few to view it. Just as bothersome is the mysterious earlier inquest, one made only minutes after the shooting and well before the arrival of Rudolph. A.P. Anaya, later a member of the state Legislature, once told the editor of New Mexico magazine that he and a friend were members of that first jury and “were called… the night the Kid was killed, and that this jury wrote out a verdict stating simply that the Kid had come to his death at the hands of Pat Garrett, officer.” Some question exists as to whether the members of this jury ever saw the body of the dead man.

Anaya claimed this verdict was suddenly and mysteriously lost shortly after it was completed and that Garrett and Manuel Abreau, Maxwell’s son-in-law, wrote a second one, a “more flowery one for filing.” Different signatures by men who were not part of the first inquest and who may not have actually seen the body appeared on the second report. Strangely, names of the signers were misspelled, leading to the suspicion that the report may have been a forgery arranged by Garrett. To add to the confusion, E.B. Mann, writing in Guns and Gunfighters, states that only three witnesses identified the body and that one of them later claimed it was not Billy the Kid.

The sequence of events involving two separate inquests is unusual and provides for warranted skepticism. Why was an inquest never recorded in the records of San Miguel or Lincoln County? According to historian William A. Keleher in Violence in Lincoln County, the second report was written in Spanish and attached to a cover letter penned by Garrett. Keleher claims that a copy of this document was found during the 1930s in the Office of the Commissioner of Public Lands in the capitol in Santa Fe and then lost. If Keleher is to be believed, it remains curious why such an important document was not properly processed and cared for. To date, Keleher’s claim is dubious and has never been substantiated.

Garrett said he filed the second report with the district attorney of the First Judicial District in Las Vegas, the San Miguel County seat. Outlaw hobbyist Donald R. Lavash maintains that “the coroner’s report is properly considered a death certificate and is on file at the [New Mexico State Records Center and Archives] in Santa Fe.” Why Lavash would make such a statement is unclear since no such document has ever been located there and no one has ever been able to find it anywhere. According to Alicia Romero, New Mexico secretary of state in 1949, there “is no record in this office of any coroner’s verdict in the purported death of William H. Bonny [sic].”

In August 1951, Fourth Judicial District Attorney Jose E. Armijo wrote that a coroner’s report “is not now, and never has been, among the records in this office.” That same month, Lincoln County War historian Maurice G. Fulton claimed he had in his possession a “photostatic copy” of an inquest, though he never said whether it was the first or the second. Fulton also claimed he discovered the document “while searching the file dealing with the reward for the killing of Billy the Kid…among the records of the office of the Secretary of the Territory of New Mexico.” Fulton’s document was immediately challenged, and his story has never been validated. In other words, the killing of the outlaw Billy the Kid was never officially recorded in the state of New Mexico, and the fact remains that there exists no legal proof of the death of Billy the Kid.

Garrett experienced difficulty in collecting the $500 reward offered for the apprehension of the Kid. He petitioned for the money on July 20, 1881, and was denied by acting Gov. W.G. Ritch, who raised questions relative to whether or not Garrett had really killed the outlaw. Garrett apologists insist that his request was denied because his application was not in proper legal form. Others suggest it was denied because the purported death certificate was never found.

As a result of the difficulty related to collecting the reward, a third coroner’s report was initiated. This document, like the second, was written by Manuel Abreau, and, according to author Jon Tuska in Billy the Kid: A Handbook, it bears signatures of men “who had not been present at the original hearing and it contains obviously slanted statements which indicate for what use it was intended.”

If Garrett had killed Billy the Kid in Maxwell’s bedroom, none of these ploys would have been necessary. To cover the mistake of shooting the wrong man, Garrett hurried along not just one but two coroner’s reports, refused to place the body on display, refused to have his photograph made with the corpse, had the body buried posthaste and then almost a week later initiated a third coroner’s report.

Tuska states that it is “possible that the original document mentioned that the Kid was unarmed and was therefore suppressed.” Tuska also raises the question of whether the coroner’s jury, made up of men largely sympathetic to the Kid, would have concluded by recommending the reward not be paid to Garrett. Perhaps that is the reason why the original became “lost” within minutes after being written. Since Garrett was the official in charge, he bears complete responsibility for losing the document and orchestrating the second report, the one that was, in fact, more favorable to him.

On February 18, 1882, Garrett purchased approximately $500 worth of drinks for members of the New Mexico Territorial Legislature, a group heavily loaded with his political cronies. A short time later, these same men voted to pass an act providing the reward money for “the arrest of Billy the Kid.” Apparently none of the legislators knew, or cared, that Garrett had never arrested anyone or that the identity of the man he shot was already in dispute. The act, written by the legislators, credits Garrett with killing Billy the Kid “on or about the month of August, 1881.” They couldn’t even get the date correct.

Given the facts related to the three inquests following the shooting of the man Garrett claimed was the famous outlaw, coupled with the sheriff’s documented lack of veracity, it is not possible to conclude without a doubt that the man he shot was the outlaw Billy the Kid.

Was it billy who was buried?

Like the shooting and the inquests, the burial of Sheriff Garrett’s victim has not escaped criticism and controversy. Apparently, Garrett could not get the body into the ground fast enough.

According to most accounts, the dead man was dressed and prepared for burial immediately after the second inquest. On the afternoon of July 15, 1881, the body was placed in a hastily constructed wooden casket and interred at the Fort Sumner military cemetery next to the graves of Tom O’Folliard and Charlie Bowdre, friends of Billy the Kid. Though difficult to verify, there is a strong possibility that only two people other than Garrett, Poe and McKinney ever saw the body of the dead man.

In his biography Pat Garrett: The Story of a Western Lawman, Leon Metz brings up the possibility that passing off any body as that of Billy the Kid could easily have been done “since neither…Poe nor…McKinney recognized the Kid, and both would be inclined to accept almost any body that Garrett claimed was Billy’s.” Garrett could then petition for the reward, says Metz, as well as the honor and prestige that went with killing the Southwest’s most famous outlaw.

On July 28, an obituary titled “Exit the Kid” appeared in the Grant County Herald, a Silver City newspaper. Editor S.M. Ashenfelter wrote, “Since his escape from the Lincoln County jail, [the Kid] has allowed his beard to grow and stained his skin brown to look like a Mexican.” Ashenfelter most likely wasn’t in Fort Sumner, and the source of his information is unknown.

A mere 6 1⁄2 months before the shooting in Fort Sumner, J.H. Koogler, editor of the Las Vegas Gazette, interviewed the Kid while he was in that town waiting to be moved to Mesilla for his trial. Koogler described the outlaw this way: “There was nothing very mannish about him in appearance, for he looked and acted a mere boy. He is about five feet eight or nine inches tall, slightly built and lithe, weighing about 140; a frank open countenance, looking like a school boy, with the traditional silky fuzz on his upper lip; clear blue eyes, with a roguish snap about them; light hair and complexion.”

Ashenfelter’s description of the dead man having a beard and brown skin does not fit Billy the Kid. In the book Alias Billy the Kid, C.L. Sonnichsen and William Morrison relate some information from a man named Arthur Hyde. During a 1914 interview, Hyde stated that it was not the Kid who was shot by Garrett, but a young Mexican who had been set up by Garrett. According to Sonnichsen, William Henry Roberts explained that the man who was killed by Garrett was a friend of his named Billy Barlow, an elusive and occasional resident of Lincoln and San Miguel counties. Barlow, who was half Mexican, bore a strong resemblance to Billy the Kid, save for his beard and dark skin.

Dr. J.M. Tanner, in the book Growth at Adolescence, discusses sexual maturity ratings (SMRs), which are developmental stages not necessarily related to chronological age. SMRs 1 and 2 are associated with early adolescence in males 10 to 15 years of age. During SMR 2 in males, facial hair may appear, and it is often of a fine and silky nature. Middle adolescence (SMRs 3 and 4) typically begins between the years 12 and 15. Late adolescence (SMR 5) is generally reached between the 14th and 16th years, although it may not appear until much later, sometimes in the early 20s. During this phase, secondary sex characteristics develop. In males, facial hair spreads to the chin and grows darker. Tanner points out that the length of time between SMR 2, associated with the silky fuzz observed by Koogler, and SMR 5, associated with the dark beard described by Ashenfelter, can take three years or more.

If Billy the Kid, at age 20 to 21, was still sporting “silky fuzz on his upper lip,” it indicates he was experiencing delayed sexual maturity. It is improbable to impossible, given the chronology of the SMR sequences, that the Kid could have gone from silky fuzz to beard in only 6 1⁄2 months. Based on the unchallenged descriptions provided by Ashenfelter and Koogler, the body in the casket could not have been that of Billy the Kid. The notion that the skin of the dead man was stained, as Ashenfelter suggests, is absurd. The likelihood that greasepaint, or any other kind of skin-tinting application, was available in Fort Sumner in 1881 is far-fetched. Furthermore, it is likely that any stain that might have been applied to the victim would have been removed during the preparation of the body for burial.

In a March 1980 article that appeared in Frontier Times magazine, writer Ben Kemp shares some pertinent information related to him by his uncle John Graham, a Fort Sumner resident who knew Billy the Kid. On the morning after the shooting, Graham and a Mexican were sent to the cemetery to dig a grave for Garrett’s victim. Graham stated that when the wagon carrying the casket arrived, it was accompanied by an armed guard “with strict orders to see that no one opened it to see what was inside.” The word used was what, not who.

According to Kemp, Graham agreed with Deputy Poe that the body of the dead man was removed from Maxwell’s residence a short time after the shooting and not in the morning, as stated by others. Kemp quotes Graham, however, as saying that an acquaintance told him that the man killed by Garrett was one of Maxwell’s hired hands.

The late Verna Reed, a Carlsbad, N.M., resident, said that her great-grandfather Joseph Wood helped Graham with the burial. All his life, Wood insisted that the casket contained a whole side of beef, the one that hung near Maxwell’s room on the night of the shooting. If there was a body, it was more likely that of cowboy Billy Barlow, who had the same size and general appearance as the Kid but was slightly younger.

The original wooden marker placed at the head of the grave of the man killed by Garrett was used by drunks for target practice and reduced to splinters. According to a 1938 interview with Carolatta Baca published in the book They Knew Billy the Kid, very few people in Fort Sumner knew the location of the original grave site. Twenty-two of the bodies in the cemetery were those of soldiers, many of them lacking identification. In 1906, the soldiers were disinterred and reburied in the Santa Fe National Cemetery. Some claim the bones of the man shot by Garrett were among them, but evidence is lacking.

On a number of occasions during the past 125 years, the nearby Pecos River has flooded, inflicting severe damage to the unmaintained cemetery located on the adjacent flood plain. High-velocity floodwaters carried away headstones and markers along with entire caskets and their contents. By the 1930s, very little of the original cemetery was recognizable.

In 1937, the four pallbearers of the man shot by Garrett were still alive and living in Fort Sumner. Vicente Otero, Yginio Salazar, Jesus Silva and Charlie Foor were brought to the old cemetery and asked to agree on the original location of the grave. They were unable to do so, each man selecting a different site. Finally, they agreed to compromise by placing a marker at the approximate center of the four different choices. According to the late George E. Kaiser of Artesia, N.M., there was another major flood in 1943 that washed away this newer marker as well as the few remaining graves.

The current location of the purported graves of Billy the Kid and his close companions Tom O’Folliard and Charlie Bowdre is an important tourist attraction of Fort Sumner. The fact remains, however, that there is a distinct possibility that neither Billy nor anyone else is buried beneath the marker. When researchers Steve Sederwall and Tom Sullivan requested permission to open the grave to conduct an analysis on the remains in order to settle the dispute once and for all, the city denied their request.

Given a logical and in-depth analysis of the events surrounding the inquests and the burial of the man shot by Garrett, given Garrett’s demonstrable lack of credibility and given Deputy John Poe’s subsequent published contradictions of Garrett’s account, there is little evidence or rationale to conclude that the lawman shot and killed the outlaw Billy the Kid.

W.C. Jameson of Woodland Park, Colo., is the author of 45 books, including Billy the Kid: Beyond the Grave (Taylor Trade Publications), which is recommended for further reading.

Originally published in the February 2007 issue of Wild West.