Gilbert Elliott was only 19 when he oversaw construction of the fearsome warship

Like the mists that rose at dawn, the rumors began drifting down the Roanoke River in the summer of 1863, alarming the Yankees occupying the dingy river port of Plymouth, N.C. Somewhere upstream, hidden by the juniper and cypress bogs that surrounded this valuable Union supply depot at the entrance to Albemarle Sound, the Confederates were apparently building something dangerous—something that could challenge the Union flotilla anchored in the Roanoke as well as threaten the 3,000 bluecoats defending Plymouth. What the rumors didn’t specify was that a 19-year-old engineer-inventor, the unknown Gilbert Elliott, was the one constructing this infernal machine—to be christened CSS Albemarle—in a makeshift shipyard in the middle of a fallow cornfield on Peter Smith’s Edwards Ferry plantation.

ven though the sea was, to some degree, in Elliott’s blood—his maternal grandfather, Charles Grice, owned a shipyard in Elizabeth City, N.C.—the youngster had been leaning toward a law career. But once the war began, he enlisted in the 17th North Carolina Infantry and served in his native state until captured at Cape Hatteras Inlet in December 1861. Exchanged shortly thereafter, he was assigned to the James River’s Drewry’s Bluff battery near Richmond.

To pass time, Elliott began sketching designs for warships, and, on a whim, sent the sketches to Navy Secretary Stephen Mallory, who was looking for help in breaking the Union’s suffocating naval blockade of Southern waters. Mallory had three construction contracts to let, and Elliott was among the recipients.

Convinced the shipyard had to be set up on dry land, Elliott selected Smith’s plantation. “The river rises and falls,” he wrote, “and it was necessary to locate the yard on ground sufficiently free from overflow, to admit the uninterrupted work for at least twelve months.”

John L. Porter, the man responsible for converting USS Merrimac into CSS Virginia in 1861, prepared the vessel’s plans and specifications and joined Elliott at Edwards Ferry to supervise construction. They were soon joined by Captain James Wallace Cooke, the ironclad’s designated commander.

Everything at the cornfield shipyard was makeshift, but Smith became a willing partner in the enterprise and had three portable lumber mills constructed to cut the sturdy yellow pine timber for the vessel’s hull. Construction—by a team of white carpenters and slaves from nearby plantations—continued day and night in spite of the stifling heat and humidity that were staples of the North Carolina summer.

For many months, there was fear the 376-ton creation would never launch, since the iron needed for its plating was so scarce in the South. Elliott finally obtained 700 tons of iron from abandoned railroad tracks in February 1864, but because of the Confederacy’s limited industrial capacity, it first had to be smelted at Richmond’s Tredegar Iron Works and didn’t reach Elliott until March 7.

The project was also beset by administrative issues. Questions over contract terms cropped up, especially after William F. Lynch, the state’s ranking naval officer, got involved. In October 1863, he assumed overall supervision of construction and, fearing Edwards Ferry was too vulnerable to Union cavalry raids, ordered the unfinished vessel towed upstream to Halifax. “For many reasons it was thought judicious to remove the boat to…Halifax,” Elliott later wrote, “and there the work of completion, putting in her machinery, armament, etc., was done….”

The hull was bent while dragging it from the cornfield, situated on a bluff, to the river bank below, “but to our great gratification did not…spring a leak.” Once the hull was straightened, it was hauled 22 miles up the turgid Roanoke River to await its cloak of armor.

The finished Albemarle was 152 feet long by 45 feet wide. “The depth from gun-deck to keel was 9 feet,” Elliott noted, “and when launched she drew 6½ feet of water but after being ironed and completed her draught was about 8 feet.”

Each of the ram’s two iron plates was seven inches wide and two inches thick, and its 18-foot oak prow was covered with two inches of iron plating. The vessel was armed with two 6.4-inch rifled Brooke guns mounted on pivot carriages, each gun able to work three gunports. Propelled by two 200-hp steam engines, its top speed would be four knots.

In the spring of 1864, General Robert E. Lee began looking for ways to regain the war’s initiative in the Confederate heartland, as well as reduce building pressure by the Union Army of the Potomac against Richmond, and he detailed North Carolina native Brig. Gen. Robert F. Hoke to launch an offensive against Plymouth. The Union garrison there was well-protected by forts, extensive trench lines, and a formidable flotilla. Clearly, Hoke could use Albemarle’s aid.

Meeting with Cooke, however, Hoke found a cautious captain, worried that the ram was still being fitted to the prow, the ship lacked capable crew members, and it had yet to have its “shakedown” cruise. Adamant, Hoke promised mechanics and sailors, inducing Cooke to agree to join his planned attack by April 17, 1864.

With a force of roughly 10,000 men, Hoke showed up at Plymouth on time—Albemarle did not. A series of infantry attacks on the 18th had limited success, but Union naval gunfire from the river inflicted heavy losses in the Rebel ranks. The battle continued well into the night before Hoke called a halt.

Albemarle reached Plymouth the following day, after being delayed by both mechanical problems and sunken Union boat hulls. During a longboat reconnaissance conducted on the 18th, with the help of volunteers, Elliott personally took measurements and found that the ironclad could make it over the hulls safely. On its approach to Plymouth, Albemarle’s iron plating easily withstood the artillery fire from the Union forts. “[T]o those on board,” Elliott wrote, “the noise made by the shot and shell as they struck the boat sounded no louder than pebbles thrown against an empty barrel.”

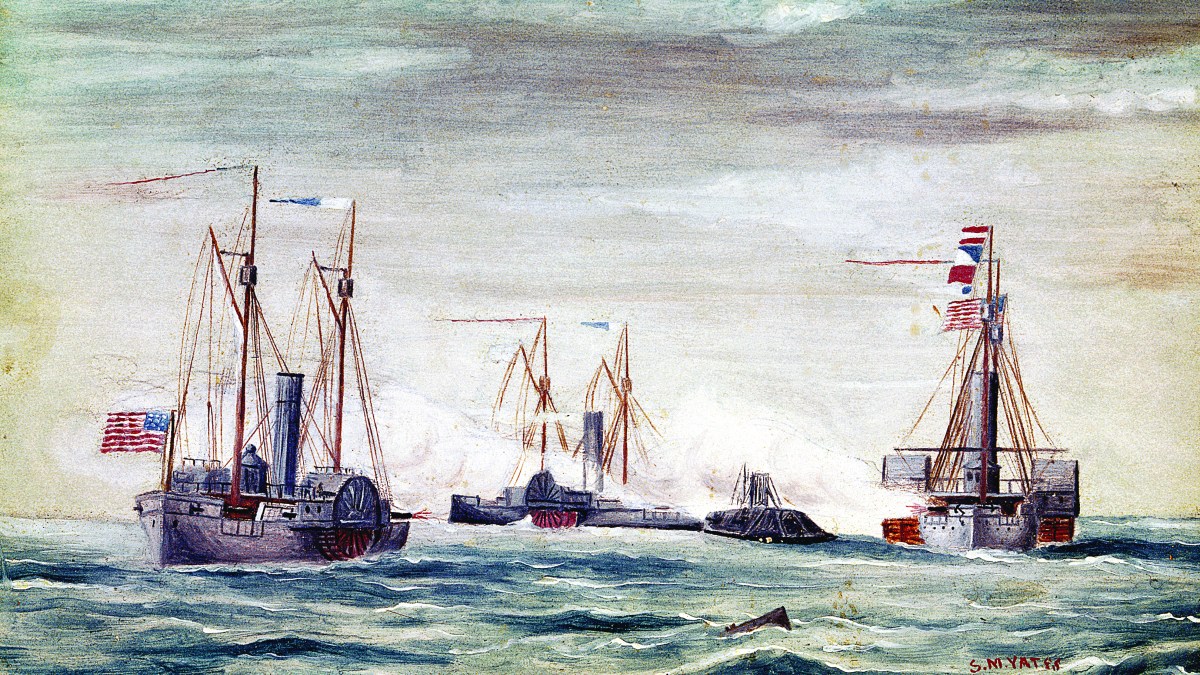

As Albemarle came abreast of Plymouth, USS Miami and USS Southfield were spotted steaming up from the sound. In an effort to trap the Confederate ram between them, the two ships were linked by an iron chain. Recalled Elliott: “Captain Cooke ran the ram close to the southern shore, and then, suddenly turning toward the middle of the stream, and going with the current…dashed the prow of the Albemarle into the side of the Southfield, making an opening large enough to carry her to the bottom….”

Cooke turned his attention to Miami, whose point-blank fire proved ineffectual against Albemarle’s armor. After an attempt to board the ironclad was beaten back, Miami fled downriver. But when dawn broke over the river the next day, there was no sign of Hoke. Elliott and a team of volunteers soon found the Confederate army bivouacked along a creek near the river’s mouth, about 12 miles away, and, with the general, he devised a battle plan in which Albemarle would shell the Union defenses while Hoke launched an infantry attack. By 10 a.m., the attack was over: Plymouth was in Confederate hands.

The fearsome ram would enjoy one more moment of glory. On the afternoon of May 5, 1864, Cooke’s vessel sortied into Albemarle Sound and engaged the entire Union flotilla. All attempts to sink Albemarle failed, and at nightfall both sides retired.

he ram’s mere presence kept it a threat throughout the summer and fall—until October 28, 1864, when Union Lieutenant William Cushing led a daring early morning raid that sank Albemarle in eight feet of water with a spar torpedo. Three days later, Union forces recaptured Plymouth.

Elliott didn’t witness his prize creation’s demise, as he was back at Edwards Ferry constructing another ironclad (not to be completed before the war ended). In 1867, the U.S. Navy refloated Albemarle and towed it to the Norfolk (Va.) Navy Yard. When sold for scrap, Albemarle’s iron fetched a mere $2,500.

Gordon Berg writes from Gaithersburg, Md.

This column appeared in the January 2020 issue of America’s Civil War.