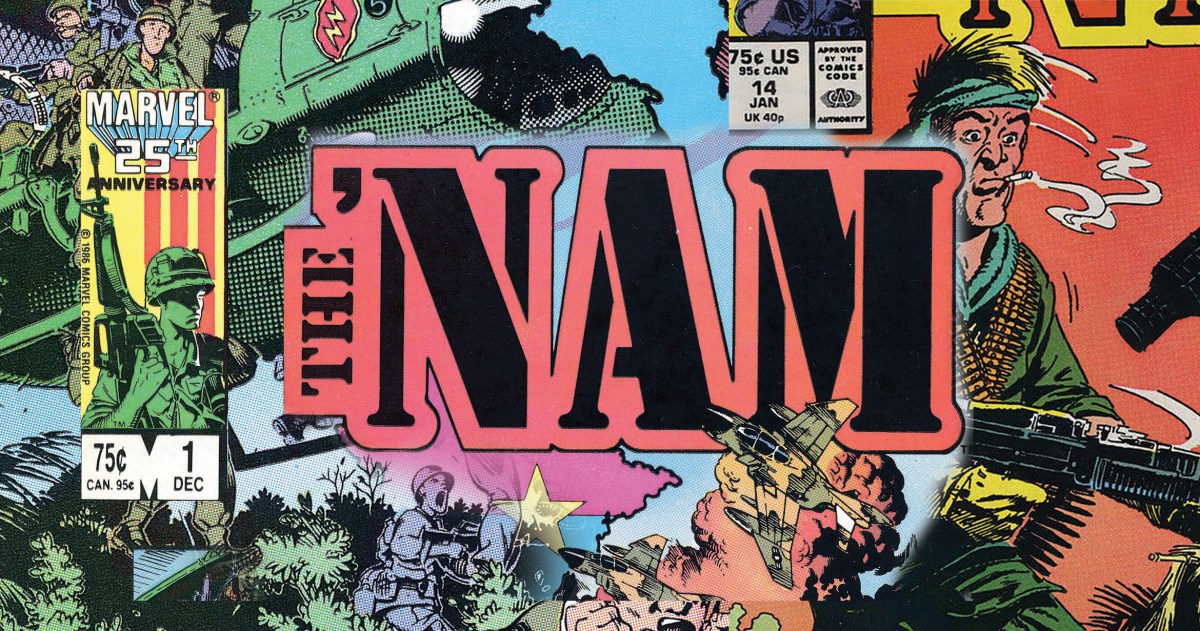

Popular culture interest in the Vietnam War reached a peak in the 1980s, which saw a string of war movies like “Platoon,” “Full Metal Jacket,” “Hamburger Hill,” “Off Limits” and others along with TV series such as “Tour of Duty” and “China Beach.” Some shows, such as “Magnum P.I.” and “The A-Team,” although not set during the war, featured Vietnam veterans as protagonists. Comic books were no exception to the trend. Marvel Comics introduced the highly regarded The ’Nam mid-decade as well as Semper Fi, which featured several Vietnam War stories. Other comics of the era included In-Country NAM and Vietnam Journal.

In 1982, Larry Hama, an Army veteran of the Vietnam War, volunteered to write stories for Marvel’s comic book G.I. Joe: A Real American Hero. Hama’s task was to create background for all characters in that comic, and he made several heroes Vietnam vets. One of the most popular characters, Snake Eyes, had gone on long-range reconnaissance patrols in Vietnam and some of the stories go back to his time there.

A few years later, Hama collaborated with writer Doug Murray, a wounded noncommissioned officer who served two tours, to create a Vietnam war story, “Fifth to the First” for the October 1985 issue of Marvel’s Savage Tales. The story was well-liked, and Hama suggested Murray submit a proposal to Marvel for a war comic set in Vietnam. To Murray’s amazement, Marvel accepted. Murray, editor Hama and Editor-in-Chief Jim Shooter developed Marvel’s The ’Nam in 1986 as a highly realistic war comic written from the perspective of the average infantry “grunt.” The ’Nam’s creators didn’t want a comic built around superheroes or indestructible Rambo-type characters.

The ’Nam team decided to focus the stories on actions at the squad and platoon level during the main combat years, 1966-73, and present them in chronological order for a planned 96 issues, with each issue corresponding to one month in Vietnam. Characters would return to the States when their one-year tour was complete, and new ones would be rotated in to take their place. Murray wanted to attract and educate younger readers about the war, so he got the industry’s self-imposed Comics Code seal of approval, which gave distributors the go-ahead to send the books to mainstream sellers and let advertisers know they could run ads aimed at minors. But it also meant no sex, drugs and profanity.

In the December 1986 premiere issue of The ’Nam, readers met Pfc. Ed Marks, a clean-cut young man with a fear of heights who boards a plane in January 1966 at McChord Air Force Base in Washington, bound for South Vietnam. He was assigned to the 4th Battalion (Mechanized), 23rd Infantry Regiment, 25th Infantry “Tropic Lightning” Division.

On his first day in-country, Marks goes to Cu Chi base camp, the division’s home, about 25 miles northwest of Saigon, where he meets a corrupt first sergeant expecting a bribe. Marks introduces himself to the men of his squad, who in turn, introduce him to the “you can tell its Mattel” rifle, a common reference to the M16 because it was lightweight and made of plastic components, like toy guns. Marks had trained on the older wood-stocked M14.

The next day Marks and his squad embark on a search and destroy mission that includes a firefight in a village. Back at Cu Chi that evening, the 4th Battalion men are watching Major Dundee on an outdoor screen when Viet Cong rockets slam into the base. Marks jumps to his feet, but no one else moves. His comrades assure him that the enemy won’t rocket their part of the base because the VC want to watch the movie too.

During his tour, Marks survives a terrorist attack at a Saigon hotel and combat actions in the bush. He accompanies a “tunnel rat,” a soldier who went down into tunnels hunting for Viet Cong hidden there. On one patrol, Marks and his squad are doused with the poisonous herbicide Agent Orange, used to clear vegetation that could provide cover or food for the enemy.

Disgusted by what he considers the U.S. media’s biased portrayal of the Vietnam War, Marks decides to study journalism and become a war correspondent. In issue No. 70, spring 1972 in the chronology, Marks returns to Vietnam as a journalist and his editor sends him to a firebase to cover the story of a Special Forces A-Team.

The ’Nam dealt with many topics and issues including fragging (killing officers with grenades that explode into fragments), prisoners of war, river patrol boats, downed pilots and rescue missions, war protesters and racial tensions, including fistfights caused by misunderstandings.

Although the main characters in the featured squad are fictional, they see real historical figures and events. Bob Hope and his ubiquitous golf club visit Cu Chi with a USO tour group on Christmas Day 1968. Ann-Margaret joins him on stage just as she did in real life. Actress Chris Noel, who risked her life visiting landing zones in forward areas, made the cover of issue No. 23.

Issue No. 24 deals with communist attacks throughout South Vietnam during the 1968 Tet Offensive. The cover shows photojournalist Eddie Adams snapping one of the most famous photographs of the war: Maj. Gen. Nguyen Ngoc Loan executing a communist prisoner. The fictional men of the 4th Battalion, 23rd Infantry, are ordered to Saigon where they help defend the U.S. Embassy compound. Afterward, they participate in the fighting at a Saigon radio station and later witness Adams taking his Pulitzer Prize-winning photo. Squad leader “Ice” gives his cynical response to the photo: “Front page of every newspaper in the States!”

Continuing the story of the Tet Offensive, the next issue sees two fictional heroes visiting Marine friends at Khe Sanh in northern South Vietnam when the base comes under heavy attack. The two fictional characters assist the Marines as they retake Hue in one of the largest battles of the war. House-to-house fighting eventually puts the Marines in control of southern Hue and they discover a mass grave of civilians murdered by the communists.

Issue No. 29, which covers a busy June 1968, is chock-full of real people and events. It opens with the Paris peace talks while ensuing panels depict the heated exchange between diplomats Xuan Thuy of North Vietnam and Averell Harriman of the United States. At the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, Sirhan Sirhan fatally wounds presidential hopeful Robert F. Kennedy. On another page, Gen. Creighton Abrams replaces Gen. William Westmoreland as head of Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, in charge of all U.S. combat forces in South Vietnam. In a Boston courtroom, Dr. Benjamin Spock is found guilty of encouraging men to violate draft laws.

In another issue, as Marks watches TV in the battalion’s club facility, CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite is reporting on the war. Marks observes that Cronkite exaggerates communist successes at Da Nang: “You’d think the whole corps was wiped out.”

The issue covering October 1968 pictures President Lyndon B. Johnson announcing a halt to all B-52 bombing strikes against North Vietnam. The 75th issue looks at the My Lai Massacre in a four-story, 48 page-special edition highlighting the March 16, 1968, atrocity involving 2nd Lt. William Calley and elements of two rifle companies who killed Vietnamese civilians.

Readers were unhappy when the storyline veered too far from the fictional heroes and were incensed when The ’Nam ventured into the greater Marvel universe in issue No. 41. Captain America, Ironman and Thor appear on the cover—but to be fair, the superheroes exist only in the imaginations of the grunts reading about them. Ice and Martini, another recurring character, daydream about what would happen if the superheroes were in Nam taking on the “commie dupes.” In their dream world, the superheroes snatch Ho Chi Minh, fly him to Paris and force him to sign the peace treaty.

The ’Nam, noted for its historical accuracy and good writing, also enjoys a well-deserved reputation for highly detailed artwork. Several artists worked on various phases of a single issue. The penciler drew each panel. The inker went over the drawing with ink and maybe added more highlighting. A colorist then applied the colors. Finally, the letterist inserted the dialogue, thought balloons and sound effects.

Artist Michael Golden penciled 12 of the first 13 issues. Although the characters appeared slightly cartoonish at first, Golden set the standard for realistic detailing of military uniforms and equipment. Other artists worked on The ’Nam over the years, but Wayne Vansant, who served in the Navy during the war, penciled the lion’s share of the comic, drawing for 58 issues. Uninterested in superheroes, Vansant built his career on military history subjects including the Battle of Gettysburg and the Red Army in World War II.

Vansant grounded his illustrations in extensive research, setting his work apart from the lack of realism he saw in older comics. For example, a World War II Sherman tank that appeared in Marvel’s Combat Kelley and the Deadly Dozen might resemble a Sherman, but aspects of it are completely wrong. DC Comics’ Our Army at War, later titled Sgt. Rock, fared better with Shermans, but the detailing isn’t on par with the tanks in The ’Nam.

Many of the comic’s illustrations have details the casual reader might miss, but veterans appreciated. When the series begins, the men in the 4th Battalion, 23rd Infantry, wear the bright red “electric strawberry” patch of the 25th Infantry Division. As the war progresses, the bright colors of their shoulder patches and rank insignia are replaced with muted colors. Vansant drew the famous UH-1 Iroquois “Huey” helicopter so finely that in many panels we can see the pedals and pilots’ feet through the plexiglass nose.

In another example, a soldier mails a rifle piece-by-piece to his wife in the States. She is seen holding up a metal part, which people familiar with the weapon would instantly recognize as the bolt assembly. One character, Spc. Daniels, the squad’s radio man, carries a realistically sketched PRC-25 backpack radio, with dials, knobs, switch and retaining straps visible. In some panels the cloth bag that holds the handset and spare antennas is visible.

Civilian products are also realistically portrayed. Ice carries a perfectly rendered pack of Marlboro cigarettes under his helmet camouflage band.

Vansant liked to model characters’ faces from real people. “I’ve killed off my brother-in-law lots of times,” he jovially claimed in Marvel Age, an in-house publication where contributors discussed their projects.

The ’Nam was much more than a kids’ comic book with interesting stories. Most issues included a letters to the editor section, “Incoming,” a place where veterans and civilians still hurting from the war could write about friends and family they had lost or how the war had affected them personally. The comic also mentioned veterans organizations and their reunions.

Readers were not shy about pointing out mistakes, which Murray quickly corrected. But some comments put him in a fighting mood. One reader compared American GIs in Vietnam to Nazi death camp guards at Auschwitz and concluded that Vietnam vets didn’t deserve a “ticker tape parade.” In an angry response, Murray said there was no excuse for the way returning vets were treated and considered the comparison of American servicemen to death camp guards as beneath contempt.

Issues usually included “’Nam Notes,” a glossary of GI lingo and Vietnamese phrases, such as “Sky Pilot” (military chaplain), “Charlie” (Viet Cong, the enemy), “White Mice” (South Vietnamese military police), “Didi Mow” (get out quick) and “Titi” (a little bit). Murray listed the number of officers, enlisted men and weapons in a typical rifle company. He also provided the organizational structure from squad to brigade level.

In 1987, Marvel named a new top editor for The ’Nam. Tom De Falco took over as editor-in-chief in issue No. 10 (September 1987). The following year Don Daley became the new series editor, beginning with No. 21 (August 1988). The new editors wanted to make changes such as dropping the chronological order, branching out beyond the single squad and inserting Marvel’s popular Punisher character, a Vietnam veteran who served in the Marines. Those changes did not take place right away, but eventually caused Murray to leave. His last issue was No. 51 (December 1992).

Several writers subsequently joined the team including Roger Salick, who wrote a two-part Punisher tale giving the backstory of Frank Castle, aka the Punisher. Of all the Marvel characters, the Punisher seemed a logical choice for The ’Nam. The prolific Chuck Dixon came onboard for 18 issues and penned a three-part Punisher story in addition to a well-received five-part saga about the war’s mental toll on a Marine named Joe Hallen. Dixon’s writing typically carried a darker tone than Murray’s did, and he often focused on snipers and special operators. Most of his stories involved Marines.

The series finished with Vietnam veteran Don Lomax as the writer for 18 issues. Lomax had written and penciled another comic about the war, Vietnam Journal, published by Apple Comics. Impressed with Lomax’s work, Marvel editor Daley approached him in 1992 to write for The ’Nam.

Lomax, a draftee, served with the 98th Light Equipment Maintenance Company as a wheel and track vehicle mechanic from fall 1966 to fall 1967. He went to mechanic school at Aberdeen Proving Grounds in Maryland and finished second in his class.

“I graduated not knowing a spark plug from a CD850 tank transmission, but it didn’t matter,” Lomax said in an interview for this article. “I ended up in a chemical platoon among others servicing flamethrowers and patching fuel bladders in addition to convoying supplies up the An Khe Pass to Pleiku for the 1st Air Cav,” in an area of South Vietnam’s Central Highlands.

He also repaired typewriters, drove trucks, burned human waste and butted heads with his lieutenant. Lomax was a specialist 4 “with an attitude,” he said. “Being a draftee, my lieutenant didn’t expect me to toe the Army line. He often would threaten to bust my ass, and I would rip off my Spc. 4 patches and hand them to him. He would just shake his head and walk away. By the time I left Vietnam I didn’t have a patch or rank insignia on a single uniform.”

A fan of war comics, Lomax hoped to write one with more realism than those he read in his youth. “Being a truck driver, delivering supplies to a few sticky places I got the opportunity to listen to a lot of stories,” he said. Some of those stories came from men in special operations units “who told about the more freaky individuals they had run into out in the bush. These all became fodder for my Vietnam Journal and later The ’Nam for Marvel.”

Lomax brought back Marks, in issue No. 70 (July 1992), as a war correspondent with a journalism degree from Columbia University. Lomax also included “Stateside” shorts to tell the stories of several popular characters. Although the strict chronological scheme had been dropped, several flashbacks expanded on the 1968 Tet Offensive and the Battle of Hue.

Issue No. 76 features a touching story called “The Paymaster.” A lieutenant risks his life to deliver the payroll to troops at the front. The officer is totally dedicated to his mission, and the forward troops regard him as one of their own: a combat vet. When his chopper lurches unexpectedly, the lieutenant loses the payroll money, which he is responsible for. His new friends sign papers stating that they got paid, even though they hadn’t.

Lomax based that story on a friend. “It was a dangerous job, choppering in to make sure the troops got paid,” Lomax said. “He won a Bronze Star for valor. He took his job seriously, though at many of the forward support bases there was no place to spend it anyway.”

The ’Nam never made it to the proposed No. 96. Marvel executives axed the project in 1993, one year early, making No. 84 (September 1993) the final issue. Sales were down, and management wanted to focus on superhero comics.

The final story is told from the communist perspective. A 5-year-old girl sends a letter to her father, a North Vietnamese soldier who has gone south to fight the Americans. Through a series of strange events the letter changes hands many times and ends up with Marks, who is holding it in the last page of the last issue. The letter contains only a stick figure drawing of the girl’s family members beside their house and water buffalo.

When the series ended, Lomax was a freelance writer not under contract to Marvel. “One day Tim Tuohy [one of The ’Nam editors at the time] called and said No. 84 would be the last,” Lomax remembered. “Sayonara old stick. That was pretty much it for me at Marvel.”

One of the best war comics ever made did not have global conflicts like World War I or World War II as its canvas. It focused on ordinary soldiers in the ’Nam—and it was to a large extent created by Vietnam veterans themselves.

Born and raised in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley and surrounded by Civil War battlefields, Rob Hodges Jr. developed a passion for military history. He also writes literary fiction, science fiction and poetry. His books can be found on Amazon.

This article appeared in the June 2021 issue of Vietnam magazine.