Colin Powell’s journey “from a working-class immigrant neighborhood in the South Bronx to the highest echelons of military, political, and diplomatic power was truly remarkable,” writes Jeffrey J. Matthews in Colin Powell: Imperfect Patriot. He says a crucial component of Powell’s rise—ultimately to chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and secretary of state—was his development as an “exemplary subordinate,” an extremely competent, hardworking, loyal assistant who in turn became an effective, inspirational leader. At times, however, superior “followership” led to failings in independent critical reasoning and errors in judgment, including in Vietnam, contends Matthews, who informed Powell “there would be sections of the book he would not like. To his credit, he encouraged me to ‘write what I think is right.’” Powell’s Army career began as an ROTC graduate in 1958. His first assignments were in West Germany and at Fort Devens, Massachusetts. After promotion to captain in 1962, Powell received orders for Vietnam.

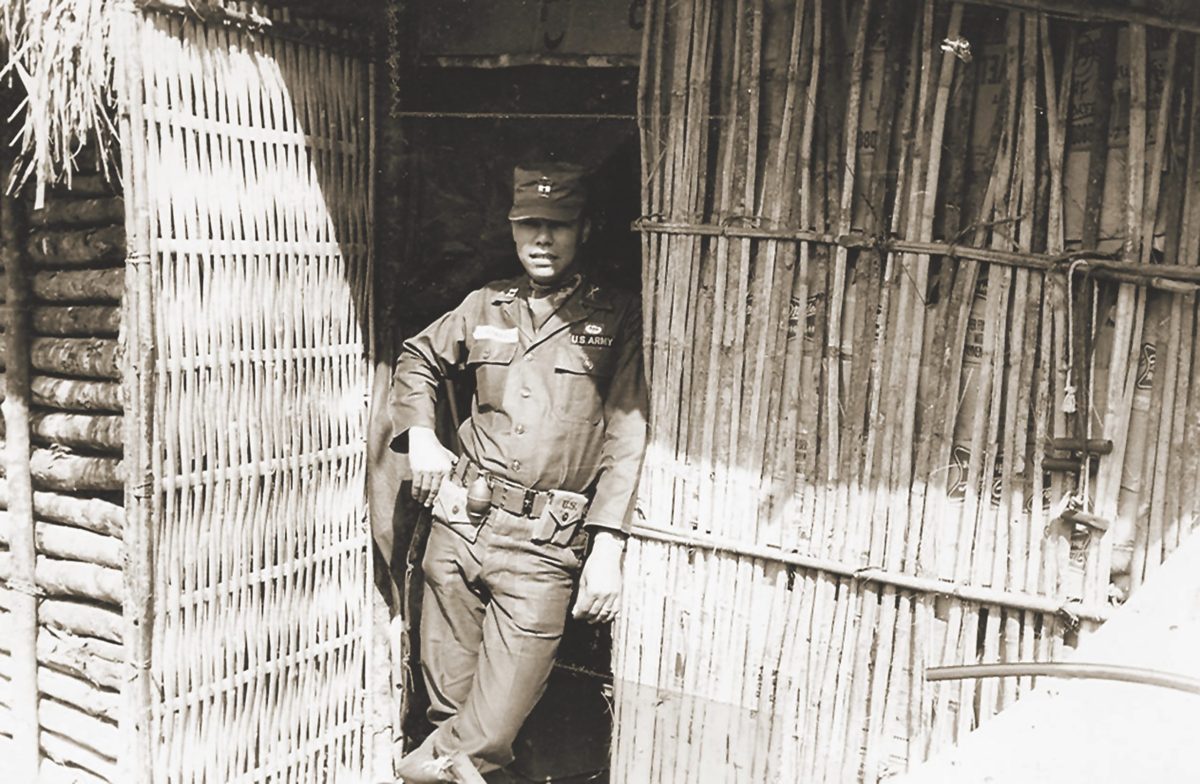

By the time Colin Powell arrived in Saigon on Christmas Day 1962, he was confident and eager for the opportunity to demonstrate the skill and bravery of a well-trained infantry officer, indoctrinated to “march into hell, if necessary, to accomplish the mission.”

Powell was a senior tactical adviser to the 2nd Battalion, 3rd Infantry Regiment, 1st Division, Army of the Republic of Vietnam. That ARVN unit executed counterinsurgency operations against Vietnamese communists in the highly contested A Shau Valley near the Laotian border. During this tour, Powell advised three successive Vietnamese commanders. He adapted his behavior to fit their leadership styles and levels of competency.

Powell developed a close bond with Capt. Vo Cong Hieu, a respected commander of the 2nd Battalion. Hieu appreciated Powell’s counsel on training, fortification techniques and combat tactics. Powell worked carefully to be “useful without taking over,” he later wrote in his memoir. On long jungle patrols, the battalion came under frequent sniper attack and suffered gruesome casualties. Mindful that he was a role model for the South Vietnamese infantrymen, the American adviser consciously tamed his own anxieties. “Every morning,” Powell wrote, “I had to use my training and self-discipline to control my fear and move on. . . . [A]s a leader, I could show no fear.”

Early in his assignment, when his ARVN battalion was attacked, Powell charged into the jungle in hot pursuit of the enemy, but before long he realized that not a single soldier had followed him. On another occasion, when his battalion was on patrol, a U.S. Marine helicopter gunner accidentally killed two soldiers in Powell’s unit. “This bloody blunder had undermined their belief in me,” Powell recalled. But his credibility rebounded when a U.S.-made protective vest saved a Vietnamese private on lead patrol. Powell had insisted that the vest be worn. Thereafter, soldiers hailed the American as “a leader of wisdom and foresight.”

Powell’s second Vietnamese commander, Capt. Kheim, was egotistical and rash, uninterested in the counsel of his American adviser. Powell and Kheim had opposing leadership styles. Powell delighted in developing bonds with rank-and-file soldiers. He even led them in song on a Saturday night. Kheim’s impersonal and ineffectual command came to an abrupt end when he was wounded during a mortar attack. “No great loss to the profession of arms,” his American adviser thought.

Powell’s third Vietnamese battalion commander, Capt. Quang, was capable but lacked rapport and combat credibility with his 400 soldiers. Powell, on the other hand, possessed both expertise and field experience, and he enjoyed the confidence of the troops. The battalion’s sergeant major began looking to Powell for leadership. “I was supposed to be an advisor, not the leader,” Powell wrote. “Nevertheless, the two of us were in quiet collusion. Leadership, like nature, abhors a vacuum. And I had been drawn in to fill the void.”

Powell’s battalion engaged in a rare and successful ambush against a Viet Cong patrol. The adviser’s utter dedication to mission was evident in his willingness to participate in the torching of South Vietnamese villages, the slaughtering of livestock and the destruction of farm fields. “This was counterinsurgency at the cutting edge,” Powell later boasted. He did, however, draw a moral red line at corpse mutilation, advising his soldiers to discontinue the practice of cutting off enemy body parts.

Powell’s unofficial command of the 2nd Battalion ended abruptly in July 1963, when he stepped on a punji spike that pierced the instep of his right foot from bottom through top. He managed to hike to a U.S. Special Forces camp, where a helicopter evacuated him. According to Army records, “Despite this wound, Captain Powell continued to perform his advisory duties and remained with the unit until they arrived at the final destination.” Powell served the remainder of his tour as an assistant operations and training adviser at the ARVN 1st Division headquarters and as the airfield commander at the Hue Citadel airfield.

Powell’s superior officers, American and South Vietnamese, wrote glowingly of his effectiveness. The Vietnamese commander of the 1st Division noted that despite the “arduous and hazardous” jungle environment, Powell had displayed “determination, physical stamina, and professional competence” that contributed to his unit’s killing of “many Viet Cong” and the destruction of enemy “supply bases, crops and live-stock.”

U.S. commander Lt. Col. Joseph O’Connell wrote that Powell was “a tireless worker, cheerful and enthusiastic,” someone who exhibited “a professional touch not normally found in the work of an officer of his grade and time in service.”

The Army awarded Powell a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star. He left Vietnam with no misgivings about the righteousness of his conduct and the broader American mission: “I was leaving the country still a true believer. . . . The ends were justified, even if the means were flawed.”

Reassigned to Fort Benning, Georgia, Powell participated in rigorous advanced airborne Ranger training, which marked an Army officer as “an elite within an elite” group of paratroopers. Powell, despite a fear of jumping from aircraft, finished at the top of his class.

One blustery winter night, he and his classmates were aboard a helicopter preparing for a parachute jump. It was the jumpmaster’s responsibility to check the static lines of all jumpers, but it was Powell who decided to examine each man’s line. He discovered that a sergeant’s hook remained unattached to the floor cable, a potentially deadly oversight. From that experience, Powell concluded, “Don’t be afraid to challenge the pros. . . . Moments of stress, and confusion, and fatigue are exactly when mistakes happen. And when everyone else’s mind is dulled or distracted the leader must be doubly vigilant.”

After completing the advanced airborne course in early 1964, Powell remained at Fort Benning through the summer of 1967. He served as a weapons and equipment tester, completed the Infantry Officers Advanced Course and taught at the Infantry School. At the highly competitive Infantry Officers Advanced Course, which Powell thought “inspired and intimidated in about equal doses,” he impressed his instructors and classmates. Col. Tyron Tisdale, who believed Powell was destined for high command, described him as “a most outstanding young officer” with a “pleasing” personality.

Despite such superlatives, Powell himself recognized a professional shortcoming. He was not an independent critical thinker, not someone who thought beyond the tasks the Army put before him. He confessed to being “just another unquestioning captain, learning my trade.”

Powell graduated from the Advanced Course third in a class of 400 captains and was rated the top officer from the infantry branch. His distinguished performance led to an early promotion to major and appointment to the faculty of the Infantry School. In this assignment, which included a teacher training course, Powell greatly improved his presentation skills, learning to project his voice with authority and command center stage.

“If I had to put my finger on the pivotal learning experience of my life,” Powell later reflected, “it could well be the instructors course, where I graduated first in the class. Years later, when I appeared before millions of Americans on television . . . I was doing nothing more than using communicating techniques I had learned a quarter century before . . . at Infantry Hall.”

Powell incorporated firsthand “lessons learned in Vietnam” into his curriculum. Students rated Powell’s courses among the best at the school.

Steve Pawlik, a fellow faculty member, observed that Powell’s friendly disposition and personal connection with students made him an ideal classroom instructor. “I used to kid him about being [a combat] adviser in Vietnam,” Pawlik recalled. “He was misassigned as an infantry-man; he’s not a killer by nature. He’s a mediator.”

After nearly four years at Fort Benning, Powell was transferred to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, as a student at the Command and General Staff College. After completing the 38-week program, a graduate was expected to know “how to move a division of twelve to fifteen thousand men by train or road, how to feed it, supply it, and, above all fight it,” Powell noted.

Powell also gained insight into his own combat decision-making, which later evolved into the so-called Powell Doctrine. Wargaming at the school, Powell later wrote, “revealed a natural inclination to be prudent until I have enough information. Then I am ready to move boldly, even intuitively. . . . For me, it comes down simply to Stop, Look, Listen—then strike hard and fast with all the power you need.”

Powell was second in a class of more than 1,000 officers, most of whom were senior in age, rank and experience. His picture appeared in the Army Times newspaper.

Powell graduated from the Command and General Staff College in spring 1968. By mid-June he was assigned to the 3rd Battalion, 1st Infantry Regiment, 11th Infantry Brigade, 23rd Infantry Division (Americal), in Duc Pho, an area of northern South Vietnam that was a Viet Cong stronghold. American casualties were numerous.

Powell served as a staff administrator, first as the executive officer for the 3rd Battalion and then as a planning and operations officer at Americal headquarters. As the battalion executive officer, Powell was tasked by his commander, Lt. Col. Henry Lowder, with bolstering the unit’s combat capabilities by mastering its troublesome bureaucracy. One of his numerous managerial duties was to transport infantrymen, weapons and supplies to the battlefield. “He quickly took over” Lowder recalled, “absolutely did a fine job, and I had absolutely nothing to worry about.” Because of Powell’s bureaucratic streamlining, the once poorly managed 3rd Battalion was rated the best unit by the division’s inspector general.

The commander of Americal’s 11th Infantry Brigade, Col. Oran Henderson, praised the major in an October 1968 evaluation report: Powell “has demonstrated constantly his complete competence, level-headedness, and dependability. . . . MAJ Powell is an outstanding officer in every respect.”

The Americal Division’s commander, Maj. Gen. Charles M. Gettys, described Powell as an executive officer who, “in an amazing short time, revised and strengthened existing procedures, and required high performance standards. . . The level and quality of administrative and logistical support increased, thereby creating a higher state of morale among the troops in the field.”

Powell’s accomplishments as a battalion staff officer were especially remarkable given that he served in that position for only three months. Gettys, after reading an old Army Times article, discovered that Powell had graduated second in his class at Fort Leavenworth and immediately reassigned him to Americal headquarters in Chu Lai. Powell began serving as Gettys’ interim G-3, his top operations and planning officer.

“Overnight,” Powell later wrote, “I went from looking after eight hundred men to planning warfare for nearly eighteen thousand troops, artillery units, aviation battalions, and a fleet of 450 helicopters.” Eventually, a more experienced senior officer replaced Powell, but the major remained on Gettys’ staff as deputy operations officer.

In mid-November 1968, Powell accompanied Gettys on an inspection of a captured North Vietnamese base camp. Gettys’ pilot attempted a difficult jungle landing, and the helicopter’s rotor blade struck a tree trunk, causing the helo to crash. Powell fractured his ankle but managed to pull Gettys from the smoking wreckage. With the help of others at the scene, he also rescued the general’s aide, his chief of staff and one of the pilots, all seriously injured. Powell earned the prestigious Soldier’s Medal for heroism.

While working at Americal headquarters, Powell impressed higher-ranking officers. Armed with maps and charts, but never relying on notes, he demonstrated extraordinary presentation skills as he gave briefings on combat readiness, plans and operations.

Col. John W. Donaldson, Americal’s chief of staff, praised Powell as “the finest Major I have known and clearly one of the most outstanding all-round officers I have served with.. . . . [P]ossessing great poise, he is a gifted speaker and talented writer. . . . [O]ne of those rare officers who should be marked for positions of the highest responsibility and promoted to General Officer rank ahead of his contemporaries.”

In May 1969, as Powell approached the end of his second tour, Gettys described him as the most outstanding staff officer he had ever worked with and the best “briefer I have ever known.” Powell had earned a reputation, Gettys wrote, for “working arduous extra-duty hours seven days a week, intense mental pressure and frequent exposure to hostile fire while visiting troops. . . . He always maintained his calm and cheerful attitude, never reflecting the strain of his great responsibilities.”

However, after 11 years in the Army, Powell recognized that even as a highly decorated major he had not yet developed a proclivity for independent thought or a willingness to question superior officers. He had witnessed but not objected to pervasive “poor management practices” that egregiously promoted style over substance in the Army.

Powell also gave blind support to U.S. foreign policy and the military’s strategies and tactics in Vietnam. “I had no penetrating political insights into what was happening,” he acknowledged later.

In his 1995 memoir, after chronicling his unit’s actions in South Vietnam, Powell wrote: “However chilling this destruction of homes and crops reads in cold print today, as a young officer, I had been conditioned to believe in the wisdom of my superiors, and to obey. I had no qualms about what we were doing. . . . It all made sense in those days.”

Powell’s conformity and submissiveness also reflected his intense ambition. “A corrosive careerism had infected the Army; and I was part of it,” he wrote.

Those attitudes governed Powell’s small role in the Army’s cover-up of atrocities in the March 16, 1968, My Lai massacre, in which 500 defenseless Vietnamese civilians, mostly women, children, infants and old men, were brutalized and murdered by soldiers of the Americal Division’s 11th Infantry Brigade three months before Powell joined the brigade.

Within hours, word of the disturbing incidents at My Lai spread up the chain of command, reaching the Americal commander, Maj. Gen. Samuel Koster, Gettys’ predecessor. Koster’s senior deputy recommended a formal investigation, but the Americal commander instead directed brigade commander Henderson, Powell’s soon-to-be superior, to conduct an “informal and quiet” investigation. Henderson suspected that his soldiers had killed a large number of civilians, but he conducted a superficial and biased investigation to satisfy his superiors.

The brigade’s after-action report and Henderson’s April 24 written account brazenly praised the unit involved for killing more than 100 Viet Cong soldiers.

In late November 1968, just before his tour ended, Spc. 4 Tom Glen of the 3rd Infantry, 11th Brigade, penned an eight-page letter to the top U.S. commander in Vietnam, Gen. Creighton Abrams. Glen’s scathing broadside, which did not mention My Lai specifically, stated: “Far beyond merely dismissing the Vietnamese as ‘slopes’ or ‘gooks,’ in both deed and thought, too many American soldiers seem to discount their very humanity; and with this attitude inflict upon the Vietnamese citizenry humiliations, both psychological and physical . . . [And] fire indiscriminately into Vietnamese homes and without provocation or justification.”

Several Americal officers, including Powell, were ordered to respond to Glen’s accusations. In a memorandum, Glen’s former commanding officer, Lt. Col. Albert L. Russell, dismissed the substance of the letter and condemned Glen as a coward who waited to level his charges until he rotated out of his unit.

Powell followed Russell’s lead. He wrote that it was “unfortunate that SP4 Glen did not bring these allegations to his immediate superiors or the IG [inspector general] prior to the end of his tour.” Powell admitted that there might be “isolated cases of mistreatment” of civilians but boasted that “in direct refutation of [Glen’s] portrayal is the fact that relations between Americal soldiers and the Vietnamese people are excellent” (emphases added).

In Powell’s 1995 autobiography he did not mention the Glen letter and his whitewashed response to it. Moreover, he chose not to make any reference to his close association with Henderson, who had extolled Powell’s performance.

Powell’s 1968 memorandum responding to Glen’s letter grossly and intentionally exaggerated the state of friendly relations between U.S. soldiers and South Vietnamese civilians.

Powell eventually admitted the truth. In August 1971 he volunteered an affidavit for the war crimes trial of Brig. Gen. John Donaldson, the former Americal chief of staff who had praised Powell. The Army was prosecuting Donaldson for having routinely “killed or ordered the killing of, unarmed and unresisting” Vietnamese civilians from his helicopter.

In his sworn statement supporting Donaldson’s tactics, Powell disclosed, “For the most part, the local population was unsympathetic if not actually hostile to US/GVN [government of Vietnam] efforts. Willingly or unwillingly, they shielded enemy troops and thereby made their detection and identification very difficult.”

Powell’s book defended the practice of shooting male peasants from helicopters. If Vietnamese men, he wrote, wore “black pajamas,” “looked remotely suspicious” and “moved” after a warning shot, they were killed. “Brutal?” Powell asked. “Maybe so. . . . The kill-or-be-killed nature of combat tends to dull fine perceptions of right and wrong.”

In late March 1969, Ron Ridenhour, another Americal veteran, wrote a letter about atrocities at My Lai. He sent copies not just to the Army’s upper echelon, but also to members of Congress, the secretary of state and president. Two months later, Lt. Col. William D. Sheehan, an Army investigator from the Office of the Inspector General, arrived at Powell’s Chu Lai office and conducted a 90-minute interview as part of an investigation into allegations that innocent civilians were killed at My Lai.

Sheehan asked Powell if he knew of or had any records pertaining to operations near My Lai in March 1968. Powell read aloud from Americal’s doctored tactical operation journals for the first three weeks of March. According to Powell, at one point during the questioning his “guard [went] up.” Apparently not wanting to disclose anything that might displease his superiors, Powell brought the interview to a halt. He called Americal’s chief of staff, who instructed him to continue answering questions.

Powell’s small but unhesitating contribution to the My Lai cover-up is hardly surprising. His superiors had clearly set the example. Little in Powell’s personal development or professional training prepared him—much less encouraged him—to critically assess and consciously challenge his leaders. Moreover, to have done so would have derailed his promising career.

In late 1968, Gettys forecast Powell’s long-term future: “It is difficult to say at such a young point in his career that this young officer has general officer potential, but I am certain that he will be a general officer, that he possesses the necessary qualifications, and time and experience will develop his demonstrated potential to the point that he will be promoted to general officer rank.”

Jeffrey J. Matthews is the George Frederick Jewett Distinguished Professor at the University of Puget Sound in Tacoma, Washington. He teaches history and leadership. He also wrote The Art of Command: Military Leadership from George Washington to Colin Powell.

This article appeared in Vietnam magazine’s February 2020 issue.