Through the Eyes of his Daughter Eva.

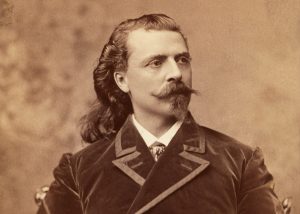

Chris Evans was a brutal, quick-tempered outlaw who robbed trains and never hesitated to spill blood. California newspapers delighted in running stories about him and his primary partner in crime, John Sontag. Chris Evans was also a devoted family man—a tender, loving father. Eva Evans saw Chris’ softer side at home, and, later in life, realized that her father’s legacy bore little resemblance to the man she deeply loved.

As a teenager, Eva Evans played a key role in the sensational saga of Evans and Sontag, although she never took part in any train robberies and might not have realized who was doing the robbing at first. “The circumstances surrounding him were incredible, mad melodrama,” she wrote about her father. “Some writers have been attracted in these latter days by the sheer excitement of the story which has become part of the history of California. But the real story is in the man, himself; the mystery to be unraveled is the accounting for his actions in the light of his known character.”

Born in Bells Corners, near Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, on February 19, 1847, Christopher Evans entered the United States at age 17 because, as he once claimed, “the great struggle for freedom was going on and I left my home…to liberate the slave.” He would later tell stories about his days as a soldier fighting first the Confederates in the Civil War and later hostile Sioux and Cheyenne warriors on the frontier. There is no official record of these activities, however.

After his service, Chris migrated west to California, ending up in Visalia, a significant town in the San Joaquin Valley. During the 1870s, he worked as a teamster, logger, miner and laborer. In 1874 he married Mary Jane (“Molly”) Byrd. By 1886 Chris and Molly had several children, a home on the edge of town, farm acreage south of town and a summer cabin—he called it the Redwood Ranch—in the mountains. Still, like many workingmen, he found providing for his growing family was a constant struggle.

In 1887 Chris met John Sontag, a former brakeman for the Southern Pacific Railroad and, saying he needed help with his horses, offered John a job and place to stay. “I have to be particular who I have, on account of the children,” he added. “I don’t want a man that will swear at my horses, or before my children.”

Chris and John shared a common contempt for the Southern Pacific Railroad. (Indeed, most of the population did. That generous hatred was illustrated by a land dispute at nearby Mussel Slough just a few years earlier—the deadly confrontation between the railroad and settlers immortalized in fiction by Frank Norris in The Octopus years later.) They had specific gripes. Sontag had been injured working as a brakeman, and felt he was unfairly treated afterward. Chris Evans had suffered a farming loss because of unanticipated increases in freighting rates. Although morally a sizable leap, their shared contempt soon led to a partnership in crime.

Eva may not have realized at the time that a rash of San Joaquin Valley train robberies were the work of her father and John Sontag. In February 1889, the two men held up a Southern Pacific train in Pixley. Less than a year later, they committed a similar robbery in Goshen, just a few miles from Visalia. In both robberies, bystanders were killed. In February 1891, a botched train robbery farther south at Alila was attributed to the Dalton brothers, but another holdup in September 1891 at Ceres was the work of her father and John Sontag, to whom Eva was now engaged to be married.

In 1892 the Evans family— there were now seven children—returned to Visalia from an extended stay at the Redwood Ranch, and Sontag’s brother, George, left Minnesota to join them. With his help, the outlaws robbed a Southern Pacific train at Collis (near Fresno). A few days later, on a hot August day, lawmen came knocking on Evans’ door in Visalia. It was 17-year-old Eva who first answered. When her father and John Sontag appeared brandishing weapons, a shootout occurred, and Eva watched as two lawmen were wounded, another killed, and the two men in her life fled.

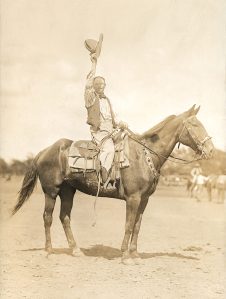

After this, everyone knew that Evans and Sontag were the prolific Central Valley train robbers. Although George Sontag had been arrested, Chris and John escaped to the mountains. The ensuing manhunt would be the biggest in California history. Visalia was overrun by posse members, bounty hunters and reporters. A curious evolution soon occurred. Evans and Sontag, despite the men they had killed, became folk heroes. It was not unlike the mythic rise of Frank and Jesse James in Missouri two decades earlier.

For nearly a year, Evans and Sontag eluded posses in the hills and mountains of California’s Sierra Nevada. There were a couple of near captures when Chris risked all to visit his family in Visalia. There were encounters in the mountains in which gunfire was exchanged. In September 1892, two officers were killed in a fatal shootout at Jim Young’s mountain cabin in Fresno County. Still Evans and Sontag remained at large. Newspapers theorized that the popularity of the fugitives among mountain residents—loggers, miners and ranchers—contributed to their elusiveness. Journalists, including Ambrose Bierce and Joaquin Miller, wrote about them in increasingly sympathetic tones. Although William Randolph Hearst always condemned their criminal activity, he was generous in devoting space in his San Francisco Examiner to their exploits.

Newspapers painted a picture of Chris Evans as an enigma. One article labeled him “Visalia’s Jekyll and Hyde.” Eva saw this as a feeble attempt to analyze her father, the paper offering “the strange transformation from Evans the Farmer to Evans the Outlaw” as evidence of a dual personality. The contradictory elements of his character—brutal outlaw and tender father— certainly contributed to his mythic status.

On June 11, 1893, as the sun was setting, a fierce gun battle occurred at a place called Stone Corral. The next morning lawmen discovered, in a pile of straw and manure, a badly wounded John Sontag. He was taken to jail where he died from his wounds three weeks later. Chris Evans, however, was nowhere to be seen. Eva was proud that her defiant father, after being seriously wounded, walked a couple miles in the dark to a friend’s house. He was captured the next day.

Chris recovered from his wounds, and while he awaited trial, Eva appeared on stage (see related story, P. 52), portraying herself in a popular blood-and-thunder melodrama, reenacting the sensational shootouts and manhunt, a dangerous nighttime ride to the mountain hideout to deliver supplies and information and her doomed romance with John Sontag.

Eva took a break from the melodrama to testify on her father’s behalf, supporting his claim of self-defense in the murder trial for two of the officers killed during the manhunt. Chris Evans was convicted in December 1893. Eva, newspapers reported, “wept bitterly.” Visiting her father in jail a few days later, Eva recalled she “had never seen Dad with such a desperate look in his eyes.” Eva then, with the help of an admirer named Ed Morrell, helped smuggle a gun to her father, who escaped from the Fresno jail just before the New Year.

A fugitive once again, the caring father was ultimately lured back to his Visalia home with false rumor of a sick child, tricked into final capture in February 1894. The saga of Evans and Sontag was finally over, and he began a life sentence at Folsom State Prison.

Eva would later recall her father’s tender side, remembering how she’d watch him walk the floor, reciting Tennyson in his “wonderful singsong voice,” lulling her baby brother to sleep. And she recalled the time her nature-loving father made her promise that when he died, she’d have his body placed inside the giant sequoia in the meadow near their beloved Redwood Ranch.

The love Chris Evans felt for his oldest daughter was apparent when, in 1911, he wrote to her announcing his parole from Folsom Prison. “Cheer up, my darling; we will be having a happy time in the sweet bye and bye.” Chris rejoined Molly and his younger children in Portland, Ore. Eva now lived in Los Angeles with her third husband.

On February 9, 1917, Eva was awakened in the middle of the night by a ringing phone. Her father had died. She took some comfort that he was “free at last from grief and pain,” but wrote that “returning to bed, I cried the night through; not for what had happened, but for what had not. Now I realized fully that I had always clung to the hope that he and I would walk again the paths to the beauty spots at the Redwood Ranch.”

Originally published in the August 2008 issue of Wild West. To subscribe, click here.