On Dec. 21, 1962, the last in a formation of 15 “Flying Bananas,” the nickname for H-21 Shawnee troop transport helicopters, taxied into position at 2:55 p.m. for their scheduled 3 p.m. departure. The 15 helicopters lined up on the Pleiku airstrip in South Vietnam were quite a sight. In a standard 18-aircraft helicopter company, a troop lift involving 10 aircraft was considered normal and 12 was borderline for helicopter availability. A mission with a 15-aircraft request was extraordinary.

The 15 helicopters of 81st Transportation Company, in which I served as a captain and 2nd Platoon leader, would join the 8th Transportation Company the next day on a mission to deliver hundreds of South Vietnamese soldiers to a jungle battlefield. This mission would also deliver an awful blow to both helicopter units.

The 81st Transportation Company had arrived in Vietnam early in October 1962 and was assigned to Pleiku in the Central Highlands after gaining experience in mountain flights while stationed in Hawaii. The five H-21 companies in Vietnam had a total of 90 aircraft. Each was in high demand for air transport missions required to support South Vietnamese troops and the increasing number of American advisers.

Sometime around Dec. 12, our company had received a warning order—an alert to prepare men and equipment for a mission that would be explained more fully later—from Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, in charge of all U.S. forces in South Vietnam. MACV demanded a total of 30 H-21s from the 81st and 8th Transportation companies. At that point in the war, it would be the largest troop lift conducted in Vietnam.

The warning order, classified “Secret” (only for those who “need to know”), stipulated that the 81st would be responsible for coordination and logistics. The 81st also would lead the mission. The briefing date, time and place were “to be announced.”

The order for 15 aircraft from each company was a tough one to fill. The H-21 was a difficult helicopter to maintain. An estimated 11 hours of maintenance was required for every hour of flight. Thus, we immediately prioritized our flight schedule and reduced our missions to “essential flights only.” The mission demands meant that every available pilot would have to fly—including the company commander, executive officer and even the operations officer, who despised the H-21 and flew as seldom as possible.

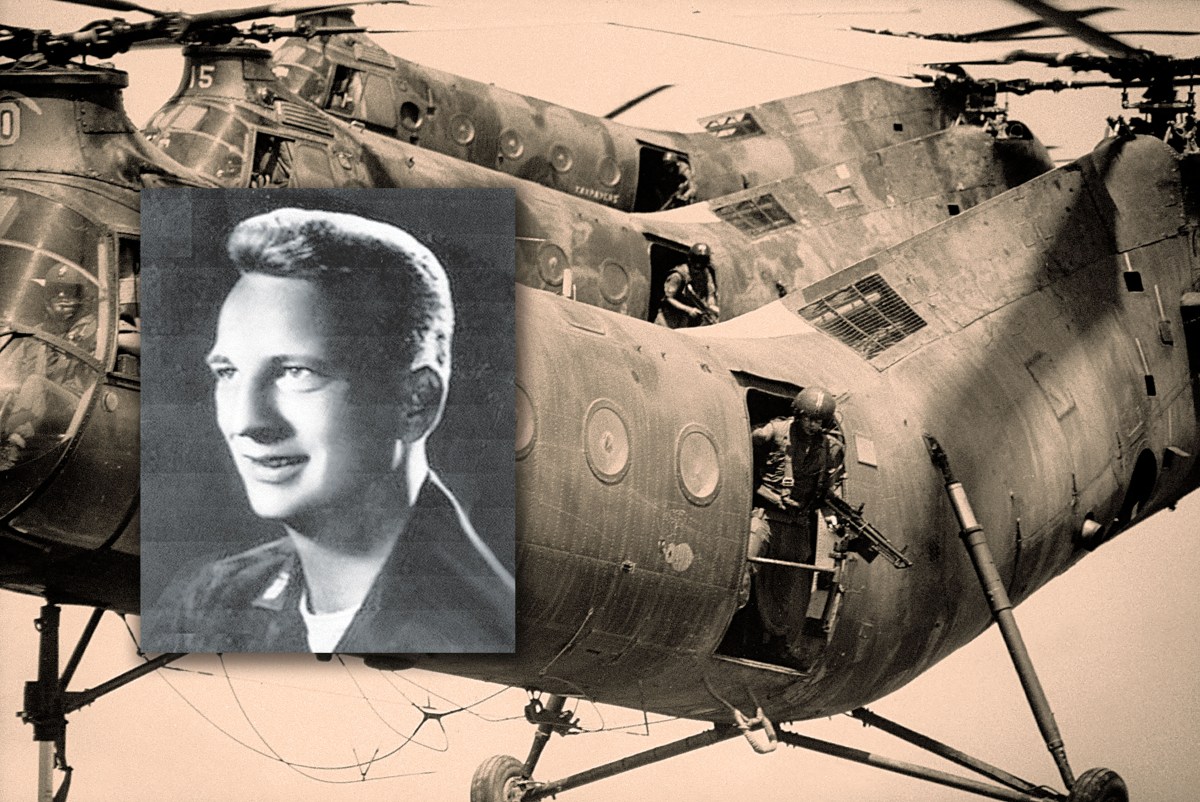

The one pilot who should not have been flying was Chief Warrant Officer Charles Edward “Charlie” Holloway. He had arrived in Pleiku the previous week. Although Holloway was experienced in flying cargo helicopters, that experience had been in the single-rotor H-34 Choctaw, not the two-rotor H-21 Shawnee. The mechanics of flying single-rotor and tandem-rotor helicopters are so dissimilar that Holloway needed more transition training to master the H-21—something that should have been done before he left the States.

The one pilot who should not have been flying was Chief Warrant Officer Charles Edward “Charlie” Holloway. He had arrived in Pleiku the previous week. Although Holloway was experienced in flying cargo helicopters, that experience had been in the single-rotor H-34 Choctaw, not the two-rotor H-21 Shawnee. The mechanics of flying single-rotor and tandem-rotor helicopters are so dissimilar that Holloway needed more transition training to master the H-21—something that should have been done before he left the States.

In Vietnam, Holloway received just two hours of touch-and-go landings as his transition training because he arrived at the 81st Transportation Company during the “essential flights only” order. Under normal circumstances, Holloway’s meager experience with the H-21 would have barred him from flying a combat troop lift. Yet these were not “normal circumstances,” and Holloway would fly.

Midafternoon on Dec. 19 the company clerk told me to report to the commander’s office. When I arrived, the 81st’s commanding officer, Maj. George W. Aldridge, was in a conference with the executive and operations officers. I was waved in, directed to take a seat and handed the MACV warning order of Dec. 12. Aldridge said the time and place for the mission briefing had been received. He wanted me, as the designated mission leader, to attend the briefing, which would be conducted in Nha Trang, about a one-hour flight from Pleiku.

Early the next morning, wearing my last set of starched fatigues, I climbed into the back of our company-assigned L-19 Bird Dog—a spotter plane normally used for reconnaissance and directing airstrikes—and flew to Nha Trang, a coastal city in central South Vietnam.

I arrived early at the briefing building, and the lieutenant colonel in charge was making final preparations in a large conference room. After about 10 minutes or so, four high-ranking South Vietnamese officers and two American bird colonels entered. They seated themselves in leather upholstered armchairs aligned in the front row. I sat to the side in a metal folding chair but also in the front row.

The briefing officer explained that three infantry battalions from the Army of the Republic of Vietnam were to be airlifted to three landing zones north of Tuy Hoa, a small fishing village above Nha Trang. Thirty helicopters would carry one ARVN battalion per lift. The first lift would transport the South Vietnamese to a known Viet Cong compound. The second and third lifts would land troops at sites where they were to establish blocking areas to the north and west.

Airstrikes usually pummeled an area around the landing zone to shock the enemy, inflict casualties and make it safer for the helicopters to land. However, this time there would be no advance airstrikes, the lieutenant colonel said, because the strikes would alert the VC to our arrival and give them a chance to escape into the jungle.

Without thinking, I jumped to my feet and interrupted the briefer. Explaining that I was the designated flight leader, I bluntly stated: “Not airstriking the landing zones is a bad idea.”

Immediately, a booming voice from the back of the room said: “Sit down, captain. The decision’s been made.”

That voice came from a man I hadn’t known was in the room—MACV commander Gen. Paul D. Harkins. I made one last attempt to get my point across. “Sir, it’s a bad decision and could get people killed!” Then I seated myself as ordered. I fully expected to be upbraided by the general or one of his minions after the briefing, but nothing was ever said.

Returning to Pleiku, I briefed Maj. Aldridge. I told him MACV planned to land all 30 aircraft together even though I suggested that three flights of 10 aircraft landing two minutes apart would be more manageable in the landing zones. I found it interesting that over the past two months all requests for troop lifts had come through ARVN headquarters in Kontum, but for this mission MACV was running the show and South Vietnam just furnished the troops.

Aldridge wanted all flight crews briefed before dinner and asked if I could be ready. “I’ll be ready,” I replied. At 4:30, in the mess hall, I briefed the H-21 crews as the lieutenant colonel had briefed me at Nha Trang. Predictably, my comrades raised concerns about the questionable decision to not launch airstrikes in the landing zones.

The next morning, Dec. 21, 1st Platoon leader Capt. Don Coggins and I assigned crews to aircraft tail numbers. As we paired pilots, we made sure each helicopter had one of our strongest pilots. Holloway was assigned to fly with Chief Warrant Officer Dan Gressang, among our more experienced pilots. I would fly with Warrant Officer Ernie Bustamente, on temporary duty from Korea. He was a good pilot but had only limited experience in the H-21.

At exactly 3 p.m., 15 H-21s lifted off from the Pleiku airstrip and flew to Qui Nhon, an hour to the east, where we would join the 8th Helicopter Company. Hardly anyone was left in our company’s area at Pleiku because all the pilots and crew chiefs were in the air, along with 15 volunteer door gunners, extra maintenance personnel and our medical section. The first sergeant had to stay behind as the ranking man in the company area. He was not happy about it. We would bunk that night with the 8th Transportation Company.

At exactly 3 p.m., 15 H-21s lifted off from the Pleiku airstrip and flew to Qui Nhon, an hour to the east, where we would join the 8th Helicopter Company. Hardly anyone was left in our company’s area at Pleiku because all the pilots and crew chiefs were in the air, along with 15 volunteer door gunners, extra maintenance personnel and our medical section. The first sergeant had to stay behind as the ranking man in the company area. He was not happy about it. We would bunk that night with the 8th Transportation Company.

Approximately 10 minutes out, I called Qui Nhon tower, requesting landing instructions for 15 aircraft. The tower cleared us to land to the north but wanted confirmation that there were indeed 15 helicopters. Such a large grouping of H-21s in a single flight came as a surprise. We closed our formation, which was at least a half-mile long, and on final approach slowly reduced altitude and airspeed as we flew the entire length of the runway. All aircraft touched down at the same time, and the tower complimented us for putting on a good show. We taxied to the ramp and held a 10-minute crew briefing on the next day’s schedule: breakfast at 6 a.m., preflight 7 a.m., start engines 7:50 a.m., taxi for takeoff 8:10 a.m.

“See you in the morning,” I said after the briefing, and went into Qui Nhon.

The city had good seafood restaurants, so many of us took the rare opportunity to have a lobster dinner, drink some beer and see old friends from the 8th Transportation Company, where some in the 81st had served previously.

Early in the morning of Dec. 22 the ramp was full of crews preparing for the flight to Tuy Hoa. Bustamente checked our aircraft while I coordinated with the 8th’s flight leader. We would be the Alpha and Bravo flights for the mission to Tuy Hoa, the 81st being Alpha. At exactly 7:50 a.m., we saw exhaust flames as the ramp full of H-21s started their Wright R-1820 Cyclone engines.

Suddenly there was an ear-piercing scream. It sent chills up our spines and caused crews to freeze in place. The scream lasted maybe four or five seconds and then dead silence. We soon learned that a relatively new pilot with the 8th suddenly remembered he had not checked the flight controls for freedom of movement, something only done before the engine is started. With an engine running, raising the pitch causes it to overspeed at extremely high RPM—hence the loud scream. The error destroyed the H-21’s engine. Our group was reduced to 29 Flying Bananas.

At 8:10 a.m., Alpha began taxiing for the hour-and-10-minute flight to Tuy Hoa. Bravo would be just minutes behind. The morning was crystal clear as the sun rose over the South China Sea. Our flight along the coast gave us a beautiful view of Vietnam. Upon arrival at Tuy Hoa, we were surprised to find a 4,000-foot paved runway about 5 miles from the coast. We could see the mountains to the north, where we would be dropping off troops in less than two hours. They appeared to be about 20 miles away.

Alpha flight landed on the south side of the east-west runway, facing east. Bravo landed on the north side, also facing east. Three South Vietnamese battalions, maybe more, were already at the airfield. Fuel truck crews topped off the helicopters. If everything went well, we would make three lifts without refueling.

The first lift was scheduled for 11 a.m. The Flying Banana could hold about 20 Vietnamese troops, but we had decided on just 11 per aircraft to keep the weight down on the first lift when we had full fuel loads. However, we were now one aircraft short and saw more South Vietnamese troops than expected. We increased the load to 12. The generally smaller size of Vietnamese soldiers compared with most Americans enabled us to add the extra man and still stay several hundred pounds under maximum takeoff weight. As we reduced weight by burning off fuel, we could increase the number on lifts two and three, if necessary. To make more room, we removed most of the seats so the troops would sit on the floorboards, which also helped them board and disembark faster.

Engine start time was 10:50 a.m. I was disappointed the Bird Dog pilot did not land and brief us on the size and shape of the landing zones—always-standard procedure on prior lifts. Alpha and Bravo flights lifted off precisely on schedule. At the last minute, an American adviser and a New York Times reporter climbed aboard our aircraft and took two of the four seats not removed. Having two extra passengers put us at max takeoff weight.

After taking off in a loose, staggered right formation, we climbed at about 70 mph to 2,500 feet and headed north toward the mountains. I made radio contact with the Bird Dog pilot, who would give us direction and distance to the landing zone. When the trail aircraft advised me the flight was formed, we increased to about 90 mph, the best speed for close formation flying.

As we approached the mountains, the terrain rose toward us. We were soon flying at treetop level, which is not a good time to be looking down at a map, so we relied on the Bird Dog pilot. He let us know when we were about 10 miles away and told us our course was good. At about 6 miles, he suggested a slight right turn of 5 degrees, and at 3 miles we were straight on course.

I began reducing airspeed at 2 miles from the landing zone but was careful not to slow so much that aircraft in back would have to hover. At treetop level and flying slightly uphill, I couldn’t see the landing zone. Even at slow air speed, I was concerned we might overfly.

Suddenly there it was—and damn, plenty wide but not deep, which means you don’t have much depth in which to cut your speed as you descend. An instant decision had to be made.

I announced, “We’re landing!”

The first three aircraft landed without issues. The next two overflew the zone. All remaining helicopters landed without difficulty because the landing zone farther to the right was both wide and deep.

As the H-21s prepared to land, the crew chief and door gunner opened fire with .30-caliber Browning machine guns. Shots came back at us, and I heard the cries of other crews: “We’re taking heavy fire. I’ve got wounded on board. Let’s get out of here!”

I transmitted: “When you’re unloaded get out! We’ll form up in the air!” It didn’t make sense to sit empty and be shot at just to leave as a group.

Bustamente and I were still unloading our troops. Although we were first to land, we were slow departing. Some South Vietnamese soldiers refused to get off. The New York Times reporter was on the floor shaking badly. The American adviser just left him cowering there. When we finally departed, we were lagging well behind the bulk of the flight.

The two aircraft that overflew the landing zone were now on final approach. I advised them not to land. As they passed the landing zone, they said all aircraft were out and the ground was littered with the dead and wounded.

As Gressang and Holloway were accelerating after lifting off, a bullet hit Holloway on the right side of his forehead. His locked seat harness kept him from falling forward onto the controls, but the weight of Holloway’s feet on the pedals meant Gressang had to struggle to keep the aircraft straight.

The crew chief got Holloway off the pedals and removed his helmet. Holloway was unconscious, with his head slumped to the right, filling that side of the cockpit with blood. As Gressang flew, the crew chief applied a pressure bandage on Holloway’s forehead but had little success in slowing the bleeding.

All helicopters returned to the Tuy Hoa airstrip except one that had lost oil pressure and struggled with an overheated engine, forcing a landing about 2½ miles from the airfield. A trailing H-21 picked up the crew and machine guns. Other aircraft reported light to severe damage, including a helicopter with holes in the fuel tank. Some had dead or wounded troops onboard. We needed to shut down and evaluate the situation.

Our company medical officer, Dr. George W. Inghram, and his team were standing by when Gressang landed. The medical team lifted Holloway from his seat and transferred him to a Huey helicopter for a flight to the Army hospital in Nha Trang. Holloway died en route.

When the first lift was completed, 22 aircraft had been hit, ranging from a single bullet hole to 100 or more. On the next lift we could only fly 17 aircraft, but we each added two additional troops. We lifted off with apprehension 20 minutes later and followed the same flight routine, except this time the site was visible well in advance of the landing zone. On a short final approach our crew chief and door gunner opened fire. Thankfully, there was no return fire. After discharging our troops we departed as a flight, feeling a great deal of relief.

We landed at Tuy Hoa and loaded the third lift of troops plus two additional soldiers, then followed the same procedure as lifts one and two. Lift three went smoothly and was uneventful. In all, we airlifted about 860 soldiers.

When our helicopters got back to Tuy Hoa after the third lift, we were low on fuel. Trucks immediately began refueling all flyable aircraft. When two helicopters from the same unit were fueled and determined to be airworthy, they departed for either Pleiku or Qui Nhon. Five

H-21s were not flyable without extensive repair. It took two days to get them out of Tuy Hoa. Two aircraft had their rotor blades removed, were placed on flatbed trucks and driven to Qui Nhon. We never saw them again.

Holloway’s aircraft had sustained at least 40 hits. It was cleaned as best as possible and released to Pleiku. Another H-21 had 103 hits, but remarkably no vital components were struck, although there were dead and wounded inside. Even more extraordinary, only three crew members from both H-21 companies had more than minor injuries.

To describe what had happened as “a shock” would be a tremendous understatement.

On previous missions, we received only a few enemy rounds, which mostly hit the tail sections. We figured those came from South Vietnamese troops we had just landed—maybe they were intentional, maybe not. Until the Tuy Hoa mission, we had not fully realized that we were no longer training for war but were now in a war—where you can get killed.

We all had a feeling of numbness after Holloway’s death. For a week we walked around with grim faces, not many laughs and few smiles. Gressang was especially quiet and kept to himself. However, we stayed busy flying support missions and working hard, the best medicine for a recovery from grief. Eventually even Gressang returned to his normal cheerful disposition. Yet I have to wonder, would we have grieved harder if Holloway had been with us more than a week and we had known him better?

Getting to Know Charlie Holloway

Charles Edward Holloway, born March 2, 1931, was 31 when he died on Dec. 22, 1962. Holloway lived in De Leon Springs, Florida. He enlisted in the Army and went to flight school. He and his wife, Olive, had five children. Holloway was the 22nd combat death in Vietnam and the fourth Army aviator killed by hostile fire. On July 4, 1963, in a ceremony at the Pleiku airstrip, headquarters of the 52nd Aviation Battalion, the airstrip was named Holloway Field. Later, the surrounding base was named Camp Holloway.

It’s been nearly 60 years since the events of Tuy Hoa, and while I have often thought about that mission, it has occupied my mind more and more the past few years. Maybe I’m writing about Tuy Hoa to answer questions that remain in my own mind. Did the decision to not pre-strike the landing zone really catch the VC by surprise? Or had they already known we were coming and decided to attack us there? Our experience in Vietnam would prove time and again that keeping combat operations secret was nearly impossible.

Then there is the question of my split-second decision to land versus circling to land. Would the VC have left the area while we circled? Or would that have just given them more time to prepare? We’ll never know, but I do know that if they had more time to prepare, a bad situation could have been far worse. Finally, as flight leader, had I done my job properly? I take some comfort in feeling I did it to the best of my ability. V

Thomas R. Messick, a retired major, served for 28 years as an Army aviator, including two tours in Vietnam. Later he retired as manager of flight operations and chief helicopter pilot for General Electric Co. He lives in Prescott, Arizona.

This article appeared in the October 2020 issue of Vietnam magazine. For more stories from Vietnam magazine, subscribe here and visit us on Facebook: