[dropcap]J[/dropcap]ames R. Chalmers was not satisfied. The Mississippian had enjoyed a long, successful life, making his name and fortune as a lawyer and a planter; as a vocal member of the Mississippi Secession Convention and then as a Confederate general; and after Reconstruction as a multi-term representative in Congress. But by the 1890s, he longed for one more commodity: justice.

Chalmers was famously prickly about his honor and reputation, but self-worth was not his focus now. Rather, he was interested in making sure the men he had commanded got their due, primarily for what they accomplished at the April 1862 Battle of Shiloh. As the 20th century approached, the U.S. government had begun the process of creating national military parks at several sites, including Shiloh, and the Confederate representative on the commission overseeing the work, Robert F. Looney, had contacted Chalmers for input on where the Mississippians of his brigade should be fittingly memorialized. “Please see that justice is done my Brigade in marking its position in the Battle of Shiloh,” came the general’s prompt response.

In an earnest letter to Looney, Chalmers detailed the fighting his men had endured during the battle. Describing a series of actions, he repeatedly declared, “Please mark my Brigade at that place” or “Mark that place.” Other Shiloh commanders would act similarly with their reminiscences to the park commission, of course; some even visited the battlefield to mark specific locations. But Chalmers had perhaps a higher claim in this case. In his mind at least, they were rightly the Army of the Mississippi’s “fightenest” brigade at Shiloh.

[quote float=”left”]Bragg organized the brigade under Chalmers in early March, giving it the sobriquet ‘High Pressure Brigade’[/quote]

The unit that Brig. Gen. James Chalmers led into action at Shiloh on April 6, 1862 (2nd Brigade, 2nd Division, 2nd Corps) consisted primarily of Mississippians from across the state—four of its five infantry regiments. The 52nd Tennessee and Captain Charles P. Gage’s Alabama Battery formed the rest of the brigade.

Chalmers and his men had spent the early months of the war with General Braxton Bragg in Florida, but headed for Tennessee after the February 1862 Confederate debacles at Forts Henry and Donelson. Bragg came, too, and organized the brigade under Chalmers in early March, giving it the sobriquet “High Pressure Brigade.” Chalmers’ troops would be part of the massive force that Army of the Mississippi commander Albert Sidney Johnston was assembling for an advance on Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s Army of the Tennessee near Pittsburg Landing, Tenn. Chalmers was sent a few miles north as an advance force at Monterrey, about halfway between Corinth, Miss., and Pittsburg Landing.

When Johnston put his grand gamble in motion on April 3, Chalmers’ Brigade was pulled along as the army passed through Monterrey. But it was a miserable and delayed advance for all, with Chalmers writing that at one point his troops endured “a hard, drenching rain, as the orders to march had been countermanded on account of the darkness and extreme bad weather.” Johnston was forced to order a temporary halt to the operation, a delay many later believed was a big factor in the battle’s outcome. Regardless, by the evening of a comparatively dry April 5, the Confederates were camped not far from Pittsburg Landing, coiled to strike the next morning. Positiioned on the far right of the second line in Brig. Gen. Jones M. Withers’ Division, Chalmers’ Brigade bivouacked “in a little Hollow just South of the…Bark Road.”

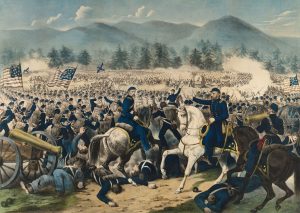

Johnston’s long-awaited attack began at dawn on April 6. The first wave caught the Federals off-guard, but they had begun establishing a response by the time Chalmers’ men moved forward. Chalmers’ men were aligned behind Brig. Gen. Adley H. Gladden’s Brigade, composed mainly of Alabama regiments. Gladden had run into stiff resistance from Brig. Gen. Benjamin Prentiss’ 6th Division in Spain Field, and he would be mortally wounded during the assault.

Chalmers was in the line of fresh troops sent in to turn the tide. He pushed his brigade “by a gradual left wheel” across what 10th Mississippi Colonel Robert A. Smith described as “a thick patch of briars.” Smith, a native of Scotland, advised his men to “divest themselves of their blankets and fix bayonets,” and the other regiments prepared similarly for action.

The Mississippians and Tennesseans had to cross the Locust Grove Branch valley to engage the enemy. “We had to march down this slope to this branch and on top of a little rise just beyond the branch before we was ordered to fire,” remembered a 15-year-old boy in the 52nd Tennessee’s ranks. “[A]s we came down this slant to the branch, we was under heavy fire all the time.” Despite the resistance, Chalmers maneuvered until he could sweep in on Prentiss’ flank, held at the time by the 18th Wisconsin, in Colonel Madison Miller’s 2nd Brigade.

[quote float=”left”]Chalmers sent his men forward but found the resistance stiff, the terrain unforgiving, and the chances of success negligible[/quote]

Chalmers ordered an attack, but it did not go according to plan. In the 10th Mississippi, Smith instructed his men to shoot only when they were within about 60 yards of the enemy. The Federals fired first, however, and the Mississippians “would not wait to form, but commenced firing and with a loud cheer rushed upon the foe.”

Because of the confusion and since Chalmers personally delivered his directive from the brigade’s extreme right flank, only a portion of the troops heard his command—the 10th Mississippi and then the 9th. The rest advanced later after the first regiments “dashed up the hill, and put to flight the [18th] Wisconsin Regiment,” Chalmers gladly noted. Fortunately, that was enough, and the Wisconsin troops—along with the rest of the Federal brigade and its parent division, Prentiss’—fled to the rear. Smith noted they “did not wait to receive them but broke their line and fled.”

Unfortunately, not all of Chalmers’ troops pursued the retreating Federals. The 52nd Tennessee had bolted during the attack—perhaps because Colonel [Benjamin] Lea’s “horse was shot from under him and he was badly wounded,” remembered one of his men. The Tennesseans, the soldier tried to explain, had been told to withdraw to allow a battery to rake the Union line, but “we stampeded and run up under the mouths of the guns.” Chalmers remembered it much differently, later writing that the regiment “broke and fled in most shameful confusion.” When a new line was formed, only about two Tennessee companies responded.

Chalmers followed the Union retreat almost all the way to Sarah Bell’s cotton field, occupied by what Smith described as “the second line of camps.” There Chalmers soon received new orders. General Johnston, having taken position on the high ground in the 18th Wisconsin camp that Chalmers had just attacked, surveyed the field and reacted to new intelligence indicating more Federals were on his right. Realizing he had to neutralize this threat, Johnston at 10:30 a.m. pulled Chalmers and the nearby 3rd Brigade, under Brig. Gen. John K. Jackson, out of line and sent them on a circuitous route to assault the new enemy flank. Reserve troops, then on the way, would replace the two brigades on the front line.

Chalmers and Jackson marched through rough terrain on the Bark Road to a position astride the Hamburg–Savannah Road, from which they could again outflank the enemy. As Chalmers proceeded through a swamp, “advancing rapidly on the right and gradually wheeling the whole line,” he found Colonel David Stuart’s 2nd Brigade, from Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s 5th Division, in a formidable position among the hills and hollows near the Tennessee River. The brigade took fire from all directions, including, as Smith noted, a “heavy cross fire encounter from our own men formed in line on my left and the enemy in retiring in the swamp beyond.”

Chalmers attacked several successive enemy positions over the next few hours but found the going difficult in the harsh terrain, even though the brigade continued moving, he later reported, “in perfect order and splendid style.” Accordingly, the Mississippians pushed Stuart’s outnumbered Illinoisans and Ohioans slowly back from ridge to ridge, the intervening ravines causing great chaos and disorder on both sides. Because the brigade was so close to the river, fire from Union gunboats added to the mayhem. “The men only saved themselves by throwing themselves on the ground,” Smith later noted.

Somehow, Captain Gage’s Alabama Battery kept pace with the brigade, moving horses, guns, limbers, caissons, and other wagons to wherever Chalmers needed them. But it was not easy. As one cannoneer noted: “We used our horses completely up the first day, and the men too, as we were fighting amongst the highest kind of hills; it was down one hill and up the other and at the bottom of the hills were the ravines, and they were so boggy that a man could hardly cross them, and, in some cases, we had to build bridges so as to enable our battery to cross.”

The going was indeed slow, but by 2 p.m. Chalmers had driven back the Federals, who also faced relentless pressure from Confederate attacks to the west. Chalmers gave his men a short break to refill their cartridge boxes before he and the rest of the army lurched forward once more. “Moving at a double-quick, over several ravines and hills,” he recalled, “we came upon the enemy and attacked him on his flank.”

Eventually, the Mississippians wheeled to the west and took part in the capture of the Union-defended Hornets’ Nest. “[W]e again came upon the enemy camps,” Smith noted, “where after a few volleys a brilliant charge was made and the enemy driven from the main camp back upon his fast retreating forces now in full retreat.”

As the sun sank, the Confederate high command—now under General P.G.T. Beauregard due to Johnston’s death—repositioned their troops to make a final attempt at breaking through the Federal lines. Chalmers again took position on the far right, meaning he would have to negotiate the harsh terrain of Dill Branch during an attack. Chalmers sent his men forward late in the day, about 6 p.m., but found the resistance stiff, the terrain unforgiving, and the chances of success negligible. It was “the heaviest fire that occurred during the whole engagement,” he noted. One of only a few Tennesseans still with the brigade remembered that “we come out near the river when our line seemed to be shot through lengthways with shells or canon [sic] balls and we were scattered like Sheep.” Added Smith:

“[S]everal ineffectual attempts were made to induce a charge, but the exhaustion of the troops was so great and the force in front of infantry and artillery supported by the gunboats to our right so strong that our now weakened line could not attempt [it] and a retreat to the ravine back out of range was ordered.”

With nightfall, most Confederates simply realized nothing more could be done that day and began to move toward the rear to resupply and rest.

Thus was born the controversy over whether Beauregard, by calling off the attacks at that point, had supposedly thrown away a victory Johnston had potentially had within his grasp. The reality was that Chalmers’ men, like the others who tried to cross the ravine that evening, prudently decided to halt on their own. They did not need to wait for the order that Beauregard had indeed issued but wouldn’t arrive until later in the evening. Nevertheless, Chalmers was proud of his men’s accomplishments that day, writing those decades later to Looney: “Be sure and mark that place for we got nearer to Pittsburg Landing than any other Confederate Brigade.”

[quote float=”left”]‘I have been in many pitched battles, but none ever made the same impression on me’ –rebel soldier[/quote]

For both sides, it was a long and wretched night. Finding supplies and rest was difficult enough, but a terrible rainstorm and the perhaps unwise shelling from nearby Union gunboats only added to the duress—“a miserable night spent in the rain” was how Smith succinctly remembered it.

Chalmers’ men bedded down as best they could in what had been Prentiss’ camps at the beginning of the battle, but they were alert by dawn the next morning and ready to renew the clash. While fighting broke out at Jones Field, on the battlefield’s western perimeter, Confederate commanders on the right began organizing their lines—and used their best brigade to buy time. Accordingly, the Mississippians were sent well ahead to locate and disrupt any potential Federal advance in this sector. It wasn’t long before Union troops reached Chalmers in Wicker Field.

Major General Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio had reinforced Grant’s weary army during the night, and was now leading the advance. Although it took some time for Buell’s forces to maneuver across the same daunting terrain of Dill Branch that Chalmers had struggled with the night before, they were at Wicker Field by about 9 a.m. But there they were stopped. Resolute resistance by Chalmers bought enough time for Confederate commanders at both the corps and division levels to meld a line to the south along the Hamburg–Purdy Road.

Chalmers was eventually called back to that main line and asked to confront another daunting challenge. His opponent now was Brig. Gen. William “Bull” Nelson’s 4th Division, from Buell’s army, which had seen no major fighting the day before.

Under the circumstances, Chalmers believed an offensive would be the best approach. But a series of Confederate counterattacks were easily blunted by Nelson’s men. Nevertheless, the fact that the Confederates could mount attacks of any sort after a full day of fighting contradicts the common assertions that have come down through time about the lack of Confederate ability on Shiloh’s second day. It should be pointed out, in fact, that some of those attacks succeeded against the much fresher Federals.

Not surprisingly, Chalmers’ men turned in an impressive performance on April 7. A notable example was a counterattack he led that forced Colonel Jacob Ammen’s 10th Brigade, made up of Ohio and Indiana troops, all the way back toward Bloody Pond.” [W]e advanced firing driving the enemy back to the cover of the woods across the field,” Smith would write.

In the process, Chalmers also drove away Captain William R. Terrill’s Battery H, 5th U.S. Artillery—capturing a caisson and almost the guns. But success was short-lived. The tired Mississippians had to give ground as Nelson and Buell focused more attention and troops on this crisis area.

As the fighting continued to rage, Chalmers at one point took command of a larger group of brigades, leaving his own exhausted regiments under Colonel Smith. “His clarion voice could be heard above the din of battle cheering on his men,” Chalmers later wrote of Smith’s delightful brogue.

Chalmers even made a splendid show of bravery in calling his regiments to attack once more, but, he conceded, “they seemed too much exhausted to make the attempt, and no appeal seemed to arouse them.” When he took in hand the 9th Mississippi’s standard and called for them to follow, however, he declared that “a wild shout [arose and] the whole brigade rallied to the charge.” Unfortunately, Lt. Col. William Rankin, commanding the 9th Mississippi, was mortally wounded during that assault.

Eventually, Beauregard had little choice but to fall back to a new line around the Shiloh Church and Prentiss’ old camps before ordering a withdrawal from the field. The battle had ended. The great Confederate gamble had failed.

Although Shiloh was a harsh loss for the Confederates and claimed one of their most acknowledged generals, Johnston, it won laurels for Chalmers and his brigade. Of the 2,039 men in the ranks the morning of April 6, 1,739 were engaged in the battle, with roughly 445 total casualties. Chalmers had seen action in at least six major firefights on the first day and three or four more on April 7. “Since then I have been in many pitched battles including Perryville, Murfreesboro, Chickamauga & Franklin,” one of Chalmers’ Mississippians later wrote, “but none ever made the same impression on me.” It is no wonder then that Chalmers’ Brigade could be called the “fightenest” in the entire Confederate Army. It is also no wonder why Chalmers, those many years later, was so adamant that Colonel Looney “Mark that place” on the Shiloh National Military Park for his men’s signature contributions.

Timothy B. Smith is author of numerous books, including Shiloh: Conquer or Perish. He is currently working on a book about Benjamin Grierson’s 1863 Union cavalry raid.

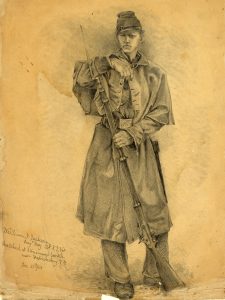

James Ronald Chalmers

Born January 11, 1831, Halifax County, Va.

Died April 9, 1898, Memphis, Tenn.

Education Graduated South Carolina College, 1851

Pre-war

» Lawyer/District Attorney, Holly Springs, Miss.

» Member, Mississippi Secession Convention

Confederate Service

» Entered CSA service as a Captain (1861)

» Promoted Colonel, 9th Mississippi Infantry (March 27, 1861)

» Commander, Confederate forces, Pensacola, Fla. (early 1862)

» Promoted Brigadier General (Feb. 13, 1862)

» Commander, 2nd Brigade, Wither’s Division, Army of the Mississippi (April 6, 1862)

» Battle of Shiloh (April 6-7, 1862)

» Battle of Stones River/Second Murfreesboro (Dec. 31, 1862–Jan. 3, 1863) [Wounded]

» Commander, 5th Military District, Department of Mississippi and East Louisiana (April 1863–64)

» Battle of Collierville (Tennessee, Nov. 3, 1863) [Wounded]

» Commander, Chalmers’ Division, Forrest’s Cavalry Corps (1864–April 1865)

» Battle of Fort Pillow (April 12, 1864)

» Battle of Brice’s Cross Roads (June 10, 1864)

» Battle of Tupelo (July 14–15, 1864)

» Temporary commander, Forrest’s Cavalry Corps (July–Sept. 1864)

» Battle of Nashville (Dec. 15-16, 1864)

» Wilson’s Raid (March 20–April 20, 1865)

» Surrendered as part of Forrest’s Cavalry Corps (May 1865)

Postwar

» Mississippi state senator (1875–76)

» 6th Mississippi District, U.S. House of Representatives (1877–82, 1884)