To protect Washington from menacing Southerners, Maj. John Barnard built a network of forts and gun emplacements. It was only tested once.

Although it was the Union capital, Washington, D.C., was in essence a Southern city. It also wasn’t well-protected, with Fort Washington in Southern Maryland its lone creditable citidel. By war’s end, Washington was one of the world’s most heavily fortified cities. Loretta Neumann, president of the Alliance to Preserve the Civil War Defenses of Washington (www.dccivilwarforts.org), works to keep the history of those forts alive.

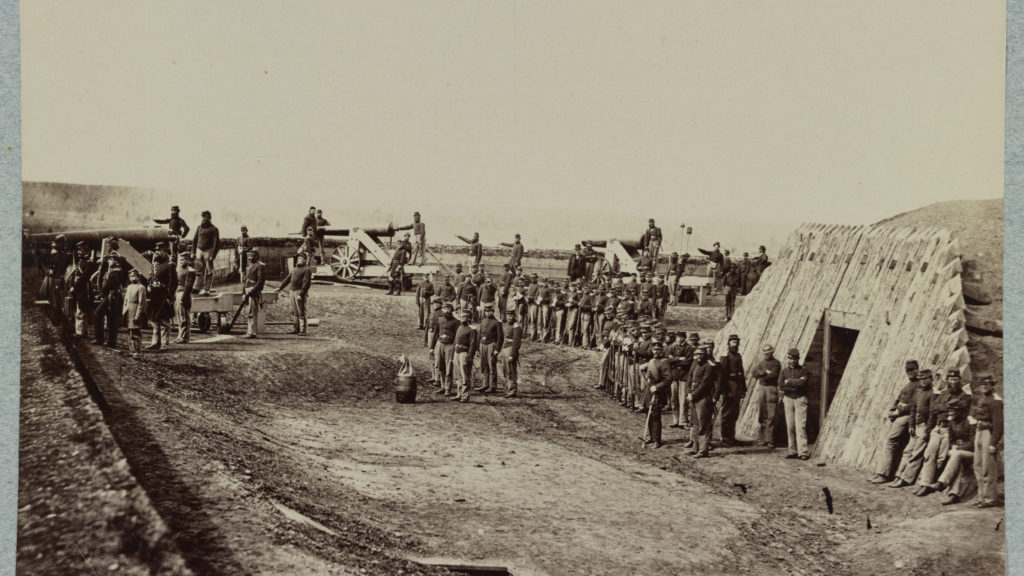

Explain the defensive plan put in place. By the end of the war, there was a 37-mile circle around D.C., with 68 forts, 93 batteries, 807 mounted cannons, 13 miles of rifle trenches, and 32 miles of military roads. Unlike Fort Washington, which was built of brick, the Civil War defenses of Washington were earthworks, usually surrounded by a dry moat, with emplacements for cannons and underground magazines where weapons and gunpowder could be stored. They were built on high ground, which gave them a strategic advantage over enemy troops. They were designed by then-Major John G. Barnard, a West Point-educated Army engineer, who played a significant role in constructing defenses of American supply lines in the Mexican War and succeeded Robert E. Lee as superintendent of West Point.

What kinds of artillery pieces were installed at the forts? The artillery at the forts varied and changed over time. When the forts were first built, they were mounted with large, old siege artillery, including 32-pounder seacoast guns, and various light artillery, including 12-pounder howitzers at Fort Marcy. Parrott rifles of varying sizes were mounted in 1862-63. Fort Stevens was armed with 30-pounder Parrott rifles. Battery Rodgers was armed with 200-pounder Parrott rifles. Rodgers and Fort Foote were armed with 15-inch Rodman guns, the largest guns in the capital defenses. The forts were also armed with coehorn mortars of various sizes.

How much of a deterrent were the forts? The forts were well-placed at spots that commanded major roads. The units assigned to man them drilled constantly. The heavy artillery regiments, or “heavies,” as they were called, did not see much action until Ulysses S. Grant laid siege to Petersburg, Va., in the summer of1864. High casualties in the Overland Campaign prompted Grant to redeploy the heavies from Washington to the front lines as infantry. They were replaced in the Washington forts by inexperienced recruits and convalescents from Army hospitals.

What happened then? Grant’s order to strip the Washington forts of veteran soldiers was a factor in Robert E. Lee’s decision in June 1864 to send Lt. Gen. Jubal Early’s Second Corps through the Shenandoah Valley to invade Maryland and take the war to the gates of Washington. After defeating Union Maj. Gen. David Hunter’s army at Lynchburg, Early led about 15,000 troops north to Harpers Ferry, W.Va. where they were held back for a few days by Union troops and then crossed the Potomac at Shepherdstown. On July 9, at Monocacy Junction, just south of Frederick, Md., Early faced Union Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace and his 3,200 troops from the Middle Department in Baltimore. Wallace was also joined at the last moment by the Third Division of the VI Corps, led by Maj. Gen. James B. Ricketts, whose men hurried north by steamboat and train from Petersburg. The outnumbered Union forces were beaten back, but succeeded in delaying Early by a day. On July 10, 10,000 Confederates marched down Rockville Pike towards Washington, about 15 miles away, to what is now Georgia Avenue NW. Exhausted by the heat and fighting, the Rebels straggled into Leesborough (now Wheaton), Silver Spring, Takoma Park, and what became the Walter Reed Army Medical Center north of Fort Stevens, just inside the northern edge of the District of Columbia. Early decided to delay his attack until July 12.

Explain the Battle of Fort Stevens. Union guns began firing July 11 after the skeleton crews at Forts Stevens, Totten, Slocum, DeRussy, and Reno were joined by civilians, led by Quartermaster Gen. Montgomery Meigs. Meanwhile, more VI Corps troops arrived, and when Early’s troops advanced on Fort Stevens the next day, they ran into veteran artillerymen firing the big guns at full speed. President Abraham Lincoln and Mary Todd Lincoln visited Fort Stevens on both days of fighting. On July 12, a sharpshooter wounded a surgeon standing next to Lincoln, who was conspicuous in his stovepipe hat ashe stood on the parapet. An Army officer supposed yelled “Get down, you fool!” Early realized that the forts were now impregnable and his exhausted army retreated back to the Shenandoah Valley. The capital was safe.

What happened to the forts after the war? Most were dismantled and either returned to their owners, sold, or saved by the government for future needs as forts. The land on which Fort Stevens was built had been taken from a free black woman, Elizabeth (“Aunt Betty”) Thomas; the land was returned to her after the war. Twenty-three forts remain—18 under the management of the National Park Service, and five owned by local governments in Virginia and Maryland. Remnants of some are also privately owned.

What does the Alliance to Preserve the Civil War Defenses of Washington do to preserve and interpret the remainders of the fort system? The Alliance was incorporated as a nonprofit organization in 2008. Our initial role was preservation of these sites, which are so important to both national and local history. Many were eroding due to weather, growth of exotic species, and human activities. As a result of our advocacy, NPS assigned a program manager, whose responsibility was to coordinate activities related to the defenses. Today, however, there is only a tiny staff to manage all these sites—Kym Elder, the program manager; Steve Phan, historian and ranger; plus a ranger who has been assigned temporarily due to the absence of Ranger Kenya Finley.We feel that interpretation of the sites and educational outreach to the public is essential to our mission. We give talks to schools, libraries, and community associations, and we offer at least one bus tour of the sites every year. And every year we help the NPS plan and implement the annual commemoration of the Battle of Fort Stevens, held on a Saturday nearest the original battle. (Next year it will be held on June 11, 2020). We tell the story of the Civil War Defenses of Washington, the Battle of Fort Stevens and much more. Reenactors (both military and civilian), speakers, musicians, exhibitors and others bring to life that whole period of history.

What plans does the alliance have for the future? We hope to see legislation enacted to designate the Civil War Defenses of Washington as a National Historical Park. Delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton, who represents Washington, D.C., in the House of Representatives, has introduced such a bill, HR 3725. We strongly support the legislation as a way to add more protection and resources for the defenses,and we welcome a chance to testify at congressional hearings.

An abbreviated version of this interview appeared in the January 2020 issue of America’s Civil War.