To the casual observer, the Battle of Fredericksburg was a terrible blunder for the Union Army of the Potomac, in particular the daylong attacks on Marye’s Heights: 30,000 troops repeatedly sent 900 yards across an open field, uphill, against Confederate infantry hunkered down behind a formidable stone wall and supported by nearly 50 artillery pieces perched on the heights behind them. By the end of the fighting on December 13, 1862, the Federals had suffered nearly 13,000 casualties, the Confederates fewer than 5,000.

It’s easy to cast blame on Union commander Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside, to decry the loss as a tragic debacle that should have been avoided at all costs. But to dismiss Burnside as a blunderer is to make a blunder. The outcome of the Battle of Fredericksburg was anything but an inevitable fiasco-waiting-to-happen. Going in, Burnside had many legitimate reasons to believe he could win.

To better understand Burnside’s mindset, flash back to September 17, 1862, when the two armies clashed along Antietam Creek in the single bloodiest day of the war. After the battle, Confederate commander General Robert E. Lee slipped his Army of Northern Virginia back across the Potomac River and to the safety of Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. Union Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan decided not to give chase.

Frustrated by McClellan’s inaction, President Abraham Lincoln urged his commander onward, but to no avail—and Lincoln could do nothing about it. The midterm elections were coming up, and things already looked grim for his Republican Party. By disciplining McClellan, a popular Democrat, Lincoln would only make his political situation worse.

But the day after the elections, on November 7, Lincoln sacked McClellan and appointed Burnside in his place. Burnside came to command knowing that his predecessor was fired for not doing anything. As a result, he knew he had to do something or risk McClellan’s fate.

Not only did Burnside have to act, he also had to do so quickly. It was already mid-November, and winter would soon settle in. Once the weather turned, conducting a campaign would be next to impossible.

It would not be enough, however, to march around and rattle his army’s sabers in a show of force. Burnside had to win. Because of the Union victory at Antietam, Lincoln issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which freed slaves in areas of the United States still in rebellion. Of course, the only way to enforce the proclamation and garner public support would be through battlefield victory—otherwise, the president’s lofty plan would be little more than a paper tiger.

So Burnside had to do something, he had to do it quickly, and he had to succeed. Washington’s fervor for battle was so intense that Lincoln’s general-in-chief, Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, said it was better for Burnside “to fight a battle now, even if he is to lose it.”

Rather than follow the Confederates southwest into the Shenandoah Valley, Burnside devised a plan to slip his 118,000 men southeast to Fredericksburg, where he could cross the Rappahannock River, make a quick dash to Richmond, capture the Confederate capital, and, he hoped, end the war. If nothing else, threatening Richmond would draw Lee into battle.

Fredericksburg, a city with a wartime population of just more than 5,000, lay directly between the capitals of Richmond and Washington, D.C. The city was a key component to Burnside’s plan because it had a major railroad and a river; Burnside could use both to supply his army. Fredericksburg also boasted two major roads to the Confederate capital: the Telegraph Road and the Bowling Green Road.

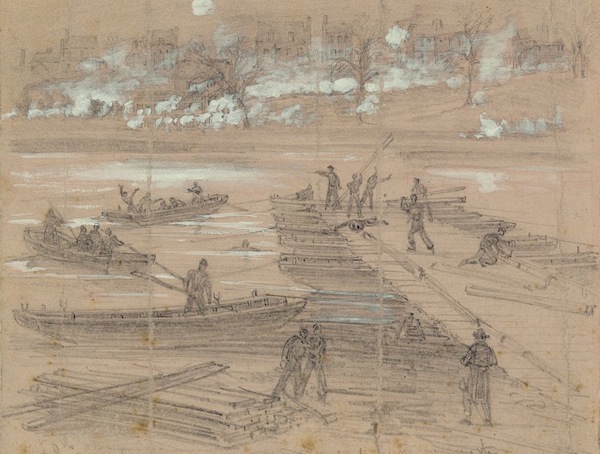

Burnside knew the bridges in Fredericksburg had been burned during a Federal occupation of the city the previous summer. So, well in advance of his move, he asked the War Department to send bridging materials that he could use to span the river.

On November 15, Burnside launched his plan, successfully moving his army to Fredericksburg by November 19. Due to circumstances beyond Burnside’s control, though, the bridging materials had not yet arrived. Poor communication between the War Department and the engineers in charge of the bridging left the materials backed up along a route that stretched from Washington, D.C., to Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. That breakdown in communication would cost Burnside and his army dearly.

When Lee discovered what Burnside was up to, he quickly moved to intercept the Federals. With part of the Confederate army settled around Culpeper, Va., and part of it still in the Shenandoah Valley, Lee ordered the two wings to concentrate. He moved his First Corps, under Maj. Gen. James Longstreet, into the hills behind Fredericksburg—including the area known as Marye’s Heights. These 40,000 men were in a perfect blocking position.

The other half of Lee’s army—the 38,000 men in Maj. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s Second Corps—stretched out some 25 miles toward the south to cover all other possible river crossings. Until Burnside showed his hand, Lee had to prepare for all contingencies.

A quick strike was now out of the question for Burnside because he’d lost the element of surprise—but he still needed to do something.

As he considered his alternatives, Burnside looked downriver. There, the Rappahannock was wider, it was affected by the ocean’s tides, and the road network on the opposite bank wasn’t especially conducive for moving his large army.

Alternatively, if the army moved upriver it would have to cross not only the Rappahannock but also its main tributary, the Rapidan. Meanwhile, Lee could simply shift his army to the northwest to meet Burnside, and then the Union army would face two contested river crossings instead of one. Going in that direction would also move the Union army away from its supply lines.

In short, neither direction looked promising. At least if he crossed at Fredericksburg, Burnside could use the city to shield the army’s movements, giving his men a degree of protection. So, of the options available to him, Fredericksburg offered the best chance for success. “I think now that the enemy will be more surprised by a crossing immediately in our front than in any other part of the river,” Burnside wired Lincoln.

Burnside planned to build pontoon bridges at the north and south ends of town, along with two pontoon bridges about a mile below town (eventually there would be three bridges at that southernmost location). His army would cross at all three places, but Burnside planned to launch his main attack against the south end of the Confederate line, at an area known as Prospect Hill, where the high ground wasn’t as formidable as it was directly behind the city.

To prevent the Confederates from reinforcing the southern part of their line, though, Burnside intended to launch an attack against the northern end of the Confederate position to hold those potential reinforcements in place. He hoped one assault or the other would achieve a breakthrough that would flush Lee’s army from its position and open the southward road toward Richmond.

Burnside set his plan into motion on December 11. The engineers had difficulty building their pontoon bridges because of Mississippi riflemen ensconced in the city. After artillery bombardment failed to dislodge the Mississippians, Union commanders sent several regiments across the river in boats to establish a bridgehead. It would become the first amphibious landing under fire in American history.

Troops from New York and Michigan established the foothold, and from there, the Union regiments fanned out. Street fighting ensued. Losses were heavy on both sides. The 20th Massachusetts, known as the “Harvard Regiment,” lost 163 of 307 engaged. The house-to-house battle lasted more than 3½ hours before the Mississippians were driven back to the main Confederate line. They had held off the Union advance for an entire day, buying crucial time for Lee to concentrate his men.

The Union engineers finished their bridges, but the bulk of the Union army would not cross the river until December 12. Frustrated by the delay, Federal soldiers took out their anger by sacking the city of Fredericksburg. Their commander, meanwhile, frittered away December 12, supervising the advance of his army in and around the city and tweaking his plan.

This delay may have been Burnside’s decisive mistake. Remember, his plan called for an attack on the southern end of the Confederate line—the very section of the line that was weakest, stretched out 25 miles to the south. However, once Burnside tipped his hand by crossing in Fredericksburg, Lee sent word to Jackson to concentrate his Second Corps. Burnside’s wasted December 12 gave Jackson the valuable time he needed to consolidate his position at Prospect Hill.

Burnside intended to launch his attack against Prospect Hill in the predawn hours of December 13 with 60,000 men. Although Burnside cut the orders on the night of December 12, Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin, commanding the army’s Left Grand Division on the southern end of the field, didn’t get them until 7:45 a.m.—35 minutes after dawn.

To make matters worse, Burnside’s orders were vague, saying, “You will send out at once a division at least…taking care to keep it well supported and its line of retreat open.” Although the written orders flummoxed Franklin, who didn’t quite know how to interpret them even though he and Burnside had gone over the plan the previous evening, he failed to ask Burnside for clarification.

Meanwhile, Burnside, unaware that his plan was already unraveling, sent word at about 10 a.m. to Maj. Gen. Edwin V. “Bull” Sumner, commander of the Right Grand Division, to begin the assault at the north end of the line in front of an area known as Marye’s Heights, a ridge that crested about 900 yards beyond the western edge of the city.

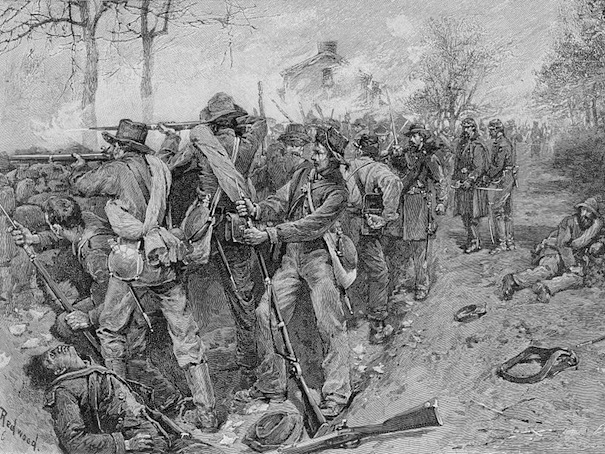

Despite the uphill slope Union soldiers would have to cross, Union commanders saw an advantage to the terrain: The wide-open space contained very few obstructions, which would allow the advancing soldiers to build up momentum for their attack. The plan called for a lightning-fast strike out of the city, across the open plain, and against the Confederate infantry position—a sunken road that ran behind a stone wall some 30 yards below the crest of the hill, held by 2,000 troops from Georgia, under Brig. Gen. Thomas R.R. Cobb. The Confederate pickets out in the field would be so startled by the fast attack that they would turn tail and run back to the line, acting as human shields for the advancing Union soldiers hot on their heels.

The chest-high wall looked imposing, although a portion of it was hidden from Union view because it held up a dirt embankment. Even so, Federals saw a potential advantage to attacking the wall. After all, at Antietam, the Confederates had used a sunken road as a fortified rifle pit, from which they were able to generate a withering fire—but once the Union soldiers broke through, it would be like shooting fish in a barrel. Confederates had no safe route of retreat.

Here in Fredericksburg, the situation would be much the same. If Union forces could breach the stone wall, Confederates could try to retreat, but the only route available would be up the slippery exposed slope behind them or down the Telegraph Road toward Franklin’s force.

In addition, if Union troops could breach the wall, it would give them safety from the artillery fire that would surely rain down from the top of Marye’s Heights. First Corps artillery chief Colonel E. Porter Alexander had nearly 50 guns posted along the top of the heights. “Sir, a chicken could not live on that field when we open on it,” he boasted to his commander, General Longstreet, referring to the expanse the Yankees would have to cross. But if those Yankees got close enough to the stone wall, the Confederate artillerymen wouldn’t be able to depress their barrels enough to fire on them.

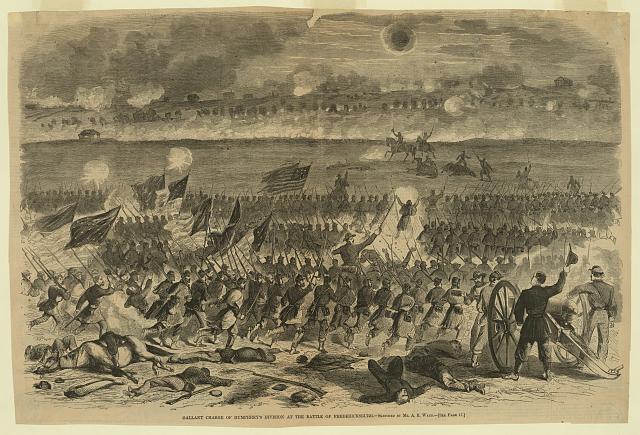

By 11:45 a.m., the first Union troops, under Brig. Gen. William H. French, stepped out of the city toward Marye’s Heights. The 4,500 men in his three brigades immediately came under artillery fire from Alexander’s batteries. “We could see our shells, bursting in their ranks, making great gaps,” said one of the artillerists. A Union soldier said that “it seemed we were moving in the crater of a volcano.” Still, the Union soldiers came on, even as the cannons tore them to pieces.

A millrace cut across the field. Fifteen feet wide and five feet deep, the ditch diverted water from the Rappahannock. Union engineers had blocked off the millrace and tried to drain it, but nearly three feet of water still stood at the bottom. The troops clambered through, then tried to get back into formation before continuing their advance, the artillery ripping into them the entire time.

Another factor the Federals hadn’t considered was the weather. On December 13, the temperature rose to 56 degrees—but several days previously, it had snowed. The subsequent warm weather melted the snow, making the ground wet and spongy and slippery. The smooth-soled boots of the soldiers made footing on the muddy ground even slipperier and the advance more difficult.

When the lead elements of French’s attack neared the stone wall, the Confederate infantry opened on them, halting the advance. “[O]ur men were never subjected to a more devouring fire,” one Union soldier said.

All three brigades in French’s division met the same fate as they tried to brave the “furious storm of shot, shell, and shrapnel.” Nearly a quarter of French’s soldiers would end up as casualties. Survivors took cover in a shallow swale, a dip in the ground about 200 yards downhill of the stone wall.

Still, the Union soldiers came on. At about noon, after French’s attack fizzled, Brig. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock’s 5,000 men were sent in to face the storm of lead coming from the stone wall.

Among Hancock’s men was the Irish Brigade, one of the more famed units to fight at Fredericksburg. Of the 1,200 Irishmen who advanced against the wall, only 256 would survive the assault to answer roll call the next morning. (After the battle, as stragglers and the wounded returned, the brigade’s ranks would increase to just more than 600.) Overall, Hancock’s division suffered 2,000 casualties.

By 1 p.m., Brig. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard’s division, with its 3,500 men, was sent against the stone wall. Brigadier General Samuel Sturgis with 4,475 men of the 9th Corps was sent to support Howard. They suffered 610 and 1,011 casualties, respectively.

Overall, the Union army was suffering a staggering average of 1,000 casualties an hour.

By 3 p.m., Brig. Gen. Charles Griffin’s division, with its 6,000 men, was sent into action. Instead of making the stone wall his objective, Griffin sent his men in piecemeal to relieve Sturgis’ embattled troops. When Griffin finally did decide to attack the wall, he lacked the strength to do it. By the end of the day, his division suffered nearly 1,000 casualties.

By this time, on the Confederate side, nearly 3,000 reinforcements had been sent to the Sunken Road to support the 2,000 infantrymen who had started the battle. To get into position, reinforcements had to descend from Marye’s Heights down a steep embankment that exposed them to Union fire. Most of the Confederate casualties suffered during the fighting would occur on that hillside. For instance, the 8th South Carolina, stationed atop Marye’s Heights, incurred 31 casualties in the battle—28 of them on the top of the hill and on the hillside as they advanced down to the Sunken Road; on the road itself, they sustained only three.

From the Union perspective, it might have looked as though their advances were having an impact. Why else would Confederates send in reinforcements if not because they were feeling the pressure?

In fact, Confederate soldiers were putting so much lead in the air that they were running out of ammunition. To alleviate the problem, Longstreet shifted entire brigades onto the road: Fresh soldiers meant fresh supplies of ammunition. “[I]f you put every man on the other side of the Potomac on that field to approach me over the same line, and give me plenty of ammunition, I will kill them all before they reach my line,” Longstreet boasted.

The Confederate firepower behind the wall was made even more terrible by the efficiency of the infantrymen. Some units lined up four to six ranks deep, with the man in front firing and then going to the back of the line to reload while the second person stepped up to fire. When he did, he went to the back of the line while the third man stepped up, and so on. Thus the Confederates were able to create a conveyer belt–like effect.

Other units put their best marksmen in the front; they would fire, pass their empty muskets to the back while someone passed them a loaded one, which they would fire and again trade for a loaded one. In this way, “[t]he small arms made one continual noise without a moment’s cessation,” a Confederate infantryman said. Another Confederate marksman stated he was black and blue from his right elbow all the way to his right hip for the next two weeks because he fired so many rounds that day.

Meanwhile, at the far end of the field near Prospect Hill, Union troops under the command of Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade—who would eventually command the Union army at the Battle of Gettysburg—finally achieved success. At about 1 p.m., Meade’s Pennsylvania Reserves broke through the Confederate line. However, they were 8,000 men trying to drive through 38,000 Confederates stacked four divisions deep. Meade’s men held for a while, but the Confederates began to push them back.

Meade, confident he could exploit the breakthrough if supported, desperately called for reinforcements. No one came, so Meade rode back himself to look for help. He even verbally assaulted another general who had not marched to his aid.

But it was all to no avail. Meade’s commander, Franklin, had decided his soldiers had had enough and called off the attack.

Yet he didn’t tell Burnside.

And so, Burnside continued to send troops into the meat grinder in front of the stone wall to support an attack at the far end of the field that was not happening.

Burnside was able to see Marye’s Heights from Sumner’s headquarters at Chatham Manor, a large house directly across from the action on the far bank of the Rappahannock; he could not see Prospect Hill, though, obscured by trees, smoke, and distance. The Rappahannock, however, amplified the echoing effect of the sound waves from the battle. As a result, Burnside could hear constant gunfire, but he couldn’t pinpoint the direction from which it was coming. From his perspective, it sounded as if everything at the far end of the field was carrying on as ordered.

Poor communications complicated matters. Although the Union army had strung miles of telegraph line, not everyone trusted the new system, so officers frequently sent couriers, who took a great deal of time to travel from one end of the line to the other.

Eventually, Burnside learned that Franklin had called off the attack and ordered him to resume his offensive, to “advance his whole line.” Franklin, who was as overcautious as his old mentor, McClellan, said he’d see what he could do—but then did nothing.

And again, he did not tell Burnside.

Burnside, however, expecting that his orders were being carried out, continued to throw soldiers at the stone wall to keep those Confederates from reinforcing the far end of their line. And so, what had originally been intended only as a diversion took on a terrible life of its own. By the end of the day, seven waves of Union soldiers would crash against the stone wall and be swept away—18 Federal brigades containing some 30,000 men. Beside French, Hancock, Howard, Sturgis, and Griffin, Brig. Gen. Andrew Humphreys and Brig. Gen. George Washington Getty sent in attacks.

Humphreys’ 4,500 Pennsylvanians attacked with a series of bayonet charges. Survivors of previous Union attacks clung to the pantlegs of the advancing men. “Don’t go forward, it is useless, you will be killed,” one of them pleaded as he lay prostrate behind the swale. For a plan that called for a fast bayonet charge, having fellow soldiers grabbing at the legs of the advancing men tended to be counterproductive.

Still, Humphreys’ men claimed they made it to within 12 paces of the wall. Peter Allabach, a colonel under Humphreys, stated, “My boys made it closer to the gates of hell that day than anyone else on the battlefield.” Subsequent charges got to within 30–45 yards of the stone wall before being repulsed by “a sheet of flames.” Humphreys lost more than 1,000 men in less than 45 minutes.

Getty’s attack came at the end of the day, just after sunset. His men advanced through “(a) perfect storm of bullets, boys; a perfect storm!” according to one Connecticut colonel.

One of Getty’s brigades, under Colonel Rush C. Hawkins, got within 80 yards of the stone wall by sneaking under the cover of darkness up an unfinished railroad cut. In their excitement, the men let out a yell as they neared the wall, giving away their position. “If they had not started with a cheer,” admitted E.P. Alexander, “I don’t think that I, at least, would have known they were coming; for I could not see them.” But thanks to the giveaway, Alexander’s men loaded up with canister, and the volley that ensued shredded Hawkins’ advance.

So ended the fighting on December 13. More than 8,000 Union casualties lay in front of Marye’s Heights. The Confederates had suffered just about 1,000—an 8-to-1 ratio. Nearly one-third of the attacking force became casualties, yet not a single federal soldier touched the stone wall or made it into the Sunken Road.

Meanwhile, at Prospect Hill, which had clearly held Burnside’s best chance for victory, the Union army suffered 4,500 casualties, the Confederates just more than 4,000.

The next morning, Burnside still believed he could achieve victory at Fredericksburg. He convened a council of war with his subordinates and announced that he would personally lead his former troops, the 9th Corps, into battle. Burnside believed that the personal loyalty those soldiers felt toward him would inspire them to follow him anywhere, including across the upward sloping plain toward the stone wall.

Burnside, however, was the only one who felt that way. After doing a personal inspection and talking to several officers, “I found the feeling to be rather against an attack…” he said, “in fact, it was decidedly against it.” Ultimately, a teary-eyed Burnside called off his plan.

Therefore, December 14 passed with Confederate soldiers behind the stone wall trading pot shots with Union soldiers trapped behind the swale. Lee tried to goad Burnside into another attack, but the Union commander balked, so the Confederates simply fortified their position further. December 15 would pass much the same way, and when December 15 waned into December 16, Burnside withdrew his army under the cover of darkness.

Lee, who was usually aggressive, knew this was one victory he could not follow up. He understood that if he counterattacked across the same fields the Union army had just crossed, he would have the tables turned against him. The Federals had 147 cannon placed across the river on Chatham and Stafford Heights, and a large number of Union infantry had not yet been engaged. Frustrated, Lee could only watch the Federal army slip away to safety.

On the night of December 13-14, the Northern Lights had appeared—a rare occurrence that far south. They shone overhead for more than an hour. Union soldiers saw the lights as God’s way of commemorating the brave sacrifice of their fallen comrades. Confederates, on the other hand, said that “the heavens were hanging out banners and streamers and setting off fireworks in honor of our victory.”

But the Battle of Fredericksburg was no magnificent victory for the Confederates, and Lee knew it. At one point, he had watched from a hilltop as the spectacle unfolded below him and had said, “It is a good thing war is so terrible; we should grow too fond of it.” Lee knew what an awful price Burnside’s army had paid in defeat.

The Army of the Potomac had suffered nearly 13,000 casualties, with around 8,000 of them on the ground in front of the stone wall. The Confederates, by comparison, suffered fewer than 5,000 casualties, most of them at the far end of the field near Prospect Hill where Meade achieved his breakthrough.

Those lopsided numbers might suggest a terrible blunder on the part of Ambrose Burnside. However, while his generalship would ultimately prove to be unspectacular, at Fredericksburg Burnside was as much a victim of circumstances, sloppy communication, and poor generalship by his subordinates as he was a victim of his own mediocrity.

Burnside had come to Fredericksburg with many reasons to think he could find victory there.

Instead what he found was, as Lee said, war so terrible.