“People like to cling to their legends and myths,” historian Barry Clifford writes in his 2002 book The Lost Fleet. “‘History,’ someone once said, ‘is written by the winners’; I have found that much of it has also been written by Hollywood.” Although Clifford’s book relates the golden age of piracy, his words can also apply to the legend-making days of the Earp brothers in Tombstone, Arizona Territory. Consider the words, “Boys, throw up your hands—I want your guns,” spoken on the afternoon of October 26, 1881, just prior to the legendary “Gunfight at the O.K. Corral.” That dramatic, now-famous challenge was uttered not by Wyatt Earp, the subject of so many Hollywood movies and a popular 1950s TV Western. In fact, Wyatt wasn’t even in charge that day; he was merely an assistant policeman.

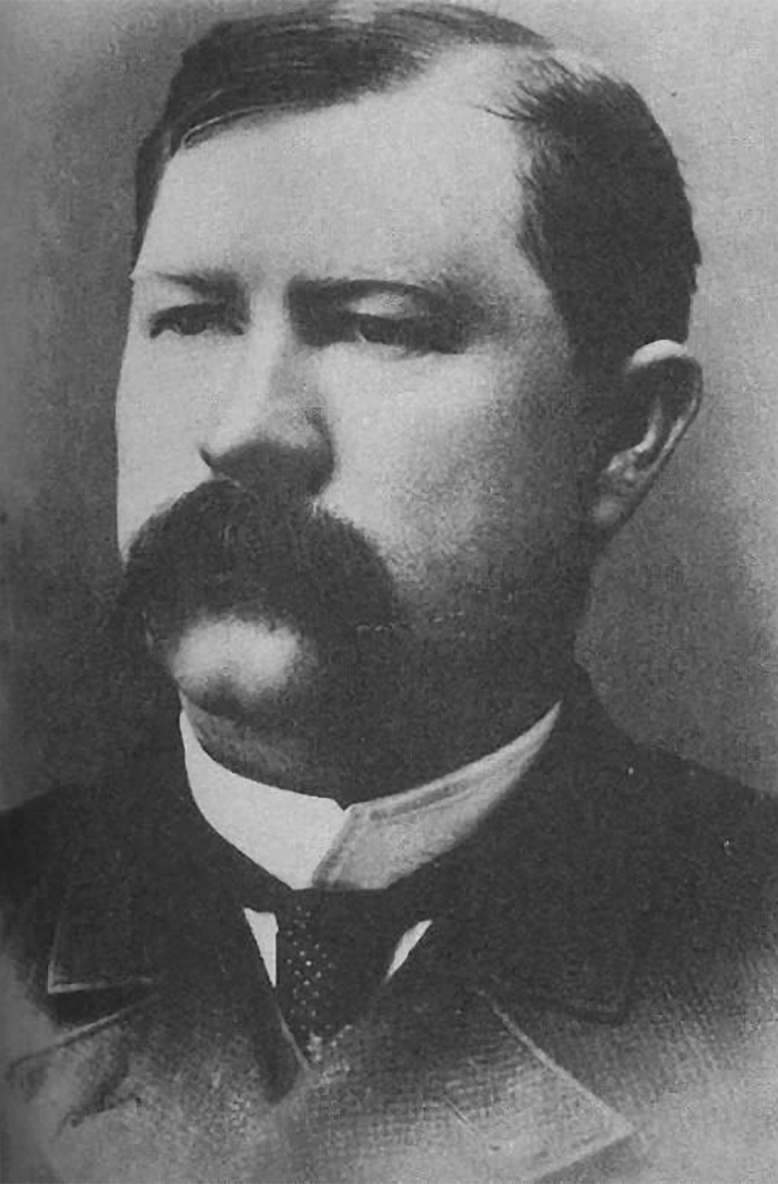

Wyatt’s older brother Virgil was the one who uttered those words, in a vain attempt to avoid gunplay. That’s only fitting, as he was the top lawman, wearing two badges—those of chief of police and deputy U.S. marshal. But that fact has never seemed to register with filmmakers or others who spin tales of the Wild West. In accounts of the Tombstone fight, Virgil inevitably plays second fiddle at best and more often third fiddle behind Wyatt and Wyatt’s pal Doc Holliday. Unlike many Old West badge wearers, Virgil did merit mention in the history books, displaying some of the best characteristics of frontier folk—heartiness, reliability, dutifulness, loyalty, humility, self-reliance, virtue and fortitude. He was a good lawman and a good man, a survivor. Yet Virgil failed to achieve legendary status in his lifetime or since. He will forever live in the shadow of brother Wyatt.

There were six Earp brothers in all. Half brother Newton was the oldest, followed by full brothers James, Virgil, Wyatt, Morgan and Warren. Newton had little interaction with his half brothers. While James preferred gambling, bartending and managing prostitutes to wearing a lawman’s star, he and his four full brothers kept up on each other’s gambling and lawman activities wherever their wanderlust took them.

Virgil Walter Earp, born in Hartford, Ohio County, Kentucky, on July 18, 1843, reportedly spent his teen years farming with the family. On July 26, 1862, according to biographer Don Chaput, Virgil enlisted at Monmouth, Ill., in the 83rd Regiment of the Illinois Volunteer Infantry. Described in service records as “age 19, 5’10” tall, with light hair, blue eyes and light complexion,” he participated in several Civil War skirmishes and in 1863 was listed as “manning siege guns and batteries.” Virgil was mustered out of the Union Army in Nashville on June 24, 1865. He was never wounded in action, and it is unknown whether he killed anyone in combat.

During the decade after the Civil War, Virgil meandered about the West, sometimes with other Earps. He drove stages in California; graded Union Pacific Railroad beds with Wyatt in Wyoming; ran a grocery in Lamar, Mo., where Wyatt was constable and father Nicholas was justice of the peace; and drove stages in the early 1870s in Iowa, where he met third wife Allie Sullivan (first wife Ellen Rysdam remarried after being told by Ellen’s father that Virgil had died in combat in 1863, while his second wife, 17-year-old Rosella Drago, simply vanished from the records). Allie would stick by Virgil for the rest of his life. Virgil may have served briefly as a policeman with Wyatt in Wichita in 1875 and in Dodge City in 1876 and 1877 (no records exist, but he may have been “field deputized” by brother Wyatt or friend Bat Masterson). In May 1877, Virgil headed for California with father Nicholas, older brother Newton and younger siblings Warren and Adelia.

On July 4, the Earp wagon train reached Prescott, the capital of Arizona Territory and a provisioning center for area mines. Virgil and Newton liked what they saw and stopped, while Nicholas and the rest of the Earp clan went on to settle in San Bernardino, Calif. Virgil found a ranch a few miles east of Prescott and spent the summer as a mail rider. After Newton and wife packed up and returned to Missouri, Virgil and Allie moved to an abandoned sawmill just west of Prescott.

It was in downtown Prescott, on October 16, 1877, that Virgil practically stumbled into instant gunfighter fame. He, U.S. Marshal William W. Standefer and Yavapai County Sheriff Ed Bowers were chatting on a corner when Colonel W.H.H. McCall ran up waving a Texas murder warrant for a man named Wilson. Wilson and pal John Tallos had just taken drunken potshots at a woman’s dog—their bullets passing between her legs—drawn on Constable Frank Murray and were now fleeing Prescott. Standefer and McCall jumped into a buggy, Bowers and Murray mounted up, and Virgil, whom Bowers had hurriedly deputized, took off on foot with his Winchester. At the edge of town, the five-man posse caught up with the two hard cases, who immediately opened fire. Both fell in the return crossfire. Tallos lay dead with at least eight bullet and buckshot wounds, and Wilson died a few days later from a bullet wound to his head. The lawmen credited Virgil with having done the most damage in the fight, making him an instant hero. For the moment, he didn’t have to stand in any man’s shadow.

In the spring and summer of 1878, Virgil again drove stagecoaches in Prescott. One of his frequent passengers was Arizona Territorial Secretary John J. Gosper, who served as acting governor whenever John C. Frémont was out of the territory, which was most of the time. Virgil’s acquaintance with Gosper would loom large in the legend-making days of Tombstone. To augment his driver’s income, Virgil cranked up the old sawmill at home and sold lumber. But his much-ballyhooed showing in the Wilson-Tallos shooting apparently gave him a hankering to be a lawman.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

On September 3, 1878, he was officially appointed Prescott’s night watchman. The next month, he gave a peaceful demonstration of his sharpshooting eye. “Some good shooting was done at the gallery yesterday,” The Arizona Enterprise reported on October 5, “the best scores being made by Charles Spencer and Mr. Earp, each making 44 out of a possible 45.” In the November election, Virgil beat out incumbent Frank Murray to win one of Prescott’s two constable slots, a position he held until leaving for Tombstone in November 1879.

While in Prescott, Virgil apparently didn’t engage in any more shooting affrays. As constable he had his hands full with more mundane civil duties. Most of his law enforcement dealings were with U.S. Marshal Crawley P. Dake, who had been appointed to replace Standefer on June 12, 1878. Due to their close association, it was only natural that when Virgil resigned as constable and headed for the Tombstone silver boom, Dake appointed him deputy U.S. marshal for the Tombstone area. Virgil’s extant commission as a deputy U.S. marshal, dated November 27, 1879, proves he was the Earp brother who went to Tombstone as a federal lawman, despite those who insist Wyatt was the one appointed deputy U.S. marshal there.

On the road to Tombstone, a stagecoach roared past Virgil’s wagon, scraping against it and injuring one of his horses. According to an account of the incident, when the deputy marshal caught up to the stage at the next station, he “thumped the puddin’” out of the driver. Virgil was a man of strong character who did not tolerate bad behavior in others. This trait would become evident in the bustling boomtown, where, according to most sources, he, Wyatt, James and their wives arrived in December 1879 and immediately engaged in mining and gambling ventures. “The Earp boys spent thousands of hours in saloons, yet there was never any indication that Virgil or Wyatt loved the bottle,” writes Chaput in Virgil Earp: Western Peace Officer. “They thrived on the atmosphere, enjoyed the talk and were both inveterate gamblers.”

Surrounding Tombstone was a no-man’sland crawling with rustlers, stage robbers and renegade Chiricahua Apaches. The village marshal and the Pima County sheriff handled most law enforcement issues, but they called on Earp when border problems arose, U.S. mail coaches were robbed or long-ranging posses were required.

On October 27, 1880, hard-drinking gunman Curly Bill Brocius shot Marshal Fred White, and when White died the following day, town leaders appointed Virgil temporary assistant marshal. But less than two weeks later, in the special election for marshal, Virgil lost out to Ben Sippy. Within days he resigned as assistant marshal. Voters re-elected Sippy to the top post the following year.

On January 14, 1881, gambler John O’Rourke (aka Johnny-Behind-the-Deuce) shot and killed popular mining engineer Philip Schneider in nearby Charleston and fled to Tombstone just ahead of an angry mob. The January 17 Tombstone Epitaph listed Deputy U.S. Marshal Virgil Earp, Pima County Deputy Sheriff Johnny Behan and City Marshal Ben Sippy as the trio of lawmen who “rescued” the Deuce and hauled him off to Tucson. Legend has it Wyatt Earp lent a hand, which is possible; perhaps the Epitaph mentioned only the lawmen involved, and Wyatt wasn’t a lawman at the time.

Another notable incident occurred on March 15, when outlaws killed the driver and a passenger while attempting to rob the Benson stage. Virgil, leading a posse that included brothers Wyatt and Morgan as well as Bat Masterson, caught one robber and turned him over to crooked Cochise County Sheriff Johnny Behan. The prisoner soon “escaped” from Behan’s custody.

On June 6, 1881, the city council granted Ben Sippy a two-week leave of absence and appointed Virgil temporary chief of police. (When Tombstone became a “city” in February 1881, the marshal’s office became the police department, and the marshal the chief of police.) But Sippy had skipped town for good, so on June 28, the council formally appointed Virgil chief of police. He took the oath of office on the Fourth of July. Virgil was now Tombstone’s top law officer.

His mettle was quickly tested. On June 22, a fire had destroyed more than 60 buildings on the east end of town. Due to past controversy over titles to the now-charred land, lot jumpers put up tents and claimed ownership by right of possession. Virgil, doing double duty as deputy U.S. marshal and chief of police, swore in 23 men as special policemen and swept the lots clear of the jumpers and their makeshift tents. “Mr. Earp is well known as one of the most efficient officers the city has ever had…being fearless and impartial in the discharge of his duty,” the Epitaph reported. On June 28, the paper added: “On Wednesday last, his force kept perfect order and protected life and property in a manner that deserves the highest praise….After the fire, the next day when jumpers appeared on the burned district, Mr. Earp solved the whole problem by reinstating the owners to their possessions and compelling all to respect each other’s rights.” The July issue of Arizona Quarterly Illustrated suggested, “This action of Marshal Earp cannot be too highly praised, for in all probability, it saved much bad blood and possible bloodshed.” Virgil Earp was proving a lawman equal to most any challenge.

Chief Earp upheld the law well over the next several months; the police blotters record many arrests for minor crimes but no major ones. The by-the-book lawman once even arrested Mayor John Clum for riding at “breakneck speed” on the streets of Tombstone. Meanwhile, rustling in the surrounding grasslands had gotten completely out of hand. As Chaput explains it: “Tombstone may have been under control, but Cochise County was not. Although Virgil, as a deputy U.S. marshal, did have authority in Cochise County, his duties as city marshal kept him in Tombstone most of the time. Furthermore, Cochise County had a sheriff and deputies, who were supposedly enforcing the laws. They were not doing so, in part because of the size of Cochise County, in part because the county was newly established and, therefore, inexperienced in the ways of government, and in part because the sheriff was Johnny Behan, a friend, cohort and partner of the very cowboys who were causing the problems.”

In June and July 1881, rustling, gun battles, intervention of the Mexican army and overall bitterness were the order of the day along the border between Cochise County and the Mexican state of Sonora. The Cowboy (rustler) faction, which included the Clantons and the McLaurys, was behind most of the trouble. As the Earp brothers represented the only real law in southeastern Arizona Territory, the Cowboys wanted them out of the way. The showdown, as almost everyone on both sides of the Mississippi now knows, occurred in a vacant lot behind the O.K. Corral on October 26. Billy Clanton and Frank McLaury openly wore holstered six-shooters in violation of a city ordinance. As chief of police, Virgil had no choice but to disarm them. When he and “special policemen” Wyatt and Morgan Earp and Doc Holliday confronted Billy, Frank, Ike Clanton and Tom McLaury, Virgil uttered his oft-quoted command, “Boys, throw up your hands—I want your guns.” Ike ran away as all hell broke loose. When the 30 seconds of gunfire was over, both McLaury brothers and Billy Clanton were dead or dying. Virgil was shot through the left leg, Morgan through the shoulders, and Doc Holliday was grazed on the hip. Wyatt got through the gunfight unscathed, a fact that no doubt bolstered his reputation and obscured the fact he was not the “frontier marshal” that day.

On October 29, citing the gunfight, the city council suspended Virgil as chief of police. Two days later, Justice of the Peace Wells Spicer launched a preliminary hearing to determine whether the lawmen should face murder charges. He ruled that the Earps and Holliday had been enforcing the law and thus would not be indicted. U.S. Marshal Dake even praised Virgil’s actions in the gunfight. But Cowboy vengeance was as cowardly as it was bloody. On the night of December 28, shotgun-wielding assailants ambushed Virgil on Allen Street, crippling his left arm and very nearly killing him. As doctors examined his wounds, he weakly told Allie, “Never mind, I’ve got one arm left to hug you with.” His recovery was slow. Eventually, he was able to walk around the house and then outdoors, but, as Chaput writes, “Virgil Earp had little to do with subsequent events in Tombstone.”

On the night of March 18, 1882, the Cowboys ambushed another Earp, shooting Morgan in the back through a window while he was playing pool at Hatch’s Saloon. Brother Wyatt, who had been appointed a deputy U.S. marshal the day after Virgil was wounded from ambush, now decided to spirit the crippled Virgil out of town to safety. On March 19, the brothers sent Morgan’s body to father Nicholas Earp’s home in Colton, Calif., 60 miles east of Los Angeles, and Virgil followed the next day. Even as Virgil’s train pulled out of Tucson, Wyatt caught Frank Stilwell—one of the Cowboy assassins—lurking around the station. He and Doc Holliday pumped Stilwell full of lead, marking the beginning of Wyatt’s infamous vendetta ride. The vengeance killings further boosted Wyatt’s reputation, leaving Virgil in his trail dust.

Virgil and Allie settled down in Colton. When Virgil traveled to San Francisco for further surgery on his crippled arm, he gave an interview to the Daily Examiner. “Virgil Earp is not a ruffian in appearance,” the newspaper said. “He was found in a sleeping car, smoking a cigar. His face, voice and manner were prepossessing. He is close to six feet in height, of medium build, chestnut hair, sandy mustache, light eyebrows, quiet, blue eyes and frank expression.” Virgil recollected Tombstone in the May 27, 1882, edition: “I was asked to go to Tombstone in my capacity as United States marshal [sic] and went. My brother Wyatt and myself were fairly well treated for a time, but when the desperate characters who were congregated there, and who had been unaccustomed to troublesome molestation by the authorities, learned that we meant business and were determined to stop their rascality if possible, they began to make it warm for us.”

Virgil reveals the Earps’ lifetime ties to Wells, Fargo & Co. near the end of the interview: “‘The stories, at one time widely circulated, that we were in with the Cowboys and quarreled over the division of their spoils was ridiculous. It was at least disbelieved by Wells, Fargo & Co., who I represented, and while I was city marshal, they gave me this.’ The speaker here displayed on the inside of his coat a large gold badge, a five-pointed star set inside of a circular band, inscribed on one side CITY MARSHAL, TOMBSTONE, A.T., and on the other, V.W. EARP, WITH COMPLIMENTS OF WELLS, FARGO & CO. Mr. Earp was in such pain that for the time his story was cut short.”

Neither Virgil’s pain nor his crippled arm seemed to slow him down, though. In August 1882, San Francisco authorities arrested him for operating a faro game. But back in Colton, he and Allie planted roots. Virgil became active in Republican politics. In the summer of 1886, he opened his own detective agency, and on July 2, he was elected constable, with father Nick sitting as justice of the peace.

As constable, Virgil mostly dealt with drunks and tramps. His sister Adelia recalled an 1887 incident in which a drunk made a disparaging remark about Virgil’s crippled arm: “In about the tick of the clock, [the drunk] was off his feet, right up off the street and onto the sidewalk, and pretty hard up against the wall, spread-eagled. Virgil did all this in one move, with one arm. He sure was a strong feller! He just frisked this young drunk a bit rough and pushed him way, and said, ‘Now, you just run along home, boy.’” Still, Virgil was known for his even temper and would draw his gun only after other approaches had failed. “Virgil had killed a few men in his duties as a peace officer, in Prescott and in Tombstone, but he solved most disputes with a kind, firm word or a stern warning,” Chaput writes. “If these methods did not produce the desired action, Virgil and Wyatt Earp performed their most efficient law-and-order technique, that of buffaloing, or slamming the barrel of a pistol across the opponent’s forehead. Even one-handed Virgil could still perform that operation with ease.”

On July 11, 1887, Virgil was elected Colton’s marshal. The July 14 issue of the neighboring San Bernardino Daily Times noted: “V.W. Earp, the newly elected city marshal, sports a gold badge that was presented to him by the Wells, Fargo express company for services done at Tombstone, A.T., years ago, when he was marshal of that city. It is a beauty and cost in the neighborhood of $80.” Virgil was re-elected marshal the following April, serving out his term without any deputies to assist him. No crimes of note occurred during his two terms as marshal, and on March 9, 1889, he resigned the post, perhaps out of boredom.

Like brother Wyatt, Virgil promoted and refereed boxing matches and operated a gambling hall. He abruptly moved to the coastal town of San Luis Obispo to follow the horseracing circuit, but soon returned to the Colton/San Bernardino area. Then, in 1893, Virgil again got the mining bug. Two years earlier, prospectors had struck gold about 150 miles northeast of San Bernardino, giving rise to the boomtown of Vanderbilt. In April 1893, Virgil showed up with an array of gambling equipment and built Earp’s Hall, Vanderbilt’s only two-story building. Hosting everything from gambling and boxing matches to dances and church services, Earp’s Hall became the most popular place in town; only trouble was, the boom was short-lived. The Republican Virgil ran for constable in the largely Democratic town and lost. So, in late 1894, Virgil sold the hall, and he and Allie moved back to Colton.

Another mining boom drew Virgil and Wyatt and their wives to Cripple Creek, Colo., in the summer of 1895. The Earps wanted to open a saloon and gambling hall but had arrived too late to compete with the established saloons. In October, Virgil and Allie returned to Prescott, where Virgil invested in the “Grizzly” Mine.

Grizzly it turned out to be. On November 17, 1896, a tunnel caved in on Virgil. As Chaput relates it: “Virgil was knocked unconscious for several hours. . . . [His] hip was dislocated, his feet and ankles were badly crushed, his head severely cut, and the rest of his body was a collection of serious bruises. Virgil’s life was in peril, but this did not end his mining career.” Two months later, the January 23, 1897, Journal-Miner reported: “Mr. Earp has had two or three experiences in his life which very few men would have lived through, this being one of them. He has been shot all to pieces and crushed in this mine accident, but still has hopes, as well as good prospects, of living to a ripe old age.”

Most men would have retired to a rocking chair. Not Virgil. He spent the rest of the decade working a small cattle ranch, tempting fate in the Grizzly again, and serving as a special officer or deputy for the courts and various law enforcement agencies. In the fall of 1898, he received one of the biggest shocks of his life in a letter from a woman in Portland, Ore., named Jane Law. Turns out, Law was the daughter born to Virgil and first wife Ellen Rysdam in July 1862, just before he left to fight in the Civil War. In early 1899, Virgil and Allie went to Portland to meet his adult daughter for the first time, and for weeks the local newspapers reported on the unusual reunion.

In 1900 Virgil re-entered politics as the Republican nominee for sheriff of Yavapai County, but for unknown reasons he declined to run. Later that year, he made an uncharacteristically pretentious speech about his colorful life, a life that required no embellishment. On July 6, a gunman shot down Warren Earp during a saloon dispute in Willcox, Arizona Territory. Stories abound to this day that either Virgil alone or Virgil and Wyatt together secretly traveled to Willcox and avenged the death of their brother. But recent books like Michael Hickey’s The Death of Warren Baxter Earp have proved they didn’t.

For the next few years, Virgil and Allie bounced back and forth between Colton and Prescott. Then in 1902–03, Virgil sold off his Prescott properties. In 1903 he caught wind of another gold strike, this time at Goldfield in southern Nevada. Virgil resisted the lure of riches for several months, but he and Allie ultimately settled there in the summer of 1904. On January 26, 1905, Virgil took the oath as a deputy sheriff of Esmeralda County. It would be his last position as a lawman.

Virgil reportedly never got in any scrapes as Esmeralda’s deputy. As Chaput writes: “He became very sick with pneumonia, recovered and had several relapses….He was bedridden much of the time. When he was at his post at the National Club, though, it is unlikely that anyone pestered him, or that he was unable to dispense his version of law and order. He was still a large man and, although one-armed, capable of drawing a pistol and buffaloing the malcontent.”

Virgil the vigilant had overcome much and handled adversity well. But even the hardiest survivor must call it a day at some point. Virgil died in relative obscurity of contagious pneumonia on October 19, 1905. “Virgil by this time was less widely known than younger brother Wyatt, and his obituaries were pretty much limited to newspapers in Arizona and Nevada,” writes Chaput. In one final twist of fate, instead of burying Virgil in southern California, Allie sent his body to his daughter Jane in Portland. There he lies, buried on a grassy knoll at Riverview Cemetery, forgotten by all but a few dedicated Earp historians.

Why did the name Virgil Earp fade into obscurity, while the name of his younger brother Wyatt ascended the peak of Old West legend? There are many possible explanations, but two make the most sense.

First, although Virgil wore the badge of authority in tumultuous Tombstone on that fateful day in October 1881, Wyatt was the only one who weathered the shootout near the O.K. Corral without being wounded or killed or running away. That fact sparked the Wyatt Earp mystique, one that gathered momentum in the following decades, transforming him into something of an invincible superhero.

Second, Virgil, badly wounded in the subsequent ambush, went to California to recuperate and dropped from the Tombstone picture for good. Wyatt, on the other hand, prompted increasingly sensational newspaper headlines during his vendetta against the men who had crippled Virgil and killed Morgan. And so Virgil’s name has always been associated with legend, but it has never become legend.

While Virgil rests in his obscure Portland grave, Wyatt’s grave, some 500 miles south at Hills of Eternity Cemetery in Colma, Calif., attracts thousands of tourists each year. It might now be said the permanent shadow Wyatt casts over his brother extends 500 miles and across three centuries.

Lee A. Silva is author of the multivolume Wyatt Earp: Biography of the Legend. Volume I: The Cowtown Years and Volume II, Part I: Tombstone Before the Earps are suggested for further reading, as is Don Chaput’s Virgil Earp: Western Peace Officer.