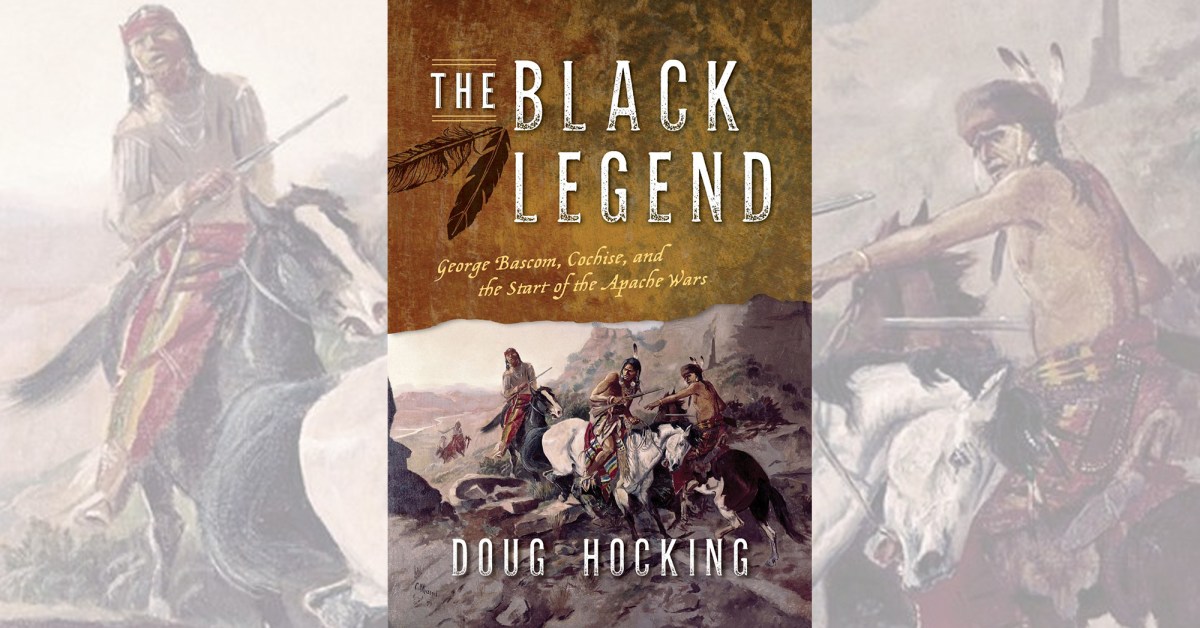

The Black Legend: George Bascom, Cochise and the Start of the Apache Wars, by Doug Hocking, TwoDot, Guilford, Conn., 2018, $24.95

In an odd semi-parallel to Billy Joel’s 1973 song “The Ballad of Billy the Kid,” Doug Hocking came from Long Island to settle in New Mexico and Arizona, where he came to know the resident Anglos, Mexicans and Indians as both present-day friends and in the context of history, ethnography and archaeology. This, plus access to many of the sites where historical events occurred, led him to research one of the pivotal episodes in Arizona history—the February 1861 attempt by Lieutenant George N. Bascom to recover a kidnapped child from the Apaches, which led to a succession of misunderstandings that ended up touching off 11 years of war between the U.S. military and Chiricahua Apaches under Cochise.

For more than a century and a half after the Bascom Affair, historians have invariably laid blame primarily on its namesake’s shoulders for having sparked the war. To summarize, when Cochise denied his people had kidnapped Felix Ward and then asked for 10 days to find him and arrange for his return, Bascom tried to detain the Apache chieftain, who managed to escape nonetheless, sparking a standoff that resulted in the killing of white hostages, the hanging of Apache hostages and ultimately all-out war. Since then, that story has become entrenched through repetition by one writer after another. Hocking, however, claims his in-depth research on the subject reveals Bascom was not the prime mover of those unfortunate events and, instead, has been a classic victim of decades of snowballing errors.

In The Black Legend Hocking takes a systematic look into the tensions in Arizona Territory in 1861 and the realities that motivated Cochise’s leadership of the Chokonen band of the Chiricahuas. He reveals a pragmatist whose actions sometimes contradict the “noble savage” image some whites wished to bestow on him. He also presents a series of eyewitness accounts that contradict long-accepted assumptions regarding Bascom’s intentions and even how much authority he had to carry them out. As Hocking reconstructs the events, some readers might be put off by his tendency to repeat key points, as if he were the defense attorney at a court-martial, periodically reminding the tribunal of the germane evidence and testimony. As for the accounts on which posterity’s condemnation of Bascom are based, Hocking reveals at least two to be patent falsehoods from individuals who had probably not even been present at the respective events. His conclusion (spoiler alert): “Every element of the popular legend is false. Most of it was the invention of a self-serving, self-promoting soldier who saw the opportunity to make himself a hero at Bascom’s expense.” For anyone who needs convincing, however, there is plenty of material in the 10 appendices from which one can draw one’s own conclusions.

—Jon Guttman