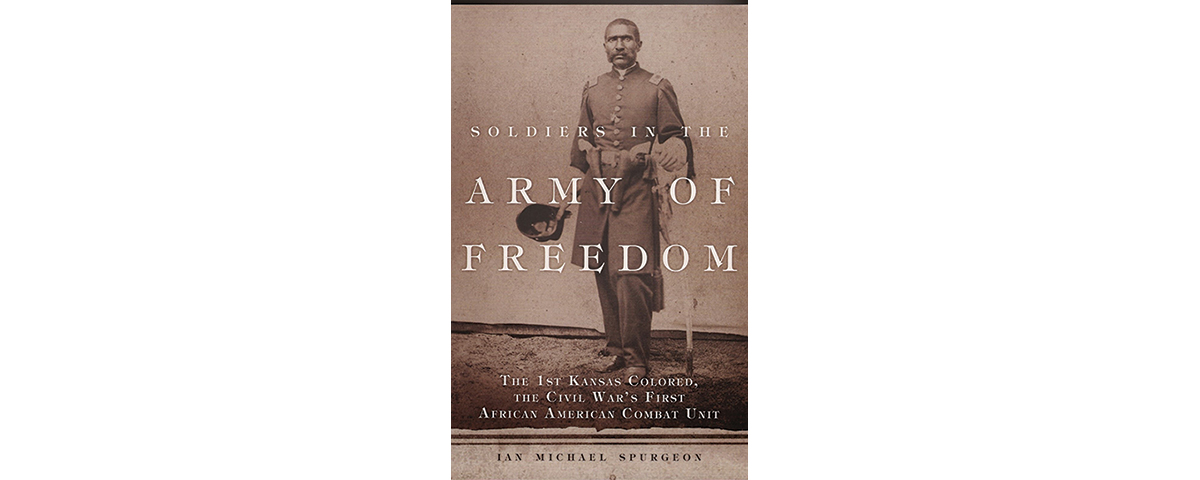

Soldiers in the Army of Freedom: The 1st Kansas Colored, the Civil War’s First African American Combat Unit, by Ian Michael Spurgeon, Vol. 47 in the Campaigns and Commanders series, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2014, $29.95

Some 15 years after the release of Edward Zwick’s film Glory, Ian Spurgeon, historian for the World War II division of the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, has published a history of the first black regiment to fight in the Union Army—the 1st Kansas Volunteer Infantry (Colored). One question someone unfamiliar with Civil War history might ask is how such a unit could possibly have formed in Kansas, which in 1860 claimed only 627 black residents—about six-tenths of a percent of the territory’s population? To answer that, the author devotes the first two chapters of his book to Kansas’ prewar political life. In those years the hotly contested slavery issue had already thrown the territory into a state of virtual civil war. It was U.S. Sen. James Henry Lane of Kansas who stretched his authority to organize the 1st Colored Infantry in 1862, though the principal reservoir of recruits turned out to be neighboring Missouri, whose black population exceeded 11,000.

On Oct. 29, 1862, a 250-man detachment of the 1st Kansas Colored drove off Confederate forces at Island Mound, Mo., the first time black Americans defeated Southern whites on the battlefield. The author goes on to study the regiment’s subsequent battles, from its victory at Honey Springs on July 17, 1863, to its disastrous defeat at Poison Springs on April 18, 1864. In the latter engagement Spurgeon estimates the original force of 463 men sustained 182 casualties—an appalling 39 percent, one of the highest combat casualty rates among all Union regiments. One reason for such losses was the obsolete equipment issued to the regiment. Its troops carried secondhand Austrian muskets that were slow to reload, rendering the soldiers stationary targets for opposing white, Choctaw or Cherokee Confederates, who were equipped with modern carbines and revolvers. Another reason was that Confederates didn’t take black prisoners, while Choctaws and Cherokees often scalped their enemies for good measure.

On Oct. 1, 1865, when the War Department officially mustered out the 1st Kansas Colored from federal service at Pine Bluff, Ark., its roster listed 23 officers, 97 noncoms and 401 soldiers. The vast majority of the black troops did not return to the territories from which they had come, and the author describes each member’s particulars in a full catalog of the unit’s six companies. Spurgeon has added an excellent volume to the growing canon of unit histories whose historic importance goes beyond America’s Civil War.

—Thomas Zacharis