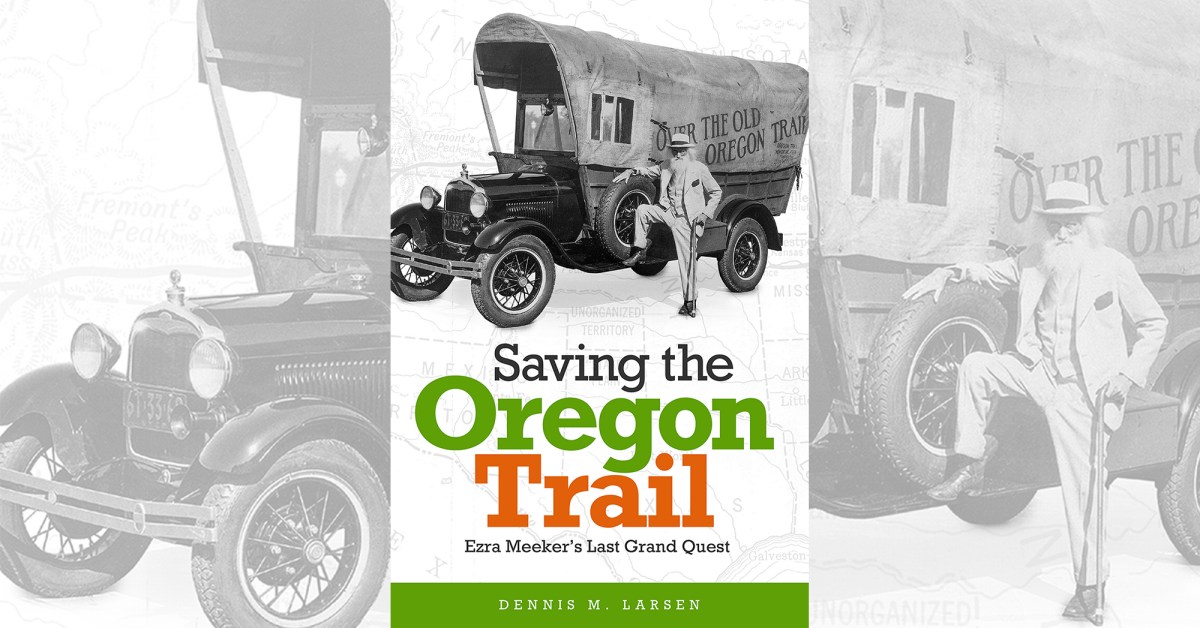

Saving the Oregon Trail: Ezra Meeker’s Last Grand Quest, by Dennis M. Larsen, Washington State University Press, Pullman, 2020, $28.95

Wild West presented the Ezra Meeker story in brief in special contributor John Koster’s August 2020 feature “Nothing Meek About Him.” The pioneer is remembered for having traveled the Oregon Trail in his 20s in 1852, then raised awareness of the neglected route by traversing it again by ox and wagon at age 75 in 1906. But, of course, there is so much more to learn about the fascinating and magnificently mobile Meeker, who died within a month of his 98th birthday. For that look no further than Dennis Larsen, a retired high school history teacher and leading expert on Meeker. Saving the Oregon Trail is his concluding volume on Meeker. Earlier came The Missing Chapters: The Untold Story of Ezra Meeker’s Old Oregon Trail Monument Expedition (2006), Slick as a Mitten: Ezra Meeker’s Klondike Enterprise (2009) and Hop King: Ezra Meeker’s Boom Years (2016).

Meeker never forgot the storied emigrant trail, whose heyday came before completion of the first transcontinental railroad in 1869. He wrote about traveling the Oregon to become one of Washington Territory’s first pioneers and kept on writing, promoting and preserving throughout his long life. “Ezra Meeker bestrides the legacy of the Oregon Trail like a colossus,” historian Will Bagley writes in the foreword. Meeker was the main man behind the Oregon Trail Memorial Association, incorporated in 1926. The Ohio native shouldn’t be forgotten for his role as the greatest defender of that trail, but he was many other things as well, including the “Hop King of the World” in the late 1870s–80s, a Klondike adventurer (after having gone bankrupt in the 1890s), president of the Washington State Historical Society, a women’s suffrage advocate and author of a book The Tragedy of Leschi, about the wrongful hanging of a Nisqually chief. “Ezra Meeker’s ethical humanity,” writes Bagley, discredits one of the worst excuses for past prejudices—the argument that bigotry was the societal standard of the time, so everybody was doing it. Not everybody: His ethical core condemned prejudice.”

Meeker was both a dreamer and a doer. He was a hard worker, risk-taker, self-promoter and ruthless competitor who, Larsen writes, had “a vision of the future that was unerringly accurate,” but who also had a pugnacious side that “tended toward self-righteousness [and] grated on many.” As Larsen details in these action-packed 266 pages, the driven and complex Meeker “could live as easily in a log cabin or a covered wagon as in a mansion.” The author delivers the good and bad about the man, mentioning how Meeker’s single-mindedness and crusading spirit could alienate people and took a toll on family and friends. But largely thanks to him, monuments and interpretive centers dot the route of the Oregon Trail, which he covered multiple times. He was also an early proponent of a transcontinental highway as a national defense measure. In 1928 Meeker was touring New England in his “Oxmobile,” supplied by Henry Ford. It was, according to The New York Times, “to be a preliminary to Mr. Meeker’s sixth transcontinental trip over the Oregon Trail.” Grave illness disrupted his plans, and the end of his long trail neared. His funeral was held in Seattle. Fittingly, a pair of oxen pulled a prairie schooner filled with flowers to the mortuary.

—Editor

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.