“Deep Throat” was hiding in a dark parking garage when he directed Washington Post reporter Bob Woodward to “Follow the money” to unravel the Watergate scandal, but David Thomson is not being so subtle. In his new book, Bonds of War: How Civil War Financial Agents Sold the World on the Union, he’s imploring Civil War enthusiasts and historians to explore the financial aspects of the conflict to better understand it. For readers familiar with a Civil War vocabulary that includes generals, regiments, battles, and campaigns, Thomson suggests they add Jay Cooke, demand notes, 10-40 and 7-30 bond issues, specie payments, balance sheets, and greenbacks to their historiographic lexicon. Those who do will be treated to a fascinating foray into the world of Civil War finance and the beginnings of modern America’s financial markets.

Wars are expensive. By the time of the Civil War, Thomson reminds us, “the United States joined the long list of nations opting for bond issues to finance its conflicts.” The country’s previous conflicts had been financed that way with the cooperation of financial elites residing, to a large extent, on Wall Street and Northern banking houses. But the Civil War quickly grew far larger than anyone had expected and, as Thomson points out, “Union officials recognized that the support of northeastern elites would not be enough to keep the Union war machine alive.”

Where to turn for the money? Thomson details a triumvirate of financial instruments: a variety of bond issues, greenbacks (the first nationally recognized currency other than gold or silver), and the first federal income tax. “None proved more critical,” Thomson concludes, “than the various bonds and Treasury notes issued by the federal government during the war.” These bond “provided nearly two-thirds of the $3.2 billion in funding for the Union cause—and in doing so helped keep the country afloat financially.”

The hero of that story is not Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase although he was successful in negotiating the initial $50 million loan, principally from New York banks, at the war’s outset. That money, however, was soon exhausted. Foreign investors were understandably hesitant to commit funds to the Lincoln government, especially when Union armies were experiencing defeat on the battlefield. Chase did believe that “a popular loan could take flight if given enough support and pitched properly.” He believed, wrongly, that he could do it himself. But when sales turned flat, Jay Cooke entered the picture with new ideas and the history of American finance entered a new, more modern phase.

Bonds of war

How Civil War Financial Agents Sold the World on the Union

By David K. Thomson

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.

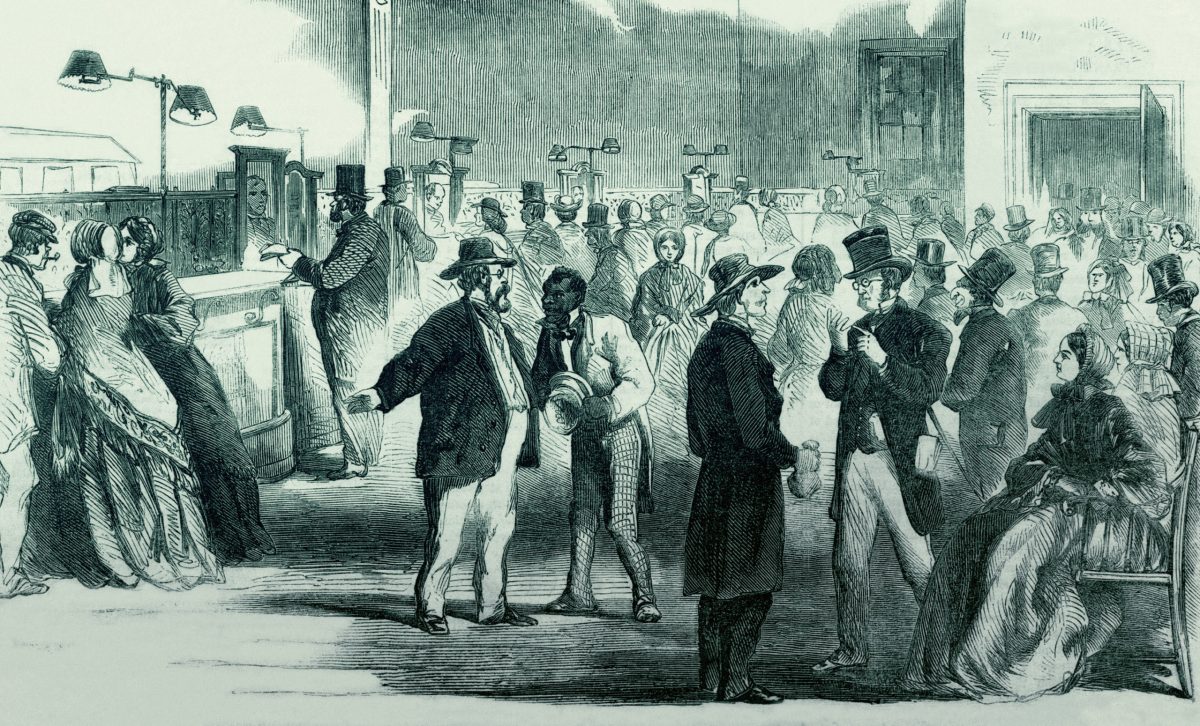

In 1861, Jay Cooke was a partner in a newly formed financial house in Philadelphia. He and his brothers saw the war as a great financial opportunity. “By the fall of 1861,” Thomson informs us, “Cooke endeared himself enough to Chase to be granted an agency to try to sell Northern bonds on behalf of the government.” Cooke’s modern marketing ideas exuded confidence in the Union cause and helped him succeed beyond anyone’s expectations. Early on, he advertised in local newspapers and published the names of his small subscribers, using the power of patriotism to motivate others. He sent his agents door-to-door all over the country. Cooke kept his offices open late so working people could purchase notes as small as $20; he set up payroll deduction schemes to make purchases easier for employees of large firms like the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad. Thomson concludes that more than anything else, “Cooke and his army pitched investing as a form of patriotism.”

Thomson credits Cooke with making the war a people’s war by understanding that what mattered most to people was confidence—confidence that he and his itinerant legion of salesmen preached like evangelists “spreading the gospel of capitalism and Union” across the nation and abroad. Confidence, Thomson concludes, “became sort of an emotional commodity, ultimately providing a more durable basis for the Civil War economy than the antebellum one of cotton and the enslaved.” By buying into the Union cause, Americans were buying into themselves.