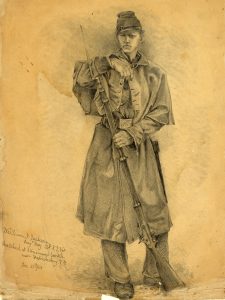

From the beginning the Civil War created a demand for hospitals that neither the North nor the South could meet. Even before seeing combat, newly enlisted men often contracted contagious diseases in camp. Once fighting occurred, the wounded would strain already sparse health care resources: limited doctors and ambulances; untrained nurses; lack of medical supplies; not even appropriate places for the afflicted to lay their heads while recovering. Temporary hospital spaces were usually needed after battles, so medical departments resorted to using hotels, barns, farmhouses, tobacco warehouses, even the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol.

As the war went on, it became clear that more permanent hospital spaces were essential, and the surgeons general for both governments soon determined that the pavilion-style hospital blueprint—already in use throughout Europe, especially France and England—was the best. This design featured long narrow wards or units that incorporated multiple windows located in opposing pairs for cross-ventilation. Additional features addressed other types of supplemental ventilation; specified heat sources; bed placement and square-foot requirements for windows to take advantage of sunlight; cubic foot requirements per patient (ideally 800–1,200 cubic feet instead of the earlier accepted 500–600 cubic feet); nonporous building materials; building length-to-width ratios; placement of doors; location of support rooms; and number of stories.

The location of the sewers was also crucial (for more, see www.civilwarmed.org/sewers). Water, preferably both hot and cold, was needed for drinking, bathing, and wound care, but it was also vital for collecting and disposing of bodily wastes. Dr. William Hammond, then surgeon general of the Union Army, set forth the basic principles of sanitation in 1863. He recommended one bathtub for every 26 patients, one water-closet (or toilet) for every 10, and one wash basin for every 10. Ventilation of the toilet area was deemed vital, and, if water was available, it was to be used to carry off fecal material immediately.

Many hospitals came close to or fully achieved these ideal suggested conditions. In some cases, however, the water supply was insufficient to permit continuous flow through the toilets, so they were only flushed every few hours or so. Similarly, some hospitals collected waste in outdoor pits or boxes that had to be emptied periodically. Great care was taken to ventilate the water-closets adequately.

Death rates were much lower in some hospitals than in others, but the reasons why were not always obvious. The famed Florence Nightingale led an augmented research effort into that by studying the design and survivability of hospitals used during the Crimean War. She later widened her study to include other European hospitals, and even included statistics in her findings.

Nightingale was among those to conclude that the pavilion design typically offered the best outcomes for patients. Improved ventilation was a particularly important factor, as were sanitation and the prevention of the spread of disease.

In an age many consider to be medically archaic, professionals and epidemiologists were making connections between good ventilation, cleanliness, and health (for an example, see Dr. Hammond’s 1863 A Treatise on Hygiene). Today, the connection of greater cleanliness and ventilation to better health seems obvious, but in the Civil War era the discovery was significant.

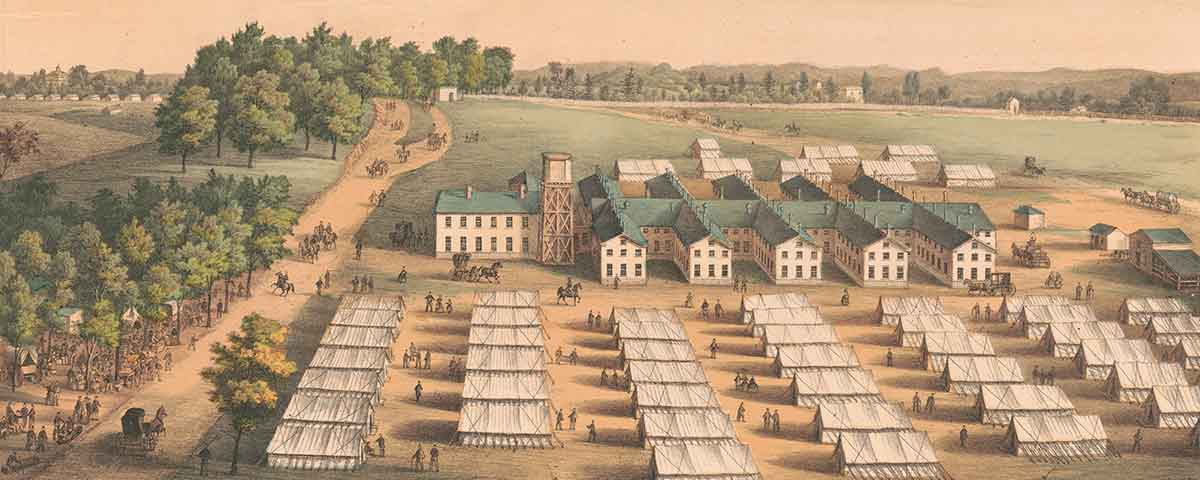

The first pavilion-style hospital constructed during the war was Chimborazo in Richmond. Built in October 1861, it included 150 pavilions and 4,000 beds. It would remain the South’s largest hospital during the war.

In the North, West Philadelphia U.S. General Hospital (better known as Satterlee) opened in June 1862—a pet project of Hammond’s. It had 36 pavilions containing more than 3,500 beds, and 150 other tents were placed around the buildings in event of an emergency or nearby engagement. Several other pavilion-style hospitals of comparable size quickly followed above the Mason-Dixon Line.

Due to the rapid increase in the number of sick and wounded, many pavilion hospitals were “fast-tracked.” Satterlee had been quickly built, and various flaws were discovered as the war progressed, which fortunately led to improvements for future construction projects.

Some pavilion hospitals were not constructed from the ground up. Instead, existing structures were converted to the pavilion style. Campbell Hospital in Washington, D.C., for example, had been built and used as a cavalry barracks. As such, it too was plagued by design flaws when it opened in September 1862 with 11 pavilions and 900 beds.

The pavilion design would continue to be used throughout the Civil War, especially by the Union, and it became the premier hospital design, both military and civilian, in the decades following the conflict. Today, though, the design is considered obsolete and outdated. Most hospitals now favor private patient rooms, yet many of the design innovations, such as good ventilation and lighting, are still considered important.

William T. Campbell, Ed.D., RN, is an associate professor of nursing at Salisbury (Md.) University. He has been a student of the Civil War for more than 50 years, his interest first sparked as a youth in southern Delaware thanks to frequent trips with his aunt to Civil War battlefields. This blog first appeared in the National Museum of Civil War Medicine’s blog on February 20, 2018.