Months after contracting the Spanish flu, Woodrow Wilson suffered a massive stroke, leaving his wife and doctor to run the country

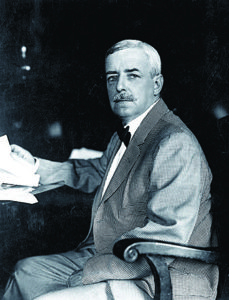

AT 11 A.M. ON MONDAY, October 6, 1919, a grim Secretary of State Robert Lansing gazed across the table at nine men seated in the White House Cabinet Room. The members of President Woodrow Wilson’s cabinet had come, at Lansing’s call, to an unprecedented meeting. Historically, the cabinet did not convene without the president’s approval. However, circumstances demanded action, and no department head had balked. The president’s chair, at the head of the table, remained empty.

Four days earlier, Wilson had “taken ill,” as the newspapers were phrasing it, and since then had been incommunicado. Washington is a rumor factory, and the capital was jittering with dark talk. No one knew if Woodrow Wilson ever again could do the job voters twice had elected him to do. Lansing, who had not seen his boss since early September, suspected the worst about the president’s condition. Lansing thought the cabinet should squarely face a topic that days earlier would have been unthinkable—transferring power from a disabled president.

For the cabinet, Lansing, 54, had two questions: who was to decide if the president was disabled, and, if so, should the cabinet, which so far had done nothing, run the executive branch in Wilson’s absence? Lansing suggested that Vice President Thomas R. Marshall, who was elsewhere in Washington that day, might have to fill the void.

The official cabinet meeting answered neither question. Ending the session but requesting that his fellow secretaries remain, Lansing summoned Dr. Cary T. Grayson, the president’s personal physician. Lansing and colleagues pressed Grayson for details on his patient’s condition. Genially sidestepping, the doctor painted Wilson in rosy tones. The president’s mind was “not only clear but very active,” the doctor declared. All that was afflicting Woodrow Wilson, Grayson claimed, was a touch of indigestion and “a depleted nervous system.”

Lansing, an attorney who had served Wilson through the recent world war and during the peace talks at Versailles, knew when he was being snowed. Grayson, 40, had made Lansing’s antennae vibrate by “carefully avoiding giving any definite information,” Lansing wrote later. However, the secretary of state had no concrete information with which to challenge the medical practitioner, who protested that Lansing lacked authority to call a cabinet meeting without the chief executive’s knowledge.

The awkward two-hour meeting ended in a whimper, with Secretary of War Newton D. Baker assuring Grayson that the cabinet had been meeting innocently to address unfinished business. Baker asked the physician to convey the cabinet’s best wishes to Wilson.

Not knowing Wilson’s condition or prognosis, the cabinet—and the entire nation—spent the next 17 months paddling in a sea of hearsay, whispers, and speculation.

Only Grayson and, more importantly, Edith Bolling Galt Wilson, the president’s second wife, were regularly in the ailing Woodrow Wilson’s company and privy to his true condition, but neither was forthcoming.

For a year and a half, the United States of America operated under an unelected shadow government of two.

Born in Virginia in 1856, Thomas Woodrow Wilson rose to prominence first as president of Princeton University and then as New Jersey’s governor. A Democrat, he wore the cloak of progressive reform when he campaigned for the presidency in 1912, defeating Republican William Howard Taft and Bull-Moose candidate Theodore Roosevelt.

Standing 5’11” at 170 pounds, Wilson, 62, looked statesmanly and fit, but his health was far from robust. He had suffered strokes in 1896 and 1906, and endured bouts with chronic headaches and hypertension.

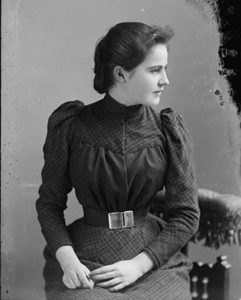

In his first term, Wilson helped create the federal reserve banking system and sent the U.S. Army to chase Mexican outlaw Pancho Villa. His wife, Ellen, died on August 6, 1914, leaving him despondent. Within a year, however, the president fell head over heels for Edith Bolling Galt, a well-to-do 42-year-old widow and the first woman in the capital to drive her own car. A whirlwind courtship ensued, and on December 18, 1915, the couple wed. The two doted on each other for the rest of Wilson’s life.

In August 1914, Europe went to war. Amid debate over whether the United States should join the fight, Wilson firmly advocated that the country be “neutral in fact as well as in name during these days that are to try men’s souls.”

In 1916, running for reelection on the slogan “He kept us out of war,” Wilson narrowly defeated Republican challenger Charles Evans Hughes.

Neutrality became untenable in 1917, as Germany waged unrestricted submarine warfare and sought to egg Mexico on to attack the southwestern United States. On April 2, 1917, the United States declared war on Germany. “Neutrality is no longer feasible or desirable where the peace of the world is involved and the freedom of its peoples…” Wilson told Congress. The nation mobilized and sent two million doughboys and Marines to France to join French and British forces in a final push that defeated the Kaiser.

A November 11, 1918, armistice ended the fighting, but Wilson had a new cause. He envisioned an international body empowered to resolve multinational disputes peacefully. Wilson saw the proposed League of Nations “as the organized moral force of men throughout the world, and that whenever or wherever wrong and aggression are planned or contemplated, this searching light of conscience will be turned upon them…” The vehicle for creating the League, the Treaty of Versailles, faced formidable opposition in the United States, which would join the League only if the Senate ratified the treaty with a two-thirds vote.

Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge (R-Massachusetts) was leading the opposition, whose main objection to the treaty was a provision stipulating that an attack on any League member would, Lodge said, bring a military response from member nations. “I must think of the United States first,” Lodge said, characterizing the League as a threat to American sovereignty that would dilute the express power assigned Congress to declare war. The mutual-aid provision risked “plunging the United States into every controversy and conflict on the face of the globe,” Lodge feared.

Wilson made the League a personal crusade. Despite headaches and high blood pressure, he decided that he would take his case to the people. On September 3, 1919, a determined but weary Wilson embarked on a four-week tour of western states with speeches scheduled in 29 cities. “I know that I am at the end of my tether,” he told Joseph P. Tumulty, his secretary—a position analogous to today’s presidential chief of staff. “Even though, in my condition, it might mean the giving up of my life, I will gladly make the sacrifice to save the treaty.” Train travel was punishing and speeches taxing—in those sketchily electrified days, orators often had only their lungs for amplification.

On Thursday, September 25, Wilson was addressing a crowd in Pueblo, Colorado, when he began having difficulty speaking and maintaining his train of thought. Alarmed, his wife and Grayson persuaded him to cancel his grueling tour and return to Washington. At the White House the following Thursday morning, October 2, Wilson was sitting on the toilet when he tumbled to the floor, striking his head on the bathtub. A blocked cerebral artery had caused a stroke. The clot paralyzed Wilson’s left side, diminished his vision, restricted his speech, and impaired his judgment. The White House staff lifted him into bed. Later that day, to White House usher Ike Hoover the president “looked as if he were dead,” Hoover wrote in a later memoir. “There was not a sign of life.”

On October 3, newspapers reported that Wilson was ill and, while recovering, had to “divorce his mind from his executive duties,” but offered few details. The same day, Lansing braced Tumulty, demanding information. The president’s secretary admitted that Wilson was in bad shape; Tumulty pointed ominously to his own left side, suggesting that Wilson had suffered a paralyzing stroke. Lansing told Tumulty and Grayson that if Wilson was disabled, the president must step aside and hand responsibility to Vice President Marshall. The other two men erupted.

On October 3, newspapers reported that Wilson was ill and, while recovering, had to “divorce his mind from his executive duties,” but offered few details. The same day, Lansing braced Tumulty, demanding information. The president’s secretary admitted that Wilson was in bad shape; Tumulty pointed ominously to his own left side, suggesting that Wilson had suffered a paralyzing stroke. Lansing told Tumulty and Grayson that if Wilson was disabled, the president must step aside and hand responsibility to Vice President Marshall. The other two men erupted.

“You may rest assured that while Woodrow Wilson is lying in the White House on the broad of his back,” Tumulty roared, “I will not be a party to ousting him!” Tumulty and Grayson vowed to deny that the president was disabled. Lansing called a cabinet meeting for October 6.

Edith Wilson raised the topic of her husband resigning with Dr. Francis X. Dercum, another of Wilson’s doctors. Dercum advised her, she later claimed, that, were the president to resign, he would lose “the greatest incentive to recovery.” A reduced Wilson could do more good “with even a maimed body than anyone else,” Dercum said.

Marshall, 65, had been Indiana’s governor; his folksy style hid a shrewd political mind, and through the crisis he stayed out of sight. Best known for quipping that “what this country needs is a really good five-cent cigar,” Marshall, fearing to show the ambitions of a “usurper,” decided the only way he would step in would be if Congress were to declare Wilson incapacitated and then only if Edith Wilson and Grayson went along. Privately, Marshall complained that Wilson’s caregivers were keeping him in the dark. The Constitution prescribed no method for removing a disabled president. The decision rested with the incumbent, and the incumbent Wilson showed no desire to step aside.

Collaborating with Grayson to hide how low the stroke had laid her husband, Edith Wilson interposed an invisible but impenetrable barrier between the world and the president. All business that was intended for Woodrow Wilson went through his wife, who withheld anything, even the daily papers, that she feared might trouble him. The doctors had warned Edith Wilson that agitating her husband with upsetting information would be like “turning a knife in an open wound.” Standing by her man, Edith Wilson fended off Lansing and other cabinet members. Even when Marshall paid a get-well call, she turned him away.

The president could not be kept out of sight. By chance, Belgium’s King Albert I and Queen Elisabeth were traveling in the United States. Customarily, visiting heads of state called at the White House. Edith Wilson and Dr. Grayson carefully orchestrated an October 30 audience. A bearded Wilson—he had not shaved for four weeks—received the royals propped up in bed, curtains drawn and room dim. A blanket covered the president’s useless left arm, and staff seated the Belgians to his right, within his limited field of vision. Grayson and Edith Wilson stood by, ready to intervene, but for the duration of the 15-minute encounter Wilson was able to converse. The press reported the visit in a positive light, and the story made the front pages.

Obtaining any presidential action became a chore. Tumulty proved a bottleneck, prompting Wilson’s aides to inundate Grayson with memoranda and requests for action. The physician dutifully relayed these to Edith Wilson, but no one was ever sure if a response would follow.

Grayson flooded the press with Pollyannaish effusions regarding the president’s condition and “recovery.” He knew he was lying, he said later, blaming Edith Wilson’s powerful desire to hide the truth about her husband. Grayson’s bulletins met with skepticism, and Americans sensed something seriously amiss. Rumors multiplied that the president had gone insane, had contracted syphilis, was running naked through the Executive Mansion. Well-meaning citizens bombarded the White House by letter to suggest cures ranging from dandelion wine to Racahant, a concoction of arrowroot and cocoa, to a regime called the Bio-Dynamo-Chromatic System of Diagnosis.

Nearly a century later, it still is not clear how much power Edith Wilson wielded during the 17 months that she referred to as “my stewardship.” Wilson’s wife said she tried only “to digest and present in tabloid form” the matters she thought important enough go to the president and denied making “a single decision regarding the disposition of public affairs,” but admitted that she—and she alone—judged what the president would see. How did she do that? “I just decided,” Edith Wilson said later. “I had talked to him so much that I knew pretty well what he thought of things.” Her agenda was personal, not political. “I am not thinking of the country now,” she told one group of would-be visitors as she rebuffed them. “I am thinking of my husband.”

Instructions and orders to cabinet members came from the president’s wife, no one knowing whether they had originated with her or with the president himself. When David F. Houston was named secretary of the Treasury, Edith Wilson, not the president, interviewed Houston and gave him the good news. Memoranda to the president were returned with notes in Edith Wilson’s handwriting, and messages to the State Department were sent under her name.

Matters grew embarrassing on December 5, 1919, when Secretary of State Lansing was forced to admit before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that he had neither seen nor spoken to the president since September. To head off a congressional inquiry into Wilson’s capacity to govern, presidential aides arranged a meeting between their boss and Sen. Albert B. Fall (R-New Mexico), with whom Wilson frequently sparred, and Sen. Gilbert M. Hitchcock (D-Nebraska). A now clean-shaven Wilson received the Foreign Relations Committee members propped up in bed and flashing signs of his characteristic wit. When Fall told the president he was praying for him, Wilson asked, “Which way, Senator?” However, the visit may not have been a true test of Wilson; during the 40-minute interaction, Fall did most of the talking. The meeting made the front pages.

The entire situation disgusted Lansing. “It is not Woodrow Wilson but the president of the United States who is ill,” he wrote at the time. “His family and his physicians have no right to shroud the whole affair in mystery as they have done.” In February 1920, Lansing was forced to resign because of the cabinet meeting he had called four months earlier. By letter, Wilson belatedly but sternly rebuked Lansing. “[N]o one but the president has the right to summon the heads of the executive departments into conference,” Woodrow Wilson declared, accusing Lansing of the “assumption of presidential authority.”

The extent of Wilson’s disability will never be known, but there is little doubt that he was severely compromised. Sen. George H. Moses (R-New Hampshire) wrote to a friend that the president was “absolutely unable to undergo any experience which requires concentration of mind” and predicted that Wilson would never again be a “material force or factor in anything.”

White House usher Ike Hoover, who had seen Wilson nearly every day for eight years, noted that the president “did grow better, but that is not saying much…There was never a moment during all that time when he was more than a shadow of his former self.” Wilson could “articulate but indistinctly and think but feebly,” Hoover said. Not until March 3, 1920, was the president able to ride in an auto, even as a passenger—and minders shooed photographers before they were able to take pictures of Wilson.

On April 14, 1920, a post-stroke Wilson met with his cabinet. The sight of him shocked Treasury Secretary Houston, who had had last seen Wilson in September. The president “looked old, worn, and haggard. It was enough to make one weep to look at him.” During the cabinet meeting, Houston said, Wilson had “difficulty in fixing his mind on what we were discussing.”

Wilson never believed himself disabled, and even after his stroke toyed with the idea of a third term.

The lack of a fully functioning president became more and more noticeable. In November 1919, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer and sidekick J. Edgar Hoover began rounding up suspected communists on shaky evidence, but there is no indication that Wilson knew of or approved the so-called Palmer raids. On December 2, 1919, the date set for Wilson’s annual message to Congress, the president did not appear, a first. Instead, he sent lackluster remarks Tumulty had written. “I confess I didn’t see any trace of the president in the message,” said House Speaker Frederick H. Gillett (R-Massachusetts), “and I think that is a compliment to the president.” Twenty-eight bills became law without Wilson’s signature or even his attention, and he did not address Congress in December 1920, either.

The biggest impact was on United States entry into the League of Nations. Compromise seemed possible by amending the Versailles Treaty to emphasize that war powers rested with Congress, not the League. Wilson’s supporters tried for a deal; even his wife begged him to compromise and “get this awful thing settled.” The president wouldn’t budge. On March 19, 1920, the treaty—and American entry into the League of Nations—went down to defeat in the Senate. The blow staggered Wilson. He went into a depression, Grayson said, claiming the president complained of feeling “so weak and useless.” However, after Wilson left office he did come to grips with the defeat of the League.

“Do not fear about the things we have fought for,” he told a friend. “They are sure to prevail. They are only delayed.”

Dr. Edwin A. Weinstein, a neuropsychiatrist and Wilson biographer, believed Wilson’s stroke was directly responsible for the treaty’s defeat. “It is almost certain that had Wilson not been so afflicted, his political skills and his facility with language would have bridged the gap” to a compromise, Weinstein said. While never recognizing the degree of his impairment, Wilson seemed to agree, musing to Tumulty, “If I only could have remained well long enough to have convinced the people that the League of Nations was their real hope…”

Wilson completed his term, leaving office on March 4, 1921, and three years later dying of heart disease with his wife and the faithful Grayson at his side. Wilson’s last 17 months in office echoed for years. His cherished League could not prevent a second, epochal world war—though at conflict’s end his dreamed-of entity to mediate international disputes took concrete form as the United Nations, with the United States a charter member. The UN stood, said the late president’s friend and advisor Bernard Baruch, on “the foundations laid with pain and sacrifice by Wilson.” ✯

This story was originally published in the June 2017 issue of American History magazine. Subscribe here.

For more on the 25th Amendment check out Joseph Connor’s article, “The Hardest Call: What Happens When the President Can’t Govern” in our American History web exclusive. To subscribe to American History, click here.