Anyone looking for published primary sources on the Iron Brigade of the West will find much to consider but should start with the classic “Service with The Sixth Wisconsin Volunteers” by Rufus R. Dawes.

It was first published by Dawes in 1890 at a time when veterans were looking back on their soldier days. It was reprinted in the 1930s by his son, former Vice President Charles Dawes, who added photographs, and then again in 1990 by Bob Younger of Morningside Bookstore. There have been other reprints since then.

A native of Marietta, Ohio, Dawes was living in Wisconsin with his father in 1861 when elected captain of a new volunteer company called the Lemonweir Minute Men. It was a name suggested not only by the river near where most of the enlistees lived, but the fact that Dawes, born on the Fourth of July in 1838, and was the great-grandson of William Dawes Jr., who rode with Paul Revere on the night before Lexington.

He attended the University of Wisconsin at Madison for a time before graduating from Marietta College in 1860. In the late 1880s, using his journals and letters, Dawes put in writing with insightful intelligence a memoir of his soldier days at such places as Antietam, Gettysburg, and the Wilderness.

No one wrote better. Of Antietam he said: “Men I cannot say fell, they were knocked out of ranks by the dozens …. Now is the pinch. Men and officers of New York and Wisconsin are pushed into a common mass, in the frantic struggle to shoot fast.”

There is also a certain humility in the account, such as his dismissing of his angry words in a quoted letter home as “youthful vapor.” The Dawes memoir is one of the most important of the Civil War.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Another of my favorites is “An Irishman in the Iron Brigade, The Civil War Memoirs of James P. Sullivan, Sergt., Company K, 6th Wisconsin Volunteers,” (1993), edited by William J.K. Beaudot and myself. It is collection of war tales written by a soldier in Dawes’ Lemonweir Minute Men

He was a “green horn patriot,” Sullivan proclaimed, and no soldier went off to war with a lighter step. He was decidedly Western in manner with a brash wit and the conviction he was as good as any man. He wrote of the war, he said, not only entertain his old comrades, but to “set the record straight.”

Sullivan’s accounts of his experiences at Gainesville (Brawner Farm), Gettysburg, and Petersburg are among the best by an enlisted man who saw much action. He was wounded four times in his four years and lost a finger while building a road of logs.

Another book worth finding is “The Second Wisconsin Infantry” (1984), a series of primary accounts edited by Alan D. Gaff. It includes a long history of the regiment by George H. Otis, one of its commanders, along with letters and recollections by other members of the unit. It is a delightful read.

One should also see the more traditional regimental “History of the Twenty-Fourth Michigan of the Iron Brigade,” by Orson B. Curtis, who lost an arm at Fredericksburg and was active in veteran affairs. It was published in 1891 and includes the usual themes of the era — patriotism, comradeship, memories of the fallen and concern for the widows and children left behind.

Another worthy book is “History of the Sauk County Riflemen Known as Company A, Sixth Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry 1861-1865” (1909) by Philip Cheek and Mair Pointon (1909), an unusual account of a single company. It was written, said the authors, for their own children “and the children of our old comrades.”

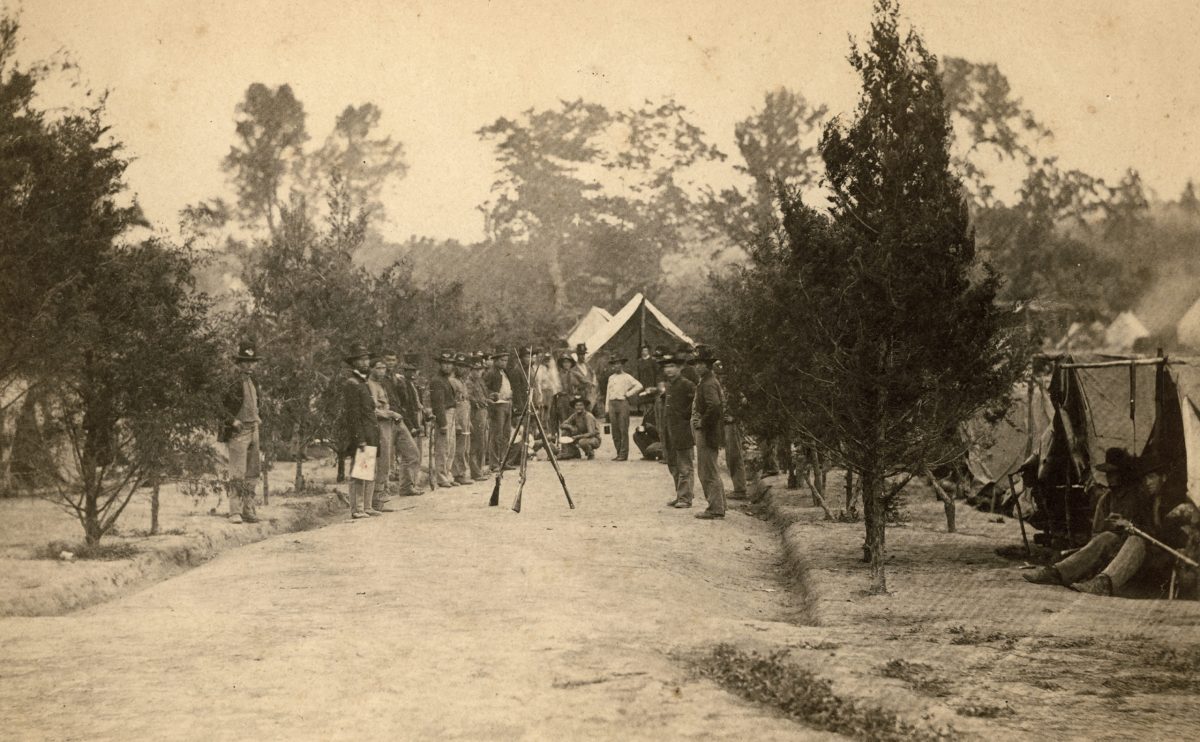

Not to be overlooked is “Four Years With the Iron Brigade, The Civil War Journal of William Ray, Company E, Seventh Wisconsin Volunteers” (2002), edited by Sherry Murphy and myself, a day-by-day account showing not only the boredom of camp life, but the ordeal of Civil War combat.

Wounded at Gainesville (Brawner Farm), again at Gettysburg, and a third time at the Wilderness, Ray witnessed the Petersburg Mine Explosion on July 30, 1864, writing “Oh, how our boys cursed & damned them & damned the officers for not reinforcing our Brave fellows when the Rebs would charge on them.”

New primary source material can also be found in more modern accounts such as the Savas Beatie tribute reprint of Morningside’s “In The Blood Railroad Cut at Gettysburg: The Famous Charge by the 6th Wisconsin” (Herdegen and William J.K Beaudot 1990 and 2002), “Those Dammed Black Hats, The Iron Brigade in the Gettysburg Campaign” (Herdegen 2008), and my own “The Iron Brigade in War, Memory and Thereafter: The Black Hats from Bull Run to Appomattox and Thereafter” (2016).

Of the five regiments, only the 6th and 7th Wisconsin were still active at Appomattox Court House in 1865. The 2nd Wisconsin went off the army rolls in mid-1864 simply used up and three years of enlistment ended. The 19th Indiana was no more, the veterans first folded into the 20th Indiana and then the 7th Indiana.

The 24th Michigan was gone to a draft camp at Springfield, Ill., where it would help in the final burial ceremonies for assassinated President Abraham Lincoln. Battery B of the 4th U.S. Artillery, long connected to the brigade, was returned to its role in the regular army.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.