Fighting didn’t stop when victorious Allies occupied Berlin; instead, it transitioned to politics.

BY THE FIRST DAYS of April 1945, the “Thousand Year Reich” had just one more month to live. American armies had breached the Rhine from the west and had taken major cities such as Frankfurt and Kassel. The British were entering northern Germany. The Soviets, marching inexorably from the east, would soon attack Berlin and become the first Allied nation to occupy Germany’s capital. German resistance was collapsing, and the country was in the throes of defeat.

Frank L. Howley, 42 and then a colonel, was slated to be the director of military government for the American occupation forces in Berlin. Howley felt confident he could work successfully with the ally he and the other Americans knew the least about—the Soviets. “We still had no contact with the Russians” through April 1945, Howley recalled in his 1950 memoir, Berlin Command. As his detachment prepared to leave its temporary base in France and move east, “I optimistically raised my glass and expressed complete confidence that we were going to be firm and fast friends with our allies. It never occurred to me that it could be otherwise.”

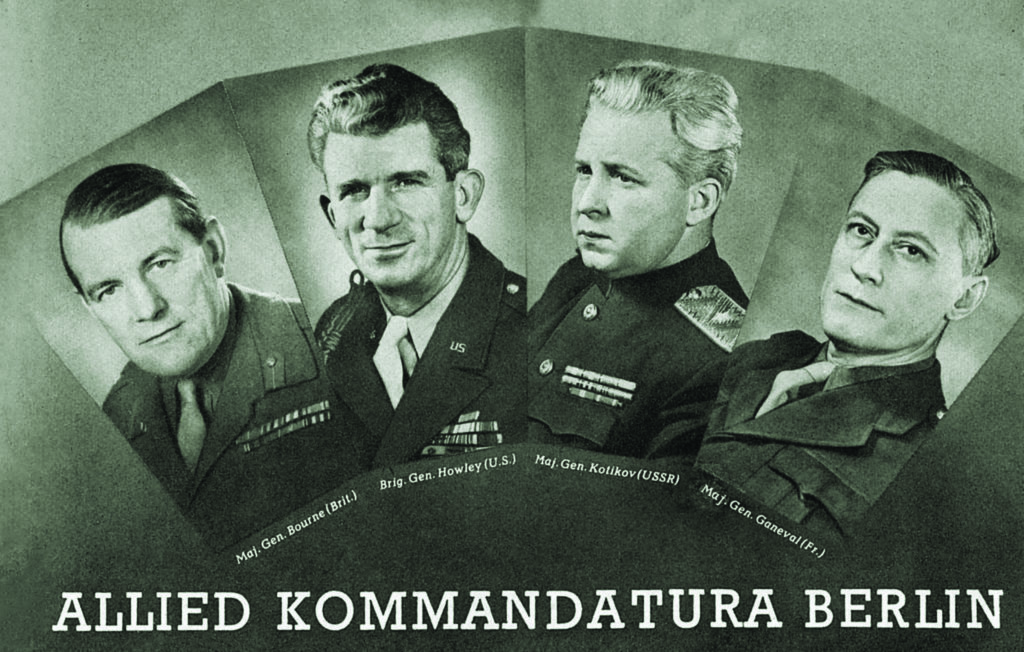

One year later, his optimism was gone. The Western Allies’ relations with the Soviets had turned sour. Howley represented the United States on the Kommandatura, the governing body that ran occupied Berlin. In his memoir he wrote, “I find in my diary for May 1946 the following comment” after a “long, unpleasant meeting: ‘If this type of conference is to continue, we should recognize the failure of the Kommandatura and find some other method of handling Berlin.’ Unfortunately, that type of conference did continue. We were going downhill fast and couldn’t put on the brakes.”

The “unpleasantness” in that meeting stemmed from disagreements over the proposed Berlin city elections. Those elections, to be the first in Berlin since Nazi Germany’s defeat, caused one of the first major post-World War II conflicts between the Soviets and the West. The election campaign was spirited, often angry, even deadly at times, and led to numerous disputes between the occupying powers. After the elections, despite initial hopes for a peaceful new world order, relationships between the Soviets and the Western occupying powers, both in Berlin and worldwide, would only worsen.

IN 1944, the European Advisory Commission (EAC), a negotiating body composed of the U.S., the U.K., and the U.S.S.R, had developed plans for jointly governing Berlin after Germany’s anticipated defeat. The EAC divided the city into occupation sectors—the Soviets in the east, the Americans in the southwest, and the British in the northwest. (Later on, the French received their own sector, drawn from the British zone.) Each occupying power would govern within its own sector. But for citywide matters, the Allies would establish a “Kommandatura”—a Russian term for a military command post—where the French, Russians, Americans, and British would manage the city together, as a team. (An additional four-power governing body, the Allied Control Council, managed all of occupied Germany.)

Robert Murphy, chief State Department adviser to the American military government in Germany, wrote in his 1964 memoir that President Franklin D. Roosevelt “had faith in Soviet-American cooperation,” but that he “regarded Germany as the testing ground.” According to Murphy, “Roosevelt’s mandate” was “to get along with the Russians because Germany, and especially Berlin, was to be the proof whether U.S. and U.S.S.R. postwar cooperation would be possible.”

At the Dumbarton Oaks [Washington, D.C.] Conference in September 1944, the wartime Allies developed plans for a new postwar organization—the United Nations. FDR needed Russian help if the U.N., which would be founded in October 1945, was going to keep world peace. “Roosevelt pictured the U.N. as a substitute for old-fashioned alliances,” wrote Murphy, adding that Roosevelt “believed that protection against future German aggression could be trusted to the troops of Russia, Britain and other European nations.” Dwight D. Eisenhower, military governor of Germany’s American Zone, and Lieutenant General Lucius D. Clay, the deputy military governor, were determined to execute Roosevelt’s guidance as best they could. “We were sincere in our desire to [establish] quadripartite government, which we hoped would develop better understanding and solve many problems,” Clay wrote in his 1950 memoir.

In late May 1945, a month after FDR’s death, President Harry S. Truman sent Harry Hopkins, a trusted FDR aide, to Moscow to confer with Stalin. Washington and London both feared Stalin wouldn’t abide by the pledges he’d made the previous February at the Yalta Conference concerning the administration of the U.N. and other disputed points. But, from Moscow, Hopkins “sent an enthusiastic message…. [He] had persuaded the dictator to make satisfactory compromises,” Murphy wrote. “Because of Hopkins’s optimistic report on Stalin’s attitude, we anticipated few difficulties” with the Soviets.

Clay wasn’t as exuberant: “We were entering into the Allied Control Council with no illusions and we knew that the path ahead would be filled with obstacles.” Journalist Percy Knauth, who wrote for the New York Times and Time and Life magazines during the war, asked Clay in 1945 “how he felt about the prospects of success in the experiment of governing Germany.” Clay answered, “It’s got to work. If the four of us cannot get together now to run Germany, how are we going to get together in an international organization to run the world? It can be done because it MUST be done. We must have patience. It will be tough…. The test is HERE.”

THE AMERICANS assumed control of their occupation sector on July 4, 1945. As bands played the Russian and American national anthems, and General Omar Bradley and the Soviet commandant of Berlin looked on, the Stars and Stripes was raised over a former SS compound. The West entertained high hopes for their new partnership with the Soviets. “Many earnest and honest Americans and Britons had admired Russia for her struggle” against Germany, wrote New York Times correspondent Drew Middleton. “Men of good will believed that the defeat of Germany and Japan would open a new era of good feeling in international affairs based on cooperation between the great powers of East and West.” He added that they “counted on a reasonable amount of cooperation from the Soviet Union.”

At first, things looked promising. Eisenhower and Marshal Georgi Zhukov, the supreme Soviet commander in Germany, hit it off. “General Eisenhower and Zhukov became quite friendly,” wrote Clay. “I was very friendly with Zhukov, and especially friendly with [General Vasily] Sokolovsky,” Clay’s counterpart in Soviet military government. American and Soviet officers socialized frequently. At a party on June 10, 1945, Eisenhower and Zhukov even tried to hum along as a group of African American vocalists sang “Old Man River.” When Japan surrendered, jovial (and undoubtedly inebriated) Americans celebrated with Soviets and sang the traditional Russian folk tune, “Song of the Volga Boatmen.”

The Allied Control Council, located in Berlin, met for the first time on July 30, 1945. Eisenhower attended that meeting; afterward he cabled Army Chief of Staff General George Marshall that he found Zhukov “most friendly and [felt] rather hopeful that he will cooperate in making the Berlin organization an effective machine.” Clay sent a similar message to Washington one month later. He said the Allied Control Council “already was functioning smoothly. The Soviet and other representatives have cooperated cordially,” he reported, adding that “while recognizing that really difficult matters are yet to be faced, I am much encouraged by the general attitude of cooperation and the apparent desire, especially on the part of the Russians, to work with us in solving the various problems.” Colonel Howley acknowledged that the Soviets “cooperated on 95 percent of all issues,” adding that they were “hard bargaining, hard playing, hard drinking, hard bodied, and hard headed. If you are soft, you’d better stay away from them. If you are competent, informed, fair and ‘fearless,’ you’ll get along fine.”

MANY OF THE IMMEDIATE challenges in postwar Berlin were practical, not ideological. The Kommandatura had to rebuild a smashed city and mitigate malnourishment and sickness in its population. Fifty percent of the infants born in Berlin in August 1945 died. Four months after the city fell, when Jewish American soldiers gathered in a Berlin synagogue, the canal next to it “still stank of decayed corpses,” a Chicago Sun reporter wrote. That summer, Allied occupiers “were thinking of the coming winter and the prospect of hunger, disease and general misery,” reported Drew Middleton. Good feelings mixed with necessity spurred the four powers to implement policies and programs that helped distribute food, clear away the rubble, and restore vital services.

The Allied Control Council’s headquarters “quickly became a beehive of activity,” wrote Clay. “An Allied mess was run in the Control Council building. It was always interesting to watch Russians, British, French and Americans eating together and talking through interpreters, in sign language or in some mutually spoken language (usually German), in which few were fluent…. Outwardly good will and good intent pervaded everywhere. Most of us began to think that perhaps this experiment in international cooperation would work. Perhaps it might even lead to the understanding necessary to lasting peace.”

In a 2017 book published by the U.S. Army Center of Military History, The City Becomes a Symbol, authors Donald Carter and William Stivers chronicle the army’s time in Berlin from 1945 to 1949. Carter and Stivers attribute much of the early cooperation to the absence of doctrine in the issues facing the Kommandatura. They note, “In January 1946, Colonel Howley described the military government as an administration of ‘specialists’ whose job was to control epidemics, clear pollution from the waterways, chlorinate the water, resume utility services, weatherproof homes, and reopen banks…. Politics, however, had little to do with their work.” That began to change in early 1946.

IN LATE FEBRUARY, Lieutenant General Clay ordered the U.S. commandant in Berlin to press for citywide elections to choose representatives to the Berlin City Council. Clay wanted to shift the burden of running Germany from Allied to German shoulders—and for that, he needed to reinstitute German civilian government. He noted, “I didn’t know how long the United States was going to be willing to support an occupation.” With the war over, the U.S. Army rapidly shrank its presence in Germany. Colonel Howley brought 150 officers with him into Berlin in July 1945; one year later, only he and three others remained. “President Roosevelt had repeatedly declared during the war that it would not be necessary for American troops to remain abroad very long or in large numbers after military victory had been achieved over Germany and Japan,” Robert Murphy recalled. The American people wanted their men and women home. Germans would have to take over.

Another reason, unique to Berlin, motivated the Americans to seek elections. When the Soviets had occupied the city in May 1945, they installed municipal officials throughout the entire city, not just the Soviet sector. Many of these officials were friendly to, or susceptible to intimidation by, the Soviets and their allies, the German Communists. Frequently, American, British, and French occupation officials found that German civil servants in their own sectors were more beholden to the Soviets than to them. (Some of these officials had flimsy credentials. One glaring—and comical—example: a man the Russians appointed as a chief judge was not a lawyer, but a locksmith.) But a crop of newly elected legislators in Berlin could select different public officials and reduce the influence of the Communists in the city’s government. Not surprisingly, the Soviets were in no hurry to seat a new government and have friendly administrators removed from power.

The Kommandatura had to authorize any election and approve any party that wanted to participate. (In fact, in 1946, if you operated a political party in Berlin without Allied approval, you could be arrested.) Berlin already had four authorized parties in early 1946. Two of them were leftist—the Communists and the Social Democrats. The Social Democrat Party, abbreviated “SPD” in German, was the most popular political party in Berlin. It had Marxist roots but had never subscribed to Soviet-style authoritarianism. Stalin wanted the SPD to merge with the Communists to create a Socialist Unity Party, abbreviated “SED” in German. When the national SPD party leadership refused, Soviet-friendly SPD officials pressed ahead anyway with plans for a quick merger.

The Berlin SPD rank-and-file revolted. On March 1, 1946, over 1,000 party members gathered at the State Opera House and voted overwhelmingly to stay out of the new party. When a leader of the merger effort tried to speak in favor of it, he was “repeatedly interrupted by boos, hisses and calls from the floor,” according to a State Department telegram. And when the same official claimed that the German Communist Party was independent of Soviet control, the “whole audience roared with laughter.”

Antimerger elements arranged for a citywide referendum of SPD members on March 31. Carter and Stivers report that nearly 24,000 party members—more than 72 percent of registered Social Democrats—voted in western Berlin. Meanwhile, polls in the Soviet sector opened as scheduled but were shut down after only an hour by the Soviet authorities, who claimed that election organizers had failed to comply with several “mysterious regulations,” as Howley put it in his memoir. The Soviet tomfoolery failed to prevent the upcoming blow. By a ratio of 19 to 2, Berlin SPD members rejected the merger.

The antimerger forces requested Kommandatura permission to represent the SPD in the city elections. Meanwhile, the German Communists and their SPD allies completed their merger and presented the new SED party to the Kommandatura for approval. At this point, a quirk in both Allied Control Council and Kommandatura operating procedures caused problems. Neither group could operate by majority rule. All decisions had to be unanimous, so any one of the four Allied powers could veto any measure.

The Kommandatura could not agree on letting both the SPD and SED participate in the elections, so they referred it to the Allied Control Council for the four heads of Allied military government in Germany to decide. The Soviet military government leader, General Sokolovsky, could have vetoed any proposal and the Western Allies would have had no recourse. But Sokolovsky didn’t do that. The Allied Control Council agreed to let both the SPD and the SED stand for election within Berlin (alongside the two more centrist parties, the Christian Democrats and Liberal Democrats). The elections were set for October 20.

Sokolovsky’s decision to allow the SPD to split and run against the new SED seems like a headscratcher at first. The Soviets knew how much Berliners hated them for their campaign of pillage and rape as they conquered eastern Germany. But there were sound reasons for the Russians to conclude (or at least hope) they could win Berliners’ votes. “Communism enjoyed significant indigenous support,” Clay noted in his memoir. “It did not depend solely on the bayonets of the Red Army,” he said, adding that Marxism “was an important political movement with deep roots in Germany’s past.” In German elections prior to the Nazi years, Clay pointed out, the combined vote of the Social Democrats and Communists—both with Marxist roots—“approached 40 to 50 percent of the electorate.”

SOVIET POLITICIANS and campaign propagandists trumpeted the U.S.S.R.’s desire to see Germany reunified as one country as soon as possible. They accused the Western Allies of trying to split Germany into eastern and western halves forever. They pointed to the French, who were demanding permanent control of the coal-rich Saar region and wanted the industrial Ruhr put under international authority. There were very few Germans, wrote Drew Middleton in 1945, who did not “look forward to the reunification of eastern and western Germany and few who do not believe that this is essential to the restoration of Germany to something like her old position of prosperity and influence in Europe. The Russians and the German Communists, who have made many mistakes in Germany, have not been mistaken in choosing ‘German unity’ as their principal slogan.”

The Soviets went all-out to win the election. They plastered their sector with posters and banners. “The entire sector reminded me of a newsreel version of Red Square celebrating the October Revolution, with Red banners and huge slogans strung across the streets,” remembered Howley. “Quite a few pre-election food parties were held at SED headquarters,” with the “supplies coming from [common Allied] food stocks. At the schools, they distributed cakes, cookies and notebooks, ‘with the complements of the SED.’”

SPD campaigners in the Soviet sector got rough treatment. The Russians barred speakers and canceled rallies at the last minute. The Soviets menaced SPD members—and regular citizens—in the western sectors, too. Operatives of the NKVD, the Soviet Interior Ministry’s secret police, could reach anywhere in the city, and people often disappeared off the streets, never to be heard from again. The Soviets also dropped hints that the Americans would soon evacuate Berlin. Howley had to reassure worried west Berliners that the Americans “were staying in Berlin, and would stay there twenty years, if necessary.”

It is no exaggeration to say that the whole world was watching the Berlin elections. They would be a “sounding board for the response of the German people to the differing concepts of democracy and government presented by the four jointly occupying powers,” said Colonel Louis Glazier, a U.S. military government representative. “Only in Berlin have the citizens of one city of Germany had actual experience with the different kinds of democracy and the kinds of government for which the various Allied powers stand.… When Berliners go to the polls, many of them will not necessarily be voting for or against any party, but consciously and seriously for one particular concept of democracy.”

Election turnout was huge, with 89 percent of eligible voters casting ballots. The SED was crushed. The SPD won 48.7 percent of the vote; the three West-leaning parties (the SPD, Christian Democrats, and Liberal Democrats) combined to win more than 80 percent of the ballots. Citywide the SED came in third, with 19.8 percent. Russian officials “were downcast,” crowed Howley, adding that the election results were a “great personal defeat in a campaign they had directed with such devious fervor.” The results “must have stunned the Soviet authorities,” wrote Clay, “and made them realize that their hope of gaining control of Germany by normal political methods was futile.”

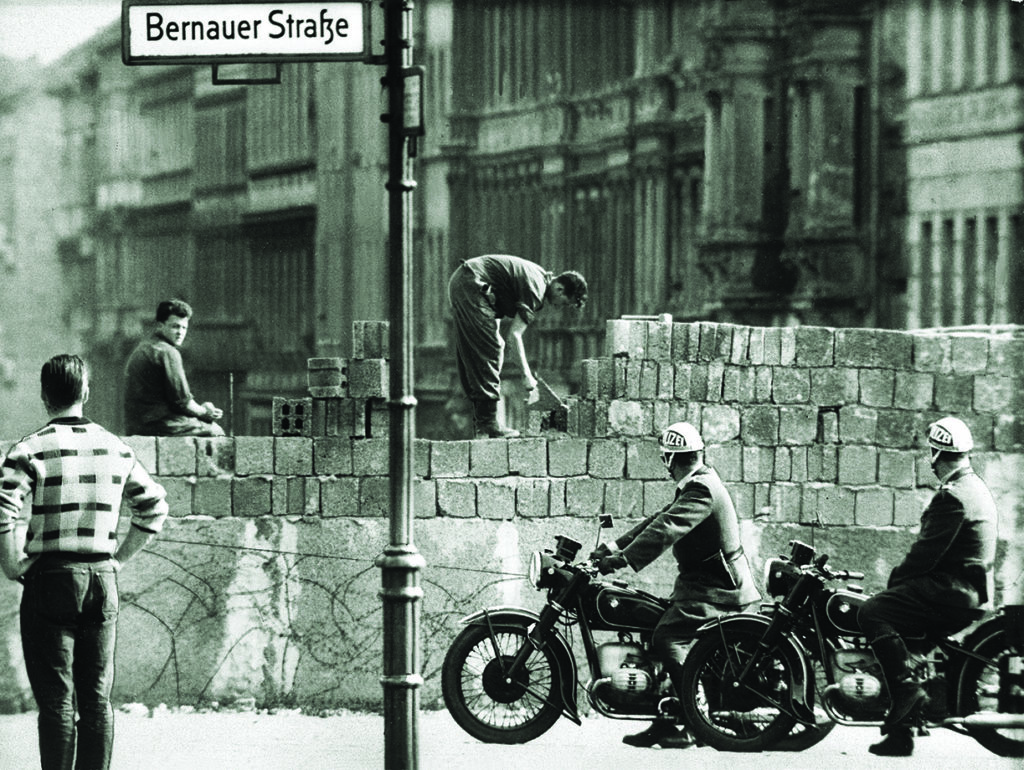

The 1946 Berlin elections were not the cause of the eventual split between the Soviet Union and the West—a split that would lead to the Berlin Blockade and Airlift two years later and the Cold War after that—but the makings were in place. “I’m not sure we could ever have made four-power government work over a long period of time,” Clay concluded in his memoir. “The differences between our systems were just too great.” Unfortunately, Soviet goals and those of the West were incompatible. It became evident to Clay, Howley, and everyone else that all the high hopes of 1945 were dashed. From October 1946 on, the Cold War in Berlin would only heat up. ✯

This article was published in the June 2020 issue of World War II.