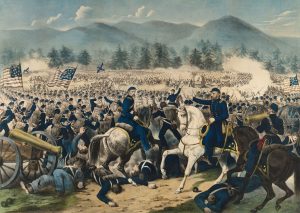

There are 147 national cemeteries in the United States, but none as unique perhaps as Battleground National Cemetery—one square acre of hallowed ground nestled in a residential neighborhood of Washington, D.C. That’s because to be buried at Battleground, you had to be a Union defender of Fort Stevens during the only Civil War battle fought within the boundaries of the District of Columbia on July 11-12 1864. It was during that battle that Abraham Lincoln became the first and only sitting president to come under enemy fire.

Battleground is the nation’s third smallest national cemetery and contains the remains of 40 Union soldiers killed during the battle. But there are 44 headstones. One of the “extra” headstones belongs to Edward R. Campbell who didn’t die until March 10, 1936. In 1864, he was a 19-year-old private in the 2nd Vermont Infantry, one of the 6th Corps regiments sent from Petersburg, Va., by Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant to help defend Fort Stevens. Campbell helped bury the Union dead at Battleground. He survived the war, worked at the Pension Bureau from 1883-1915, and lived in nearby Takoma Park, Md. He was the only survivor of Fort Stevens who chose to be buried with his long dead comrades and his burial closed the cemetery. In an interview he gave just before his death, Campbell said he remembered that President Lincoln appeared during the night while the bodies were being gathered and actually chose the place where the soldiers were to be buried. The story may be apocryphal, but it does add to the mystery and allure of the cemetery.

The other three headstones mark the burial sites of the wife and three children of the cemetery’s first caretaker, Augustus Ambrecht. They died between 1881 and 1885. Ambrecht, an ordnance sergeant and wounded Civil War veteran himself, is not buried at Battleground. There is no record of why his wife and children were allowed to be interred at the cemetery.

Another unique feature of Battleground is that all of the dead are identified. There are no unknowns. Every other national cemetery containing Union Civil War dead have many headstones marked unknown. One of every four soldiers who died in the war were never identified. Why are none of them here at Battleground? On the night of July 12, just after the battle, a unit organized by Captain James M. Moore of the Quartermaster Corps, performed the unprecedented feat of evacuating all of the Union dead from the battlefield and identifying each body. Captain Moore’s unit was the precursor of the Army’s Graves Registration Commission. Their names were hastily written in pencil on small pine boards. It took nearly a decade before those were replaced by marble headstones.

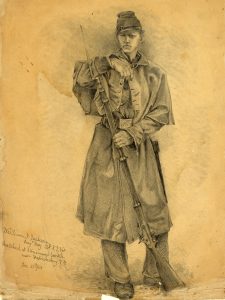

Most of the men buried at Battleground were in their 20s, and four were only 19. Bernard Hoerlo was the oldest. He was 46 when he died and on his second tour of duty with the 98th Pennsylvania Infantry. Most of the men were native born, although some, like Private John Kennedy of the 122nd New York, were born in Ireland.

Private John Ellis of the 61st Pennsylvania had two brothers who fought with him at Fort Stevens. Asaph was in the same regiment, while Horace was in the 7th Wisconsin. Horace was recovering from wounds at a nearby Washington hospital when the call went out for volunteers. He left the hospital and joined his brothers at Fort Stevens. Horace and Asaph probably helped bury their brother John after the battle. Horace would go on to win the Medal of Honor at the Battle of Globe Tavern five weeks later. Both Asaph and Horace survived the war.

Then there’s the tragic irony surrounding 25-year-old Thomas Richardson. Born in Ireland, Richardson enlisted in the Regular Army when he arrived in New York. He fought with the 3rd U.S. Infantry at Manassas, Antietam, and Chancellorsville. Just three weeks before Gettysburg, he was mustered out of service and returned to civilian life in Brooklyn where he became a servant. In February 1864, he quit his job and reenlisted as a private in the 25th New York. He survived some of the war’s bloodiest battles and died in a fight in which he didn’t have to partake.

[dropcap]J[/dropcap]ust because each body had a name doesn’t mean it was the right name. In fact, former National Park Service Ranger Ron Harvey, after years of rigorous research, found that five of the dead interred at Battleground were misidentified. Harvey then went on to find out who they really were. Regulations prohibit changing the names on official headstones because they are part of the historical record, but signage at the entrance to Battleground now correctly identifies each soldier buried here. Private Wilhelm Frei, 25, a German-born blacksmith of the 25th New York Cavalry is buried under a stone incorrectly marked “Wm. Tray.” E.S. Bavett was the only civilian killed during the battle. He served with the local Quartermaster Corps composed of clerks, teamsters, laborers, and government employees hastily assembled and commanded by Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs. Originally he was listed as a member of the 43rd New York. The Battle of Fort Stevens was the only time Montgomery Meigs commanded men in battle. Six Union officers were killed during the fighting—only Lieutenant William Laughlin is buried at Battleground. He was a farmer born in Baltimore and enlisted in Pittsburgh with the 61st Pennsylvania. He had lived through every major battle in the East before dying just eight miles north of the nation’s capital he swore to defend.

There are four monuments in Battleground Cemetery. The one to the 98th Pennsylvania was erected in 1891 and one to the 122nd New York in 1904. The monument to the 25th New York Cavalry memorializes the first reinforcements to reach Fort Stevens on the night of July 10. There is also one recognizing the service of Company K, 150th Ohio National Guard. Company K consisted of Oberlin College students who were 100-day volunteers. They helped man the guns in Fort Stevens during the engagement and the first casualty of the battle, William Leach, was an Oberlin boy. He was wounded on the morning of July 11 while on picket duty. He died four days later. Leach, like 14 other Union fatalities of the battle, is not buried at Battleground.

Accounts differ on whether Battleground is located on the exact spot Lincoln designated. What is known is that this ground belonged to James Mulloy, a farmer, who wanted to build his house on the land appropriated for the cemetery. Mulloy was angry that he lost his land and he sued the Army. In 1868, the government finally settled with Mulloy, who was paid $2,600 for the land.

Every national cemetery originally had a lodge where the caretaker and his family lived. They were called Meigs Cottages because they were designed by Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs. Each was designed in a style known as French Second Empire. The one at Battleground was built in 1871; one of the first to be erected. There is also a Doric-style Rostrum that was built in 1920 and was the site of many Memorial Day commemorations.

There are no Confederate dead at Battleground. When General Jubal Early retreated, he left his dead and wounded behind. Private Thomas Wells, son of Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles and assigned to the staff of General Agar, purportedly led a gang of 50 free black men on the day after the battle to bury enemy dead in mass trenches near where they fell.

In 1874, 17 bodies were disinterred from a mass trench on Thomas Lay’s dairy farm. Thanks to the efforts of Reverend James B. Avirett, they were reburied in a single grave at Grace Episcopal Church not far away in Silver Spring. In 1896, they were moved again and reburied under a 9-foot granite monument paid for by several local Confederate fraternal organizations. It is still the largest memorial stone in the churchyard.

Every national cemetery is hallowed ground for the nation’s veterans buried there. But none can lay claim to the many unique features of Battleground National Cemetery. The cemetery is located at 6625 Georgia Ave NW, Washington, D.C., 20012.

Gordon Berg, a frequent contributor to America’s Civil War, writes from Gaithersburg, Md.