No case has tested the justices of the U.S. Supreme Court more than 1962’s Baker v. Carr. The Court had to hear a second set of oral arguments six months after the first, then hand down six opinions for eight justices. The ninth justice, Charles Evans Whittaker, found trying the case so upsetting he had a nervous breakdown and skipped the final vote. He resigned right after the decision and soon after died. Yet Chief Justice Earl Warren called Baker v. Carr the most important decision rendered in his 16 years on the High Court.

https://historynet.com/brown-v-board-of-education.htm

Baker occurred because Charles W. Baker, mayor of Millington, Tennessee, nine miles north of Memphis, tired of his town getting the short end of the state legislative stick. He signed on as lead plaintiff in a suit the League of Women Voters and other reform organizations organized. The goal was rebalancing state-level representation of residents of cities and suburbs. Memphis, Nashville, Knoxville, and environs had 63 percent of Tennessee’s people but only 13 of 33 state Senate seats. A rural voter enjoyed disproportionate clout: the Memphis area’s seven state senators each represented 20 times the number of residents the senator from farm-filled Moore Country did.

Tennessee’s constitution called for reapportioning the legislature every ten years, but the state still was basing voting districts on the 1900 census. The 1920 census had shown for the first time more Americans living in cities than in rural areas. That shift held, unacknowledged in legislatures. Rural lawmakers were using their legislative majority to starve cities with skinflint outlays for public needs.

The condition was nationwide, with urban- ites shortchanged in as many as 40 states. The 6 million living in the Los Angeles County area had the same punch in California’s legislature as a rural district of 14,000. Burlington, Vermont’s capital (pop. 33,155), had one rep in that state’s lower house; so did Vermont’s least populous district, with just 38 residents.

The situation was profoundly anti-democratic, but city folk had scant recourse. Neither of the routes normally open to political reformers was available to them. Asking legislatures to reapportion to reflect population reality was futile, since rural lawmakers hated to yield power. Going to court was ineffective; judges’ hands were tied by a 1946 Supreme Court mandate in Colgrove v. Green that redistricting was a political question courts were to eschew.

After Baker’s challenge was denied, the justices decided to rethink that 1946 precedent. In oral arguments in April 1961, the lawyer asking that Tennessee’s districts reflect population claimed the extant setup so diluted urban residents’ power as to deny them equal protection as guaranteed by the 14th Amendment. Lawyers for Tennessee Secretary of State Joe C. Carr admitted to the inequalities but insisted the matter was one for the state to address, leaving federal courts no role.

https://historynet.com/american-history-transformation-of-the-us-supreme-court.htm

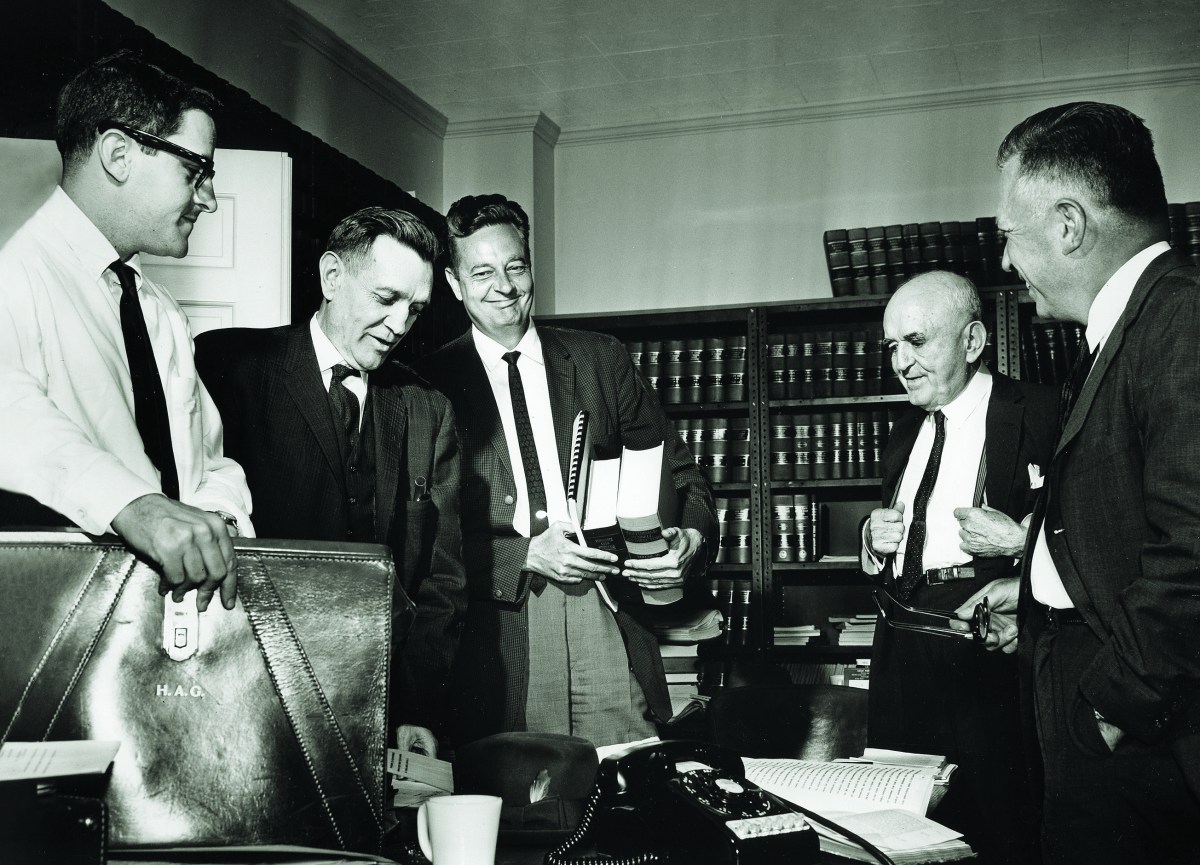

In conference, the justices split harshly, haranguing one another. Hugo Black and William O. Douglas, both dissenters in Colgrove, were joined by Warren and William Brennan in backing mandatory redistricting. Felix Frankfurter, who had written the Colgrove decision, was adamant about upholding its ban on federal court action; he feared that too much intervention in everyday life would cost courts the public’s trust. He had immediate support from conservative John Harlan. Tom Clark hesitated to let federal courts wade into what he saw as political disputes, and Whittaker, though sympathizing with those for redistricting, would not lend a fifth vote to override Colgrove. Potter Stewart ended the discussion by saying he could not make up his mind.

That meant additional oral arguments—three hours in October, in the court’s first-ever morning session. Whittaker was still wrestling with his decision, but Stewart indicated he was leaning toward siding with those who saw in Tennessee’s apportionment a 14th Amendment problem. Clark was in the Frankfurter camp but in trying to write a dissent listing options for would-be redistricters, he realized none existed and tentatively switched sides

Even with Whittaker still on the fence, the Warren side now had a comfortable six votes—if they could hold Clark and Stewart. To achieve that tricky end, Warren’s means was to assign the job of writing the majority opinion to Brennan, rather than to Black or Douglas, longtime foes of malapportionment. Brennan carefully crafted a holding that would not alienate those two wavering pillars.

He acknowledged that the courts had to stay out of political questions, but then focused on the core—and never previously addressed—question of just what constituted a political question. He explored six themes, saying a matter was “political” if 1) the Constitution assigned the decision-making power to a specific department; 2) no judicial standard exists for resolving the issue; 3) any decision would involve making policy beyond the courts’ powers; 4) the court cannot resolve the issue without displaying “lack of respect” for the political branches; 5) “an unusual need” militates against questioning a political decision already made; and 6) a potential for embarrassment impends if various branches of government are making conflicting rulings.

Applying those factors, the decision Brennan wrote did not order Tennessee to redraw its legislative map but did tell reformers they could make their 14th Amendment claims in federal court. That careful solution garnered six votes, but three added their particular views. Douglas underscored that all barriers to apportionment challenges had been removed, Clark said Tennessee was so malapportioned the court should have concluded that it was violating the Constitution, and Stewart insisted that the ruling still left lower courts free to OK a rational apportioning scheme not based on population. Harlan and Frankfurter each wrote dissents. Frankfurter’s was his final opinion in 23 years on the court; he suffered a stroke seven days after Baker was decided and four months later resigned.

https://historynet.com/the-nine-greatest-supreme-court-justices.htm

Reapportionment advocates had little trouble winning challenges in lower courts. And when states sought relief from the Supreme Court in those redistricting rulings, they got no support. Just ten months after the Baker v. Carr decision, the court in a case that originated in Georgia enunciated the “one person, one vote” standard.

The next year the justices applied that principle to drawing district lines for the U.S. House of Representatives. Four months later the Court decreed states could not follow the national pattern of a Senate with representation for geographic areas but had to redistrict both houses of their legislatures only by population. “Legislators represent people, not trees,” Warren wrote. (By then Whittaker and Frankfurter had been replaced by Byron White and Arthur Goldberg, two justices who joined the camp seeing a more expansive role for the federal judiciary in enforcing the guarantees of the 14th Amendment.)

Either under pressure from court cases or the realization that failure to act would trigger such suits, within two years of the Baker decision 26 states had reapportioned their legislatures; 46 had by 1966. That’s why Theodore Olson, solicitor general under President George W. Bush, says, “the decision in this case changed the way we are governed in this country in a very dramatic way.”

This article originally appeared in the October 2021 issue of American History magazine.