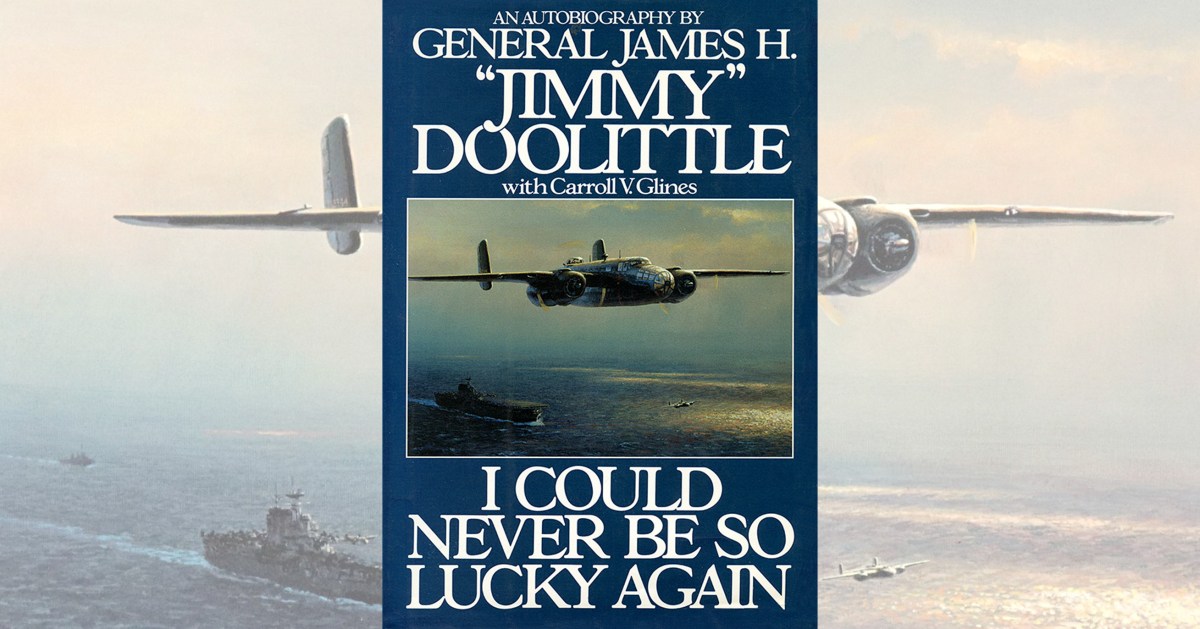

I Could Never Be So Lucky Again by General James H. “Jimmy” Doolittle, with Carroll V. Glines

This is one of those extremely rare literary pairings where the top man in a field collaborates on his autobiography with a top writer who knows the subject. “Jimmy” Doolittle is regarded by everyone as a seminal figure in aviation, a record-setting recipient of the Medal of Honor and a leader in science. C.V. Glines is unquestionably one of the top aviation writers, and has specialized in brilliant biographies. A U.S. Air Force command pilot, Glines doesn’t make any of the mistakes that a nonaviator might, no matter how excellent a writer (c.f. Tom Wolf’s The Right Stuff).

One can immediately sense how closely the two men worked together, since the book reads exactly as if Jimmy Doolittle is talking to you. Doolittle was famous for his frank, friendly but succinct style, and the autobiography brings you not just the essence but the very being of a man whose extraordinary career spanned nine decades.

Doolittle is best known for leading the famous April 18, 1942, raid on Tokyo, and the book begins with the ultimate insider’s look at that fateful mission. No one knew it better nor could recount it as well as Doolittle. He presents the raid from start to finish, bailing out of a fuel-empty North American B-25B in the wilds of China. Far from being the failure that Doolittle considered it at the time, the raid achieved much more than had been planned for it. President Franklin Roosevelt and Doolittle’s seniors had hoped the 16- bomber strike would boost American morale at a time when all military news was catastrophic. The raid boosted morale enormously, but more important, the Japanese reacted with an ill-considered decision to attack Midway Atoll. That set them up for the defeat that reversed the course of the war.

The book paints a moving portrait of Doolittle’s hardscrabble beginnings in Nome, Alaska, where young Jimmy, a fighter from age 5, proved that poverty, relatively small stature and no apparent advantages would not bar success, no matter what the odds. Recalling a time when his father falsely accused him of lying, Doolittle writes simply: “I didn’t lie then and I don’t lie now. I told him that when I was big enough, I was going to whip him.”

Doolittle had to whip many people, planes and events in his lifetime, and he always managed it with the same deductive thought processes that made him, in Glines’ words, a “master of the calculated risk.” Early on, a boxing coach brought his flailing aggression under control and introduced him to the subtleties of anticipation, feinting and balance, all skills he would use in aviation. A 5-foot-4-inch bantamweight, he fought successfully as an amateur and a professional just before meeting his first love and acknowledged salvation—Josephine Daniels, his beloved “Joe.” She became the keel and rudder of his career; as Bob Hope’s wife Dolores said at a 1984 award ceremony: “He spent 45 years in the air. Joe Doolittle spent 45 years waiting for him to land.”

Just how appropriate this autobiography’s title is becomes apparent as Doolittle’s life unfolds—his sometimes madcap Air Service flying, earning both masters and doctoral degrees in science at MIT, and his many racing triumphs. These included winning the Schneider Cup and both the Bendix and Thompson trophies. It was Doolittle’s custom to push any aircraft to the limits, and when science demanded, beyond. Racing fans will revel in his approach to the notorious Gee Bee R-1: “I didn’t trust this little monster. It was fast but flying it was like balancing a pencil or an ice cream cone on the tip of your finger.” He decided that “it would be prudent to stay outside of the rest of them [the other racers] and climb before the pylons, dive before each turn, but remain outside.”

As thrilling as the accounts of his legendary flying are, many people will find that this book’s most rewarding aspect is the understanding it provides of the breadth of Doolittle’s vision, scientific capacity and leadership capability in peace and war. The fact that modern pilots can rely on instruments to help them fly safely in heavy weather and at night can be traced directly back to Doolittle’s work with cockpit instruments and “blind flying.” He himself said that “This work was, I believe, my most significant contribution to aviation.” Doolittle comments on his first true instrument flight on September 24, 1929, in typical low-key manner. After ex – plaining how he became the first person to take off, fly a circuit and land completely on instruments, he concludes, “However, despite all my previous practice, the approach and landing were sloppy.” This is like Alexander Fleming saying, “I discovered penicillin, but my Petri dish had a smear on it.” Doolittle is, to my knowledge, the only man to be awarded both the Medal of Honor and the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Although Doolittle violated military custom by leaving the service to serve in the Reserves for a decade, he returned to it in 1940 with gusto. The Tokyo Raid was only the beginning of his contributions; he rose to command the mighty Twelfth, Fifteenth and Eighth air forces. At the Eighth he changed the course of the war by putting its fighters on the offensive, breaking the Luftwaffe’s back.

I Could Never Be So Lucky Again improves with each rereading because it is so content laden. Glines lets Doolittle be Doolittle, but he incorporates an incredible number of salient facts. I urge any first-time reader to scan the career summary, which outlines Doolittle’s staggering series of accomplishments in civil and military roles. No library should be without this book, and no writer should attempt either an autobiography or a biography without studying its style.

Originally published in the March 2009 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.