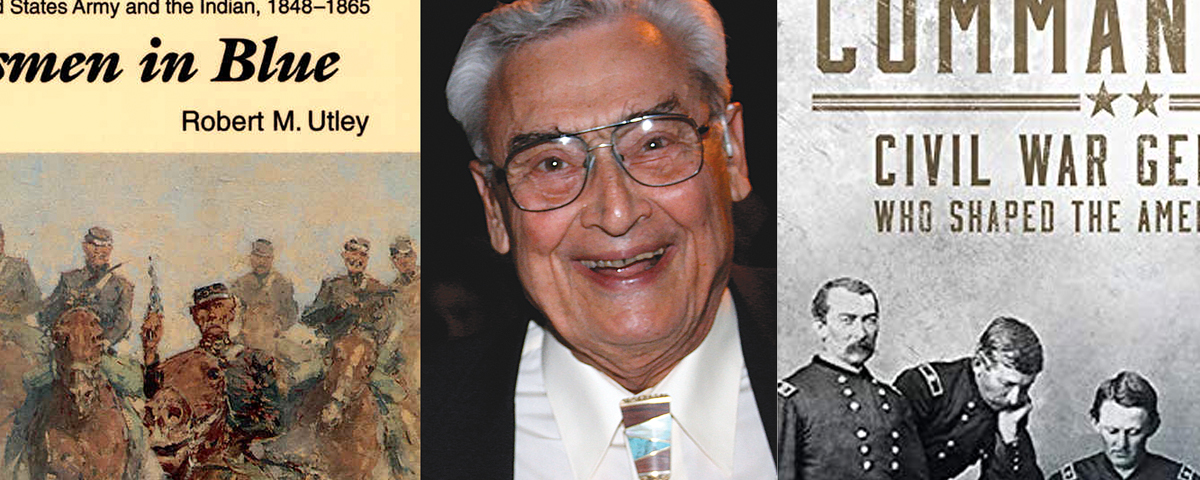

Robert M. Utley, a former chief historian for the National Park Service, has been recording the history of the American frontier—particularly its military history—for decades, and he shows no signs of slowing down anytime soon. He has written or edited more than 20 books, including Frontiersmen in Blue, Frontier Regulars and Cavalier in Buckskin: George Armstrong Custer and the Western Military Frontier. All three are essential references for anyone writing about the frontier Army. And 2018 saw another command performance from Utley, namely The Commanders: Civil War Generals Who Shaped the American West. In it Utley profiles seven key commanders—Christopher C. Augur, George Crook, Oliver O. Howard, Nelson A. Miles, Edward O.C. Ord, John Pope and Alfred H. Terry—and provides his own informed analysis of their abilities.

What strengths did these commanders share?

They were all Civil War veterans who had served in general officer rank and bore one or more brevets for distinguished service. That background gave them a self-confidence and self-esteem, reinforced by gaining general officer rank in the postwar Regular Army, that equipped most for their mission.

Which of them was most effective?

I give first place to General Christopher C. Augur. He is virtually unknown, and his place at the head of the list doubtless comes as a surprise, and an arguable one at that. His low profile is attributable to his quiet modesty and his role as a desk general rather than a field general. But he oversaw the execution of a number of successful field expeditions in his department, ran an efficient headquarters and got along well with superiors and subordinates. Augur’s commands ran smoothly without adversity.

What weaknesses did they share?

They were hobbled by inability to adapt to the Indian mode of warfare. They were experienced in the conventions of the Mexican and Civil War and brought that with them to the West. Even Crook, the best at breaking free from convention, had some failures he refused to admit. It is not altogether fair to blame the generals for this flaw. It was in large part institutional, embedded in organization and doctrine of which they were captive. A weakness of which all were guilty was blatant use of political influence to gain promotion, especially common because the president made all appointments of general officers.

‘The treaty was the worst possible mechanism for regulating relations between Indians and whites. Neither side clearly understood what was being promised, and neither side honored the commitments’

How would you compare the various 19th-century treaty conferences?

I don’t compare them; I judge them all failures. The treaty was the worst possible mechanism for regulating relations between Indians and whites. Neither side clearly understood what was being promised, and neither side honored the commitments. The most prominent was the peace commission of 1868. It defined shrunken homelands both north and south, a definition dictated by the government. Subsequent wars found their origins largely in those treaties. I can’t think of any treaty or commission I would judge a success.

The seminal events in frontier military history?

The Great Sioux War of 1876 takes first place. The Red River War of 1874–75 follows. The Apache wars, notably the Geronimo operations of 1885–86, have a prominent place. The Nez Perce War of 1877 is notable. Before the Civil War, the Rogue River and Yakima wars in the Pacific Northwest exposed to Indian warfare many young officers who later became generals. Both before and after the Civil War, the long-running contention with Comanches and Apaches on the Texas frontier is a major story.

What can you say about the wives of the commanders you researched?

In the army domestic structure the general’s wife was a person of significance. Most had struggled up the chain of command, their place in the social hierarchy determined by their husband’s rank. When hubby became a general and department commander, they lived in a city or close to one. Their social status changed accordingly. The generals I dealt with had successful marriages. The notable one was the wife of Nelson A. Miles, who also was the niece of General William T. Sherman and Senator John Sherman. She was nearly as ambitious as her husband and backed his effort to get the general of the army to advance his professional fortunes. General Sherman constantly refused; he detested nepotism. Miles was too vain to understand that. Crook and Ord had particularly successful marriages.

You’ve written about Kit Carson, Jim Bridger, Jedediah Smith and the like. How do you compare such frontiersmen’s leadership styles with those of the Civil War generals?

Kit Carson became a colonel of New Mexico volunteers and led them well but was hardly comparable to the generals in my book. The trappers named were individualists. When they led—say, fur brigades—a different kind of leadership was called for. They could not rely on military discipline but had to depend on their personal people skills. They were all good at it, but not in a military sense.

Which frontier military histories top your list?

Of course I have to rank my two frontier military books close to the top. Also significant is Robert Wooster’s The American Military Frontiers: The United States Army in the West, 1783–1900. Edward M. Coffman’s The Old Army: A Portrait of the American Army in Peacetime, 1784–1898 contains much on the frontier Army.

What are you working on?

Let’s say it’s a story not yet jelled in my mind. I once did a biography of Sitting Bull. Now I am contemplating a book treating his four years (1877–81) as a refugee in Canada. This is to be the story of the friendship of two men: Sitting Bull and Major James M. Walsh of the North-West Mounted Police. Walsh was the first and probably only white man Sitting Bull trusted. The story ends when Sitting Bull had to surrender at Fort Buford because of starvation. WW