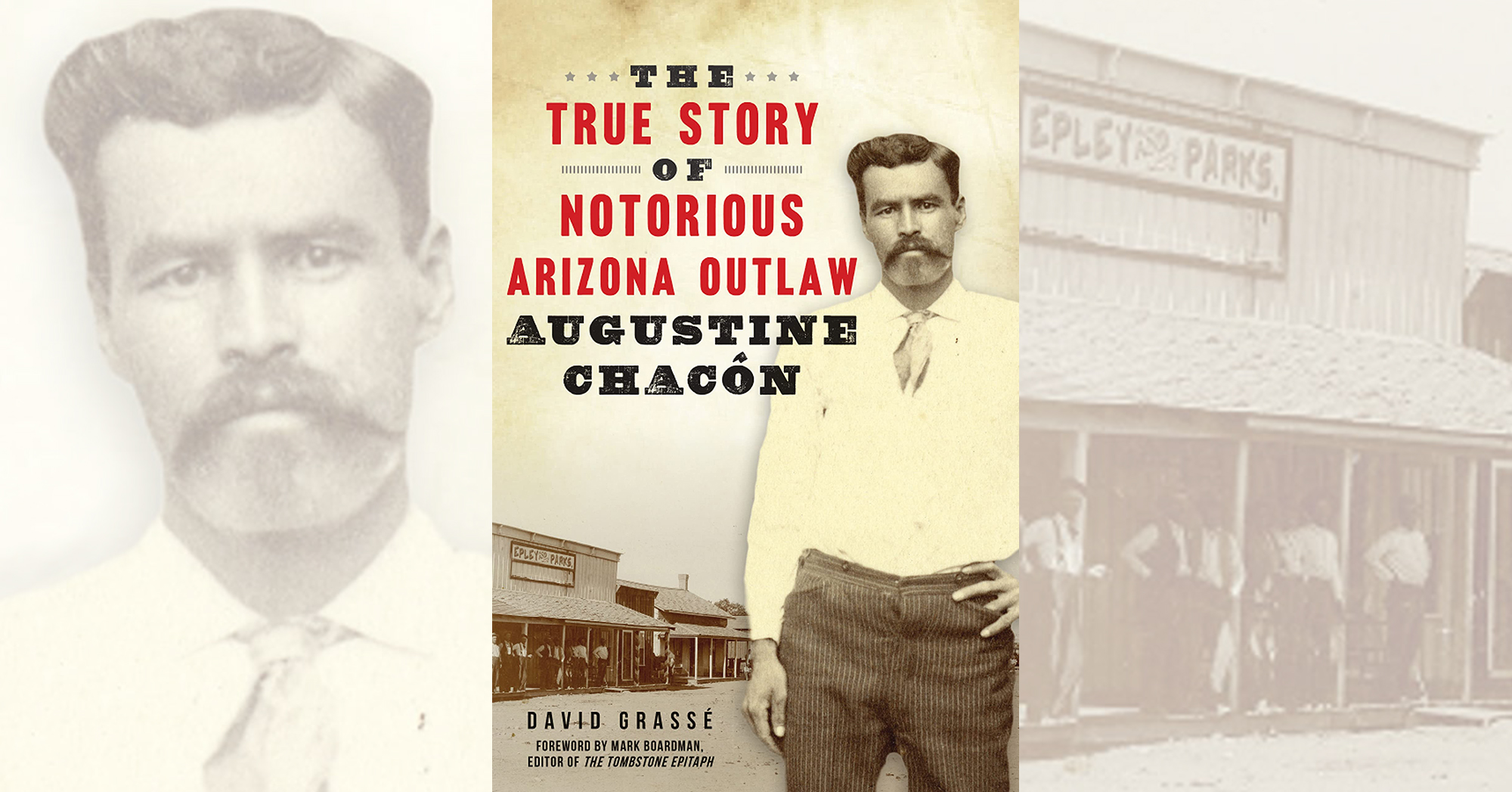

The Story of Notorious Arizona Outlaw Augustine Chacón, by David Grassé, History Press, Charleston, S.C., 2021, $33.99

Among the more infamous killers in Arizona lore, Augustine Chacón reportedly murdered as many as 52 people, escaped jail and his own imminent hanging on June 9, 1897, was recaptured by Arizona Ranger Captain Burton C. Mossman in September 1902 and faced his second rendezvous with the gallows on November 21 of that year with a fearless, remorseless calm that impressed all who witnessed it. Coming at a time when the Old West was rapidly giving way to the 20th century, the rise and fall of a hell-raising villain with Chacón’s attributes—catchy name included—seemed almost too good to be true. According to Arizona-based reference librarian David Grassé, who plumbed period records and journals, practically all of what has been passed down over the past century on Chacón is just that—too good (or bad?) to be true. The product of his research is less of a biography than a fascinating study on how sensationalism can take a grain of truth and snowball it into disproportionate myth.

Little was known of Chacón until Dec. 17, 1895, when a botched burglary in Morenci led to a gunfight that left two perpetrators dead, along with bartender Pablo Salcido, shot while overzealously aiding Constable Alexander Davis. A wounded Chacón was taken into custody. Surviving records enabled Grassé to present an account of the subsequent trial and conviction of Chacón for Salcido’s murder—despite testimony and evidence that left more than just a shadow of a doubt—and details of how Chacón managed to dig his way out of a jail cell in Solomonville on the eve of his execution. From then on, however, hard facts on his whereabouts ceased, but speculation stampeded, as virtually every robbery or killing in Arizona was “believed to be” the work of Chacón or his “gang.” As he sifted through such accounts, the author noted the repeated use of that disclaimer “believed to be,” an abuse of the passive voice that omits the source of the rumors. Adding to the absent Chacón’s sinister public image were longstanding cross-border prejudices toward Mexicans, into which his depredations—real or not—were shoehorned. By 1902 such attitudes had elevated the fugitive into a notorious serial killer who would have to pay the ultimate penalty.

Just before hanging, Chacón requested and was granted a half hour to make a final statement, most of which he spent accounting for his time in Mexico and giving a last protestation of innocence regarding Selcido’s death. At his appointed time his last words were, “Time to hang,” and thanks to his jailers. Not content with that bland farewell, the Bisbee Daily Review attributed to him the more defiant, “I consider this to be the greatest day of my life.”

Grassé deconstructs a legend that has been dutifully repeated in history publications ever since (including by this embarrassed writer in an April 1991 Gunfighters & Lawmen article in Wild West). Sloppy editing occasionally trips up what is essentially an intriguing read that reveals how a minor felon was hoisted to criminal heights. The legendary Chacón, the author maintains, was the product of yellow journalism, xenophobia and racism—a potent brew that has yet to disappear from present-day newspapers.

—Jon Guttman

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.