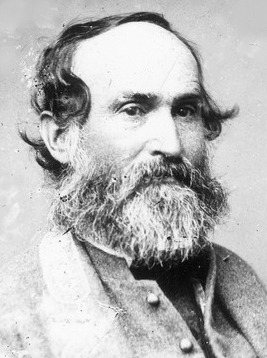

On the blistering hot afternoon of July 11, 1864, bold, battle-hardened Lieutenant General Jubal Anderson Early sat astride his horse outside the gates of Fort Stevens in the upper Northwestern fringe of Washington, D.C. The enigmatic 47-year-old Confederate, a veteran of Antietam, Gettysburg, the Wilderness and countless other fights, was aboutto make one of the Civil War’s most portentous decisions: whether or not to order his 10,000 veteran troops to invade the United States capital.

Almost exactly one month earlier, Early’s commanding general, Robert E. Lee, had made a bold, risky decision of his own. He had ordered Early’s Second Corps to cut itself out of the Army of Northern Virginia, which was hunkered down outside Richmond awaiting the next move by Union Army commander Ulysses S. Grant. The Federals had massed an unprecedented number of troops outside the Confederate capital, the final element in what Grant called his grand campaign to end the war.

In the predawn hours of June 13, Early marched his men out of their Richmond-area encampment and into the Shenandoah Valley. Lee had ordered Early to wreak havoc on Yankee troops in the Valley, then to move north and invade Maryland. Lee envisioned an audacious mission: to free some15,000 Confederate prisoners at the Point Lookout POW camp east of Washington in southern Maryland, and then, if Early believed the conditions were right, to take the war for the first time into President Abraham Lincoln’s front yard. Lee’s agenda also included forcing Grant to release a significant number of troops from the stranglehold he had built around Richmond.

Early enthusiastically followed Lee’s orders. He routed bumbling Maj. Gen. David Hunter at Lynchburg on June 18, then swiftly and stealthily moved his men through the Valley, crossed the Potomac at Shepherdstown, W.Va., on July 5 and slowly began to move east into Maryland. Panic erupted in the streets of Washington—and in Baltimore 35 miles to the north—when word reached the citizens that Early’s troops were heading in their direction. Washington, although ringed by an impressive array of interconnected forts and earthworks, was drastically underdefended in July 1864 because Grant had brought nearly every able-bodied soldier from its defenses down to Richmond and Petersburg to take part in his siege.

The First Hurdle: Monocacy

Early did not want to fight a full-scale battle in Maryland. His goal after crossing the Potomac was to march on Washington, just 50 miles to the southeast, and to free the Confederate prisoners at Point Lookout. Lew Wallace, the Indiana general who had been disgraced at Shiloh and was serving penance as the commander of the Union Middle Department in Baltimore, had other ideas. On his own, without any direction from a clueless War Department and Army high command in Washington, Wallace moved about 2,800 men, most of whom were short-term enlistees from Ohio, early on the morning of July 6 to defensive positions on the east bank of the Monocacy River four miles south of Frederick, Md. Wallace set up his defense at the Monocacy Railroad Junction, a vital crossroads where the National Pike led to Baltimore and the Georgetown Pike to Washington.

At almost the last moment, just before daybreak on Saturday, July 9, a contingent of 3,000 VI Corps troops under Brig. Gen. James B. Ricketts arrived on the scene, having marched from their positions on the outskirts of Richmond to City Point on the James River before taking steamers to Baltimore and trains to Monocacy. What followed a few hours later was a daylong battle in which Early’s numerically superior force of veteran troops defeated Wallace’s cobbled-together contingent.

But Early’s victory at Monocacy came only after hours of intense fighting that left just under 1,300 Union dead, wounded or captured and resulted in 700-800 Confederate casualties, primarily among Maj. Gen. John Brown Gordon’s brigade, which met the bulk of Ricketts’ men in three brutal assaults amid corn and wheat fields on both sides of the river. Late that afternoon Wallace retreated to Baltimore, while Early allowed his men to rest overnight on the battlefield.

To the Gates of the Capital

The following morning, July 10, Early’s forces began to move out along the Georgetown Pike on a straight line toward Washington. The going was slow because of the punishing heat and the exhaustion the men still felt from the march through the Valley and the hard fighting at Monocacy. Early spent that night bivouacking in and around the cities of Rockville and Gaithersburg, about 10 miles outside Washington.

Union commanders scrambled to put together a force of volunteers to defend the city as panic continued to grip its inhabitants. Army Chief of Staff Henry “Old Brains” Halleck urgently put out the word for more volunteers. “We are greatly in need of privates,” Halleck said. “Any one volunteering in that capacity will be thankfully received.”

Unlikely prospective privates immediately offered their services. On the night of July 10, “the motliest crowd of soldiers I ever saw,” as one soldier observed, was organized primarily to man Forts Reno and Stevens, the two largest forts guarding the northwest quadrant of the city. The motley crew consisted of, among others, quartermaster employees, staffers from the War, Navy and State departments and convalescents from military hospitals. Or, in the words of another Union soldier, a collection of “counter jumpers, clerks in the War Office, hospital rats and stragglers.”

At 6:20 the next morning, Early’s men began moving out from Rockville and Gaithersburg. When they were within a few miles of the capital, they exchanged fire with Union pickets. The Confederates then marched to Silver Spring, just outside the city. Early himself arrived a short time after noon and reported that the defenses of Washington were “but feebly manned.”

At 8:45 p.m. on July 9, just a few hours after Wallace’s defeat at Monocacy, Halleck had relayed an order from Grant to Maj. Gen. Horatio Wright, the 44-year-old commander of the Army of the Potomac’s VI Corps, outside Richmond. The order instructed him to bring the remaining two divisions of his corps “at once” to City Point, get them into troop transport ships and report to Halleck as soon as they arrived in Washington. The ships made it to the old Sixth Street Wharf in Washington at noon on the 11th—just as Early was contemplating Fort Stevens for the first time and pondering an attack on the “feebly manned” post and city.

But Early held back. The heat and long march had taken its toll on his men. “When we reached the right of the enemy’s fortifications” at Fort Stevens, Early informed Lee three days later, “the men were almost completely exhausted and not in a condition to make an attack.” By the time Early felt his men were ready, it was too late. Union VI Corps men had been rushed into place at Fort Stevens, rendering any prospect of a successful assault remote at best.

So Early decided not to invade Washington, and the Point Lookout raid was called off. Early, however, stuck around the capital for two days to wreak other kinds of havoc. He and his men engaged Union forces outside Fort Stevens and Fort Reno in 48 intermittent hours of skirmishing that resulted in some 300 Union casualties and an equal, if not larger, number on the Confederate side.

Lincoln made brief appearances on July 11 and 12 to see for himself what was happening at Fort Stevens. On the 12th, while Lincoln was standing on the fort’s parapet, a Union officer next to him was shot by a Confederate sharpshooter firing from a tree on what is now the grounds of the Walter Reed Army Hospital. That marked the first—and only—time in American history that a sitting U.S. president came under hostile fire in a military engagement.

Early on Wednesday morning, July 13, Early took his troops back into Virginia. The Union forces did not give chase. The “great rebel raid,” New York Times correspondent William Swinton reported on the front page of the newspaper’s July 15 editions, “is over.” It “abruptly ends the boldest, and probably the most successful of all the rebel raids.”

The Big Questions

Strong differences of opinion remain about the momentous questions and decisions involved in Early’s great rebel raid. Did Wallace’s stand at Monocacy save Washington by delaying Early just long enough for Grant to send experienced troops to stop the invasion, and what effect did sending those troops have on Grant’s plans for the summer of 1864? The most contentious question has been whether Early could have—and should have—invaded Washington. Debate also continues about the success of Early’s campaign, and the overriding question of what impact the invasion of Maryland, Wallace’s stand at Monocacy and the Confederates’ march on Washington had on the course of the Civil War—and on American history.

What can be said with certainty is that Lee forced Grant to part with the VI and XIX corps, the latter of which had been on its way to Richmond from Louisiana before Grant reluctantly ordered it to go straight to Washington. There is no doubt that moving all those troops away from Richmond in the first week of July altered Grant’s strategic timetable for a final push to end the war. But the other big questions remain.

Some observers, primarily but not exclusively Northerners, believed at the time that Washington was there for the taking when Early arrived at Fort Stevens at midday on the 11th. Lieutenant Colonel Aldace Walker of the VI Corps’ 1st Vermont Heavy Artillery Regiment (formerly the 11th Vermont Infantry) was part of the Union contingent that eventually defended the fort. He wrote in his 1869 memoir that he had “little doubt” that Early “might have taken [Washington] on either of the two days he spent in its neighborhood before” the VI Corps’ arrival from Petersburg.

Sylvanus Cadwallader, a Union war correspondent who was in Washington on July 11 and 12, agreed. “I have always wondered at Early’s inaction throughout the day [of Monday, July 11], and never had any sufficient explanation of his reasons,” he wrote in his 1896 war memoir. “Our lines in his front could have been carried at any point, with the loss of a few hundred men.”

Early “passed the night of the 10th within five miles of Washington,” Treasury official Lucius Chittenden wrote in his memoir. “Presumptively, he could have attacked the next morning, when a considerable portion of his force was at Silver Spring and above Georgetown, within two miles of the defences.” Had Early attacked on the morning of July 11, Chittenden postulated, he “would have met with no resistance expect from the raw and undisciplined forces, which, in the opinion of General Grant, and it was supposed of General Lee also, would have been altogether inadequate to its defence.”

Union Brig. Gen. Nelson A. Miles, who commanded a brigade at Petersburg while Early was invading Maryland and would eventually become a lieutenant general in the U.S. Army after the war, believed that Early squandered a golden opportunity on July 11. “Had Stonewall Jackson been in command of that force,” Miles wrote in his 1911 memoir, “the result would undoubtedly have been very serious, if not disastrous, to the Union cause.”

Presidential secretaries John Nicolay and John Hay, in their famed biography of Lincoln, accused Early of making “a serious error” on July 11 “in regard to the troops in front of him.” Early “always looked at his own force through the wrong end of his field-glass,” the authors wrote. That caused Early to pause, they said, and make “the most careful preparation.” But “before the preparations were completed, what he had imagined had become true: Wright with his two magnificent divisions had landed at the wharf, being received by President Lincoln in person amid a tumult of joyous cheering….”

Horace Greeley, the passionately anti-slavery, pro-Union editor of the New York Tribune, also believed Early could have “taken the city,” but only if he had “rushed upon Washington by forced marches from the Monocacy, and at once assaulted with desperate energy” on July 10. Even in that case, the mercurial editor wrote two years after the war, Early “might have lost half his army.”

Early’s lieutenant, Maj. Gen. Stephen Dodson Ramseur, also believed an assault would have been costly. “Natural obstacles alone prevented our taking Washington,” he wrote on July 15. “The heat & dust was so great that our men could not possibly march further. Time was thus given the Enemy to get a sufficient force into his works to prevent our capturing them.” According to Ramseur, by the morning of July 12, the Union had “more men behind the strongest built works I ever saw than we had in front of them.”

The “trip into [Maryland] was a success,” Ramseur wrote to his wife a week later. He noted that the Richmond newspapers were “‘pitching into’ Gen’l Early for not taking Washington.” But he defended his commander by arguing that if Early “had attempted it, he would have been repulsed with great loss, and then these same wiseacres would have condemned him for recklessness.”

Major Jedediah Hotchkiss, the famed topographical engineer on Early’s staff, echoed Ramseur’s words in a letter he wrote to his wife on July 15. On “Monday [July 11] we went up to the fortifications, & within 6 miles of the President’s House, but our Men were so much exhausted by the intense heat (I have never experienced warmer weather) that we could not go on to the assault of the works that morning….”

A Great Success?

Journalist and Lincoln confidant Noah Brooks characterized Early’s campaign as a strategic success. If “the invasion of Maryland was designed to create a diversion from Grant’s army, then in front of Richmond, that end was successful,” Brooks wrote in 1895. “And while a great force of effective men was kept at bay within the defenses of Washington, the bulk of Early’s army was busy sweeping up all available plunder, and sending it southward across the Potomac.”

Brooks went on to say that the news of Early’s invasion also had a significant impact on Northern morale. “In the country at large,” he said, “the effect of this demonstration was somewhat depressing. The capital had been threatened; the President’s safety had been imperiled; only a miracle had saved treasures, records, and archives….”

Journalist and author Edward A. Pollard, a Southern partisan, wrote in 1866 that “the results” of Early’s mission to Maryland “fell below public expectation [in] the South, where again had been indulged the fond imagination of the capture of Washington.” But, Pollard said, “the movement was, on the whole, a success.” Pollard claimed the main reason was because Grant “had been weakened, and the heavy weight upon Gen. Lee’s shoulders lightened.”

Alfred Roe, a Union private who as a POW had witnessed the fighting outside Fort Stevens, wrote in 1890 that Early “personally told me that he found, on facing Fort Stevens, that the purpose for which he was sent by Lee had been subserved; i.e, some troops, he knew not how many, had been drawn from Petersburg, and this very arrival, while it blocked his entrances, lessened Lee’s danger.”

Although Grant did not address the success or failure of Early’s mission in his memoirs, he did speak of “the gravity of the situation” in Washington on July 10 as Early “started on his march to the capital of the Nation.” Grant said he came to believe that Washington was only vulnerable on July 10 before Early had arrived, but not on July 11 and 12. “If Early had been but one day earlier,” Grant said, “he might have entered the capital before the arrival of the reinforcements I had sent.”

Early’s Version

Early himself sounded off about his reasons for not pushing into Washington soon after the affair ended. His version of his mission, which he continued to expound throughout his long life, in the main agreed with those who argued that an attack on July 11 or 12 would have been foolhardy.

Beginning on July 14, 1864, the day after he crossed back into Virginia, and to his dying day 30 years later, Early considered his four-week campaign a great success. He also maintained that the reason he did not invade Washington on July 11 was because his men were near exhaustion and that he didn’t invade on July 12 because he would have faced a force of numerically superior veteran Union troops, protected by forts and entrenchments.

Early laid out his main points for the first time in the after-action report he sent to Lee on July 14. First, he said, he didn’t hesitate when he arrived at the outskirts of Fort Stevens on July 11 because he had mistaken the ill-equipped troops he saw for VI Corps men, but rather because his men were not physically capable of attacking at that time. Second, that same day he saw for himself that the Washington defenses were nearly impregnable. The fortifications, he reported, “we found to be very strong and constructed very scientifically.” Third, despite points one and two, Early decided to attack on Tuesday morning, July 12, but changed his mind only at the last minute when he saw that the VI Corps troops had indeed arrived at the Washington forts. After “consultation with my division commanders, I became satisfied that the assault, even if successful, would be attended with such great sacrifice as would ensure the destruction of my whole force,” he said. “If unsuccessful,” Early continued, it would have “resulted in the loss of life of the whole force.” Early argued that sort of loss “would have had such a depressing effect upon the country, and would so encourage the enemy as to amount to a very serious, if not fatal, disaster to our cause.”

Adding up all those factors, Early theorized, “will cause the intelligent reader to wonder, not why I failed to take Washington, but why I had the audacity to approach it as I did, with the small force under my command.”

Early repeated that argument for decades in countless newspaper and magazine articles, speeches, letters to newspaper editors and in his two war memoirs, A Memoir of the Last Year of the War for Independence in the Confederate States of America and Autobiographical Sketch and Narrative of the War Between the States. The latter book, which Early published in 1866, was the first Civil War memoir written by one of the war’s prominent figures.

Early added a new wrinkle to the story in a letter to the editor that appeared in the December 14, 1874, edition of the Richmond Sentinel: Lee did not ask him to invade Washington. Lee, Early said, “did not expect that I would be able to capture Washington with my small force; his orders were simply to threaten the city.”

The object of his entire four-week campaign, Early said, was not to invade Washington but to influence Grant to send significant numbers of troops away from Richmond and Petersburg. Lee, he said, “would have been gratified if I could have taken Washington, but when I suggested to him I would take it if I could, he remarked that it would hardly be possible to do so….”

Lee, in fact, did stress from the beginning that getting Grant to move troops out of Richmond—along with pushing Hunter out of the Valley—was his main goal on June 13 when he sent Early to Lynchburg. It “was hoped,” Lee wrote to Secretary of War James A. Seddon on July 19, “that by threatening Washington and Baltimore Genl Grant would be compelled either to weaken himself so much for their protection as to afford us an opportunity to attack him, or that he might be induced to attack us.”

Lee also listed several “collateral results” of Early’s mission, primarily “obtaining military stores and supplies.” Lee’s overall assessment of Early’s performance was positive. So “far as the movement was intended to relieve our territory in that section of the enemy, it has up to the present time been successful,” he told Seddon.

President Jefferson Davis also espoused that sentiment. “I have been asked,” he said in a September 23, 1864, speech in Macon, Ga., “why the army sent to the Shenandoah Valley was not sent here? It was because an army of the enemy had penetrated the Valley to the very gates of Lynchburg and General Early was sent to drive them back.”

Early “not only successfully did,” Davis said, “but, crossing the Potomac, came well-nigh capturing Washington itself, and forced Grant to send two corps of his army to protect it.” The Confederate president noted that the enemy had called that action a raid. “If so, Sherman’s march into Georgia is a raid,” Davis said.

Davis believed that Early’s success against Hunter in the Valley, Grant being forced to send troops to Washington, and Early’s move back into the Valley staved off the fall of Richmond in the summer of 1864. “What would prevent them now,” he said, “if Early was withdrawn, penetrating down the valley and putting a complete cordon of men around Richmond?”

Washington Saved, Wallace Redeemed

Although Grant, with Halleck’s endorsement, demoted Wallace after the defeat at Monocacy, the Union Army’s commanding general quickly swung 180 degrees in his opinion of Wallace’s performance. At Grant’s urging—and presumably against Halleck’s wishes—Secretary of War Edwin Stanton moved to reinstate Wallace on July 28, 1864, as the commander of the Middle Department.

In his official report written a year later, Grant said that Wallace, with “a force not sufficient to ensure success” at Monocacy, fought “the enemy nevertheless, and although it resulted in a defeat to our arms, yet it detained the enemy and thereby served to enable General Wright to reach Washington with two divisions of the Six Corps, and the advance of the Nineteenth Corps.”

Grant expanded on his praise for Wallace in his memoir, which he wrote in the early 1880s: “Whether the delay caused by the battle [of Monocacy] amounted to a day or not, General Wallace contributed on this occasion, by the defeat of the troops under him a great benefit to the cause that often falls to the lot of a commander of an equal force to render by means of a victory.” Most historians can agree on the fact that the Battle of Monocacy—the only clear-cut Confederate victory north of the Mason-Dixon Line—did ultimately save Washington from Early’s men.

Changing the Course of the War?

The broader question remains though: Did Monocacy and Early’s subsequent move on the nation’s capital change the course of the Civil War? Adding up all the evidence, a strong case can be made that Wallace’s stand and Early’s rebuff at Washington did just that.

For one thing, delaying Early and preventing him from invading Washington on July 10 when the city was ripe for the taking certainly had an impact—albeit a temporary one—on the contentious 1864 presidential election. “Many in the North saw [Early’s] raid as evidence of northern military mismanagement and the impossibility of ever winning the war,” eminent Civil War historian James McPherson wrote. “It gave a boost to the hopes of northern Peace Democrats—the Copperheads—to gain control of the party and defeat Lincoln’s re-election.”

According to another noted Civil War historian, Gary Gallagher, “Had Wallace failed to intercept Early, [his] Army of the Valley might have fought its way to Washington on July 10.” No one can say exactly what would have happened next, but as Gallagher put it, “it can be said with confidence that Wallace’s troops spared the Lincoln government a potential disaster, and for that reason the battle of the Monocacy must be considered one of the more significant actions of the Civil War.”

It is not at all far-fetched to postulate that Early’s move into the Valley and his sojourn into Maryland actually prevented Grant in June or July 1864 from doing one of two things that could have broken Lee’s back: mounting an all-out assault on Richmond or drawing Lee out of his dug-in position to fight on Grant’s terms. Grant, with Lincoln’s backing, was ready to take some sort of decisive action that he strongly believed would hasten the end of the war.

Before he learned of Early’s move into the Shenandoah and Maryland, Grant “had been planning some important offensive operations in front of Richmond,” his aide-de-camp, Lt. Col. Horace Porter, wrote in his war memoir. But Early’s move into Maryland caused the Union commander “to postpone these and turn his chief attention to Early.”

Grant, Lincoln said in a June 16 speech at the Philadelphia Sanitary Fair, is “in a position from whence he will never be dislodged until Richmond is taken.” Grant “is reported to have said,” Lincoln recounted, “‘I am going through on this line if it takes all summer….’”

Grant himself had boasted on July 5, the day that Early’s troops crossed the Potomac into Maryland, that he had “the bulk of the Rebel Army” besieged in Richmond and “conscious that they cannot stand a single battle outside their fortifications with the Armies confronting them.”

The “last man in the Confederacy is now in the Army,” Grant speculated in a letter written that same day to a friend from his hometown of Galena, Ill., steamboat magnate J. Russell Jones. “They are becoming discouraged, their men deserting, dying and being killed and captured every day. We [lose men, too] but can replace our losses.”

In a telegram Grant wrote to Halleck from City Point four days later, the same day Early fought Wallace at Monocacy, Grant spoke of his desire to complete his assembly of “a large force” outside Richmond by the 20th of that month. The object: to mount “aggressive operations” against Petersburg. But, Grant said, he would be willing to postpone said operations if “the rebel force now North can be captured or destroyed.”

That is essentially what happened. Lee’s bold move in sending Early to the Shenandoah Valley forced Grant to part with the VI and XIX corps—and to put off whatever “aggressive operation” he had envisioned—perhaps a final assault that might have crushed Lee’s army and ended the Civil War sometime in the summer or fall of 1864. At the very least, without Lee’s risky strategic move, chances are that it would not have taken Grant until April 1865 to win the war.

Lee’s “strategy in sending Early down the Shenandoah prolonged the defence of Richmond for nine months,” Thomas L. Livermore, a staff officer for Union Maj. Gen. Andrew Humphreys, wrote after the war. Lee’s move, Livermore said, “led Grant to reduce his force so much that he could not force a conclusion.”

Livermore calculated that the number of able-bodied Union troops arrayed outside Richmond and Petersburg dropped from 137,454 on June 30 to 93,542 on July 31, and ultimately to just 69,206 by August 31. The precipitous fall-off was due to the departure of the VI Corps to Washington, but also to casualties, illness and the fact that many Union soldiers simply went home when their terms of enlistment ended.

Those factors reduced the number of Grant’s troops around Richmond and Petersburg “by 25 percent in August,” Livermore said, a number that “remained for a long time below the danger line for a besieging force.”

The fight at Monocacy has come to be known as “the battle that saved Washington.” It was. It also very possibly was the event that played the most pivotal role in the series of actions that began with Lee’s June 12, 1864, order to send Early to the Valley, and ended a month later when Early escaped back into Virginia. That series prolonged the course of the Civil War by as many as nine long months, but it also ended with Washington, D.C., a capital city that was militarily and politically vulnerable, safe in Northern hands and the Union war effort spared from a potential disaster.

This article was written by Marc Leepson and originally published in the August 2007 issue of Civil War Times Magazine. For more great articles, subscribe to Civil War Times magazine today!