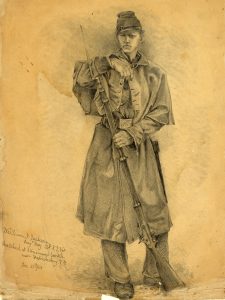

Lieutenant Octavius Wiggins of Company E, 37th North Carolina, peered out across Arthur’s Swamp in the pre-dawn darkness of Sunday, April 2, 1865. He was searching for the masses of assaulting Federal soldiers that he and his fellow members of Brigadier General James Lane’s Brigade expected every morning to face along the lines south of Petersburg. Suddenly a few rifle shots from Rebel pickets broke the morning silence, followed by ‘one full, deep, mighty cheer,’ alerting Wiggins that this would be the morning.

The thin line of Confederate soldiers in the breastworks offered what resistance they could provide before they were overwhelmed. One of the Federal soldiers pointed the muzzle of his rifled musket at Wiggins and pulled the trigger. The blast blew powder into the lieutenant’s face, nearly destroying his eyes and knocking him senseless upon the ground.For nine long, weary months, a set of formidable field fortifications and an obstinate foe had kept the Army of the Potomac out of Petersburg, Va., the capture of which would have made the Confederate capital and industrial center of Richmond indefensible, hastening the end of the war. Southern soldiers fought valiantly during those nine months. Each time the Federal army sought to move westward in an attempt to cut the Rebel supply lines, portions of the Confederate army battled back. Yet the numerically superior Federals were able to continually lengthen their lines, stretching the Confederate defenders painfully thin.

In March 1865, General Robert E. Lee recognized that if other Federal forces in the Shenandoah Valley and North Carolina united with the Army of the Potomac, Richmond and Petersburg could not be held. The Confederate commander chose to strike first, and on March 25 attacked Fort Stedman, to the east of Petersburg. The assault met with early success, but the Confederates were later routed from their prize by Federal reinforcements. Lee’s only option was to retreat, and he waited for supplies and dry roads for his army.

On March 24, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, the overall Union commander, had issued orders for an offensive he believed would end the war. Infantry from the Army of the Potomac and cavalry from the Shenandoah Valley were to move west of Petersburg and destroy the South Side and Danville railroads. By 5 p.m. on March 28, the Federal cavalry was at Dinwiddie Court House, southwest of Petersburg, with the infantry moving in early the following morning. Lee pulled men from the front lines and his sole remaining reserves and sent them west to confront this force.

Portions of the two opposing forces clashed early in the afternoon around the Lewis farm, leaving the Federals in control of the field at the end of March 29. Meanwhile, the infantry that Lee had sent west arrived that evening and went into position at Five Forks.

Two different assaults followed on March 31. Four Confederate brigades attacked two Federal divisions on the White Oak Road, initially driving them back in confusion. By early afternoon, however, the Federal counterattack had pushed the Confederates back to their works.

The other Confederate attack was on the Federals at Dinwiddie Court House, and followed a similar pattern. The Rebels again made early gains, but these were erased as Federal reinforcements arrived overnight and forced the Confederates to fall back to Five Forks. A Union attack on Five Forks on April 1 pushed the Confederates out of their entrenchments and opened the way for a grand assault on the Confederate lines.

In the last weeks of March, the veterans of the 37th North Carolina had been one of the many Southern regiments juggled among the trenches south of Petersburg. On March 24, they, along with the other three regiments in Lane’s Brigade, had been placed in support of the attack on Fort Stedman. They were back in their old trenches the following day, and skirmished with the Federals that evening. Another skirmish followed on March 27, and on the 29th Brig. Gen. Samuel McGowan’s brigade, on the right of Lane’s Brigade, had been pulled out of the trenches and sent to help with the attack toward Dinwiddie Court House. The Tar Heels were forced to extend their position. Their division commander, Maj. Gen. Cadmus Wilcox, estimated that the distance between each soldier was 10 feet. The veteran soldiers hoped that the Federal generals would focus on the action at Dinwiddie and not on their lean lines.

On the 30th, anticipation gripped the Federal troops of the VI Corps across from Lane’s Confederates. They loaded their baggage wagons and harnessed their mules, while officers had their horses saddled, ready to step off toward the imposing Confederate lines at a moment’s notice. One brigade commander thought that the next day might ‘be a day of carnage & blood between the contending armies around Richmond.’ The Federal regiments were often up at 4 a.m., prepared to meet any possible dawn assault from the Confederates. Orders went out to the VI Corps to stage a dawn assault on April 1.’All the regimental commanders were ordered to report to Brigade headquarters where we were told that the 6th Corps must attack Petersburg,’ wrote Elisha Hunt Rhodes. ‘We must not fail….We must take the enemy’s work[s] no matter what it cost. We returned to our Regiments in a solemn frame of mind and made preparations.’

But weather conditions prevented the Union troops from detecting the withdrawal of McGowan’s Brigade, and by the early evening hours, the attack was called off. Later that night, word that the Confederates had indeed been on the move reached the VI Corps commander, Maj. Gen. Horatio G. Wright. He requested permission to proceed with the attack. Wright lacked sufficient time to get the troops into position before dawn, however, and the Federal soldiers returned to their rain-sodden camps.

All along the Confederate lines there was a sense of despair on April 1. One soldier wrote of ‘a feeling of unrest and apprehension, not only among the individuals, but even the animals….I have no recollection of having spent a more thoroughly disagreeable day.’

Despite the bad weather, Grant was invigorated by the success of the Federal attack at Five Forks on the 1st. He sent out new orders for a general assault against the Confederate entrenchments on April 2.

Wright’s VI Corps was again chosen to spearhead the attack. Members of the corps had detected a vulnerable point alongthe Confederate lines, and senior Union officers, including Wright and Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, examined the area several times. They observed that Arthur’s Swamp, a sluggish morass that extended from the Union lines to near the Boisseau home, was fed by a number of tributaries that caused breaks in the Confederate lines. One of the ravines was only 50 or 60 feet wide at the place where it intersected the Confederate lines, but it extended into a flat marsh nearer the Union picket lines.

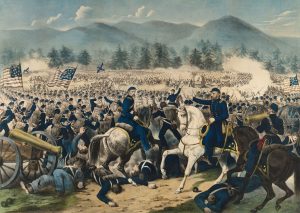

Due to the nature of the woody, marshy ground, the Confederates had not built fortifications across the depression but had placed artillery on either side of it. Throughout the winter, McGowan’s infantry was posted along this section of the line. Lane’s Brigade of North Carolinians had replaced McGowan only days prior to the planned April 2 Federal assault.Orders went out to the VI Corps: ‘You will assault the enemy’s works in your front at 4 a.m. to-morrow morning.’ Major General George W. Getty’s division was assigned to lead the attack. His right was supported by the division of Brig. Gen. Frank Wheaton and his left by the division of Brig. Gen. Truman Seymour, both of which were positioned in echelon. The regiments in each brigade were stacked behind one another, providing a nar-row front but great depth.

Wright’s assaulting force consisted of some 14,000 soldiers. Officers were instructed to leave their horses behind, and the men in the leading ranks were to leave the priming caps off their muskets, relying on bayonets only. One brigade commander told his line officers: ‘We are going to have a hell of a fight at early daylight….I want you fellows to simply tell your first sergeant to have the men fall in ready to march…at 1 o’clock a.m. Now you can go to your quarters and if any of you have anything to say to your folks, wives or sweethearts make your story short and get what sleep you can for hell will be tapped in the morning.’

Federal artillery — some 150 guns — opened fire at 10 p.m. on the opposing entrenchments. One Confederate general recalled ‘an almost incessant cannonade, solid shot and shell whizzing through the air and bursting in every direction, at times equal in brilliancy to a vivid meteoric display.’ General Grant hoped the shelling would convince the Rebels to abandon their fortifications, and thus save lives. The Confederates returned the fire, however, making it seem to one Federal as if ‘the devils in hell were fighting in the air.’

Federal soldiers of the VI Corps began moving into position about the same time the long-range duel began. Artillery fire began to slacken by 1 a.m., as more Federals shifted into line behind their pickets and strained to conceal their movements from the Confederate sentinels.

Rebel pickets along the front lines opened fire, striking members of the assaulting force — who were not allowed to return fire, lest they expose their attack. Some of the Federals blamed their own pickets for bringing on the brisk firefight; they thought it was an attempt to mask the sounds of thousands of moving men. Others believed that the Confederates had detected the Federals moving into position and were attempting to provoke the main body into firing and giving away their location.

Brigadier General Lewis Grant’s brigade of Vermonters took the lead in the attack. They were positioned on the left of Getty’s division, with their left resting on the edge of the ravine. Grant had been wounded in the head during the skirmish between the pickets, and leadership of the brigade devolved to Colonel Amasa Tracy of the 2nd Vermont. Tracy commanded six regiments. To his right was the brigade of Colonel Thomas Hyde, composed of men from Maine, New York and Pennsylvania. Colonel James Warner’s brigade of Pennsylvanians was to the right of Hyde.

Farther to the right of Getty was Wheaton’s division, with brigades led by Colonels Oliver Edwards, William Pen-rose and Joseph Hamblin. Across Arthur’s Swamp, to the left of the Vermont Brigade, was Seymour’s division. The right of Colonel J. Warren Keifer’s brigade rested in the swamp, and to his left was the brigade of Colonel William Truex. Accompanying the infantry were three batteries of artillery, one for each division, along with a group of 20 volunteer artillerymen that hoped to turn captured Rebel guns on their former owners.

The Confederate task of guarding the area around Arthur’s Swamp fell to James Lane’s North Carolina Brigade. Lane positioned the 28th North Carolina on his right. The 37th North Carolina came next, to the left of the 28th, with the ravine of one of the tributaries of Arthur’s Swamp between the two forces. To the left of the 37th came the 18th North Carolina, and the 33rd North Carolina was on the brigade’s left. To the left of the 33rd was a brigade of Georgians under Brig. Gen. Edward L. Thomas, and to Lane’s right were two regiments of Brig. Gen. William MacRae’s Brigade: the 11th and 52nd North Carolina, under the command of Colonel Eric Erson.

Several artillery emplacements strengthened the Confederate line, but Lane’s four regiments probably numbered no more than 1,100 men. His fifth regiment, the 7th North Carolina, had recently been detached and sent to its home state.

The Federals waited in the darkness, miserable and solemn. Not only was the earth wet and the weather cold, but the early morning hours between when they went into position and when they were called to battle gave many hours to think of nothing but the unpleasant task at hand. All too often they had tried frontal attacks where the assaulting force gained nothing and suffered devastating losses.

Although the attack was slated to begin at 4 a.m., given the total darkness that pervaded the area the Federals had to cross, General Wright postponed the assault until 4:40 a.m. Wright thought that by then ‘it had become light enough for the men to see to step, though nothing was discernible beyond a few yards’ distance.’ A cannon in Fort Fisher, belonging to the 3rd Vermont Battery, broke the silence, and the Federal infantry stepped off.

Alert Confederate pickets produced a weak and scattering volley and attempted to make for the main Confederate lines. The Federals gave a cheer that, combined with the rifle fire from the pickets, warned the main Confederate line of their approach.

The 5th Vermont, leading the attack, advanced through the pickets, capturing many who were not quick enough to escape. The Vermonters were just about to reach the obstructions when, remembered a Yank, a ‘well-directed musketry fire from the front and artillery fire from the forts on either hand’ tore into their ranks, demoralizing the Federal soldiers and almost bringing an end to the assault.

One Union captain recalled that many of the men in the brigade ‘refused to advance further than the rebel picket line. I never had to strike men with my saber before to make them advance but that day I did [strike] a great many of them and in earnest too, as hard as I could with the flat of my sword….’ Thanks to the work of the officers, the stalled brigade regained its momentum and proceeded with its attack.

Federal soldiers soon encountered a line (possibly two) of abatis — trees that had been felled by the Confederates with their branches pointing toward the Union lines. The Rebels had sharpened the branches, presenting a formidable challenge for an attacking force to pass. During the assault, members of the Federal army detailed as ‘pioneers’ advanced with axes. As the attackers advanced and came upon the abatis, they called for their pioneers, who went to work chopping up and clearing the downed trees. One Yankee soldier recalled that while he was working,’seven of our Pioneer comrades were killed in that one place.’

Captain Charles G. Gould of the 5th Vermont was the first Federal inside the works. He had found a weak place in the abatis and led the way through the ditch and up the parapet into the Confederate lines, followed by several of his men. As soon as Gould gained the lines, a Confederate pointed his rifle at the captain and pulled the trigger. The gun misfired, but a second Rebel bayoneted Gould in the mouth, and the blade passed under his lip and emerged at the lower part of the jaw near his neck. Gould thrust his saber through that Tar Heel, killing him. Another Confederate slashed Gould on the head with a sword. Gould was grabbed, hands partially ripping off his overcoat. Before he could struggle free from his assailants, a second bayonet was thrust at the officer, entering his spine and penetrating nearly to the spinal cord.

The captain attempted to crawl back over the works, and one of his own men, Corporal Henry Recor of Company A, rescued him, although Recor was also wounded while dragging Gould into the ditch. Gould staggered toward the main Federal lines, seeking medical aid and reinforcements for his Vermonters. Captain Gould survived his wounds and was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions.

More Federal soldiers poured into the fortifications and fought hand to hand with the Tar Heels. Close-quarters fighting took place when several members of the 37th Massachusetts of Edwards’ brigade spied the colors of the 37th North Carolina. Lieutenant William Waterman, Corporals Luther Tanner and Richard Welch, and Private Michael Kelly, all of Company E, rushed toward the Confederate color-bearer.

The ensuing melee left Lieutenant Waterman wounded in the wrist. Corporal Tanner was killed, as was Private Kelly, but not before he bayoneted a Tar Heel who was trying to kill the 37th Massachusetts’ regimental commander. Corporal Welch knocked down the color-bearer of the 37th North Carolina and seized the banner. Welch was also awarded the Medal of Honor for capturing that flag.

‘I was driven from the works,’ recorded the 37th North Carolina’s regimental com-mander, Major Jackson L. Bost. ‘[Our] line…was broken and the enemy were filling down in the rear of our works toward Petersburg. I had to fall back directly to the rear and formed a skirmish line as best I could to keep the enemy from advancing too fast in our rear.’ Major Bost lost approximately two-thirds of his regiment. Among the dead were three of his company commanders: Captains William T. Nicholson, Company E; John B. Petty, Company F; and Daniel L. Hudson, Company G. Sergeant Yates Lacy of the 5th Wisconsin recalled that he ‘did a little artistic bayonet work’ and that ‘the Johnny that he interviewed passed on to sweet subsequently.’

Other Confederates ‘threw down their guns and surrendered,’ said Elisha Hunt Rhodes. ‘They shouted `Don’t fire, Yanks!’ and I ordered them to go to the rear, which they did on the run.’ Union troops captured well over 100 veteran soldiers of the 37th North Carolina, including several who were wounded.

Rhodes’ men had advanced with their rifles uncapped. Now that they had gained the Confederate works, he ordered them to prime, and a volley was sent after the retreating Tar Heels.

Elsewhere along Lane’s line, his other regiments were collapsing. The attack of Keifer’s brigade, to the left of the Vermont brigade across Arthur’s Swamp, focused on the 28th North Carolina. Keifer had learned of ‘A narrow opening, just wide enough for a wagon to pass through,’ along the Confederate lines to the front of his brigade. He ordered the 6th Maryland, in the center of his brigade, to exploit this opening, holding their fire until they were within the works, when they would ‘open on the Confederates…taking them in the flank, and, if possible, drive them out and thus leave for our troops little resistance in gaining an entrance over the ramparts.’ After navigating through the Confederate pickets and abatis, the Marylanders did gain the Confederate works.

Major Edward Hale, Lane’s assistant adjutant general, on seeing his men coming over the earthworks ahead of the attack, ‘remarked to someone `Why, there are the skirmishers, drive in,’ & called out to know how near behind the enemy were. Just at the moment I observed a stand of colors in the work[s] & the person in command ordered his followers to fire.’ The 28th North Carolina was flanked on the right, and forced to fall back toward the Boydton Plank Road.

The 18th North Carolina, to the left of the 37th North Carolina, suffered the same fate. Federals from Penrose’s New Jersey brigade and Edwards’ mixed brigade of men from Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island and Wisconsin struck the 18th North Carolina with overwhelming force.

Major Augustus Fay of the 40th New Jersey shot the color-bearer of the 18th. Another member of the 40th New Jersey, Private Frank Fesq, retrieved the flag and was later awarded the Medal of Honor for the deed. The 18th North Carolina fell back and attempted to establish a new line, but the troops were soon driven eastward toward Petersburg and the Confederates’ Fort Gregg. (Both the Federal and the Confederte armies had bastions called Fort Gregg at Petersburg.) The 33rd North Carolina was soon forced back toward the inner works as well. Once inside the Confederate works, the Federals began to spread out in all directions.

General Lane sent Lieutenant George Snow of the 33rd North Carolina back to division headquarters with word of the breakthrough. Wilcox gathered together remnants of Lane’s and Thomas’ brigades. The 600 men were ordered forward in a counterattack that allowed Lane and Thomas to recapture two cannons and reoccupy a portion of the lost breastworks. They established a new line perpendicular to the Confederate fortifications.

Surviving members of the 37th North Carolina, along with other soldiers and officers of Lane’s and Thomas’ brigades, retreated into Forts Gregg and Whitworth. There, they held the Federals at bay long enough for Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s corps to stabilize the lines and allow the Confederates an orderly withdrawal during the evening hours.

Thirty minutes passed from the time the assault began before General Wright reported to Meade that his corps had ‘carried the works in front and to the left of the Jones house.’ Meade sent a congratulatory reply to Wright and shared the good tidings with Grant, who passed them on to Abraham Lincoln. Many of the Federals ‘were perfectly wild with delight at their success in this grand assault,’ wrote one division commander.

A fellow soldier, a sergeant in the 14th New Jersey, thought ‘the charge of Major-Gen. Wright’s veterans under cover of the darkness and mist, preceding the break of day, will forever live in history as one of the grandest and most sublime actions of the war.’ Even General Grant referred to the action among ‘the brightest day[s] in the history of the war.’ Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia were forced to abandon Petersburg and Richmond on the night of April 2, and just a few days later surrendered at Appomattox Court House. Other Confederate armies were also forced to capitulate over the next few weeks, and the war, after four long years, ended.

What became of Lieutenant Octavius Wiggins? After he was knocked to the ground by the blast of the Federal rifle, he was captured and taken to the rear. He found fellow members of the 37th North Carolina behind the lines, and they commenced to pick the tiny grains of powder out of his face. Wiggins and the other Confederate prisoners were taken to City Point, Va., where they boarded a steamer for Washington, D.C. There, the officers were placed on a train bound for Johnson’s Island in Ohio. During the night, Wiggins, wearing clothes made from an old gray shawl, jumped out of a window of the car he was riding in and escaped.

He cut off his buttons from his coat and vest, ‘and substituting wooden pegs, he was in perfect disguise and passed as a laborer, working a day or so at one place, then moving further south,’ he remembered. Once he reached Baltimore, he took a steamer to Richmond, but was ‘too late to do any more fighting[,] for General Lee had surrendered.’

This article was written by Michael C. Hardy and originally appeared in the March 2005 issue of America’s Civil War. Tar Heel Michael Hardy is the author of The Thirty-seventh North Carolina Troops: Tar Heels in the Army of Northern Virginia. In addition to his book, for further reading he recommends A. Wilson Greene’s Breaking the Backbone of the Rebellion.