Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln’s Legacy, by David O. Stewart, Simon and Schuster, 2009.

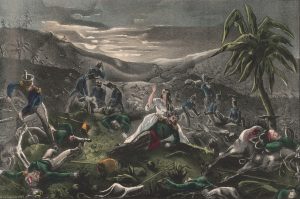

Fulfilling the promise of the Emancipation Proclamation, Congress ratified the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery in December 1865. In the South, however, the amendment proved to be a hollow measure. The former Confederate states adopted laws that effectively returned recently freed slaves to bondage on the slimmest of pretexts, and the small Federal occupying army in the region couldn’t prevent widespread violence against African Americans. It didn’t help that in the White House there was no sympathy for the plight of the freedmen. President Andrew Johnson strove to unconditionally reintegrate the seceded states and relegate to them the authority to decide upon black suffrage, but the Radical Republicans—the dominant block in Congress—wanted to punish the South and guarantee the rights of its black population. A national crisis in the wake of the Civil War was inevitable.

Fulfilling the promise of the Emancipation Proclamation, Congress ratified the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery in December 1865. In the South, however, the amendment proved to be a hollow measure. The former Confederate states adopted laws that effectively returned recently freed slaves to bondage on the slimmest of pretexts, and the small Federal occupying army in the region couldn’t prevent widespread violence against African Americans. It didn’t help that in the White House there was no sympathy for the plight of the freedmen. President Andrew Johnson strove to unconditionally reintegrate the seceded states and relegate to them the authority to decide upon black suffrage, but the Radical Republicans—the dominant block in Congress—wanted to punish the South and guarantee the rights of its black population. A national crisis in the wake of the Civil War was inevitable.

Johnson not only vetoed the Freedman’s Bureau Bill and civil rights acts, he also opposed the 14th Amendment. Congress struck back at him with the Tenure of Office Act, which prohibited the president from dismissing cabinet members without congressional consent. Johnson tested the measure by firing Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, who supported Radical views. But Stanton refused to leave office, and the House brought impeachment charges against Johnson in 1866. In a Senate trial decided by one vote, the president was acquitted.

Impeached, David O. Stewart’s new book, brilliantly examines the heated passions and sordid politics surrounding the impeachment crisis. Stewart demonstrates conclusively that, contrary to popular perception, Johnson abandoned Lincoln’s legacy—and it was Thaddeus Stevens and the Radical Republicans who did all they could to preserve it.

Stewart’s meticulous research in untapped primary sources suggests new and compelling conclusions about the proceedings in the case. Among these is the strong possibility that the vote of Senator Edmund Ross, which saved Johnson, had been bought. At a minimum, Stewart indicates Ross and many other senators voted less from ideals than considerations of personal gain. To his credit, he does not go beyond the bounds of evidence into mere speculation.

Although Stewart acknowledges that much of the evidence he presents is circumstantial, it is difficult not to conclude that Johnson’s surrogates were knee-deep in dirty money.

The book also examines how some of the leading Northern figures of the war responded to the moral and political issues that defined early Reconstruction, including cabinet secretaries Gideon Welles and William Seward; Generals Grant, Sherman and Sheridan; and in particular former generals cum Congressmen Benjamin Butler and John Logan.

Johnson’s standoff with Stanton and Congress created real fears of renewed military conflict. His attempt to fire Stanton so profoundly frightened Union veterans that Congressman Logan, commander in chief of the Grand Army of the Republic, issued a secret call for the organization to be ready to defend Congress from violent usurpation.

As a distinguished attorney who defended the impeachment trial of a Mississippi judge in the U.S. Senate and has argued appeals before the Supreme Court, Stewart is well qualified to write authoritatively on the Johnson impeachment. The same narrative skills that characterized his The Summer of 1787: The Men Who Invented the Constitution enable Stewart to make the murky underpinnings of impeachment comprehensible.