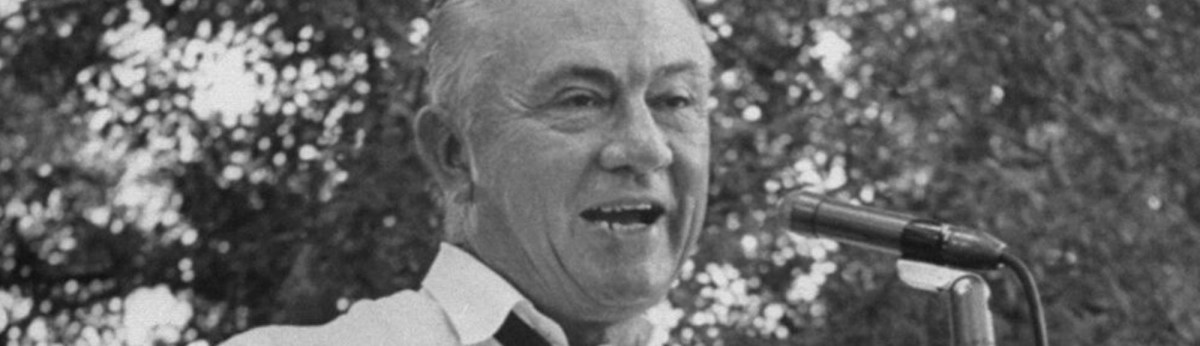

Texas radio showman talked his way into the U.S. Senate

W. LEE “PAPPY” O’Daniel started out selling flour but ended up selling himself, riding the radiowaves to fortune, fame, the Texas governor’s mansion, and the United States Senate. He was the first celebrity of the mass media age to win high office—but not the last.

Raised in Kansas, O’Daniel was a go-getter and didn’t stay long on the farm. After high school, he opened a restaurant, sold it, and used the money to enroll in business college. Finishing a two-year curriculum in eight months, he took a job at a flour-milling firm. But he was a go-getter and didn’t stay long at the mill, leaving to start his own flour company. When that operation went bust, he took a job at another flour company, then another. In 1925, at age 35, he moved to Fort Worth, Texas, to sell Light Crust Flour. He possessed the gift of gab and he knew how to sell flour, touting Light Crust’s “high protein content.” He began managing the company’s radio advertising.

Six years later, a Fort Worth radio announcer suggested that Light Crust Flour sponsor a daily 15-minute show starring a local band with a hot fiddler, name of Bob Wills. Radio was still new and O’Daniel was skeptical, but he agreed to sponsor and try producing the show on KFJZ. He renamed the band the Light Crust Doughboys, and started writing songs for the group, as well as the program’s scripts. Soon, he was hosting the show. In those days radio announcers spoke as if addressing a crowded auditorium but O’Daniel talked like he was sitting at your kitchen table. He sounded like a big brother, a trusted uncle, an old friend.

“How do you do, ladies and gentlemen, and hello there, boys and girls,” he’d drawl in his rich baritone at the start of every show. “This is W. Lee O’Daniel speaking.” With the Doughboys playing softly in the background, he talked about the beauty of Texas, the glory of Jesus, and the sanctity of motherhood. Mothers bought flour and Pappy knew how to butter them up. “Hello there, mother, you little sweetheart,” he’d say. “How in the world are you, anyway, you little bundle of sweetness?”

He wrote songs about motherhood and taught them to the Doughboys by whistling the melodies at the musicians. He called one song “The Boy Who Never Grew Too Old to Comb His Mother’s Hair”; another tune began “Mother, you fashioned me/bore me and rationed me…” He wrote songs about Texas and cowboys and a sentimental ditty about an old horse. Naturally, the Doughboys also sang with passion about Light Crust flour.

People loved the Light Crust Doughboys show, which drew more listeners than any radio show in Texas. The show went on the air at 12:30, when farm families gathered in their kitchens for lunch. Light Crust flour sales soared. O’Daniel became famous and so did his slogan, “Please Pass the Biscuits, Pappy!” By the mid-1930s, “Pappy O’Daniel” had become a household name across Texas.

But Pappy was a go-getter and he didn’t stay long at Light Crust. In 1935, he founded his own company, selling “Hillbilly Flour.” He moved the show to WBAP, fired the Doughboys, and hired a band he named the Hillbilly Boys. He designed his company’s flour sacks; on one side a Hillbilly Boy mothers could sew into a doll, and other Pappy O’Daniel’s verse:

HILLBILLY Music “on the air”

HILLBILLY Flour everywhere;

It tickles your feet—it tickles your tongue

Wherever you go, its praises are sung.

Pappy got rich. He invested in real estate and got richer. On WBAP, he played the good ol’ boy. Off the air, he hobnobbed with fellow moguls—oil barons and ranchers. In 1938, rich pals suggested a new marketing scheme for Pappy: Why don’t you run for governor?

Pappy pondered the idea. He didn’t know much about politics—he wasn’t even registered to vote—but he knew how to sell himself. He figured that running for governor would be a terrific way to sell flour.

On Palm Sunday, 1938, Pappy told his listeners a blind man had written saying Texas needed to kick out the professional politicians and elect a governor who was honest and trustworthy, a good Christian—somebody like Pappy O’Daniel. He asked: Should I run for governor?

Fan mail inundated him. He reported that 54,499 people had urged him to run; four objected. On May 1, 1938, Pappy announced on the air that he was entering the Democratic primary for governor. His platform was the Ten Commandments, he said, and his campaign slogan was “Pass the Biscuits, Pappy!”

Fan mail inundated him. He reported that 54,499 people had urged him to run; four objected. On May 1, 1938, Pappy announced on the air that he was entering the Democratic primary for governor. His platform was the Ten Commandments, he said, and his campaign slogan was “Pass the Biscuits, Pappy!”

Smart types scoffed. Politicians and reporters rolled their eyes and reminded each other that O’Daniel had no political experience and no knowledge of the issues—and didn’t seem to care. He was an entertainer, a showman.

That June, six weeks before the primary, Pappy headed out in a red circus wagon, accompanied by his wife, Merle, and their kids and the Hillbilly Boys. His first campaign stop was Waco, where more than 20,000 people were waiting to see him. In Houston, 26,000 people greeted Pappy—the biggest political gathering Texas had ever seen.

Pappy O’Daniel traveled 20,000 miles. Rallies all over Texas each began with the Hillbilly Boys singing Pappy’s “My Million Dollar Smile.” Pappy would stride onstage, a pudgy man with slicked-back hair and a smile that did seem quite rich. “Hello, friends!” he’d say. “This is W. Lee O’Daniel, the next governor of Texas!”

He’d sing, tout Hillbilly Flour, quote scripture, and declare he was fed up with “crooked politics” and “scheming professional politicians.” He promised to pay every Texan over 65 a $30-a-month pension. He didn’t say how he’d fund those pensions, preferring to sell the idea singing lyrics he’d written to the tune of “Let Me Call You Sweetheart”—“Thirty Bucks for Mama.”

Smart types scoffed. Politicians and reporters said Pappy’s crowds came for the circus. But battered Texans yearned for something new. In the Democratic primary, against 11 rivals, Pappy got 51 percent, taking the nomination in a state where Republicans didn’t count.

In January 1939, 100,000 Texans came to see Pappy sworn in. He soon was broadcasting his show from the governor’s mansion. He found the Hillbilly Boys state jobs, making one a colonel in the Texas National Guard. He blasted legislators for defeating his pension plan because he refused to raise taxes to pay for it. He backed an amendment to the Texas Constitution forever limiting taxes on oil and gas. That measure, too, failed to pass.

“Almost totally ignorant of the mechanics of government, O’Daniel proved unwilling to make even a pretense of learning, passing off the most serious problems with a quip,” wrote historian Robert Caro. “He offered few significant programs in any area, preferring to submit legislation that he knew could not possibly pass and then blame the legislature for not passing it.”

Running for reelection in 1940, Pappy traded 1938’s optimism for tirades about “poison-pen editors” and “pin-headed legislators” and “communist labor leader racketeers.” He won, beating six opponents in the Democratic primary.

But he tired of governing. He was a go-getter and didn’t stay long in Austin. In April 1941, U.S. Senator Morris Sheppard (D-Texas) died. Calling an election for June, Pappy ran. He eked out a win against 28 rivals, beating Rep. Lyndon B. Johnson (D-Texas), the runner-up, by 1,311 votes. A year later, in another close one, Pappy won a full term damning opponents as “skunks, buzzards, wolves, thugs, termites, pirates, outlaws, racketeers, and hatchet brigades.”

As senator he scorned the “communist-controlled New Deal,” demanding “restoration of the supremacy of the white race.” He retired in 1949 and founded an insurance company in Texas. But he missed the spotlight. In 1956 and 1958, he ran for governor, losing both times.

“Hello, there, I’m W. Lee O’Daniel and I’m running for governor,” Pappy greeted a group of cowboys eating in a Fort Stockton café in 1958.

“Pappy O’Daniel?” a cowboy replied. “I thought he was dead.”

Pappy O’Daniel died in 1969, but he lives on as the inspiration for Charles Durning’s character in the Coen brothers movie O Brother, Where Art Thou? And he blazed a path other entertainers took, including Ronald Reagan, Sonny Bono, Jesse Ventura, Al Franken, and, of course, President Donald J. Trump.