Image courtesy of WGBH

Image courtesy of WGBH

Thirty years after the former 13 American colonies abandoned the Articles of Confederation “in order to form a more perfect Union” and “secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity,” slavery still existed within the United States. Its eventual demise was assumed to be not far beyond the horizon; every Northern state had abolished slavery, and Congress had prohibited it in the Northwest Territories. But the development of the cotton gin made possible more efficient methods of processing cotton fiber. Increased demand for cotton required ever-greater growing areas, necessitating increased use of slave labor in the South; Northern textile mills also depended upon those Southern slaves to keep cotton fibers flowing northward. By 1830, slaves represented the largest financial asset in American society—more than all the manufacturing and transportation industries put together. Only the land itself surpassed the combined worth of slave property.

Those observations come early in The Abolitionists, a new, three-part series from American Experience on PBS, directed by Rob Rapley (Freedom Riders, The Supreme Court, Wyatt Earp). The first installment of The Abolitionists airs Tuesday, January 8, from 9:00 to 10:00 pm ET. The second and third parts follow on January 15 and 22. As always, check your local PBS listings for times in your area.

The series explores the lives of five of the most prominent voices of the abolition movement, but more importantly it examines the rise, fracturing, decline, and resurgence of what was arguably the most important social crusade in all of American history. It tells its story in a compelling manner—this reviewer watched all three episodes back to back and was never bored—and leaves viewers with a deeper understanding of the conflicting approaches to ending slavery in America.

The format is well-trod ground: narration while old photos and documents fade in and out; dramatic re-enactments of some key events; commentary from a few historians. This recipe has proven successful many times, and it works particularly well in this series. The “talking head” sequences are well-spaced throughout instead of dominating the production, and what makes The Abolitionists so watchable is the acting by those portraying historic figures, including Angelina Grimke (played by Jeanine Serralles), Frederick Douglass (Richard Brooks), William Lloyd Garrison (Neal Huff), John Brown (T. Ryder Smith), and Harriet Beecher Stowe (Kate Lyn Sheil).

The five represent a disparate group. Grimke was born into a slave-owning family of the South Carolina aristocracy, but she leaves the South because of her opposition to slavery. Douglass was a slave who escaped to freedom and became an inspiring figure for both white abolitionists and blacks who hoped to find freedom and / or rise in society. Garrison found his spiritual fulfillment as publisher of the most prominent abolition newspaper, The Liberator. Unlike Garrison, who staunchly advocated non-violent evangelism as the means of ending slavery (lead slave owners to redemption by getting them to renounce the peculiar institution), John Brown became the face of violent opposition to slavery, a saintly martyr to abolitionists but the devil incarnate to slave owners and others who opposed the “fanaticism” of abolition. It was Harriet Beecher Stowe, however, who discovered the way to swell the ranks of abolitionists was not through logical appeals nor violence but by touching their heartstrings, as she did with Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Viewers whose knowledge of the abolition movement is limited to the surface material they learned in school will likely be surprised by some of the information presented in this series. Northern mobs threatened Garrison’s life, and in Philadelphia, the City of Brotherly Love, a mob set fire to a prominent building the night after Angelina Grimke spoke within it. White firemen stood by, watching it burn.

While Uncle Tom’s Cabin is well known, many Americans are unfamiliar with Slavery As It Is, a powerful compilation of slave abuse taken from the words of slave owners themselves (“I burnt her with a hot iron.”) published by Grimke and her husband. Perhaps the information that will most surprise viewers is that within the space of five months President Abraham Lincoln declared the Civil War was not about slavery; he suggested all blacks should leave the U.S., because he despaired of them ever having equality here; proposed the Emancipation Proclamation freeing all slaves in rebel territory; and offered a peace plan to Congress that would have guaranteed Southerners they could retain their slaves until 1900 if they would lay down their arms.

The confusing signals coming from the president led Garrison to deplore Lincoln’s association with “the white trash of Kentucky,” which had left him with “nothing noble or uplifting in his character.” Douglass went even further, declaring Lincoln was “a genuine representative of American prejudice and Negro hatred.” Rather curiously, the program never mentions that, as a legislator in Illinois, Lincoln voted with the majority to condemn the agitation of abolition societies, then promptly offered a bill mollifying the language of the previous bill.

There is also not much by way of explaining why slavery was so ingrained in America, especially in the South, beyond the economic considerations. The focus of the program admittedly is the abolitionists, but spending a little more time discussing the political considerations, religious and social beliefs that underpinned the peculiar institution would have enhanced viewers’ understanding of why so many Americans, South and North, opposed abolition so intensely.

Apart from those points, The Abolitionists succeeds in telling the story of the abolition movement and the gradual shifts in public opinion that ultimately allowed abolitionists to achieve their goal of freedom for all Americans. Highly recommended.

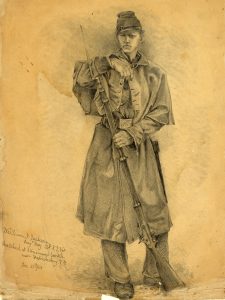

John Brown (T. Ryder Smith) tries to persuade Frederick Douglass (Richard Brooks) to join his planned assault on Harper’s Ferry as Shields Green (Thomas Coleman) looks on. Courtesy WGBH and Antony Platt.

John Brown (T. Ryder Smith) tries to persuade Frederick Douglass (Richard Brooks) to join his planned assault on Harper’s Ferry as Shields Green (Thomas Coleman) looks on. Courtesy WGBH and Antony Platt.