In northern France in 1918 this humble American rifleman from rural Tennessee set aside his boyhood ideals to wage a one-man battle.

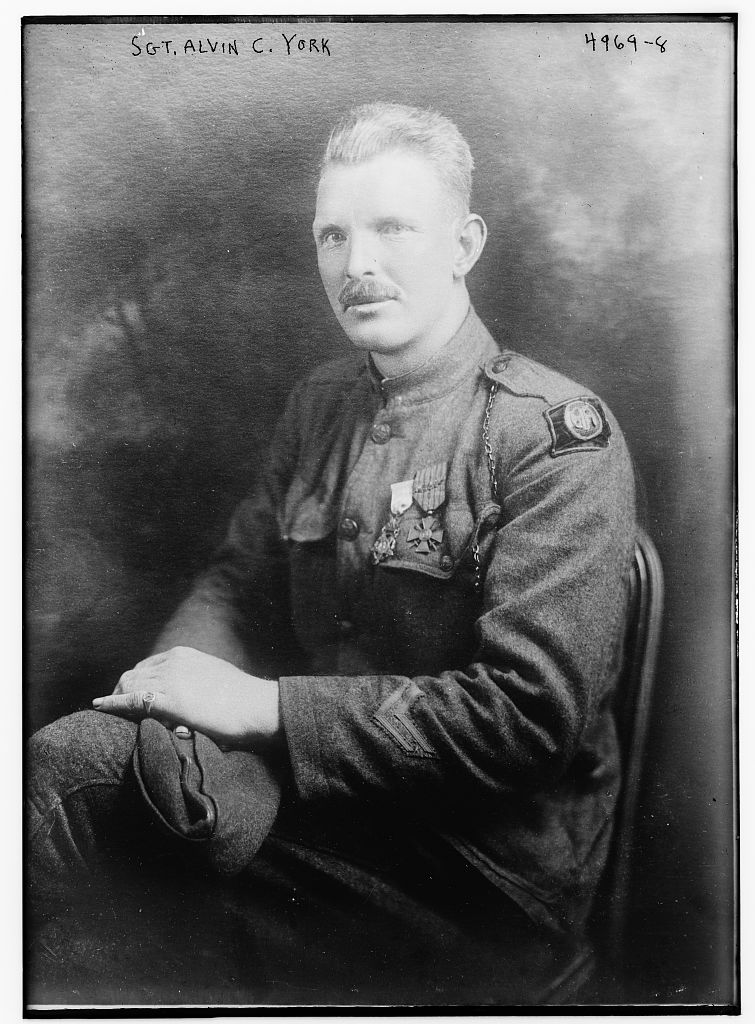

U.S. Army Corporal Alvin C. York gained hero status—becoming one of the most acclaimed American soldiers of World War I—after receiving a Medal of Honor for his actions at Châtel-Chéhéry, France, on Oct. 8, 1918. Initially conflicted by the pacifist beliefs of his youth and his sense of patriotic duty, the Tennessee farm boy deployed to the Meuse-Argonne region in May 1918. His rural upbringing proved a valuable asset when he employed his remarkable sharpshooting skills—gained from years of subsistence hunting—to subdue and ultimately capture a group of German soldiers responding to an American surprise attack. The following excerpt details York’s extraordinary leadership and the events that distinguish him as a war hero.

York and his battalion attempted to sleep on the drenched, muddy ground near the Aire River, only getting wetter and dirtier as heavy rain fell on them through the night of Oct. 7 and 8, 1918. At 3 a.m. Captain Edward Danforth and Lieutenant Kirby Stewart organized the men to begin their movement to Châtel-Chéhéry. According to the plan York’s battalion would pass through the remnant of the Americans holding Hill 223 and then wait for the moment to attack.

Although there was a fog in the Meuse Valley the morning of October 8, the day promised to be clear and sunny, giving the Germans excellent observation. As the Americans made the climb to the village, German lookouts on the edge of the Argonne Forest saw them. Within moments enemy artillery harassed the 328th Infantry Regiment’s movement to its jump-off line. The shells included poison gas, which further slowed the formation, as the men had to stop to don their masks and then move through the darkness with them on. One of the German artillery rounds exploded in the midst of the column, killing an entire squad.

Just as twilight was breaking, the men made it to Hill 223, much to the relief of the survivors who had held the hill against incredible odds since the previous day. One of the units York’s men relieved was Company B, which had lost 63 men. As the men of the 2nd Battalion waited for the order to attack, they all knew this would be a vicious fight.

As the Americans waited for the order to attack, the Germans were making final preparations to eject them from the Argonne entirely. The German battalion commander, Leutnant Paul Vollmer, just across the valley from the Americans, had a mix of good and bad reports that morning.

Things started to look up after the Bavarian 7th Mineur (Sapper) Company, under Leutnant Max Thoma, with a lead detachment of 17 men from the 210th Prussian Reserve Regiment, reported for duty around 5 a.m. Vollmer expertly placed the two units in the gaps on Hill 2. Thoma was satisfied with his position, and he colocated with the machine guns of Vollmer’s 2nd Company, which had excellent fields of fire up the valley. All of the gaps in Vollmer’s line were now sealed, and his men were ready to make this a bloody day for the Americans.

As the hour struck, things started to go terribly wrong for the Doughboys. The U.S. infantry units were ready to attack and waited for the supporting artillery to blast a way through the Germans. The barrage, however, never materialized. As the time ticked away toward the 6:10 a.m. assault, the officers had a quick meeting, with Major James Tillman deciding the men would go over with or without the barrage. He ordered the light mortar platoon and the machine-gun company supporting his unit to open fire with everything they had. Although making a lot of noise, these did nothing to the German defenders, who were safe in their positions.

At precisely 6:10 a.m. the officers of 2nd Battalion, 328th Infantry Regiment, blew their whistles and ordered the men to attack. As there were few trenches on Hill 223, the troops were largely crouching or sitting on the back slope of the hill jutting above Châtel-Chéhéry. The large American battalion attacked into the valley in two waves, with two companies in each wave moving parallel. One hundred yards separated the waves. York’s unit was in the second half of the lead attacking company on the left. Immediately they crashed into the remnants of the Germans’ Battalion Müller, hidden along the low western slope of Castle Hill. Battalion Müller held on until its 1st Company, 47th MG Sharpshooters, ran out of ammunition. Then the Germans retreated across the valley to the lines of the 125th Regiment.

With Battalion Müller out of the way, the Americans cleared Hill 223 and plunged into the valley. The Doughboys could not but be disheartened by the terrain now before them. As they came out of the woods behind Hill 223, the battalion entered a clear, steep valley about a half-mile wide. York described the terrible situation they faced:

The Germans met our charge across the valley with a regular sleet storm of bullets. I’m a-telling you that there valley was a death trap. It was a triangular-shaped valley with steep ridges covered with brush and swarming with machine guns on all sides. I guess our two waves got about halfway across and then jes couldn’t get no further nohow. The Germans done got us, and they done got us right smart. They jes stopped us in our tracks. Their machine guns were up there on the heights overlooking us and well hidden, and we couldn’t tell for certain where the terrible heavy fire was coming from. It ’most seemed as though it was coming from everywhere.

Things were far worse than any of the Americans realized. Major Tillman’s battalion was attacking alone, with no support on either flank. The Pennsylvanians, who were to advance on the left flank, had hit tough German resistance and were unable to move forward.

Due to a last-minute change in the plan Tillman’s battalion was also attacking in the wrong direction. Corps headquarters had altered the unit’s attack plan and objective early on the morning of October 8. Instead of attacking in a northwesterly direction to sever the German supply road in the Argonne, York’s unit was supposed to attack due west, so as to have the protection of the Pennsylvanians on their left. But the runner delivering the message to Tillman was killed just below Hill 223, and the order never arrived. The 82nd Division unit attacking on the right flank did receive the order, although only after it had attacked. Having the new plan, the supporting unit on the right of York’s battalion swung away to the north, leaving the battalion on its own, with both its right and left flanks “in the air.”

Leading the attack in front of York was his platoon leader, Lieutenant Stewart, holding his Colt pistol high in the air as he waved the men forward. As Stewart and his platoon reached the center of the open valley, a burst of machine-gun fire cut the lieutenant down, throwing him about like a rag doll. His legs were shattered. With every attempt to get up, he crumpled into a heap. Yet Stewart continued forward, dragging himself on the ground, waving his pistol in the air and yelling to encourage his men. Before the platoon could reach the lieutenant, another German bullet hit him in the head, killing him instantly. Command of the platoon went to Sergeant Harry Parsons.

As the Americans attacked to the northwest, the left flank was being racked by German machine guns. Parsons saw that the center hill the Germans called Humserberg was his biggest problem and that the machine guns on that specific hill had to be taken out. In this he was absolutely correct, as a large group of soldiers from the German 125th Württemberg Landwehr Regiment and a company from the 5th Prussian Guards were positioned there and had excellent lines of sight into the American flank. Parsons ordered Corporals Bernard Early, William Cutting, Murray Savage and York to lead their squads to take out the German machine guns on Humserberg.

Early was acting sergeant in charge of the four squads, with Cutting, York and Savage being his other noncommissioned officers. Two men from this element had already fallen in combat, leaving 17 soldiers to make the flank attack that would decide the outcome of the day’s battle. Early surveyed the ground as the squad leaders gathered their men in the midst of falling German artillery shells. Directly south Early saw a deep natural notch cut into the ridge and determined that was the best place to attempt the flanking maneuver.

As the group of 17 began their sprint for the southern hill, a barrage of artillery erupted near them. It was the belated American artillery support, at that moment rolling across the southern ridgeline and exploding amid the German 2nd Württemberg Machine Gun Company. The timing of the barrage caused the German gunners to seek cover just at the moment when the 17 Americans were in their sights. As a result all of the Americans made it up the hill unhurt.

Early led the group into the forest. For the men it was a relief to be out of the death trap of a valley. The platoon continued moving behind the German lines for some 500 yards. After a few minutes the Americans came across a shallow trench.

The trench was actually not part of the German defenses. Dug in the 17th century, it marked a border between private and communal land. Not constructed for military purposes, it was a straight trench, carved into the northern face of the southern ridgeline that overlooked the valley from which the Americans had come. The trench ended near the base of the hill, facing north, just above a supply road the Germans had carved into the Argonne. The Americans followed the supply road for a short distance west and came upon a small stream. Bending over the stream were two German sanitation soldiers, with Red Cross armbands, filling canteens.

The Germans momentarily froze in disbelief. When they saw the Americans surge toward them, the two dropped their water bottles, with loud, hollow metallic clangs, and fled for their lives. The Germans ran northeast, across a dense meadow, headed straight back to Vollmer’s headquarters to alert the commander to the presence of the Americans. The Germans ran as fast as they could, with the Doughboys hot on their trail.

Vollmer was busy directing his battalion against the Americans when his adjutant, Leutnant Karl Glass, approached. Vollmer was relieved to hear that two companies of the Prussian 210th Reserve Infantry Regiment had just arrived at the battalion command post and were awaiting his orders. The 210th was the force Vollmer needed to launch the much-anticipated counterattack to push the Americans out of the eastern portion of the Argonne. This would defeat the U.S. attack, save the day for the Germans and expose the flank of the main American attack in the Meuse Valley.

Suddenly, bursting from the foliage of the meadow, came the two soldiers Vollmer had sent to fill canteens, yelling, “Die Amerikaner kommen!” Just out of Vollmer’s vision, to his rear, the Prussians had reacted to what looked like a large group of Americans charging across the meadow. Believing it was an enemy penetration of some 100 troops, or perhaps American shock troops, the soldiers of the 210th were caught by surprise and surrendered. Before Vollmer realized what had happened, a “large and strong American man with a red mustache, broad features and a freckle face” captured him. It was Corporal Alvin C. York.

Early ordered his men to quickly search their 70 pris- oners, line them up and get ready to move. It was a chaotic situation. Around the 17 Americans were the sounds of war—from the valley to the east and the hills in front and behind them—as German gunners fired upon their brothers in arms in the death trap less than half a mile away. While the Americans were busy getting the prisoners in order, the 4th and 6th Companies of the 125th Württemberg Landwehr Regiment on Humserberg, just above the American patrol, realized there was trouble below.

A crew of German machine gunners under the command of Leutnant Paul Lipp was directly above Vollmer’s headquarters and had been firing to the east, into the diminishing ranks of the besieged American battalion. On seeing the capture of their countrymen below, the machine gun’s crew signaled to the captured Germans to lie down. As soon as that happened, the Württembergers opened fire. The hail of bullets killed six of the 17 Americans and wounded three more. The machine-gun fire also killed several Germans. With that the German POWs started waving their hands wildly in the air, yelling, “Don’t shoot, there are Germans here!”

The situation for York and the other Americans was not promising. Those who had survived the machine-gun fire were scattered across the meadow floor, lying on or near their German prisoners, who were also sprawled on the ground trying not to get shot. The German machine gun above them fired at anything that moved.

Being the only noncommissioned officer not dead or wounded, and with the burden of command now upon him, York determined to stop the killing. After a quick analysis of the situation, he seized the initiative. According to the account on his Medal of Honor citation, “He charged with great daring a machine-gun nest which was pouring deadly and incessant fire upon his platoon.” The seven other American survivors provided covering fire for York anytime he moved, with Private Percy Beardsley firing his Chauchat light machine gun in support. Most of the Americans later said the positions they ended up in after the German machine gun opened fire prevented them from doing much to aid York’s assault other than keeping watch over the prisoners.

To eliminate the machine gun causing so much death, York charged partway up Humserberg, crossed a German supply road about 160 yards above the meadow and took a prone shooting position just above the road. What York saw about 50 yards to the west were groups of German soldiers occupying two sunken roads that ran above and parallel to the supply road he had just crossed. York’s position was the tip of a V where the two sunken roads converged, with clear lines of sight up both roads. He opened fire, killing the machinegun crew and its supporting riflemen, a total of 19 Germans. He had fired nearly all of the rifle bullets from his front belt pouches in this engagement, some 46 rounds. He frequently yelled to the Germans to surrender so he would not kill more than he had to. His squad mates could hear him, but the Germans were oblivious to his presence.

As York contemplated what to do next, Leutnant Lipp was arriving from farther uphill with more riflemen. Taking advantage of the lull, York wheeled about to make his way back to the meadow to his men and the prisoners. As York came down the hill, he passed behind a trench occupied by Leutnant Fritz Endriss and part of his platoon. The German officer saw York and ordered his men to prepare for a bayonet attack. Endriss then charged out of the trench toward York, and 12 soldiers followed dutifully.

Seeing this, York slid on his side, dropped his rifle and pulled out his M1911 Colt pistol. Using a hunting skill he had learned when faced with a flock of turkeys, he picked off the advancing foes from back to front. The logic behind this was that if the lead Germans fell, the trailing soldiers would seek cover and be all the more difficult to kill. As Germans fell, several of the attackers broke off and headed back to the trench. By then half of the charging soldiers were dead. Right next to York, and unbeknown to him, Beardsley was also firing into the German throng. During the fracas a nearby German threw a hand grenade at York and Beardsley, but it exploded behind them in the meadow, wounding several of the German prisoners.

With the men of his platoon either dead or back in the trench, Endriss was now charging alone. When the German was only a few feet away, York fired. The impact of the .45-caliber bullet slamming into Endriss’ abdomen threw him backward, and he lay writhing and screaming in agony less than 10 feet from York. This occurred in clear view of Leutnant Vollmer, still lying on the meadow as a prisoner. There were now 25 dead Germans across the side of the hill.

In the midst of the fight Vollmer stood up, walked over to York and yelled above the din of battle in English, “English?!”

“No, not English.”

“What?” Vollmer asked.

“American,” York responded

“Good Lord!” the German officer exclaimed. “If you won’t shoot anymore, I will make them give up.”

Vollmer blew a whistle and gave an order, and the 125th Regiment’s troops dropped their weapons and made their way down the hill to join the other prisoners, under the charge of only eight Americans.

York used Vollmer to translate orders to the 100 or so prisoners. As they readied for the return to the American lines, York’s men expressed concern about whether they could handle so many prisoners. Hearing this, Vollmer realized there were not many Americans after all and asked how many men York had, to which York replied, “I have plenty.”

York ordered Vollmer to line up the Germans in a column of twos and to have them carry out the wounded. He placed the German officers at the head of the formation, with Vollmer at the lead. The corporal stood directly behind Vollmer, his .45 Colt pointed at the officer’s back, and decided which route to take back to the lines. Retracing their steps into the hills would be suicide, as there would be no way to control this large group of prisoners in that difficult terrain. York instead took them down the road that skirted the ridgeline to the south. This was the same road Early had led the men across when they spotted the first two Germans with the canteens. It was a good choice, as it led back to Hill 223 and Châtel-Chéhéry.

As they crossed the valley, the battalion adjutant of York’s unit, Lieutenant Joseph A. Woods, saw the formation from Hill 223 and believed it was a German counterattack. Woods gathered as many scouts and runners as he could to fight off this potential threat. But after a closer look he realized the Germans were unarmed and noticed York at the head of the formation, just behind Vollmer. At Hill 223 York saluted and said, “Company G reports with prisoners, sir.”

“How many prisoners have you corporal?” Woods asked.

“Honest, lieutenant, I don’t know,” York replied.

“Take them back to Châtel-Chéhéry,” Woods said, “and I will count them as they go by.”

He counted 132 Germans.

Originally published in the September 2014 issue of Military History. To subscribe, click here.