At a luncheon of the Distinguished Flying Cross Society in San Diego, president Chuck Sweeney let me make an announcement: “I’m researching for my book on aviation movies. Have any members been involved in working on Hollywood productions?”

A tall, lanky man with a full crop of nearly white hair and thick glasses raised his hand and said in a languid drawl, “I flew Japanese planes in Tora! Tora! Tora! Does that count?”

That was my introduction to retired U.S. Navy Commander Dean Laird. In his 30 years in Navy blue, Diz, as he prefers to be called, flew nearly every airplane in the naval aviation inventory, set speed and efficiency records, and was the only Navy ace to shoot down both German and Japanese planes.

With his mellow voice and easy wit, Diz Laird, now 97, acts more like a retired banker than an audacious fighter ace. Laird joined the Navy through the Naval Aviation Cadet program just after Pearl Harbor. “I already had my pilot’s license,” he explained. “I went through basic preflight at NAS [Naval Air Station] Oakland, and wound up at Pensacola. During operational training I flew the Brewster F2A Buffalo. I loved that plane. I’d been in Stearmans and SNJs, but this was a real fighter.”

Laird was assigned to VF-4, the “Red Rippers.” As part of the little-known Operation Leader, the fighter squadron embarked on the carrier USS Ranger to join the British Home Fleet off German-occupied Norway on October 4, 1943. At that time VF-4’s principal fighter was the outdated but tough Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat. “I happened to be on the CAP [combat air patrol] standby when a German bomber was spotted on radar,” he recalled. “But we couldn’t find it in the clouds and they told us to come on back to the ship. I kept looking back because I knew that there had to be something there. Then I spotted this German bomber about eight or 10 miles back coming out from behind a cloud. It was a Junkers 88. I hollered ‘Tallyho!’ and turned back. My leader joined me. The German saw us and immediately turned to the right and headed away. Boyd, my leader, went up on the right side of him and I was behind the German and shooting like hell, but I couldn’t tell whether I was getting any hits or not.”

Laird and his leader, Lieutenant Boyd Mayhew, made several attacks, attempting to bracket the Ju-88D in their crossfire.

“By this time the bomber was smoking,” continued Laird. “It didn’t look like he was really burning badly, but he was putting out an awful lot of black smoke. Boyd came running in on his second pass and broke off.” Then Laird moved in for the kill. “I was about two-thirds of the way through my run when the bomber exploded in a huge ball of fire and a bunch of little pieces flew off.”

As Laird and Mayhew turned to rejoin their flight and head back to Ranger, its radar plotted another German prowler. “Ten or 15 miles away from the fleet we ran into a solid cloud of rain,” said Laird. “We were paralleling the wall of cloud. I saw this shadow of an airplane flying very low and going in the opposite direction. I was down to about 25 feet because I needed to see the sea in all that rain. I lost sight of our planes.”

The enemy aircraft, a Heinkel He-115B twin-engine floatplane, came at Laird head-on. Reacting with the instinct of a born fighter pilot, he pulled up and turned into the German and triggered his guns. “I saw pieces fly off his port pontoon. I came up and around again. Now I was behind him and he was way out of range by then.” Unable to catch up, Laird was in a quandary. The optimum range for a stern attack was 300 yards, but the Heinkel was more than a thousand yards ahead.

Laird climbed until he was about 25 feet above the floatplane’s altitude and opened fire. He guessed his .50-caliber shells would drop about 25 feet over the thousand yards. Amazingly, his unorthodox tactic worked. Some of his shells seemed to strike as the Heinkel began to head to the stormy sea below, apparently intending to land.

“He touched down and that port pontoon collapsed,” Laird said. “The plane cartwheeled and came apart. Just then my buddies showed up and we turned back for the ship.”

Operation Leader lasted more than six months, but the only German planes encountered were those two downed by Laird and his flight.

“I wanted to be out in the Pacific where the Navy’s air war was really hammering the enemy,” commented Laird. He got his chance when Ranger’s Air Group 4 returned to NAS Quonset Point, R.I., in December 1943. VF-4 was based at Fort Devens in Ayer, Mass., where its pilots trained in the Grumman F6F Hellcat.

Laird and his squadron mates proceeded to the battle zone aboard USS Bunker Hill. On October 1, 1944, Lt. j.g. Laird was promoted to lieutenant.

On November 25, Laird got his first victory in the Pacific during a fighter sweep over Luzon. “I was a section leader for our squadron when we came over this airfield near Manila,” he said. “I called the squadron leader up and said: ‘There’s seven Tonys down there. Shall we go down and get them?’ But the squadron leader wanted them in the air so we waited for the Tonys to take off. In the meantime we were circling the field and getting shot at. I caught a few holes in my plane. At last these Tonys took off. The squadron leader and his wingman took the first two, and I and my wingman took the third.”

The Kawasaki Ki-61 “Tony” was a sleek Japanese army fighter with a liquid-cooled engine, armed with two 20mm cannons and twin 12.7mm machine guns. “I dived from about 8,000 feet, picking up quite a bit of speed,” Laird remembered. “I paralleled the Tony and tried a 90-degree shot. But I led too much and saw my tracers go in front of him. I dropped it back a hair and kept shooting, and he burst into flames. Then he turned into me and we passed each other by no more than 20 feet. He was totally in flames. My wingman was behind me and I thought he would take the next airplane taking off, but he didn’t. He stayed with me.”

Spotting another Tony taking off, Laird went after him, waiting until the enemy fighter reached 4,000 feet. Then he dived and rolled onto his back, performing a split-S maneuver intended to position him for the kill. But the Japanese pilot saw the blue Hellcat coming and evaded.

Recommended for you

“The next thing I know he’s climbing, trying to get up to where I was, which he couldn’t do because he hadn’t yet built up enough speed. He was pointed right at me and I aimed right at him. I couldn’t tell for sure where my tracers were going, but I was hitting his tail.”

The two fighters tried to gain an advantage, twisting and turning until Laird again moved in for the kill. But as with the first Tony, he led too much. “I said to myself, ‘You dummy, should have learned from the first one.’ This time I made sure I put my nose down and well in front of him. I saw my tracers hitting between the engine and the cockpit. Suddenly he flipped over into a spin, then dived into the ground. I had probably killed the pilot.”

The squadron claimed a total of seven victories, including Laird’s two. “I gave my wingman credit for one of mine,” he said. “We were a team and he deserved the kill for sticking with me like glue.

“About a month later we were transferred to USS Essex,” Laird continued. After several fruitless missions escorting anti-submarine torpedo planes around the fleet, he stormed into the scheduling officer’s office. “I said, ‘Charlie, I’ve had nothing but these garbage flights for the last two weeks. If I don’t start getting my share of the fighter sweeps I’m going to punch you right in the mouth.’”

The next morning, January 16, 1945, Laird awoke with a searing pain in his belly, but learned he had been given a fighter sweep. He didn’t dare beg off the mission and decided to endure the pain. The objective was the island of Hainan, separated from Guangdong by the Qiongzhou Strait, a hotly defended Japanese-held region in the South China Sea.

Laird and seven other F6F-5 pilots headed for the island. On the way they passed a single Curtiss SB2C-4 Helldiver and two Hellcats. When a Mitsubishi A6M5 Zero appeared, Laird went right at him and opened fire. “I thought he would turn to the left and I turned to meet him, but he turned to the right. I hit him pretty hard, but not hard enough to knock him down. I fired some more long-range shots at him. One of his landing gear struts fell down and I knew I had hurt him. Then I saw the Helldiver being pummeled. ‘Get up there and help those search guys and I’ll take care of this one,’ I said to my division as I kept after this guy. But that Zeke was faster than my Hellcat and even with one landing gear hanging down I couldn’t gain on him.

“Then another plane at higher altitude came close, and I saw it was a [Mitsubishi A6M3] Hamp, which had squared-off wingtips. He was coming to join the fight but taking the long way around. I climbed and gave it full throttle and met him head-on. When I fired he suddenly dumped over without firing a shot. I must have hit the pilot, and he went right into the water.” Laird then climbed to rejoin the rest of the fighters and saw another Zero chasing his wingman. Even though he was far below and almost out of range, Laird took careful aim and began firing. To his surprise the Mitsubishi started smoking and broke off the chase.

Together, Laird and his wingman located the rest of the force. Returning to Essex, Laird climbed out of his Hellcat and made his combat report to his squadron commander. “I went to my room and laid down,” he said. “The pain was just terrible. I had been flying for six hours. I finally called sick bay. A doctor answered and I said, ‘Doc, I’ve got this terrible bellyache. Can you send up a laxative? Maybe that will help.’”

Essex’s medical officer said he was coming to see Laird, and after examining the pilot called for two orderlies and a stretcher. Protesting, Laird was taken to surgery, where his badly inflamed and distended appendix was removed. “The doctor said, ‘You’re the luckiest guy I know. If that appendix had burst, you’d be dead.’ That sobered me right up.”

February 16 saw Laird over the Japanese Home Islands, and this time the targets were twin-engine Mitsubishi Ki-21-II “Sally” bombers. He was with a group of 20 Hellcats and an air group from another carrier flying Vought F4U-1D Corsairs.

“Somehow in the thick overcast I lost most of my group and there were only four of us left,” he said. “The other group commander told us four to stay up and provide cover for his two photoreconnaissance Corsairs while he and the others went down and tore up the field. That wasn’t what I had in mind, but I agreed. Then I looked down and saw these two bombers take off. I thought, ‘Man, I’d like to go down and get them.’ But even with the Corsairs diving and strafing, none of them saw these bombers.”

Unwilling to wait any longer, Laird told his second section to remain with the photo planes while he and his wingman attacked the bombers. “I went after the wingman bomber and fired a burst, making sure I led him. He just disappeared in a big ball of fire and a bunch of parts falling away. I was going so fast I knew I’d overshoot the leader, so I throttled back to idle and slowed enough that I rolled over and came back down by him. I hit him on two passes, then came alongside. His cockpit was full of flame. The emergency hatch came open and these three crewmen jumped out. They had no parachutes. I watched them fall from 2,500 feet. Didn’t take them long to hit the ground.”

In April 1945, Laird returned to the States as an ace credited with 5¾ victories. He was assigned to Experimental Fighter Squadron 200 (XVF-200) in Brunswick, Maine, playing the role of kamikazes “attacking” ships in the harbor so the Navy could develop better defensive tactics against the suicide planes. “That was exciting,” he admitted. “We had 16 F8F Bearcats, 10 F6F Hellcats and 10 F4U Corsairs. I was in command of the Corsairs. I stayed in the squadron until after the war ended.”

Laird continued to stand out among his peers. “In 1947 we had an inspection, and the captain who issued the final report said, ‘I have to say the gunnery, bombing and rocket exercises I completed with Lieutenant Laird are the best I’ve ever seen in my life.’ Afterward he said to me, ‘Diz, do you want to get into jets?’”

Laird smiled at the memory. “I said, ‘Sir, I’d give my right family jewel.’” He eventually qualified in the McDonnell FH-1 Phantom and F2H Banshee in April 1948.

“In 1949 somebody had the idea of having a jet race, and four of us from VF-171 went to Cleveland,” Laird related. He and three other pilots flew Banshees from the deck of USS Midway in New York during a special carrier demonstration flight. “I won the race with an average speed of 549 mph, the fastest speed recorded by any race at the time.”

this article first appeared in AVIATION HISTORY magazine

Facebook @AviationHistory | Twitter @AviationHistMag

In 1969 Laird, who was stationed at NAS Miramar, found himself playing the part of his former adversaries—a “Japanese” pilot, flying replica fighters and bombers in 20th Century Fox’s epic production Tora! Tora! Tora! “I got a call from a friend in Washington who was looking for pilots with experience in flying tail-draggers,” he said. “He told me what it was all about and I was sent up to MCAS El Toro near Los Angeles, where I found these AT-6 Texans and BT-13 Valiants that had been modified into Japanese Vals, Kates and Zeros. I was the first to fly them and get a feel for their handling qualities. The ‘Kates’ were basically extended Texans with several feet added to the fuselage ahead of and aft of the wings. The ‘Val’ was the BT-13 with wheel spats and a modified tail. I think there were 33 in all, 11 each of fighters, torpedo planes and dive bombers. The Kates were tricky to fly, being very nose-heavy and slow, but we flew them down to NAS Coronado.”

On the Coronado Golf Course that day were retired Admirals Elliott Buckmaster and Max Leslie. Buckmaster had been Yorktown’s captain during the Battle of Midway, and Leslie had commanded the carrier’s Bombing Squadron 3. Laird recalled with a smile: “I was told later that when we flew over the course Buckmaster turned to Leslie and said, ‘Jesus, Max, I thought we shot all those sons of bitches down!’”

The planes were moved down to the dock and loaded aboard the second carrier Yorktown (the first had been sunk at Midway). Off the coast of California, Director Richard Fleischer re-created the historic predawn launch of the enemy strike force. Yorktown’s modern flight deck had been overlaid with a false bow and wooden planking to stand in as the carrier Akagi. Laird’s Val was first to launch as he and George Watkins led the planes into the dawn skies. The aircraft were then ferried to Hawaii.

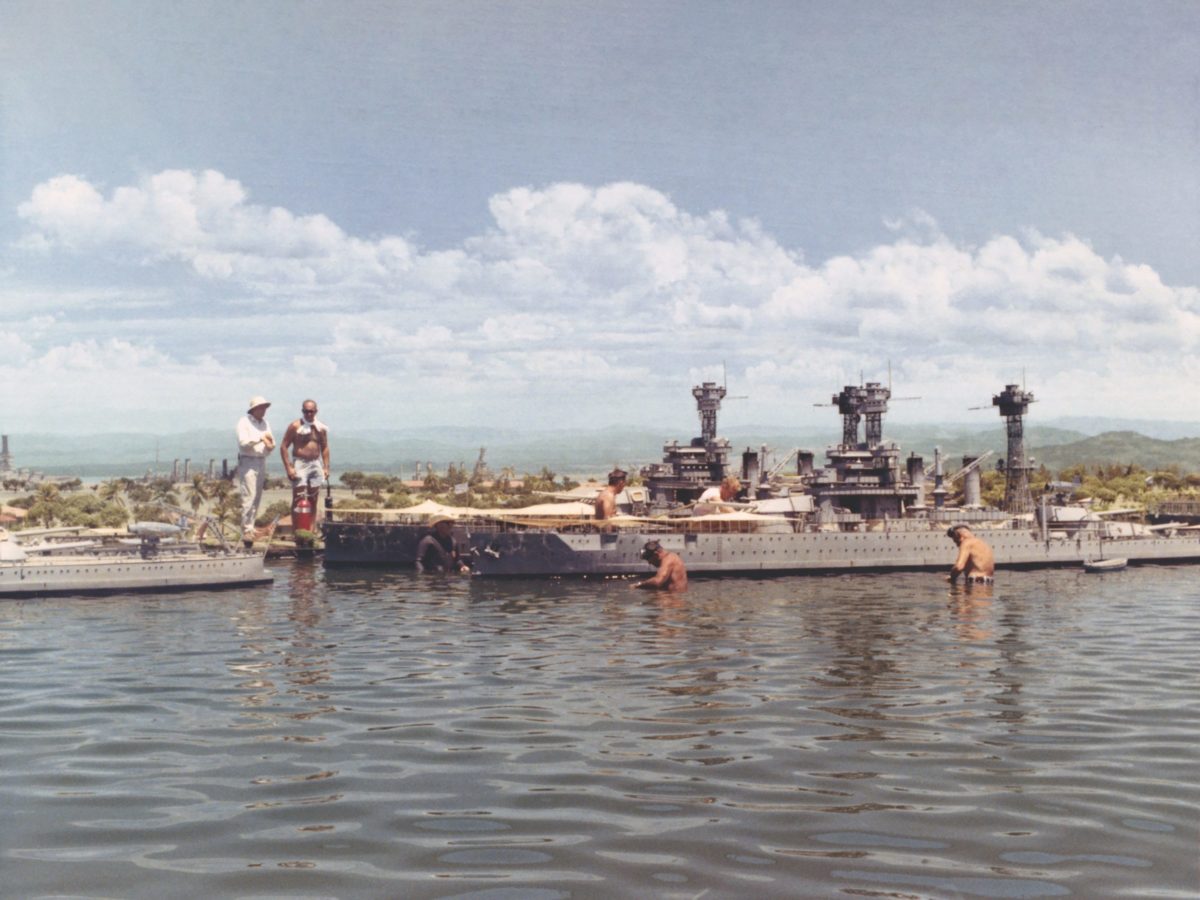

Retired Air Force Lt. Col. Colonel Arthur Wildern was the chief pilot for the Pearl Harbor attack sequences. He led a team of 47 off-duty and retired Navy, Marine, Army, Air Force and Air National Guard pilots who flew the Japanese and American aircraft. They had to have extensive close-formation skills as they would be flying in tight quarters and at extreme low level over active Navy and Air Force facilities. Laird and his fellow pilots logged more than 4,000 hours in the air while they “bombed” Pearl Harbor. “It was run just as if we were planning a real strike,” he said. “A forward air controller worked with the cameramen to tell us when to come in on a run or do a retake. For most of the shots there were only three planes, just Art and myself and a young Marine who had just come back from Vietnam. We wore Japanese flight jackets and brown leather helmets with fur lining.

“I was in one of the Kates during the first attack on Battleship Row. We came in low, banked and headed in. Of course there weren’t any ships. That came later. But it was incredible.”

Laird continued flying jets and racking up more than 8,000 total hours in the air, including 4,700 in jets, until he retired as a commander in 1971. “I’ve been very lucky,” he said.

On July 9, 2016, the 95-year-old pilot took the controls in the back seat of a Beechcraft T-34C Turbomentor, and with Lt. Cmdr. Nicole Johnson up front, took off from Coronado and did some sightseeing off the coast of San Diego, followed by both fliers performing aileron rolls over a training area. It was the 100th airplane type to grace his flight log.

Mark Carlson writes from San Marcos, Calif. His most recent book is The Marines’ Lost Squadron: The Odyssey of VMF-422. Further reading: Fire in the Sky: The Air War in the South Pacific, by Eric M. Bergerud; and Pacific Air, by David Sears.

This feature originally appeared in the May 2018 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe here!