Separated from Southern-sympathizing Manhattan, Brooklyn had one of the largest and most politically aware Black communities in the U.S.

On September 26, 1850, six days after President Millard Fillmore signed the federal Fugitive Slave Law requiring Americans to aid in the capture and return of runaway slaves, two deputy U.S. marshals arrested James Hamlet in New York City as he was working at his job as a porter. Hamlet, a runaway slave, had fled bondage in Baltimore, Maryland. He had arrived in New York by train in 1848 and, with his wife and three children, had settled near Brooklyn in a township then called “Williamsburgh.” Distance conferred only the illusion of freedom. Hamlet’s owner, Mary Brown, dispatched slave catchers—her son Gustavus Brown, son-in-law Thomas Clare, and a hired agent. In New York, the three presented documents to a federal official who ordered Hamlet arrested and, on the spot, held a hearing at which Hamlet was barred from testifying. The presiding officer agreed that Brown owned the Black man, ordered Hamlet shackled, and had the prisoner hustled aboard a steamship to Baltimore, where Brown put her returned human chattel up for sale.

The Hamlet episode marked the Fugitive Slave Law’s debut. The case emphasized the difficulty of implementing that much-disputed measure, enacted to compel the return to slave states of runaways in free states. Previously, slaves who reached a free state could claim freedom. Hamlet’s pursuer, Thomas Clare, told the New York press the price of his prisoner’s freedom was $800. On September 31, more than 2,000 members of Black civic organizations and a “slight and visible sprinkling of white abolitionists” packed the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church on Church Street in Manhattan; a pass of the collection plate met Brown’s price. Back in New York, Hamlet appeared October 5 at a “great mass meeting of colored citizens” at City Hall Park in Manhattan. He told the crowd that when he was to go on the block in Baltimore would-be purchasers heard warnings to avoid buying him because “he had tasted liberty, and therefore could never be held again in chains.”

Hamlet’s experiences and those endured by other runaways showed that amid Northerners’ gathering resentment toward Southern domination on the slavery question, the Fugitive Slave Law would be impossible to enforce. In particular, Hamlet’s odyssey illustrated the existence of a thriving community of activist free Blacks in Brooklyn who, along with white abolitionists, were mobilizing to resist slavery.

By 1850, Brooklyn’s 200,000-plus population included one of the country’s largest free African-American communities. Blacks had been present there since the 1600s, initially as slaves brought to Bruijkleen, an agricultural district of Dutch colony New Netherland. Slavery had been part of life in New England since the earliest colonial times, first with Indians forced into labor. Considered too dangerous to roam the colony, Native American prisoners of war were often traded to West Indies sugar planters in exchange for enslaved Africans. Farmers in Bruijkleen bought slaves because, thanks to prosperity at home, no Hollanders were desperate enough to indenture themselves, contracting to work for a stipulated number of years in exchange for passage, provisions, and shelter. The Dutch let slaves own property, serve in the militia, and testify in court, but during winter and fallow times slaves had to fend for themselves, growing or hunting their sustenance. Dutch slaveowners could grant long-serving or deserving slaves “half-freedom” with colonial officials’ approval—and an annual payment to the colony by the half-free individual. When England conquered New Netherland in 1664, royal proprietor James, duke of York, wanted to recast his acquisition as a European settlement instead of a trading outpost. To attract Englishmen who were used to having servants do the heavy farm work, the duke encouraged the purchase of African slaves. By 1746, more than 9,000 adult slaves were living in New York, giving the colony the largest slave population north of Maryland. The slave ranks in Kings County townships Flatbush, Flatlands, Gravesend, New Utrecht, Brookland, and Bushwick rose from 14 percent in 1698 to 21 percent in 1738. For large landowners, the ranks of slaves owned served as status symbols. A typical small farmer owned one or two men for field work, and perhaps a female domestic. Most local bondsmen lived in small households and had to support themselves while living crammed into cubbyholes, attics, and outbuildings.

Owners could profit by renting slaves with desired skills. This made it worthwhile to train bondsmen at coopering, blacksmithing, and carpentry, and, as New York became more urban, baking, tailoring, tanning, shoemaking, and goldsmithing. When not toiling for their masters, slaves could seek paid work; many did hire out, accumulate savings, and buy their freedom, a pattern central to the growth of free Black communities in New York City and its neighbor across the East River whose name had undergone anglicization to “Brooklyn.”

Others joined the community through flight or a casual form of freeing. Britain had outlawed the old Dutch “half-freedom” but allowed owners to dispose of elderly or sick slaves by turning them loose. Runaways from rural districts on Long Island and further north in the colony often disappeared into New York’s crowded streets, as did slaves fleeing bondage elsewhere. Some stowed away aboard ships leaving Southern ports. Others walked from Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maryland, and Delaware. During the Revolutionary War, British troops occupying Long Island, Manhattan, Staten Island, and New York counties east of the Hudson River offered rebel-owned slaves freedom if runaways reached Crown territory. This policy quadrupled the local fugitive slave population. With Britain’s defeat, American loyalists expatriated to Crown territories like Canada and the Bahamas, sometimes taking along their slaves. Other Blacks stayed behind, now free.

Northern colonists held thousands of slaves until the Revolution, when pressure from a lingering Puritan ethos, the rhetoric of independence, and a dearth of cash crops requiring gang labor prompted many owners to manumit bondsmen. In the 1780s, most northern states’ legislatures mandated gradual emancipation, a trend to which New Jersey and New York, more dependent on slavery, were late. New York’s elite formed the New York Manumission Society in 1785. Pressed by that body, the state dropped a requirement that owners assure good behavior by manumitted persons and made it even easier for owners to free slaves who were of diminished utility. Not until 1799 did the New York legislature pass a gradual emancipation bill promising enslaved children born after its enactment freedom at age 28 for men and 25 for women.

In Brooklyn, enslaved and free Blacks found work in shipyards, at rope walks—expanses on which workers made rope by intertwining strands of hemp as they strode along—and with waterfront sugar refineries, adding racial diversity to those businesses. Black sailors crewed coastal vessels. Black women worked as domestics, midwives, laundresses, and cooks.

Blacks lived in downtown Brooklyn, in the vicinity of the Fulton Ferry landing, and in a waterfront neighborhood, later called Vinegar Hill, that stretched from Bridge Street to the navy yard. Residents established mutual aid organizations like the African Woolman Benevolent Society, founded in 1810, to provide burial and property insurance, business loans, and charity. Black congregations erected churches: Concord Baptist, Siloam Presbyterian, Bridge Street African Wesleyan Methodist Episcopal, and others. All became important social centers whose pastors preached saving money to help family and friends buy freedom. New York abolished slavery on July 4, 1827.

In the 1820s, individual Quakers in southern Pennsylvania and in an enclave in North Carolina began assisting slaves fleeing bondage, an effort that evolved into the Underground Railroad. Never the structured web of “stationmasters” and safe houses portrayed in late 19th century abolitionist historiography, the Railroad did shelter and direct northbound runaways, who generally had white help until they had traveled well into free territory. “Conductors” were mostly fellow slaves and free Blacks willing to risk hiding fugitives and forge passes and manumission papers. New York City was a scene of pause for runaways who were heading to Syracuse, Albany, and other upstate cities known as hubs of support. Immigrants hostile to Blacks crowded Lower Manhattan; to the familiar phenomena of Catholic-Protestant rioting and anti-immigrant violence, New Yorkers added strings of white-on-Black attacks. Brooklyn, insulated by the unbridged East River, offered Blacks a degree of refuge.

Jim Pembroke, enslaved on a wheat farm near Hagerstown, Maryland, was a skilled mason and blacksmith. His owner thought him insolent and caned him for his attitude. In 1827, Pembroke ran. Detained by white men when he could not produce the papers they demanded, he slipped away in the dark. Near Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, a helpful toll collector sent Pembroke to William Wright, a Quaker farmer and Underground Railroad figure. Pembroke stayed six months with the Wrights. Learning to write, reading the Bible, and being introduced to arithmetic and astronomy, he took the name James W.C. Pennington, probably to honor a prominent Quaker family, and took off to Brooklyn.

A lawyer hired Pennington as a coachman; he used his wages to engage tutors. Starting in 1830, Pennington represented Black Brooklyn at yearly conventions of prominent African-Americans. In 1834-35, Yale Divinity School grudgingly let Pennington audit classes. He pastored a number of New York congregations, including Manhattan’s Shiloh Presbyterian Church, and became a leading Black writer and intellectual. During the Civil War, he recruited volunteers for the U.S. Colored Troops.

Other black activists in and around Brooklyn led the antislavery movement and helped fugitives escape. Charles Ray, born free in Falmouth, Massachusetts, in 1807, studied at Wesleyan College in Connecticut until fellow students’ racist protests drove him away. He farmed and learned boot making, and in 1832 opened a shoe store in New York. Ray, ordained a Methodist minister, joined the American Anti-Slavery Society at its formation in 1833. He pastored two predominantly white Congregational churches and for a time edited The Colored American, an abolitionist weekly. In 1835 Ray helped found the New York Vigilance Committee, devoted to foiling slave catchers. Chapters formed in Williamsburgh and Brooklyn. Principals included black ministers Samuel Cornish and Theodore S. Wright, both of Manhattan’s Shiloh Presbyterian, and the fiery David Ruggles, the committee’s leader 1835-40. The Vigilance Committee raised money, printed and distributed pamphlets and broadsides, hired lawyers to argue cases on behalf of individuals snatched by slave hunters, and sheltered hundreds of northbound fugitives. Ruggles prowled the wharves offering aid to runaways. State law restricted to nine months the term that Southerners bringing slaves into New York could maintain ownership of that human chattel. Ruggles made note of such visitors, confronting slavers who had overstayed their time. He often struggled with New York City Recorder Richard Riker, mainspring of the “Kidnapping Club,” a cabal of judges and constables who cooked up slapdash hearings and whisked Blacks, some legally free, into bondage. Ruggles broke with the committee over tactics and complaints that he diverted committee funds for his own use.

Black Brooklyn grew. In 1832, chimney sweep William Thomas bought and subdivided 30 acres on Hunterfly Road in Flatbush, well away from whites. He sold building lots to fellow African-Americans. Nearby, in 1835, using profits from his boot-blacking manufacturing company, “colored” Henry Thompson bought 32 parcels of land from the estate of slaveholder John Lefferts, for whom Lefferts Avenue is named. An 1837 recession generally crushed American land prices.

In 1838, Thompson sold Virginian James Weeks acreage on which the buyer, a free Black stevedore, started what he called Weeksville, a development soon boasting more than 800 residents, a school, two churches, an orphanage, a cemetery, and abolitionist paper The Freedom’s Torchlight.

Weeksville and kindred Brooklyn neighborhoods attracted fugitive slaves who took up residence and helped others move along to New England and Canada.

The 1840 passage of a state law requiring a jury trial when slave catchers sought to arrest runaways discouraged bounty hunters from roaming New York in search of truant bondsmen. However, in 1850 the Fugitive Slave Act overrode such state “personal liberty” laws. The federal law barred aid to runaways and required Americans to help return fleeing slaves to owners. Violators risked a $1,000 fine and six months behind bars. The law provided bonuses and promotions for officials remanding fugitives, heightening tension. “Let parents and guardians, and children take warning,” wrote The Emancipator, an abolitionist paper. “Our city is infested with a gang of kidnappers—Let every man look to his safety.”

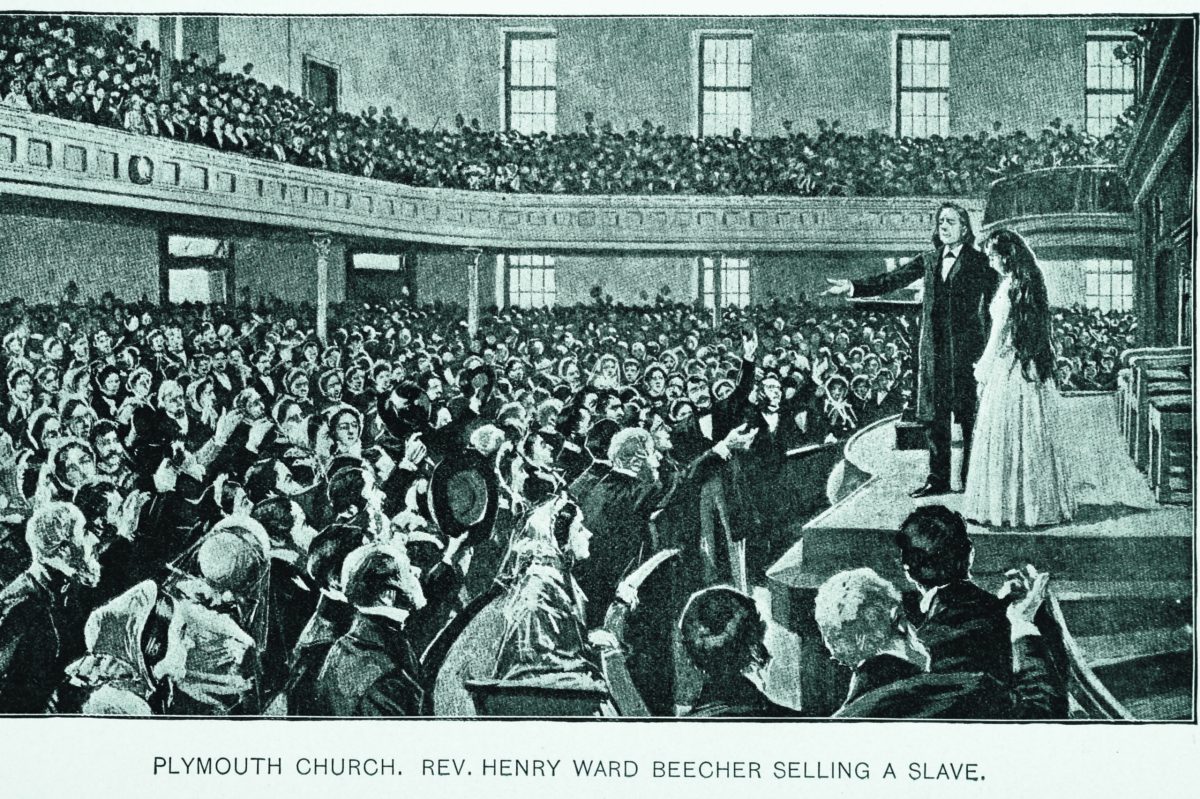

Strictures against helping runaways fanned abolitionist fervor in white Brooklyn congregations like Plymouth Congregational Church on Orange Street in Brooklyn Heights. Plymouth Congregational’s pastor, Henry Ward Beecher, was a younger brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of antislavery pot-boiler Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Beecher railed at slavery from the pulpit and used donations to buy Sharps rifles he sent to free-soil settlers battling pro-slavery forces in the Kansas Territory. He was a masterful publicist. “Fugitives make their appearance continually, pleading with pathos deeper than words, for shelter and aid in their flight,” Beecher said. “I will shelter them, conceal them, or speed their flight; and while under my shelter, or under my convoy, they shall be to me like my own flesh and blood; and whatever defense I would put forth for my own children, that shall these poor, despised creatures have in my house or upon the road.” Runaways hid in the cellar beneath the Plymouth sanctuary. Upstairs, Beecher held fundraisers and “auctions” at which bidders donated money to buy freedom for runaways who were under the church’s care.

Plymouth Congregational was one of many Brooklyn-based Underground Railroad “stations.” Others were in Weeksville, Carrville, and Williamsburgh. In downtown Brooklyn, occupants of a house at 233 Duffield Street built into their residence a secret passage for use by runaways. At 227 Duffield, abolitionists Thomas and Harriet Truesdale built a tunnel that may have led to nearby Bridge Street Church. Rescued fugitive James Hamlet kept a safe room in his home on South 3rd Street. At his home on Smith Street, James Pennington harbored runaways. So did wealthy white merchant Lewis Tappan, in his four-story brownstone at 86 Pierrepont Street in Brooklyn Heights (See sidebar, below. One escape in which Tappan participated grew out of a highly publicized international effort to free an extended family enslaved in Maryland—a story that was rendered particularly compelling by the family’s size and its female children’s vulnerability.

Ann Maria Weems was born into slavery in Rockville, Maryland, in 1840. Her father, John Weems, bought his freedom from, then worked as a laborer for, Rockville planter Adam Robb. After Robb’s death, his daughter sold John Weems’s enslaved wife, Arabella, and seven of their offspring to innkeeper Charles Price. Daughter Stella, 17, escaped to Geneva, New York. To end-run the Fugitive Slave Law, prominent minister Henry Highland Garnet, who had fled slavery himself, adopted Stella and took her with his family to England. Speaking to antislavery groups there, Garnet often told the Weems family story. John Weems tried hard to free his family, traveling to New York to importune the well-known abolitionist Charles Ray for assistance. Ray enlisted Garnet to raise money in England to help the family. Garnet worked the press and, with Quakers Henry and Anna Richardson of Newcastle, raised $5,000 for a “Weems Ransom Fund.” Ray and Lewis Tappan were to get the money to John Weems. Weems returned to Maryland. Charles Price, the planter who now owned Weems’s wife and children, had moved Arabella and their five sons to a slave pen in Washington, DC, where he sold them for $3,300 to an Alabama planter. Price kept daughters Ann Maria and Catharine Weems.

The abolitionists had sent John Weems enough money to buy one daughter. Catharine was older and at greater risk of sexual predation; her father bought her freedom. Abolitionists in the South stood ready to help Weems find and free his other loved ones; the challenge was getting money to the agents. In Alabama, a representative bought Arabella and the two youngest boys for $1,650. Three sons remained enslaved there. Quaker attorney Jacob Bigelow of Washington, DC, offered Price $700 for 13-year-old Ann Maria. Price demanded $1,000. Bigelow returned to Washington without the girl. For a year, Ray and Tappan argued, with Tappan accusing Ray of misusing money from the ransom fund. On September 23, 1855, Ann Maria, now 14, stole away to Bigelow’s home in Washington. Two months later, an escape plan took form demonstrating Underground Railroad operatives’ ingenuity. On November 25, sympathetic physician Ellwood Harvey parked his carriage on Pennsylvania Avenue NW in front of the White House. Ann Maria Weems appeared, hair shorn and tucked beneath a man’s cap. Wearing a livery driver’s uniform down to the bow tie, the girl took the reins and steered the carriage north to Philadelphia.

From there, Underground Railroad conductor William Still got Ann Maria to Brooklyn. Through Charles Ray, Lewis Tappan and wife Sarah used $63 from the ransom fund to buy her clothes and a carpetbag. Ann Maria and Black minister Amos Freeman rode openly by train to Buffalo. On December 1, the pair crossed the Niagara River into Ontario, Canada. Ann Maria reunited with relatives in Dresden, Ontario. She stayed in Canada the rest of her life.

In 1856, Tappan and cohort bought Ann Maria’s brothers Joseph and Adam for $1,700. The same sum went to free the oldest Weems son, Augustus, in 1857. Usually a 22-year-old bondsman fetched more, but Augustus had tuberculosis. He died within a year.

Abraham Lincoln and fellow members of the new Republican Party hesitated to join calls to repeal the Fugitive Slave Act, but it became clear through the 1850s that no court in the North was going to prosecute any Northerner for aiding fugitive slaves. In the Midwest and New England, the Underground Railroad was operating in the open. In New York City, where businessmen and politicians feared alienating Southern business partners, especially those in the cotton, tobacco, and rice industries, which were dependent on enslaved workers, the Railroad ran in deep secrecy. When slaveholding states seceded and civil war began in 1861, Brooklyn counted fewer Confederate sympathizers than New York City; many Brooklynites enlisted in the Union army. Several early volunteer Union regiments grew out of New York State militias, including the 14th Brooklyn Regiment, which Henry Beecher’s flock at Plymouth Congregational adopted as its own. Brooklyn contributed much to the Union effort, including the construction of the ironclad USS Monitor at Continental Iron Works in Greenpoint. Women of Beecher’s congregation made bandages, knitted socks, and sewed uniforms for “the Plymouth boys.”

History mainly remembers New York City’s 1863 Draft Riots. That disturbance eclipsed an incident in August 1862 at Watson’s Tobacco Company in Cobble Hill, Brooklyn. The factory’s Black cigar rollers, many of them former slaves, were making $14 a week. White laborers, mostly Irish, made $10 a week. A Saturday night stare-down between white and Black Watson’s workers escalated into a fight. A rumor circulated that Black men had “insulted” white women. On Monday morning, August 4, five Black men and 20 women and girls were working at the cigar-rolling factory when 400 whites stormed the building. The workers barricaded themselves in on the second floor. One Watson’s Tobacco Company employee, Charles Baker, a Black man, was beaten severely.

Police rescued Baker, who was arrested for striking an officer. Rioters, some yelling “Kill the Black sons of bitches!” and wielding pitchforks, tried but failed to torch the factory. Police arrested eight whites. Charges against Baker were dropped. In court, the defendants argued that they were standing up for their rights.

The Draft Riots started in Manhattan Monday, July 13, 1863, two weeks after the Battle of Gettysburg. By the end of the first day rioters, infuriated at being conscripted to fight for emancipation, turned their fury on any Black person they could catch. Whites lynched 11 Blacks. At least 119 people died in the riots and in a fire that destroyed the Colored Orphan Asylum. Twenty percent of Manhattan’s Black population fled the island by ferry for the relative safety of Brooklyn. Many never returned.

_____

The Tappan Brothers: Silk and Defiance

Manhattan merchant Arthur Tappan disliked conversation. The shy, bad-tempered, headache-prone silk importer hunched at a table writing correspondence while younger brother and partner Lewis, slightly less waspish, supervised their 20 clerks. Arthur Tappan & Co., in the early 1830s one of America’s richest business enterprises, sold fabrics and fashion accessories from Europe. Deeply religious, the brothers bankrolled the abolitionist movement of the 1830s and ’40s against their bankers’ wishes. “You demand that I shall cease my antislavery labors…or make some apology or recantation,” Arthur Tappan declared. “I will be hung first!”

The Tappans, born in 1786 and 1788 in Northampton, Massachusetts, grew up in the Calvinist Congregational Church. They gave up Calvinism to join the 19th-century evangelical movement, which preached the importance of good works. Arthur started his New York business in 1815. As he prospered, he donated money to train ministers and missionaries, promote temperance, distribute Bibles, rescue prostitutes, and educate Black youths. He initially supported an American Colonization Society campaign to expatriate free Blacks to Africa.

However, upon learning that Liberia’s American sponsors intended to sell the colony’s inhabitants rum and firearms, Arthur quit the society. Lewis, a talented manager, joined Arthur’s firm in 1827 as a partner. In 1830, the brothers met Boston abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, an encounter that launched their lifelong antislavery crusade.

In 1833, the Tappans and Garrison formed the American Anti-Slavery Society, outraging businessmen and newspaper editors in New York City who supported the South, along with poor white workers fearing competition from freed Blacks. Mobs disrupted the society’s first two Manhattan meetings. On July 9, 1834, toughs rifled Lewis Tappan’s house on Lower Manhattan’s Rose Street and burned his belongings in the street.

At the Tappan & Company store the next night, rioters began battering the door. Inside, Arthur Tappan passed out guns.

“Steady, boys,” he said calmly. “Fire low. Shoot them in the legs, then they can’t run!” Soldiers dispersed the mob.

In 1835, Arthur Tappan poured money into Oberlin College in Ohio in return for a pledge to admit “promising” African-Americans, treat them equally with whites, and become the first integrated college in the United States. That year the brothers funded a campaign to mail abolitionist pamphlets to churches around the South. Learning that a load of those materials had arrived at the Charleston, South Carolina, post office, a crowd broke in and seized the mailbags. Three thousand people cheered as rioters burned the pamphlets and hanged Arthur Tappan in effigy. Southern newspapers offered rewards to anyone who kidnapped Arthur to be tried for inciting slaves to rebel. Dismissing the threats, Arthur commuted daily from his Brooklyn Heights home to his Manhattan store. Told he had a $50,000 price on his head, Tappan said, “If that sum is placed in the New York Bank, I may possibly think of giving myself up.”

In truth, the Tappan brothers considered Blacks inferior to whites. Arthur Tappan once sat in a church pew with a mulatto minister; mortified by the ensuing public outcry, he vowed never to do so again. Nor did he ever hire a Black man for any job but porter. Lewis disparaged Black abolitionists and Underground Railroad leaders, saying he had never met a Black man who could be trusted with money.

On December 16, 1835, fire raced through downtown Manhattan’s commercial district, south of Wall Street. The blaze destroyed 650 buildings, including Tappan & Company on Hanover Square. Black neighbors had enough time to transfer some of the Tappans’ inventory to a safe warehouse before the building and contents, including $500,000 in notes from creditors, burned. Tappan & Company went bankrupt in 1837.

To cover debts, Arthur Tappan cut back his charitable giving. The company limped along for a few more years before folding.

In 1840, the American Anti-Slavery Society broke apart. The conservative Tappans believed the Constitution protected slavery but thought they could end the practice by appealing to Southerners on moral grounds. William Lloyd Garrison’s wing of the society believed the Constitution to be illegal and that only political upheaval would eradicate slavery. Garrisonians demanded the North secede from the Union and re-form in a federation mandating equal rights for all. The last straw was when the radicals, flouting convention, elected a woman to the society’s business committee. The Tappan brothers and 300 adherents formed the conservative American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society.

In the early 1840s, his health fragile and his fortune gone, Arthur withdrew from public antislavery activity. Lewis stepped up: In 1840, 52 Africans kidnapped in what is now Sierra Leone took over the slave ship Amistad and ended up in New Haven, Connecticut, charged with piracy and murder. Lewis Tappan organized the escapees’ defense. It took two years and two trials but the “Amistads” were freed.

Lewis Tappan resigned from Tappan & Co. in 1841 to organize a credit-reporting firm, the Mercantile Agency, which for a fee researched small-town merchants seeking capital. Lewis, determined to enforce morality in the marketplace, recruited a far-flung network of analysts including a young Abraham Lincoln. Many “correspondents” were fellow abolitionists. “The M[ercantile] Agency is now quite popular here,” Lewis wrote in 1843. “It checks knavery, & purifies the mercantile air.” Lewis retired in 1849, insisting that bankrupt brother Arthur, by then working for a nephew, replace him. In 1854, Arthur sold his interest to Benjamin Douglass, who in 1859 sold the business to Robert Graham Dun. The outfit thrives today as Dun & Bradstreet Inc.

Privately, the Tappan brothers continued their antislavery work, and prepared to violate the Fugitive Slave Law. Lewis Tappan, who had moved to Brooklyn Heights, occasionally helped Black leaders including the Rev. Amos Freeman hide and transport fugitives on the Underground Railroad. Arthur stabled a horse near the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania for fugitives’ use.

By the late 1850s, overshadowed by a younger generation of radical abolitionists, the Tappans mostly were supporting Christian missions to Blacks in the West Indies. Lewis got Arthur out of several financial jams. Arthur died July 23, 1865, at age 79. Lewis, who spent his last years writing an admiring biography of his brother, died June 21, 1873, at his Brooklyn home. He was 85. His funeral took place at Henry Ward Beecher’s Plymouth Congregational Church. Beecher spoke but the service was conducted by Amos Freeman, Lewis Tappan’s Underground Railroad compatriot. —American History senior editor Nancy Tappan is a distant cousin of Arthur and Lewis Tappan.